Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

The gallbladder (GB) is a pear shaped musculomembranous structure, lying along the hepatic undersurface, functioning as a reservoir to accumulate bile (~30–50 mL).

- ◼

Embryologically, the GB develops from a diverticulum outpouching in the caudal portion of the hepatic duct, becoming part of a continuous lumen within 3 months of gestation.

- ◼

The adult GB spans 7 to 10 cm in length and 3 to 4 cm in transverse diameter. It is located in the GB fossa, along the inferior hepatic surface, aligned with the interlobar fissure.

- ◼

Macroscopically, the GB contains the fundus, body, infundibulum and neck.

- ◼

The neck communicates with the cystic duct, which is most commonly lying to the right of the porta hepatis. The fundus often projects inferior to the right hepatic margin.

- ◼

Microscopically, the GB wall comprises the serosa (visceral peritoneum, covering the inferior aspect of the GB’s free surfaces), outer muscularis propria layer, lamina propria and inner mucosa (single cell layer).

- ◼

No submucosal or muscularis mucosal layers.

- ◼

Outer mucosal layer consists of dense fibrotic tissue, combined with randomly-oriented smooth muscle fibers.

- ◼

Inner mucosal layer consists of a single-layer of epithelial cells, rich vascular supply, but without lymphatic channels.

- ◼

Only the GB neck’s inner mucosal single cell layer secretes mucus and may contain neuroendocrine cells.

- ◼

The mucosal layer may contain deep diverticular outpouchings (Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses), culprit structures in adenomyomatosis, a risk factor in formation of black pigment gallstones.

- ◼

- ◼

The predominant GB blood supply is via the cystic artery and vein and some branches of the right portal vein.

- ◼

Primary lymphatic drainage is via cholecystoretropancreatic, and to a lesser extent, via the cholecystoceliac and cholecystomesenteric nodal roots.

- ◼

Some anatomic variants include the GB fold (such as a Phrygian cap), GB septation (acquired or congenital), Hartmann pouch/infundibulum, accessory GB and agenesis.

- ◼

Cholecystitis (CS) refers to GB inflammation and has various presentations, ranging from acute acalculous/calculous to chronic, emphysematous, suppurative and xanthogranulomatous CS.

- ◼

Acute calculous cholecystitis (90%–95%): Develops as a result of gallstone obstruction of the GB neck/cystic duct, resulting in bile salts-induced chemical irritation of the GB mucosa, increased GB luminal pressure/distension, GB wall thickening (because of restricted blood perfusion), with progressive GB wall edema and inflammation

- ◼

Perforation is present in 3% to 10% of cases.

- ◼

Emphysematous cholecystitis is a rare complication.

- ◼

Superimposed bacterial infection in nearly two-thirds of cases.

- ◼

- ◼

Acute acalculous cholecystitis (2%–12%): Develops often in critically ill patients, in the absence of gallstones or without their contribution. It occurs secondary to biliary stasis ±GB ischemia. Rarely, it may occur as a result of metastatic disease to the GB.

- ◼

Emphysematous cholecystitis: Rare subtype of acute CS, with GB wall necrosis resulting in GB wall/luminal gas formation.

- ◼

Most commonly in diabetics and male patients (typically 50–70 years old).

- ◼

Cystic artery vascular compromise plays a crucial role in its pathophysiology.

- ◼

Commonly isolated organisms include Clostridium welchii / perfringens , Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis.

- ◼

Surgical emergency because of the high risk of gangrene, perforation, and mortality.

- ◼

- ◼

Suppurative cholecystitis: Pus filled inflamed GB, more common in diabetic and vasculopathic patients, with gallstone (or rarely an underlying mass, such as cholangiocarcinoma) obstruction of the GB neck, subsequent infection/pus formation. Similar clinical presentation to acute calculous cholecystitis.

- ◼

Chronic cholecystitis: Chronic inflammation of the GB, nearly almost in the setting of intermittent cystic duct/infundibular obstructing cholelithiasis (95%) or GB dysmotility.

- ◼

The most common form of GB disease, referred to as low grade GB inflammation.

- ◼

Long standing chronic CS may result in mural calcification/porcelain GB.

- ◼

Possible histological correlation between chronic CS with Helicobacter pylori.

- ◼

Strongly associated with GB cancer, with incidence ranging from 12% to 61%.

- ◼

Prophylactic cholecystectomy in porcelain GB.

- ◼

- ◼

- ◼

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC): Chronic GB inflammatory disease, characterized with intramural ill-defined soft tissue nodularity and GB wall thickening.

- ◼

GB soft tissue thickening (90% of cases diffuse and 10% focal) may infiltrate into the liver (45% of cases), pericholecystic fat (45%–54% of the cases) and the adjacent bowel. Biliary obstruction and lymphadenopathy present in one-third of cases.

- ◼

Histologic constituents are wax-like ceroid xanthogranuloma, with foam histiocytes, lymphocytes, fibroblast and multinucleated giant cells.

- ◼

Possibly arising from the rupture of occluded Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses.

- ◼

Uncertain relationship with gallbladder carcinoma.

- ◼

- ◼

Gallstones occur in 10% of the population, however more commonly in Caucasians, females, middle age, obese individuals, and those with a family history of stones.

- ◼

Gallstone types include cholesterol, mixed (most common), and pigment stones.

Techniques

Ultrasound

- ◼

Ultrasound (US) is the preferred initial diagnostic modality to assess for acute biliary/GB pathology.

- ◼

US has a sensitivity of 48% to 100% and specificity of 64% to 100% for acute cholecystitis.

- ◼

Normal GB is an oval, echo-free structure.

- ◼

An US landmark is an echogenic line from right portal vein bifurcation to GB.

- ◼

- ◼

US is highly sensitive and specific for gallstone detection.

- ◼

Diagnostic criteria for gallstone: Echogenic intraluminal foci and acoustic shadowing in two views (longitudinal and transverse).

- ◼

- ◼

In acute cholecystitis:

- ◼

Sonographic signs include presence of gallstones, gallbladder wall thickening (>3 mm), GB wall edema, GB distension (>40 mm in short-axis and >80 mm in long axis), positive sonographic Murphy’s sign, pericholecystic fluid ( Fig. 18.1 ).

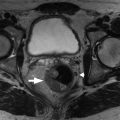

Fig. 18.1

A and B, Sagittal ultrasound in a 29-year-old woman with a distended gallbladder, slight wall thickening, and intramural gallbladder lucencies ( long arrow ) caused by acute cholecystitis. There is an impacted stone at the gallbladder neck ( short arrow ). The patient had a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign.

(From Boland GW. Gastrointestinal Imaging: the Requisites , ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2014.)

- ◼

Presence of gallstones is the most common and sensitive sign of acute calculous CS, particularly in conjunction with visualization of obstructing cystic duct/GB neck stones.

- ◼

Sonographic Murphy’s sign refers to maximal tenderness elicited by transducer pressure over the GB during inspiration (~92% sensitivity in acute CS).

- ◼

Pericholecystic fluid and inflammation are secondary signs.

- ◼

- ◼

In acute acalculous cholecystitis:

- ◼

Imaging features are similar to calculous cholecystitis, except for the absence/contribution of gallstones and presence of GB sludge ( Fig. 18.2 ).

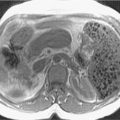

Fig. 18.2

Acute acalculus cholecystitis. Sagittal ultrasound image in a 45-year-old woman with sepsis shows distended gallbladder filled with echogenic sludge and diffuse wall thickening. No calculus was identified on the scan.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

- ◼

In gangrenous CS:

- ◼

US features are asymmetric GB wall thickening ± sloughed off intraluminal membranes.

- ◼

Sonographic Murphy’s sign is negative in 66% of the cases because of denervation.

- ◼

- ◼

In emphysematous cholecystitis:

- ◼

US features include “dirty-shadowing” from the reverberation artifact of the gas locules, particularly in the dependent portions.

- ◼

- ◼

In XGC:

- ◼

US is of limited diagnostic utility because of suboptimal evaluation of adjacent organ extension, evaluation of the extent of surrounding inflammation and distinguishing it from GB malignancy.

- ◼

Nuclear medicine

- ◼

In acute cholecystitis:

- ◼

Biliary scintigraphy is the gold standard for acute cholecystitis, particularly secondary to cystic duct obstruction, using technetium-99m (Tc99m)-diisopropyl iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan.

- ◼

HIDA is 86% to 100% sensitive and 94% to 100% specific with a diagnostic accuracy of around 92%.

- ◼

HIDA scan diagnostic criteria include GB nonvisualization at 3 to 4 hours postradiotracer administration (or 30 minutes after morphine sulfate augmentation).

- ◼

False negative can occur with partial filling of the GB within 60 minutes of radiotracer administration and can be reduced by morphine administration.

- ◼

False positives, with GB nonfilling, may occur without obstruction in fasting patients with severe hepatic disease or total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

- ◼

- ◼

Limited information on nonobstructing cholelithiasis.

- ◼

In acute emphysematous cholecystitis, there is nonvisualization of the GB with a rim of increased hepatic activity around the GB fossa (“rim sign”) .

- ◼

- ◼

In chronic cholecystitis:

- ◼

Hepatobiliary scan is normal in 28% to 90%, particularly if asymptomatic.

- ◼

Stasis of concentrated thick bile, particularly in the cystic duct, may preclude GB visualization in symptomatic patients, resulting in a positive scan.

- ◼

Visualization of bowel activity before GB visualization during the first hour is suggestive of chronic cholecystitis.

- ◼

Overall accuracy of around 73%, but diminished with severe hepatic disease, TPN or in fasting states.

- ◼

In XGC: HIDA does not allow for a specific diagnosis.

- ◼

Computed tomography

- ◼

In acute calculus cholecystitis:

- ◼

Computed tomography (CT) confers an accuracy of around 94%, however at the cost of ionizing radiation.

- ◼

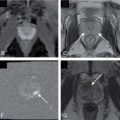

Most common CT findings are GB wall thickening and presence of gallstones ( Fig. 18.3 ).

- ◼

Gallstones are seen in 75% of cases.

- ◼

20% to 25% of gallstones are isoattenuating to bile on CT, therefore missed.

- ◼

- ◼