Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) can be intermittent, periodic, or constant with fluctuating levels of severity. Nearly 15% of all menstruating women experience some form of CPP. A large number, almost 60% of all women with CPP, go undiagnosed, and another 20% never undergo imaging investigations into the etiology of their pain, with only 50% completely cured with treatment. The differential diagnosis of CPP is extensive and includes abnormalities of the uterus and endometrium, the ovaries, bladder, vascular structures, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, peritoneum, and iatrogenic conditions such as fistulae and retained foreign bodies. Imaging can be helpful in directing the physician to the organ of interest and determining therapy.

Disease

Definition

CPP is defined as nonmalignant pain perceived below the level of the umbilicus, which is constant or recurring over a period of 6 months or more. CPP, in some cases, causes sufficient physical or psychologic suffering or impairment to adversely affect quality of life. Pain related to pregnancy, malignancy, menstruation, and sexual intercourse is typically excluded from the CPP diagnosis.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

CPP affects women of all ages; however, most often patients tend to be slightly younger than the general population, averaging 27 to 29 years of age. The average duration of symptoms reported by women with CPP is 2.5 years. There is no significant correlation with mean gravidity and parity, rates of elective abortion, racial distribution, or mean educational attainment. Prevalence ranges in different studies from 4% to 25%. In their article, Mathias et al. polled more than 5000 women and suggested a prevalence rate of 14.7% for CPP.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

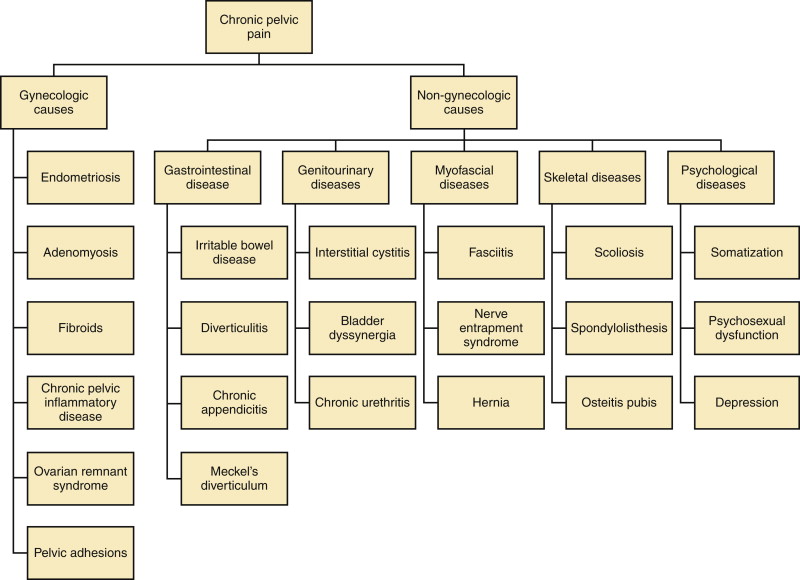

CPP is a multifactorial condition with possible sources of pain in the genitourinary, GI, skeletal, and myofascial structures as described in Figure 11-1 . In a large primary care database from the United Kingdom it was found that GI disorders were a common cause of CPP (37%), followed by urologic (31%) and gynecologic disorders (20%). Myofascial disorders contributed an additional 12%, with endometriosis accounting for approximately 30% of pain from this cause. Usually more than one contributing factor, however, is found in an individual patient.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients usually present with a history of pelvic or lower abdominal pain lasting for longer than 6 months. The patient with CPP requires a complex detailed clinical assessment that demands significantly more time than the average patient consultation. A multisystem approach is essential for assessing the cause(s) of CPP. The history should include its quality, location, radiations, duration, severity, aggravating and relieving factors, relation to menstrual cycle, bowel and urinary functions, physical activity, and impact on daily functions.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

The choice of an imaging study to assess CPP patients should depend on the clinical suspicion of a specific etiology after a thorough clinical assessment has been performed. In case gynecologic causes of CPP are suspected (i.e., uterus, tubes, and ovaries), ultrasound (US) is considered the imaging modality of choice for initial assessment. If US is negative, however, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) can provide important additional information. For the diagnosis of nongynecologic causes of CPP, US is less useful, and the preferred examination could be CT or MRI depending on the condition suspected. Consequently US is more sensitive for detecting endometriosis that has extended to the uterus and ovaries compared with use in women who only have peritoneal implants and adhesions, for which MRI performs better.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Radiography

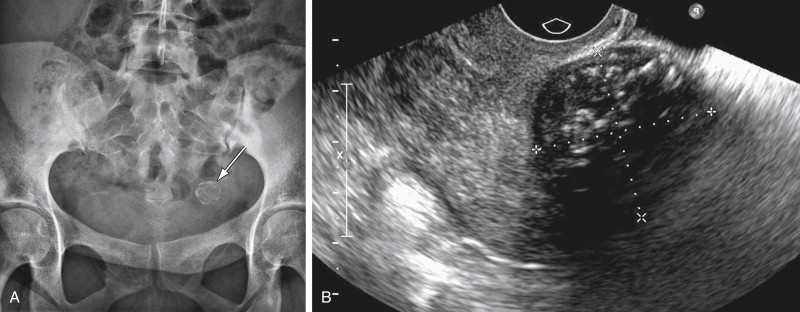

Even considering some advantages like the low cost and low radiation dose, plain films have little role in the assessment of CPP. Nevertheless, some pathologies like urinary tract stones or calcified fibroids can be identified using plain films ( Figure 11-2 ). Radiography may prove useful when bony abnormalities are suspected.

Ultrasound

The advantages of US compared with other imaging methods include no use of radiation or intravenous contrast and lower cost compared with CT and MRI. Many of the abnormalities described below are considered in more detail in other chapters. We will review these abnormalities as they related to CPP.

Gynecologic Causes

US is particularly helpful in identifying gynecologic causes of CPP. Suprapubic (transabdominal) US is a valuable tool to obtain a general overview of the pelvis, but transvaginal US (TVUS) is essential to obtain the resolution necessary for accurate gynecologic diagnosis. One important advantage of endovaginal US over other imaging modalities is the possibility of applying pressure over a specific organ during the examination; this maneuver can elicit the same symptoms that are being investigated, confirming this way the origin of the problem.

Fibroids

Fibroids can cause pelvic pressure symptoms from compression of surrounding structures if fibroids are large. Rarely acute pain is seen in fibroids as a result of complications like infarction, torsion, or expulsion through the cervix. Fibroids, although common, are considered a rare cause of CPP and mostly correspond to a nonrelated incidental finding. The uterine contour may be smooth or lobulated, and the endometrial echo may be distorted depending on the location of the fibroid. US can differentiate between submucosal, intramural, broad-based subserosal, and pedunculated fibroids. Large intramural and subserosal fibroids can cause mass effect on adjacent organs with the corresponding symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, constipation, and pelvic pain. Pedunculated (submucosal or subserosal) fibroids can cause acute pain if they undergo torsion, and submucosal fibroids can cause abnormal bleeding. Fibroids have a heterogenous internal echotexture ( Figure 11-3 ) on US and may cause acoustic shadowing. The acoustic shadowing may occur from areas of calcification, from the interface between the margins of the fibroid and adjacent myometrium, or from the edges of smooth muscle whorls within the fibroid as described by Kliewer et al.

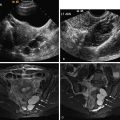

Endometriosis

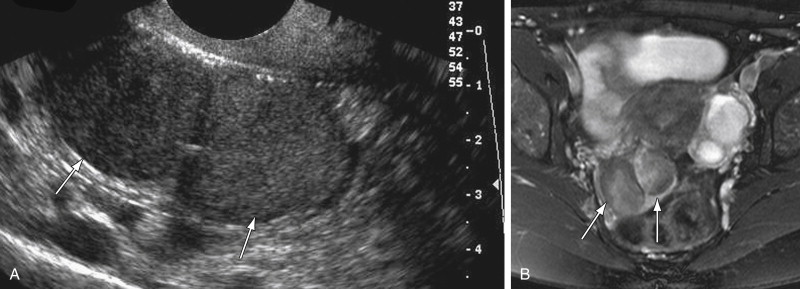

US has a high sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 98% for diagnosis of ovarian endometriomas; however, diagnosis of endometrial implants elsewhere in the abdomen and pelvis is limited on US. These ectopic implants hemorrhage with the menstrual cycle and cause pelvic pain and cramping. Classic endometriomas typically show presence of low-level homogeneous internal echoes in 95% of cases ( Figure 11-4 ). In some unusual instances they may be anechoic, mimicking a functional cyst. They may be unilocular or multilocular and may have septations; infrequently they may have irregular wall thickening, wall nodularity, and echogenic foci within the cyst wall. Other sites of involvement by endometriosis include uterosacral ligaments, ovaries, peritoneum, bladder, mesentery, and the GI tract, in decreasing order of frequency. MRI is more sensitive than US for diagnosis of extraovarian implants of endometriosis.

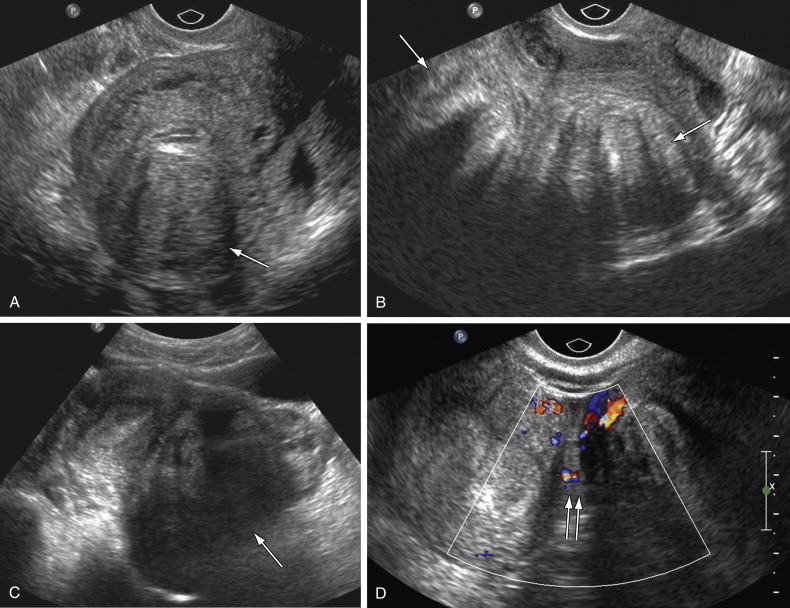

Adenomyosis

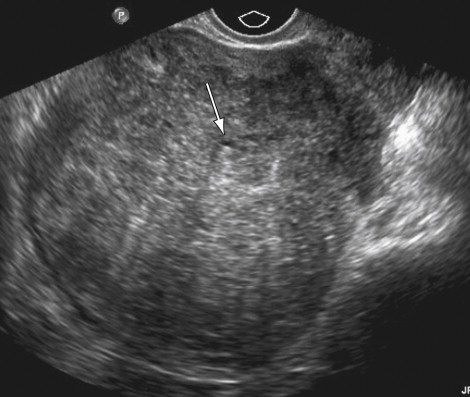

US has a sensitivity of 80% to 86% and a specificity of 50% to 96% for diagnosis of adenomyosis. Common findings on TVUS include poorly demarcated hypoechoic areas in the myometrium with or without small cysts, and thickening of the anterior or posterior myometrium ( Figure 11-5 ). On color Doppler, in contrast to fibroids in which vessels are located in the circumference of the fibroid, in adenomyosis the blood vessels follow their normal straight course in the myometrial areas.

Chronic Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

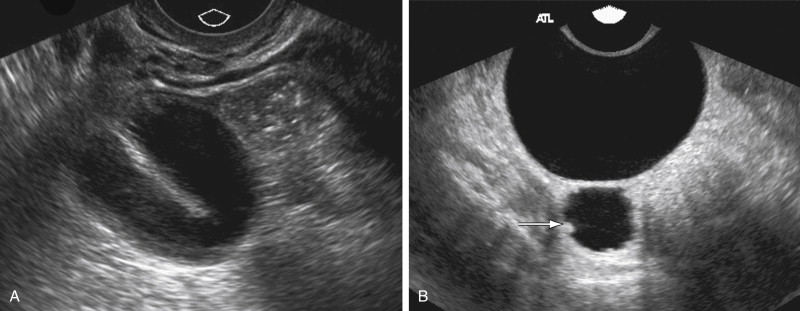

In chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) the acute inflammation subsides, but if the tubes are occluded, they can give rise to hydrosalpinx. US findings of a hydrosalpinx include a dilated fluid-filled tubular structure that is often convoluted in appearance and may have a “cogwheel” appearance or the “beads-of-string” sign as a result of thickened endosalpingeal folds. The dilated fallopian tube folds on itself to form a sausage-like C- or S-shaped cystic mass ( Figure 11-6 ). US has a high sensitivity of 86%, specificity of 98%, and accuracy of 98% for diagnosis of hydrosalpinx.

Pelvic adhesions can be related to CPP, although it is not clear whether they can cause it per se or are merely a manifestation of other processes like endometriosis and PID. Specific indicators of pelvic fibrosis or the “frozen pelvis” have not been described on US. The “freely mobile” pelvis, however, was defined by Okaro et al. as free gliding of the ovary over the internal iliac vessels when gentle pressure was applied; fixed position of one or both ovaries was defined as lack of free movement of the ovary. In their series, none of the normal patients had nonmobile ovaries compared with the patients with pelvic adhesions.

Nongynecologic Causes

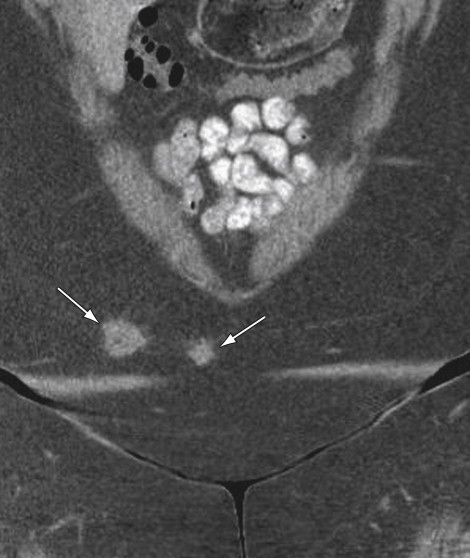

Vascular

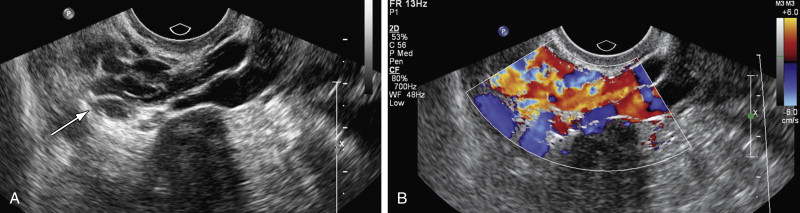

Pelvic congestion syndrome is seen in patients with CPP and ovarian point tenderness on physical examination. Most of these patients are multiparous and on imaging have ovarian and pelvic varicosities. This entity is controversial as a cause of pelvic pain because many individuals have varicosities in their ovarian or parametrial veins and do not have CPP. In a study on asymptomatic renal donors, 48% presented ovarian vein varicosities ; some authors report 68% to 75% of patients with congestive pelvic syndrome experience improvement in their symptoms after ovarian vein embolization procedure, but these studies did not have a control group. With transabdominal US (TAUS) examination it is possible to identify the left ovarian veins and measure the diameter, although this can be technically challenging, particularly in obese patients. Some authors suggest a left ovarian vein measurement cutoff of 6 mm or more with a positive predictive value of 83.3%. Color Doppler can show large parametrial ( Figure 11-7 ) and myometrial varices, and spectral Doppler assessment can show reverse flow in the left ovarian vein. All these findings are not specific and can be seen in asymptomatic patients; therefore the diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome should combine clinical and radiologic findings and exclude other potential causes of CPP.

Urologic

One of the most common urologic causes of CPP is interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome. Images play no role in the diagnosis of this entity except for ruling out other problems that can present similar symptoms. Bladder carcinoma in situ can cause only irritative voiding symptoms, but chronic pain is most likely related to advanced tumors invading other pelvic structures. US can confirm the presence of a mass, but it is limited for staging. CT and MRI are the preferred modalities.

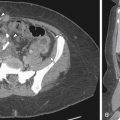

Urethral diverticula are a rare cause of CPP. It may not be suspected clinically, thus causing delay in the diagnosis of this entity. Only 50% to 60% of the cases have a detectable urethral mass on physical examination; therefore medical imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis. A good quality sonographic assessment of the urethra can be done with translabial or endovaginal US, although it is necessary for the radiologist to build up experience for this rare examination ( Figure 11-8 ).

Other Nongynecologic Causes

In general US has a very limited role in GI, musculoskeletal, and neurologic causes of CPP. When there is a possible involvement of these systems, CT and MRI are the modalities of choice.

Computed Tomography

CT provides a more limited assessment of the uterus and ovaries compared with the superior tissue resolution of US and MRI, but it is extremely valuable assessing extragynecologic pelvic organs like the bowel, urinary system, lymph nodes, and vasculature. CT is also better if upper abdominal organ assessment is necessary, as in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or cancer staging. Within the limitations of CT are elevated cost, use of radiation, and the frequent need for intravenous contrast.

Gynecologic Causes

Fibroids

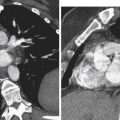

CT findings in fibroids will depend on the presence of intravenous contrast, size and location of fibroids, and degree of degeneration. The fibroid uterus is enlarged with lobulated contour and heterogenous attenuation ( Figure 11-9 ). The presence of coarse calcifications may help to suggest pathology to be of uterine origin; however, these findings are nonspecific.

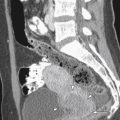

Endometriosis

Endometriomas may appear solid, cystic, or mixed solid and cystic, resulting in an overlap in the appearances with an abscess, functional ovarian cyst, or even a malignant lesion. Because of the poor specificity and high radiation dose, use of CT in the evaluation of pelvic endometriosis has been replaced by MRI. CT, however, would be helpful in detection of unusual areas of implantation of endometriosis, for example, in the abdominal wall ( Figure 11-10 ) or appendix or serosal surface of the urinary bladder, ureters, and fallopian tubes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree