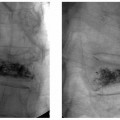

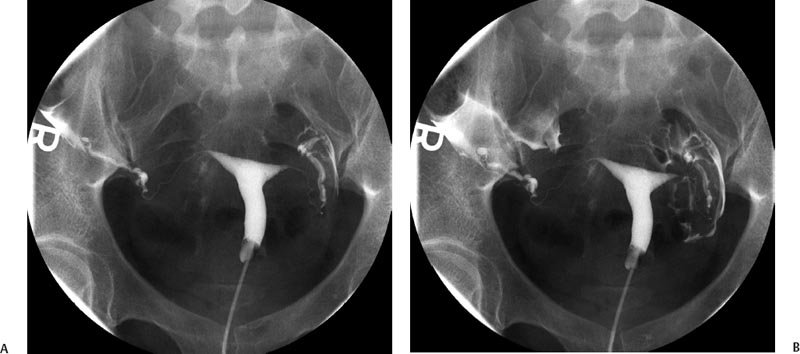

11 Clinical Review: Infertility Stephen Cohen Preservation of the species is the most basic instinct of every animal species. The ability to have offspring is desired by most of the population. Unfortunately, many couples are unable to conceive. Infertility has been defined as the inability to become pregnant after a year of attempting conception.1 It is estimated that 10 to 15% of reproductive age couples in the United States are infertile.2 The incidence of infertility rises significantly as a woman ages, rising to 35% when she is 40 years old. Her eggs become more resistant to fertilization and the incidence of chromosome anomalies increases, raising the likelihood of early pregnancy loss. The treatment of infertility is relatively unique in medicine because the practitioner is treating two patients together. During the last two decades, significant progress has been made in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infertility. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine has been conducting a campaign to inform patients of preventable causes of infertility and describes ways to lower that risk. Research has provided evidence-based data that has better defined the clinical tests and treatments most likely to help infertile couples. Certain tests that were performed in the past have been abandoned, while new tests have been discovered. There have also been significant improvements in diagnostic imaging, which have allowed practitioners to better diagnose and understand the clinical condition of the patient. Improvements in technology, pharmaceuticals, and imaging have revolutionized infertility treatments. New advances in surgical instrumentation allow the surgeon to use less invasive techniques and obtain better results. Medical therapy has improved our ability to treat ovulatory dysfunction and endometriosis. Advanced ultrasound imaging, in particular, has improved success rates with in vitro fertilization and intrauterine inseminations. Traditionally, the infertility workup consists of a comprehensive multiple system evaluation of the many complex processes of reproduction that must be performed precisely so that conception will occur. Areas of study include semen viability, cervical mucus, the endometrial cavity, the uterus, the fallopian tubes, the ovaries, and the peritoneal cavity. A basic infertility workup usually takes 2 to 3 months. Often more than one problem is discovered. The most common cause of female infertility is problems with ovulation. Ovulatory dysfunction is found in ~15 to 20% of all infertile couples and accounts for up to 40% of infertility in women.3 Ovulatory dysfunction can be classified as anovulation (absent ovulation) or oligoovulation (infrequent ovulation defined as less than 8 periods/year or cycles that are longer than 35 days), which can cause either gross or subtle menstrual disturbances.4 There are many causes for ovulatory dysfunction including elevated androgens, polycystic ovary syndrome, thyroid disease, elevated prolactin, low body fat (due to eating disorders, extreme weight loss, extreme exercise, etc.), obesity, Cushing syndrome, and chronic medical problems. Polycystic ovary syndrome is one of the most common endocrine disorders in women of reproductive age and the most frequent cause of oligoovulation or anovulation.5 Ovulation induction with clomiphene citrate or gonadotropins can be effective for these patients.5 A standard infertility laboratory evaluation will be diagnostic in most of these conditions. This includes obtaining progesterone, urinary luteinizing hormone (LH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), prolactin, and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels.4 Basal body temperature charting is a simple way to document ovulation; a rise in temperature is generally noted 2 days after a surge in LH occurs.6 Women older than 35 years of age may benefit from testing FSH levels on day 3 of the menstrual cycle to assess ovarian reserve.7 Stimulation and suppression tests can be added when clinically appropriate. If a specific condition is discovered, directed treatment, such as administration of exogenous hormones, will often be successful at restoring ovulation. Similarly, evaluation of a patient with ovulatory dysfunction may lead a practitioner to recommend oocyte donation.4 In patients who are anovulatory without a medical problem that can be specifically addressed, ovulation induction is the recommended treatment. This can be achieved by administration of exogenous gonadotropins or by augmenting endogenous FSH with clomiphene citrate.8 This drug blocks the negative estrogen feedback on the hypothalamus. Clomiphene is given once a day for 5 days shortly after a period to stimulate ovulation. The cycle can be monitored with ultrasound to evaluate the effects of the dose chosen. The information that ultrasound provides helps to fine-tune the timing and dose of clomiphene prescribed. The follicle size seen with this drug is usually slightly larger (22 to 24 mm) than those seen with spontaneous ovulation (20 mm). Clomiphene often produces two dominant follicles and so the twinning rate is increased in these patients (~25%). Adding the drug human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) to create a timed ovulation is particularly useful in patients who need intrauterine inseminations. When unmonitored clomiphene cycles fail to produce a pregnancy, more aggressive intervention can improve the pregnancy rate. Ultrasound is the critical part of this more aggressive approach. The leading ovarian follicle is followed with ultrasound beginning approximately 2 days prior to the expected ovulation, usually day 12. When the follicle reaches a size of 18 to 20 mm, an injection of HCG, which acts like LH, is given. Ovulation will occur 36 to 44 hours later. Eighty percent of appropriately selected patients will ovulate with this treatment.6 Aromatase-inhibitors, such as letrozole, may have the potential to replace clomiphene as an ovulation-inducing drug.8 Certain ovarian cysts decrease the fertility of women. Although any cyst may create infertility, an endometrioma is most likely to cause this problem. Disruption of ovarian function and ovum pickup are created by an endometrioma. In addition, severe pelvic adhesions involving the ovary, fallopian tube, and cul-de-sac are often associated with this type of cyst. The diagnosis of an endometrioma is confirmed via laparoscopy, but the condition is often first suggested by the pelvic ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 11.1). Not only is the ovarian cyst revealed, but these imaging modalities can usually demonstrate the unique characteristics of an endometrioma. Treatment of the benign ovarian cyst, regardless of the etiology, is surgical excision and in these cases, a cystectomy or oophorectomy will need to be performed. Depending on the pathology and condition of the patient, this surgery is either performed via operative laparoscopy or laparotomy. Fallopian tube disease can account for up to 25 to 35% of all infertility cases.9 The fallopian tube is an extremely complex organ that performs a vast array of physiologic processes, including ovum pickup, ovum transport, sperm transport, environmental support for the early embryo, and deposition of the embryo into the uterus. Even subtle changes of the fallopian tubal mucosa, such as those seen with ciliary immotility, can disrupt these complex processes. Any bacterial infection that can ascend into the fallopian tube might create structural damage which can inhibit the function of this fragile organ. The entire mucosal surface can be damaged by these infections. The most common infection creating tubal damage is Chlamydia, although many other bacteria can also damage the tube. The two areas of the tube that are most susceptible to an ascending infection are the intramural tube and the fimbrial portion. In the most severe situation, the infection creates a complete obstruction of the tube. An obstructed fallopian tube can therefore be due to an infection, can occur due to intraabdominal or pelvic surgery, or can be attributed to salpingitis isthmica nodosa or peritubal adhesions.9 Many patients with fallopian tube disease will require either tubal reconstructive surgery or in vitro fertilization.10 Fig. 11.1 Longitudinal ultrasound image of the left ovary in a 37-year-old patient with infertility. This image reveals a largely anechoic cyst within the left ovary that contains multiple internal echoes. On laparoscopy, this was found to represent an endometrioma. Fig. 11.2 (A) Early and (B) late view from a hysterosalpingogram in a 29-year-old patient with infertility. These images reveal a normal endometrial cavity and bilateral fallopian tube patency. The diagnosis of tubal damage or obstruction in an infertile woman is made initially by the hysterosalpingogram. During this procedure, water soluble contrast is administered into the endometrial cavity via a catheter or cannula. As the contrast is slowly infused, fluoroscopic monitoring enables the practitioner to demonstrate whether the fallopian tubes are patent by directly visualizing them and by demonstrating free spill of contrast into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 11.2). During the initial slow filling of the tube, mucosal folds should be demonstrated. Alterations or absence of these folds implies prior tubal infection. If contrast enters the fallopian tube but free spill into the peritoneal cavity cannot be demonstrated, then distal tubal disease can be diagnosed. A large collection of contrast at the distal end of the tube, occurring with a gentle infusion, is indicative of a hydrosalpinx, which is important to diagnose in an infertile patient. Recent studies have demonstrated that a hydrosalpinx decreases the pregnancy rate in women undergoing in vitro fertilization cycles. It is now recommended that a tube containing a hydrosalpinx be excised via laparoscopy prior to attempting in vitro fertilization. The practitioner performing the hysterosalpingogram must gently infuse the contrast into the uterus. Excessive pressure or volume can create an iatrogenic-produced hydrosalpinx. The distal fallopian tube may also be damaged by infections occurring from inflammation or perforation of a nearby organ, such as the appendix or colon. In these situations, the tube itself is usually not damaged, but surrounded by extensive adhesions limiting ovum pickup. Bilateral proximal tubal obstruction may be demonstrated on hysterosalpingogram during the infertility workup (Fig. 11.3

Ovarian Factors

Tubal Factors

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree