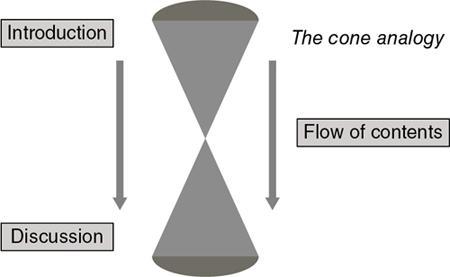

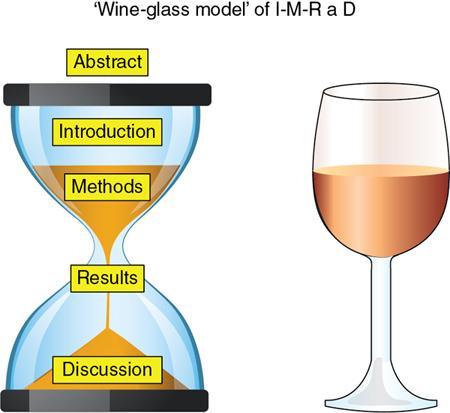

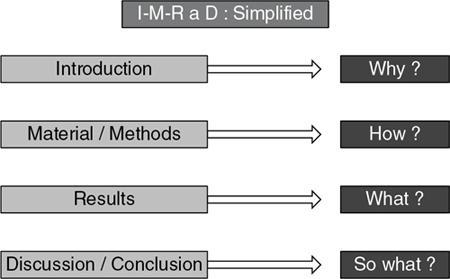

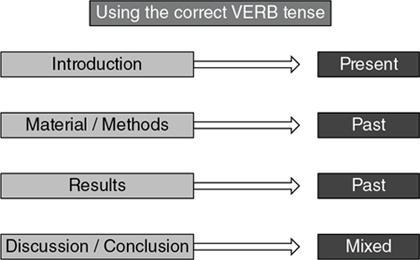

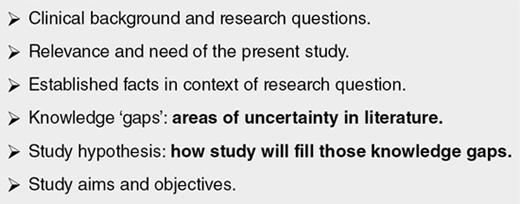

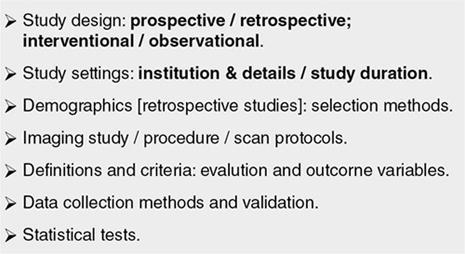

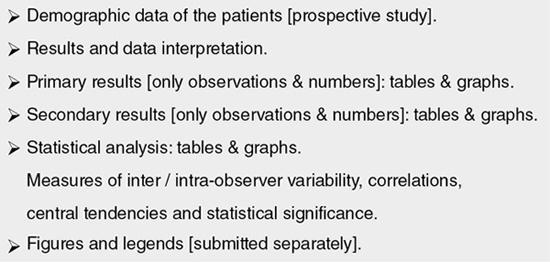

Nitin P. Ghonge, Nidhi Goyal, Binit Surekha, Abhinav Jain, Kriti Malhotra, Aishwarya Gulati Communication is a skill that you can learn. It is like riding a bicycle or typing. If you’re willing to work at it, you can rapidly improve the quality of every part of your life. Brian Tracy NITIN P. GHONGE & NIDHI GOYAL The journey to the frontiers of medical knowledge is truly endless. Since time immemorial, the unending zeal and continuous efforts of global medical researchers have always explored newer avenues in search for new medical knowledge. The innovative diagnostic and treatment methods were all devised and developed with the sole intention of better healthcare and to serve the humankind. “Medical manuscripts” are the essential keys to unlock the research-based new knowledge and are valuable tools for knowledge sharing in the scientific community. Manuscript writing is one of the most crucial components of a career in academic medicine and clinical Radiology is certainly not an exception. The digital revolution of the present times has an all-round impact on academics with use of computers, internet and digital tools in writing, editing and on-line submissions of scientific manuscript. The process of manuscript reviewing and editing in medical journals is now many times easier, faster and efficient with the use of technology. As the only thing constant in Medicine is “Change,” the medical knowledge is ever evolving with new updates on understanding of diseases, diagnostic techniques and treatment protocols coming on a continuous basis. Presentation of clinical observations and sharing of clinical data in conferences/CMEs and academic forums is an important event in medical community, which also applies to Radiology and Imaging sciences. It is, however, important to realize that less than 50% of these scientific presentations are converted and translated to scientific publications in peer-reviewed journals. Despite the greater academic significance of publications over presentations in the scientific arena, the reasons for this disparity are multifold. One of the key reasons include additional efforts to translate a presentation into publication and the lack of exposure to manuscript writing during post-graduate medical training in most of the countries. In Indian context, the situation is almost similar as the number of scientific publications in the indexed top-notch Radiology and non-Radiology journals is very low. Though there is no dearth of data and quality work in India, the number of high-quality publications is less and that too is confined to select academic centres. Moreover the number of abstracts presented at conferences/CME grossly exceeds the number of manuscripts that are published in the medical journals. At an individual level the likely causes may be inertia, shortage of time and lack of skills, guidance and motivation, while from broader perspective, this may be due to unfavorable infrastructure and work culture in Radiology departments and lack of post-graduate training in research methods. But “It is always better to light a candle than to curse the darkness.” There are few initiatives at institutional and association levels in India including workshops and symposiums on “Manuscript writing” and “Research methods” by Indian Radiology & Imaging Association [IRIA], which should be consolidated and further strengthened. An academic Radiologist is expected to conduct relevant “hypothesis-based” clinical research and share the validated results in the form of scientific publication for applications in routine clinical practice or to provide directions for future research. Manuscript writing is an inherent part of the research project. Scientific publication is the definite “end-point” for a particular research project. Publication of a scientific manuscript is the ultimate and most important component of clinical research in Radiology. Through publication of a scientific manuscript in Radiology, the stated observations and knowledge of the author becomes a citable science, which can be transmitted to clinical Radiologists and researchers across the globe for generations. Radiologists should learn and understand the science and art of writing manuscripts for a successful and productive academic career. Apart from Clinical Radiology, every Radiologist need to learn and understand the basic concepts about clinical research and bio-statistics including types of studies, data collection/analysis, graphical representation of results, parameters of test accuracy and their implications. Apart from presentation skills, Radiologist needs to know the nuances of publication process and learn the art of manuscript writing. Apart from enhancing the academic credentials of authors, a good scientific publication is expected to advance the science of Radiology, create a positive impact on healthcare and provide help to humankind. The secret to getting ahead is to getting started. One of the most important challenges for the beginner is to overcome the initial inertia and to find the appropriate motivation for manuscript writing. These motivational factors may include love for radiology, passion for medical education, zeal for better patient care, inclination for research, peer pressure, workplace incentives or their combinations. Irrespective of the precise motivating factors, it is important for an academic radiologist to clearly make up their mind to embark on academic path early in their career. Once the zeal and motivation is in place, priority and time will always follow. It is important to follow a balanced approach in an academic career. Based on the individual priorities and the workplace culture, a young Radiologist should adopt manuscript writing as an integral part of work and routine lifestyle. Young Radiologists should develop the habit of manuscript writing early in their careers. As there is never a wrong time to do the right thing, mid-career or senior Radiologists can also start manuscript writing with greater degree of zeal and determination to overcome the beginner’s inertia. The purpose of scientific writing is to communicate new knowledge or clinical observations in the form of a coherent, concise and logical document. The document shall form the basis for the expected clinical applications by medical fraternity or extrapolated clinical research by the research community. Scientific publication may provide avenues for future research for the advancement of scientific knowledge. Scientific manuscript in radiology should be therefore written in a precise manner, which should clearly communicate the required information with reference to current clinical practice and existing body of knowledge with potential clinical or research implications. “Scientific manuscripts should be essentially long enough to cover the area of interest and short enough to create and maintain the reader’s interest.” Scientific manuscript is one of the marks of human civilization. A published medical article is an indisputable evidence of research and is a structured document. Scientific manuscript has primarily five sections: abstract, introduction, material/methods, results, discussion and conclusion. Clinical implication carries vital importance and should convey a specific message to facilitate diagnosis or treatment either directly or indirectly. The objective should aim to provide solution to a specific clinical problem. Scientific publications are small “packs” of scientifically tested medical knowledge which is going to stay for generations and may impact the future of humankind. Thorough review of current literature is one of the important components of a good manuscript. Moreover, good manuscript should be free of any elements of ethical misconduct like falsification of data, plagiarism, redundant publication or inappropriate authorship. Always remember, “intellectual honesty” is the best policy while “writing” a scientific article. The scientific quality is the single most important consideration to decide the fate of manuscript after it is submitted to a journal for publication. The potential clinical implications and the incremental value to the scientific knowledge are the key requirements for a good manuscript. Clear and concise writing and correct grammar are important requirements. The manuscript should have structured contents, clarity of language and gradual flow of contents for the sake of easy readability and understanding. Even the manuscript with most complex topics should aim to offer easy readability for the reviewers and readers. Apart from the scientific quality of contents, a good manuscript stems from the art of writing, which plays an important role in deciding the fate of the manuscript. Radiologist needs to learn this art of writing early in their career. Manuscript writing should not be seen as a burden or additional workload. An academician should enjoy translating his/her research to a scientific publication in “black and white” with the intention of dissemination of scientific knowledge. It is very unlikely for a manuscript to be accepted in a journal without any revisions. The authors should be receptive to reviewer comments and constructive criticisms. Thoughtful and respectful responses to reviewer’s comments are keys to final acceptance of the manuscript for publication. At the outset it is important for the young radiology researchers to understand that scientific manuscript writing should be based on robust research and sound scientific methods of analysis. Scientific publications should be meaningful with clinical or research implications and should advance the science and serve the society. Publications certainly add value to one’s curriculum vitae, but that should not be the only objective. The purpose of publication should not be confined to the “numbers.” The quality of publications is more meaningful in terms of impact on healthcare. Less number of high-quality publications in high impact journals carries more credentials than large number of low/average quality publications in non-indexed or low-index journals. It is important for the young researchers to realize the actual purpose of publication and spend their time and energy in meaningful high-quality publications. They should not succumb to “predatory publishing” or exhaust themselves in the publication “rat race.” “Predatory publishing is an exploitive academic publishing business-model that involves charging publication fees to authors without checking articles for quality and legitimacy and without providing the other editorial and publishing services that legitimate academic journals provide, whether open-access or not”. Jeffrey Beall, a librarian and research at University of Colorado, Denver initially coined the term “Predatory Publishing” and warned the researchers about this unethical practice in select scientific journals. A study mentioned that 60% of the articles published in these journals receive no citations over the 5-year period following publication. Predatory publishers usually target the ambitious authors who are in search of appropriate journals for their manuscripts. With fancy journal names and impressive websites, these publishers send repeated email communications in flowery language to seek manuscript submission from the potential authors. They readily accept the manuscripts and expedite the publication processes in return for a publishing fee, without paying the required attention to the scientific contents and quality of the submitted manuscript. Radiology researchers should therefore refrain from being over-competitive in terms of number of publications and rather focus on the scientific quality and positive impact of the manuscript. “Publish or perish” is an appropriate aphorism to describe the intense pressure to publish in highly competitive academic environment in present times. Scientific publication should address the clinical problem and should be viewed as a potential solution to the clinical problem. They should serve the bigger purpose of filling the knowledge gaps, advancing the science and serving the humankind. Always, aim to “publish meaningfully with potential impact on healthcare.” It is important for the beginners to understand the editor’s thought process before writing and submission of the scientific manuscript. Most of the journal editors are full-time or part-time Radiologists, who handle the editorial responsibilities in addition to their busy clinical practices. With years of editorial responsibilities and hundreds of reviewer assignments, they are often able to perform a rapid screening of manuscripts to segregate the manuscripts which deserve further consideration from the large pool of manuscripts submitted to any standard journal. The rest of the manuscripts straight away face “rapid rejection” for one or the other reason. It is therefore crucial for the manuscript to survive the initial stage of “rapid rejection.” One of the effective ways to survive the stage of “rapid rejection” is to focus on hypothesis or relevance of the study and the discussion section of the manuscript. The introduction section should carefully describe “WHY” the study was performed. The study hypothesis or its relevance should be able to create interest in the mind of editor. The discussion section addresses the “SO WHAT” component of the scientific paper and therefore decides the incremental value of the manuscript in terms of filling the knowledge gaps and the advancement of the scientific knowledge. It is, however, important to understand that there are no short-cuts in manuscript writing and all major sections of manuscript are important from editor’s, reviewer’s and reader’s perspectives. Appropriate attention should be paid to all the major sections of manuscript including the images/legends, tables, references, statistical methods and the ethical aspects. Another effective way to learn and understand the nuances of scientific writing is to perform “manuscript reviews” for a scientific journal. Peer and editorial review process is an indispensable part of indexed bio-medical journals. The reviewer provides valuable information about a particular manuscript in terms of its scientific contents, clarity of communication and clinical/research implications. By virtue of their clinical knowledge, the reviewers are able to influence the journal’s editorial decisions in a significant way. Good reviewer should be particular about the quality of the reviews and should be able to provide rational reason for acceptance or rejection of a manuscript. They should be careful about the timeliness and ethical issues and should always respect the author’s efforts and expertise. Medical reviewers play an important role in the editorial process as the “gatekeepers” of medical knowledge. This is an immensely satisfying job for a person with academic inclination to simultaneously serve the science of medicine and to learn the art of scientific writing. Manuscript rejection may be a disappointing experience particularly for the young authors. Repeated rejections may discourage the authors from further submissions. The manuscript rejection rates for the high impact journals may be as high as 90%. It is important to realize that at least 50% of the rejected manuscripts are published elsewhere within 2 years of initial rejection. It is important for the authors to go through the reviewer comments carefully and incorporate the suggested changes before submitting to the same journal or elsewhere, depending upon the rejection letter. A study reported the relation between post-publication impact and the submission history of the manuscripts. The published papers with history of prior rejection found more citations than first-intent submissions. This emphasizes the point that not all rejected manuscripts are low quality and most of them may be accepted for publication elsewhere, if optimally revised. Biomedical journal often have space constraints for publishable articles. The scope of the journal and its readership significantly affect the editorial decisions. The target journal should be carefully chosen depending upon the manuscript contents. The peer-review process of manuscript reviewing in the scientific journals is not completely free of biases and has its own inherent problems. The peer-review process is, however, expected to improve the quality and scientific value of the papers published in biomedical journals. Manuscript writing, submission and revisions takes significant time and efforts, a published manuscript is an important parameter of academic productivity. A good timely revision and resubmission of an initially rejected manuscript often leads to publication. Reviewer comments and constructive criticisms during the peer review should be utilized to improve the manuscript in a significant manner, which can enhance its scientific value and impact. Several studies attempted to address the common reasons for manuscript rejection by biomedical journals, which include lack of the importance and relevance of the subject matter; lack of consistency between study design, results and conclusions; lack of originality; and inappropriate, questionable or flawed methodology. Few important guidelines for the authors were published by Radiology, based on the fate of Neuro-Radiology articles submitted to Radiology over a period of 2 years to reduce the chances of rejection. These include seeking guidance, if English is not the author’s primary language, paying due attention to manuscript format and layouts, inclusion of appropriate data elements, inclusion of statement regarding the clinical implications of the study and emphasis on correct study design. Appropriate data elements in the form of checklist should be submitted to convince the reviewer that the study was properly designed and executed. The following guidelines have been published to help the potential authors in designing and executing the research studies: the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD), the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Another important cause of manuscript rejection is the statistical errors. Levine et al have listed top 10 statistical errors in manuscripts submitted to Radiology journal. These mainly include problems with statistical methods, sample size, statistical power and tests for biases and variability of observers. It is suggested that authors should consult the statisticians at the earliest during the stage of study planning itself so that the data collection, analysis and compilation components of the study are perfect in terms of statistics. If major statistical errors are realized at a later stage, the corrections are usually not possible and manuscript rejection is inevitable. It is equally important for the academic Radiologist to know and understand the basic statistical concepts which will avoid manuscript rejection due to major statistical errors. An interesting study published in American Journal of Radiology [AJR] analyzed the manuscripts submitted to AJR over a 2-year period in terms of country of origin, manuscript type, decision of the editors and the reasons for rejection. The most common reason for rejection was “lack of new knowledge” which accounted for approx. 44%–76% of rejections. Errors in research methodology, data analysis and language are flaws that can be corrected to certain extent. Minor errors in manuscript formatting and style are correctable. Editors expect reviewers to assess the scientific merits and validity of the research, rather than identify the grammatical and typographical errors. Language problems are correctable and are usually not the main reason for rejection. The study mentioned that in countries like India, medical education and medical records are solely in English but many languages and dialects are spoken. The rejection rates of manuscripts from India are quite high which is possibly related to the effect of educational, cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds and heterogeneity. So the single most important reason for the rejection of the manuscript is the lack of new or useful knowledge. The manuscript based on a “copy-paste” research or which does not address a clinical problem and does not add to scientific knowledge in any manner is likely to be rejected, even if the manuscript is written and edited in best possible manner. A good and meaningful manuscript is based on good research. A good and meaningful research is based on the clinical problem or which aim to fill the knowledge gaps. The primary objective of a medical manuscript should be to fill the knowledge gaps as applicable to any particular aspect of medical practice. The enhancement of author’s credentials and reputation is the expected natural outcome of a good manuscript but cannot be the primary objective. A good and meaningful manuscript should therefore essentially address the knowledge gaps between the clinical problem and the existing solutions. The contents of a scientific manuscript are divided into standard sections or categories – abstract, introduction, material/methods, results, discussion and conclusion, as the standard organizational structure for a scientific research manuscript. The key sections of introduction, material/methods, results and discussion are described as “IMRAD”. This is not an arbitrary publication format but rather a direct reflection of the different steps in the process of scientific research. Long articles may need sub-headings or sub-sections to clarify their content. Other types of articles like case reports, reviews and editorials would require a different format. The IMRAD structure helps to standardize the format of research articles across the journals which facilitate literature review processes. Standardized manuscript formats help the editors, reviewers and readers to navigate articles more quickly to locate the specific contents within the manuscripts. The uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals and the detailed instructions for each section of the manuscript are issued by International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), previously called Vancouver guidelines. These guidelines (first published in 1978) were previously known as “Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals (URMs).” Subsequently, as the scope of ICMJE guidelines gradually expanded beyond the standardization of medical manuscript formats into editorial and publication processes, the document is now renamed as “Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals.” ICMJE developed these recommendations to review best practice and ethical standards in the conduct and reporting of research and other material published in medical journals, and to help authors, editors and others involved in peer review and biomedical publishing create and distribute accurate, clear, reproducible, unbiased medical journal articles. The recommendations may also provide useful insights into the medical editing and publishing process for the media, patients and their families, and general readers. The “cone analogy” of scientific manuscript is helpful to explain the flow of contents (Fig. 1.31.1). This emphasizes the point that contents of the manuscript should be more generalized in the beginning of the text and should gradually focus on the specific study objectives, material/methods and study results. Then, the discussion section should again gradually address the wider clinical problem and the potential implications of the study results for the general population. The manuscript should have seamless flow of contents from the broad introduction of the clinical problem to specific details about the study objectives, material/methods and results. Similarly, the subsequent manuscript should have seamless flow of contents from the focussed approach about the study objectives, material/methods and results to wider clinical/research implications with wider perspectives. The “Wine glass model” of scientific manuscripts reemphasizes this point (Fig. 1.31.2). The introduction section of the manuscript (corresponding with the wider flared part of wine glass) starts with a broad description of the wider clinical problem and gradually explains the relevance of the study in the clinical context. The last section of the introduction tapers down to the specific purpose and objectives of the study. The material/methods and results sections of the manuscript (corresponding with the narrow part of the wine glass) only focus over the study material/methods and results. The discussion section (corresponding with the wider lower part of wine glass) again adopts a broader approach and should discuss the study results in context of the existing literature with potential clinical/research implications. The information in different sections of the manuscript, as per the IMRAD format may be better understood in terms of clinical/research question or study hypothesis. The introduction section should specifically explain WHY the study was performed. Material/Methods section should mention HOW the study was performed. The results section should convey WHAT was found in the study. The discussion section should explain why the study results are important and essentially answer the SO WHAT question (Fig. 1.31.3). In the present era of computerized literature search, the “structured abstract” is now an important component of medical manuscripts. This has led some researchers to modify the IMRAD acronym to AIMRAD to give due emphasis to the abstract. Medical journals are now increasingly adopting the format with a statement about the study objectives in “Introduction” section and a separate section for “Conclusions.” This modification is called “IaMRDC” which stands for Introduction with aim, Materials/Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Scientific manuscripts should be structured and well-organized to convey the study subjects/methods and data and its interpretation in a clear and comprehensible manner. There may be minor variations in the manuscript format and style between different bio-journal and therefore “instruction of authors” for the specific journal should be referred while writing a medical manuscript. The appropriate journal for publication should be chosen at the early stage, so that the manuscript is tailored specifically for that journal in accordance with instruction to authors. The guidelines for authors may change with time and, hence, should be referred to at regular intervals. Depending upon the manuscript contents, the choice of journal predominantly depends on the scope and readership of the journal. The objective parameters of journal’s status including the impact factor should be checked on the journal’s website homepage while deciding the journal. The processing fees and the open access options should be clear before the submission of manuscript. The authors may decide the alternative options, in case manuscript is rejected from the journal where the manuscript is initially submitted. Radiologists may submit their manuscripts to Radiology or non-Radiology clinical journals depending upon the exact objectives, contents and message of the manuscript. Most Radiology manuscripts follow a definable blueprint which should be clearly understood. Kliewer MA has provided a “step-by-step” guide to publication for beginning investigator which Radiology researchers and authors should follow. The authors should not worry about being unoriginal as the scientific writing is expected to follow specific pattern and formats in contrast to creative writing. A busy reviewer and the readers would expect the specific information about the study at specific sections and would not bother to search all over the manuscript. It is equally important to ensure usage of correct grammar tense, while writing the medical manuscript (Fig. 1.31.4). The introduction section is always written in present tense as it aims to provide the current perspective. The materials/methods and the results are written in past tense as the study is already completed and the results are acquired in the past. The discussion section may use past, present or future tense depending upon the exact sub-section and the context. The subsequent section will describe the finer points about the different sections of the manuscript. The manuscript title gives the first impression about the manuscript, which certainly matters. It is estimated that an average reader dedicates less than 2 s to read the title. Most of the search engines use keywords to locate relevant articles. Good titles should use the appropriate “keywords” to improve the chances of finding the manuscript on internet using the standard search engines like PubMed. An impressive title can also influence the potential readers to click on the open/download/save button during the literature search. A succinct, direct and strong title for the manuscript is an important determinant of the number of downloads. The title should be as short as possible without compromising the clarity and should not use acronyms or abbreviations. The title should be able to provide a clue about the expected contents in minimum possible words. The Title should cover relevant characteristics of the study like patient population, disease diagnosis and/or imaging sign/technique. Two sentences combined with a colon may enhance the message. Two part titles are more effective in terms of effectiveness, clarity and brevity. “Self-Care during COVID-19 & beyond- Science, Lifestyle & Common sense” is an example where each word conveys the readers what they expect to find. Another example for a Radiology manuscript is “Prostatic Arterial Embolization versus Transurethral Resection of Prostate in benign prostatic hypertrophy- A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial.” Such titles may carry more words but are still more effective in communicating the expected contents. Relevant catchy phrases in the titles always help in seeking reader’s attention. An example is “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Clinical and Imaging Features of Vascular Compression Syndromes.” The Abstract is a brief summary of the manuscript and serves key functions. Abstract may be the only section editors may read for initial screening and decision whether the manuscript deserves a detailed external review. The potential readers may use abstract to decide whether or not to read the complete article. It can be free styled or structured as per the journal’s norm. A structured abstract is a distillation of the four major segments: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. The reader should be able to grasp the key objectives, major results and overall message of the paper by reading the abstract. Keywords are mentioned at the bottom of the Abstract section. These words [usually 4–8] denote the key points of the manuscript and help identify the manuscripts during the electronic literature search. The key words should be carefully chosen and should be based on the key contents of the study. The keywords need to be simple and specific to the manuscript and should be derived from the study title. The introduction section should provide the appropriate background information and the relevance of the study in context of the existing body of knowledge. The specific clinical problem and the existing solutions should be briefly discussed with reference to the major papers on the subject. The background information should not be very vague and should get to the specific point before the readers lose interest. The broad points which should be covered in the introduction section are mentioned in Fig. 1.31.5. The first paragraph may start with some of the words from the title and should provide the broader perspective about the clinical problem in brief. The magnitude and importance of the disease in question should be described. The second paragraph should provide a context and rationale/need for the current study. The relevant established facts and the areas with uncertainty in the context of the study question should be included. This paragraph discusses the knowledge gaps and offers justification and relevance for the study. The third paragraph should emphasize the exact reason why this study is important and is likely to fill the stated knowledge gaps in the field. The last sentence of this paragraph should essentially be a purpose statement and should be “The purpose of this study was to…..” If there is more than one aim for the study, specify the primary aim and address the secondary aims in a separate sentence. The reviewers and readers have a very strong and fixed expectation that the purpose of the study will be found in last sentence of the last paragraph of the introduction. Any word or name with standard abbreviation should be written in its expanded form as soon as it is mentioned for the first time, with the abbreviation in parenthesis. Subsequently, only the abbreviation should be used throughout the manuscript. It is important to avoid referring to papers using the author names unless and until a landmark study is being quoted. Such strings of proper names tend to slow the pace of the writing and affects readability. It is better to mention the relevant points about the study and reference it with a number at the end of the sentence. A common error while writing an introduction is an attempt to review the entire evidence available on the topic. Excessive background information in the introduction section is likely to obscure the purpose and importance of the study. The important points in the Introduction section need to be addressed in the Discussion section, and it is important to avoid repetitions. The introduction section sets the tone of the manuscript and should not constitute more than 10%–15% of the total manuscript. A good introduction section is expected to ignite reader’s interest and motivate them to read the complete article. Materials and Methods section is the link between the Introduction and Results sections. It describes the materials used and the methods followed to perform the study. The details should be clearly stated like a “cookbook,” such that other experts in the field could reproduce the experiments. This section may be divided into specific subsections to provide a clear organization. The broad points which should be covered in the Materials and Methods section are mentioned in Fig. 1.31.6. The first subheading should describe the study design and subjects. The study design – prospective or retrospective; interventional or observational; and cohort or randomized controlled or case–control study – should be clearly documented. It is then important to describe the institution/hospital details, study settings and time duration of the study. Subsequent paragraph should describe the study subjects and their characteristics (demographics) along with the patient selection methods and inclusion/exclusion criteria. The readers need to clearly understand the subject population, since extrapolation of results from one subject group to another may lead to selection bias. A flow chart is an effective way to convey the patient selection methods adopted in the study. The final study numbers and the numbers in each study group should be clearly communicated in the manuscript text as well as in the tables, as applicable. In a retrospective study, the patient demographics should be included here. The details about the institutional ethical board approval and informed consent should be stated. The second subheading should discuss the imaging study or procedure. The section should describe how the imaging data was acquired. The details about the imaging device, device manufacturer, imaging parameters, contrast media used and other relevant details should be mentioned. A table may be a useful format to communicate details of the imaging acquisition methods in few studies. The section should include the observer(s) details, who have performed the image interpretation or procedure in the study. Appropriate scan images may be included here to describe the measurement techniques stated in this section. The third subheading should clearly define all the study definitions and criteria used in the study. The interpretation methods used in an imaging study should be stated. No assumptions should be made and all relevant criteria should be defined so as to create a data which is valid, objective, reproducible and comparable. The standard units of measurements and the internationally accepted abbreviations should be used in the manuscript. The evaluation and outcome variables should be clearly defined in this section. The “gold standard” used in the study should be clearly defined. The fourth subheading should describe data collection methods and validation. The section should convince the reviewer and the readers about the fairness and robustness of the study data. The measures to minimize inter- and intra-observer biases and the blinding methods should be stated in this section. Several online guidelines are available to maintain uniformity in reporting the different types of studies such as Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for randomized controlled trials, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) for observational studies, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for systematic reviews and Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) for studies on diagnostic accuracy. It is important for the authors to adhere to these guidelines for the sake of clarity and completeness of the section on materials and methods. The final subheading should essentially convey the statistical tests used in the study. It is important for Radiologists to understand the basic concepts in biostatistics and to use the appropriate statistical tests for correct data interpretation. Standard text may be consulted for the practical applications of biostatistics in clinical studies. As various user-friendly software systems are now available, an increasing number of researchers are performing the statistical analysis of their own. Short, online certificate courses on biostatistics are available for the basic understanding of the key concepts. Biostatisticians are, however, still consulted for the statistical analysis. This should be done at the earliest during the stage of planning the study so that the data collection methods are appropriate. Lastly, describe how the quality of the results was evaluated. If applicable, determine both the reliability (precision) and validity (accuracy) of the acquired data. Interpreting diagnostic test results requires an understanding of key statistical concepts. Statistical tests should be discussed in the order in which they were applied to the data. Typically, the paragraph should start with descriptive statistics to describe the study population and then the specific statistical tests of association to describe the effects of the experiment or a comparison between populations should be stated. A statement about sample size and power calculations may be needed. The last sentence of this paragraph should include a statement of what P value represents an acceptable level of statistical significance. Traditionally, this value is .05, but if a different level is chosen (usually a more conservative one), then that should be stated and the reason given. The Results section should be written in accordance with the Materials and Methods section and should provide results for every step/intervention performed. The purpose of the Results section is to convey the data that prove or disprove the hypothesis of your study. Limit the provided results only to those that support the overall aim of the study. The organization of the Results section should parallel the order of the Methods section. The data in this section should be stated in an objective manner without addressing the interpretation of the results. The broad points which should be covered in the Results section are mentioned in Fig. 1.31.7.

1.31: Communication skills in radiology

Manuscript writing in clinical radiology: Instructions, inspiration and insight

The endless voyage

The beginner’s inertia

Pre-requisites of a good manuscript

Publish meaningfully, publish with impact

Understanding the editor’s thought process

Why manuscripts are rejected?

Components of a good radiology manuscript

Title

Abstract and keywords

Introduction

Material/methods

Results

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree