12 Complications of Endoscopic Ultrasound: Risk Assessment and Prevention Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided interventions, including fine-needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNA) and Tru-Cut biopsy (EUS-TCB), have become an accepted part of the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, as well as in benign and malignant pulmonary disorders. In the United States, 60% of gastroenterologists use EUS, and in four European countries ≈ 43% of gastroenterologists and visceral surgeons are reported to have access to EUS.1,2 In Germany, EUS systems are now used not only in university and tertiary referral centers, but also in some 40% of the country’s approximately 2000 hospitals.3 Despite nearly 30years’ experience and a growing number of examinations and interventions, reliable and prospective data on the safety, risks, and complications of diagnostic and interventional EUS are limited.4 Endoscopic ultrasound systems differ from traditional forward-viewing and oblique-viewing endoscopes in the rigidity and stiffness of the tip of the scope, which holds the ultrasound transducer, and in that they have a somewhat larger diameter (12.4–14.6 mm) than gastroscopes (9.0–9.8 mm) or duodenoscopes (11.0–13.1 mm).5 In addition, most echoendoscopes have a longer nonflexible segment just proximal to the transducer. The examination time in EUS is in most cases significantly longer than standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy. With the exception of the electronic radial-scanning echoendoscopes made by Pentax/Hitachi and Fujinon, all other echoendoscopes currently available are oblique-viewing instruments. Intubation and advancement of the echoendoscopes, especially in the esophagus, are therefore semi-blind maneuvers. EUS-FNA and EUS-TCB differ from forceps biopsies in that all of the layers of the nonsterile gastrointestinal tract and sterile extraintestinal anatomical structures are penetrated in order to obtain access to the target organ or structure. The target lesions are often neighboring vascular structures and may have pathological vascularization themselves. For this reason, it is not possible to apply data from studies on the safety of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to endoscopic ultrasound. Complications of Diagnostic EUS Esophageal perforation. In a survey of the members of the American Endosonography Club published in 2001, 86 members reported 16 cervical esophageal perforations among 43 852 upper gastrointestinal EUS procedures with radial echoendoscopes (0.03%).6 Almost all of the patients in whom perforations occurred were elderly; seven of the 16 patients (44%) had a history of difficult intubation in previous endoscopic investigations. Large cervical osteophytes were identified in three cases.

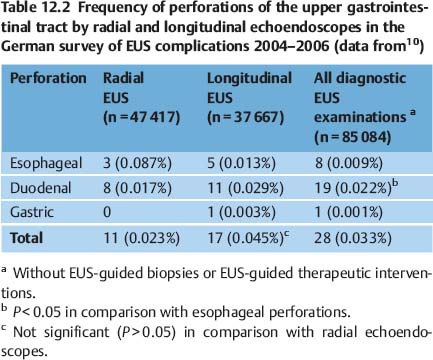

Perforation (Tables 12.1 and 12.2)

Perforation (Tables 12.1 and 12.2)

Risk factor | References |

Lack of operator experience | |

Esophagus |

|

Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction | Das et al. 2001,6 Mortensen et al. 2005,9 Rosch et al. 19937 |

Dilation of esophageal stricture before EUS | |

Advanced patient age | Das etal. 20016 |

Difficult previous endoscopic intubation of the esophagus | Das etal. 20016 |

Large cervical osteophytes | Das etal. 20016 |

Duodenum |

|

Diverticula | |

Stenosis, pancreatic head tumor | Rautetal. 200311 |

Longitudinal echoendoscope (long, rigid tip) | Lachter 200714 |

In nine of the 16 patients with cervical esophageal perforation (56%), the procedure was being performed by an investigator with less than 1 year of experience in endoscopic ultrasonography. Two patients required surgery. In 13 of the 15 surviving patients (87%), the complication was managed successfully with conservative treatment. One patient died.6

Another early multicenter survey from Europe7 reported 13 esophageal perforations in 37915 radial EUS examinations (0.03%), accounting for 68% of all complications. The majority of these patients (77%) had undergone pre-EUS dilation of esophageal strictures to allow complete staging of esophageal cancer, including the celiac lymph-node station.7 Only two studies prospectively investigated the frequency of esophageal perforations. In a single-center study in the Unites States, all patients who underwent EUS of the upper gastrointestinal tract by a single experienced endosonographer over a 7-year period were enrolled. Cervical esophageal perforations occurred in three of 4844 patients (0.06%). The curved-array echoendoscope was used in all three patients.8 In a study from a department of surgical endoscopy in Denmark, complications of EUS in 3324 consecutive patients were investigated. Esophageal perforations occurred in five of 10 patients with complications (0.15% of all investigations, 0.94% of all patients with esophageal cancer). Balloon dilation had been carried out before the EUS examination in two cases. All five patients with esophageal perforation made a full recovery with conservative treatment (n = 4) or surgical treatment (n=1).9 From 2004 to 2006, we performed a survey in German centers performing endoscopic ultrasonography.10 Thirty-two of the 67 centers that responded to the questionnaire reported keeping a prospective registry of complications. Esophageal perforation occurred in only eight of 85 084 reported diagnostic EUS procedures (0.009%). None of the perforations was related to previous dilation of esophageal strictures. Sten-osing esophageal cancer was present in five cases.

Duodenal perforation. In the German survey, duodenal perforations were reported significantly more often than esophageal perforations, occurring in 19 additional cases (0.022%) (Fig. 12.1). In 10 of these 19 cases (47.4%) duodenal diverticula (n = 4), duodenal stenosis (n = 3), duodenal ulcer (n = 1), duodenal scarring (n = 1), or acute pancreatitis (n=1) were reported to have potentially contributed to the perforation. Twenty-seven of the 28 perforations were managed surgically, and all the patients survived10 (Table 12.2).

In a large series of 233 endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsies in patients with presumed pancreatic cancer, Raut and colleagues reported on two cases of duodenal perforation requiring surgical intervention (0.86%). There was no luminal narrowing of the duodenum in either case.11 One case report has been published describing an iatrogenic duodenal perforation during endoscopic ultrasonography, which was managed successfully by endoscopic closure with hemoclips, followed by conservative treatment.12 One duodenal perforation occurred in a series of 224 EUS-FNA procedures, representing one out of five severe complications (complication rate 2.2%).13

Fig. 12.1 Endoscopic view of a retroperitoneal perforation caused by a longitudinal scanning echoendoscope, diagnosed immediately at the time of EUS examination. The indication for the EUS examination was suspected bile duct stones in an 83-year-old woman. The patient recovered soon after the operation (image reproduced with permission from Jenssen et al.10).

A national survey in Israel investigated the mortality rate associated with diagnostic EUS.14 Thirteen of 18 reported cases of death related to EUS (seven in Israel and six from outside the country) resulted from duodenal tears, leading to retroperitoneal perforations. Two further cases occurred as a consequence of esophageal perforations. At least four of six cases of duodenal perforation reported in Israel involved patients with duodenal diverticula. Five of the eight fatal complications in Israel were associated with procedures conducted by examiners with experience of fewer than 300 EUS procedures.14

Endosonographic visualization of the gastrointestinal wall and of adjacent structures depends on appropriate acoustic coupling of the transducer to the gastrointestinal wall, either using a water-filled balloon at the tip of the echoendoscope or of the high-frequency ultrasound miniprobe or by filling the gastrointestinal lumen with water. As water-filling of the upper gastrointestinal tract is frequently used, the low frequency of reported cases of aspiration is somewhat surprising. There have only been three reported cases of aspiration of fluid contents from the upper gastrointestinal tract followed by aspiration pneumonia in endosonographic examinations.14,15

In the Danish prospective study, tracheal suction was needed in 15 of 293 patients (5.1%), and one patient aspirated during the procedure (0.3%). The “water-in-stomach” method was only used in nine patients (3.1%).9

Few data are available concerning the frequency of bacteremia after diagnostic EUS without fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Janssen et al.16 investigated 100 consecutive patients undergoing diagnostic EUS with a curvilinear echoendoscope by obtaining two pairs of blood cultures immediately before and 5 minutes after EUS. Significant bacteremia (Streptococcus viridans and Propionibacterium species; S. mitis) occurred in only two patients (2%), in both cases after an EUS investigation for staging of esophageal cancer (two of nine patients with esophageal cancer).16 Levy et al.17 noted transient bacteremia in one of 52 patients who underwent diagnostic EUS with a radial-scanning echoendoscope (1.9%). None of the three patients with bacteremia after diagnostic EUS in these two studies developed symptoms of infection.16,17

Hematogenous Tumor Cell Dissemination

Hematogenous Tumor Cell Dissemination

Hematogenous tumor cell dissemination was documented in 11 of 45 patients (24%) after transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) staging of rectal cancer. In a further 17 patients (38%), circulating tumor cells were detected in peripheral blood samples before and after TRUS.18 The clinical and prognostic significance of this observation is not clear at present, although data from the same group suggest that detection of circulating tumor cells in blood samples from patients with stage 2 colorectal cancer correlates with a poor outcome.19

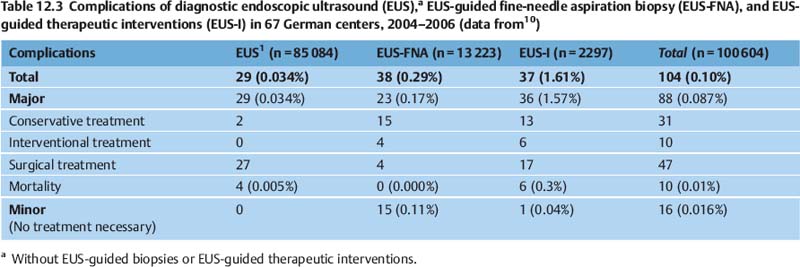

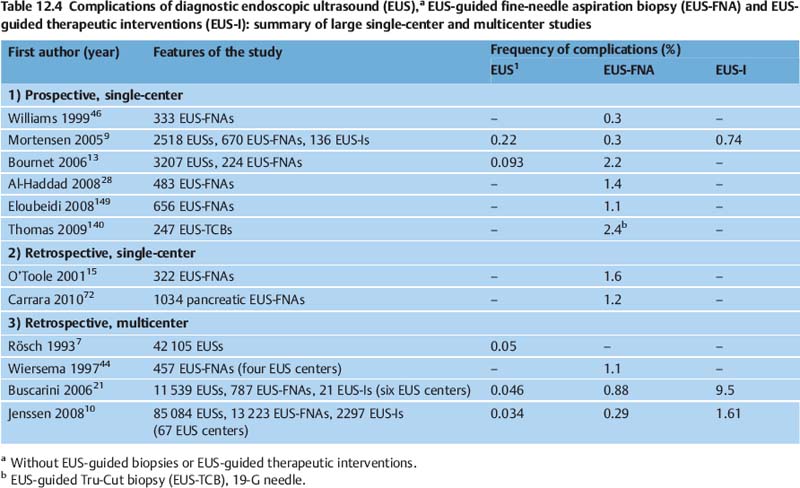

Complications with EUS-Guided Biopsy

Patients who undergo EUS-guided biopsy—EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) or EUS-guided Tru-Cut biopsy (EUS-TCB)—are more likely to experience complications or report symptoms following EUS in comparison with patients undergoing diagnostic EUS (Tables 12.3 and 12.4).10,20,21 The major complications reported with EUS-guided biopsy are infections in cystic lesions, bleeding, and acute pancreatitis.4,22

Bacteremia and Infectious Complications

Bacteremia and Infectious Complications

Bacteremia after EUS-FNA in the upper gastrointestinal tract appears to be a rare event. Its frequency has been investigated in three prospective studies including 202 patients.16,17,23 In one study with 100 patients, all blood cultures obtained 30minutes and 60 minutes after the procedure were negative, except in six patients in whom the culture was positive for coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, which the investigators regarded as a contaminant.23 Among the 102 patients in the studies by Janssen et al. and Levy et al. mentioned above, five patients had bacteremia after EUS-FNA (Streptococcus viridans in three cases; Streptococcus group F; Gram-negative bacillus). No signs or symptoms of infection developed in any of the patients.16,17

Large series reporting EUS-FNA in solid pancreatic masses have noted a 0.4–1.0% rate of febrile episodes.24–26 One case of pyrexia and abdominal pain after EUS-FNA of a large pancreatic head mass, followed by extensive acute portal vein thrombosis, was reported.27

In addition to two cases of fever that resolved on antibiotics after EUS-FNA of lymph nodes, reported in larger studies,28,29 there have been seven reports of serious infectious complications after EUS-FNA or EUS-TCB of mediastinal lymph nodes. After EUS-guided aspiration biopsy of a mediastinal lymph-node metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma, a mediastinal abscess developed. The iatrogenic abscess was treated successfully with EUS-guided drainage and subsequent endoscopic closure of the resulting esophagomediastinal fistula.30 Another mediastinal abscess requiring computed tomography-assisted drainage and subsequent thoracotomy developed following EUS-FNA of a mediastinal metastasis from a malignant teratoma.31 Infectious mediastinitis also occurred as a consequence of transesophageal EUS-FNA of an enlarged necrotic lymph node32 and of a small benign lymph node in the aortopulmonary window.33 In one patient, EUS-FNA of a tuberculous subcarinal lymph node induced multiple symptomatic mediastinal-esophageal fistulas, which resolved in the course of tuberculostatic treatment.34 Only one case has so far been described of infective endocarditis (Streptococcus salivarius) due to EUS-FNA of a mediastinal lymph node in an oncologic patient.35

There have been five published reports ofinfection after EUS-FNA or EUS-TCB of a subepithelial tumor. In one case, EUS-FNA of an esophageal leiomyoma caused severe intramural infection, leading to an esophagectomy.36 In another case, fever developed 2 hours after EUS-FNA of a large mesenchymal tumor of the esophagus, presumably due to left lobar pneumonia.15 In the third case, a large duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) became infected with Enterobacter cloacae following EUS-FNA. The resulting abscess resolved after endoscopic transduodenal drainage and antibiotic treatment.37 Two cases of severe septic complications (streptococcus sepsis, gastric wall abscess) occurred in a series of 52 consecutive EUS-TCBs of gastric subepithelial tumors (3.9%).38 In our own series of EUS-guided biopsies of hypoechoic subepithelial tumors in the stomach, using a 19-G aspiration needle, one septic infection and an extramural abscess (Morganella morganii) also developed in a patient with a large gastric GIST who was receiving 15 mg prednisolone per day (Fig. 12.2).

EUS-FNA of rectal, colonic, perirectal, and pericolic mass lesions appears to be a safe procedure. There have been only two reports of infectious complications following transrectal or transcolonic EUS-FNA of solid mass lesions.39,40 In a prospective risk assessment of bacteremia in 100 patients undergoing EUS-FNA of rectal and perirectal lesions, six patients developed positive blood cultures. Four of these cases were considered to involve contaminants (coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Moraxella, Peptostreptococcus stomatis). Two patients had true-positive blood cultures (Bacteroides fragilis, Gemella morbillorum). No immediate or delayed infectious complications occurred in any patients.41 In two other investigations of the role of EUS-FNA in submucosal tumors and extrinsic masses of the colon and rectum, there were also no complications in 22 and 48 patients, respectively, who underwent transrectal or transcolonic EUS-FNA.42,43

Fig. 12.2a–c Abscess 7 days after EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), with a 19-G aspiration needle, of a large gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the stomach.

a The transabdominal ultrasound image before EUS-FNA.

b EUS-FNA.

c The transabdominal ultrasound image 8days after EUS-FNA, showing a hypoechoic mass (arrows) with irregular margins in the periphery of the tumor (Tu). The patient had fever and abdominal pain, and blood cultures were positive for Morganella morganii.

EUS-FNA of cystic lesions in the retroperitoneal space or pancreas, and particularly in the mediastinum, appears to carry a significant risk of severe infectious complications. In a large multicenter study of EUS-FNA, two of 18 patients with EUS-FNA of a cystic pancreatic lesion without any preprocedural antibiotic prophylaxis developed cyst infections.44 In spite of the substantially growing numbers of EUS-FNA procedures being carried out for cystic lesions in the pancreas, there have only been two reports ofinfection after EUS-FNA of cystic pancreatic lesions despite prophylactic antibiotics.45,46

EUS-FNA of bronchogenic and other mediastinal cysts may cause cyst infection, mediastinitis, and severe sepsis. Foregut duplication cysts account for 6–15% of primary mediastinal masses.47 It may be difficult to differentiate between esophageal bronchogenic cysts and subepithelial tumors or paraesophageal masses because of their hypoechoic and inhomogeneous mucoid contents.48,49 One study showed that in 19 patients in whom a bronchogenic cyst was diagnosed with EUS, 13 cysts were anechoic, while the other six were hypoechoic, suggesting a solid mass lesion. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were diagnostic of a cyst in only four cases.50 In another study, nine of 27 benign mediastinal cysts were misdiagnosed as solid masses on computed tomography.51 There have been reports of eight cases of mediastinitis following EUS-FNA or EUS-TCB of mediastinal mass lesions, which were hypoechoic on EUS and had high computed tomography (CT) attenuation values, but proved to be bronchogenic cysts. As solid lesions were suspected, antibiotics had not been administered in five cases.13,49,50,52,53 In three other cases, severe infection requiring surgical intervention occurred despite preinterventional and postinterventional intravenous antibiotic administration.54 In one other case, asymptomatic contamination of a mediastinal foregut duplication cyst with Candida albicans developed despite preprocedural antibiotic prophylaxis.55 On the other hand, no infectious complications were seen among 22 patients who underwent transesophageal EUS-FNA of suspected mediastinal cysts using peri-interventional antibiotic prophylaxis.48

EUS-FNA of ascites and pleural fluid also involves a risk of infection. Despite antibiotic prophylaxis with levofloxacin in one study, one of 25 patients with transgastric or transduodenal EUS-FNA of suspected malignant ascites developed bacterial peritonitis. Treatment with intravenous antibiotics was successful.56 In another study, two of 60 patients (3%) developed self-limited fever following EUS-guided paracentesis.57 A third study did not report any complications after EUS-FNA of ascites in 31 patients who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics.58

Bile Peritonitis and Cholangitis

Bile Peritonitis and Cholangitis

Bile peritonitis is a severe complication that can develop due to inadvertent penetration or perforation of the common bile duct when EUS-FNA of a pancreatic mass is being performed in patients with biliary obstruction,59 or after failure of an attempt at EUS-guided transduodenal cholangiography or bile-duct drainage.10

An attempt at EUS-guided gallbladder bile aspiration resulted in bile peritonitis in two of the first three patients who were enrolled in a study to identify patients with microlithiasis as a cause of idiopathic pancreatitis. These complications prompted the investigators to discontinue the study.60 Inadvertent gallbladder puncture was a complication of transgastric EUS-guided drainage of an infected pancreatic pseudocyst. Thanks to immediate placement of a nasocystic drain in the gallbladder, only mild and localized bile peritonitis developed and surgery was avoided.61 In an international survey of the indications, yield, and safety of EUS-FNA of liver lesions, one case of death due to septic cholangitis associated with EUS-FNA of a liver metastasis was reported. The background was an occluded biliary stent in a patient with biliary obstruction secondary to pancreatic cancer.62

As a consequence of mechanical irritation caused by the tip of the scope or by a water-filled balloon, endoscopic ultrasonography of the pancreas may cause proximal or distal biliary stent migration, possibly followed by cholangitis.63

Hyperamylasemia is common after EUS-FNA of pancreatic lesions, occurring in 11 of 100 patients in one recent prospective study. However, only two patients developed mild acute pancreatitis.64 Six large studies of EUS-FNA of pancreatic mass lesions have reported iatrogenic acute pancreatitis following EUS-FNA, with rates ranging from 0.4% to 2.0%.15,20,26,46,64,65 A pooled analysis of 4909 EUS-FNAs of solid pancreatic masses from 19 EUS centers in the United States identified 14 cases of iatrogenic postprocedural acute pancreatitis (0.29%).66 The frequency of acute pancreatitis in individual centers ranged from 0% to 2.35%. Only two centers (413 cases of pancreatic EUS-FNA, two cases of acute pancreatitis) assessed complications of EUS-FNA in a prospective manner. Some of the centers with retrospective complication assessment did not report any cases of iatrogenic acute pancreatitis, suggesting that cases of acute pancreatitis may have been underreported for the retrospective cohort. Interestingly, the survey found that half of the patients who had acute pancreatitis after EUS-FNA had benign disease, suggesting that these patients may be at greater risk. Another possible risk factor for iatrogenic acute pancreatitis after EUS-FNA appears to be a history of acute recurrent pancreatitis.66 This observation is in good accordance with experience with percutaneous pancreatic FNA. In the German survey, eight of nine patients (89%) with reported acute pancreatitis turned out to have benign disease after EUS-FNA of pancreatic mass lesions (Table 12.2).10 In a large retrospective series of EUS-FNA in patients with pancreatic cystic lesions, acute pancreatitis occurred in six of 603 cases (1%).45 In a prospective analysis of pancreatic EUS-FNA, pancreatitis did not occur in any of 134 patients with solid lesions, but in three of 114 (2.6%) patients with cystic lesions.15 Two studies investigated the value of EUS-FNA and EUS-TCB in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Mild acute pancreatitis developed in two of 27 patients (7.4%) after EUS-FNA67 and in one of 16 patients (6%) as a consequence of EUS-TCB.68 One very unusual complication was reported very recently: pancreatic ascites developed after EUS-FNA of a small pancreatic tail cyst, most probably due to elevated pancreatic duct pressure caused by an ampullary adenoma.69

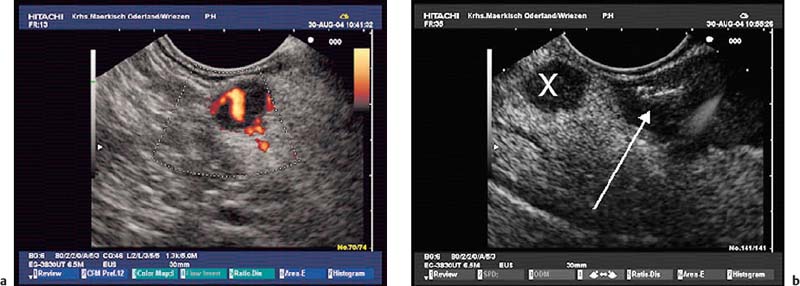

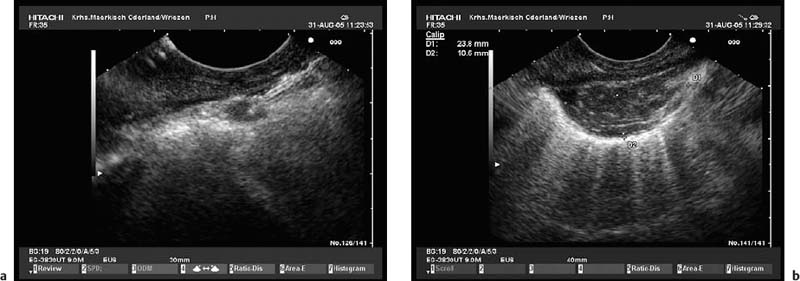

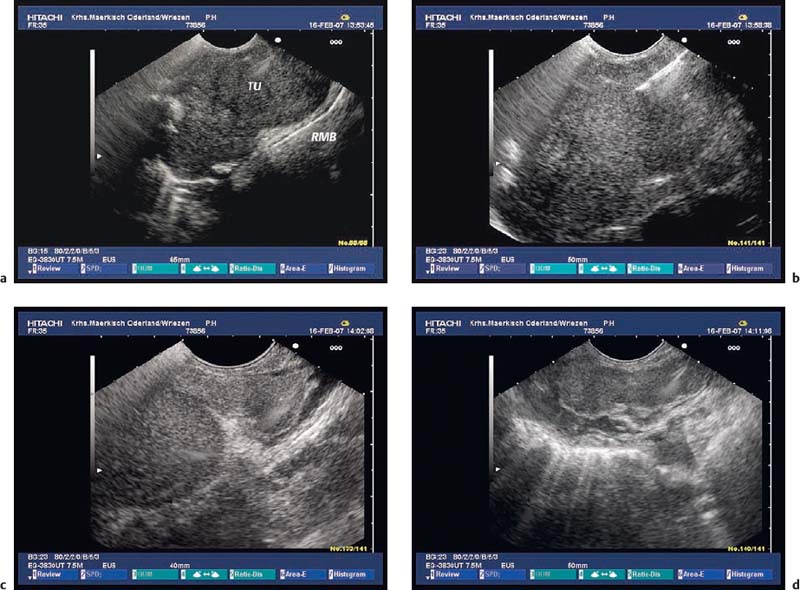

Self-limiting mild intraluminal bleeding due to EUS-FNA has been reported to occur in as many as 4% of cases.25 In a prospective study evaluating the risk of extraluminal hemorrhage caused by EUS-FNA, only three cases of mild extraluminal hemorrhage were observed among 227 patients (1.3%).70 Extraluminal bleeding after EUS-FNA can be visualized with endoscopic ultrasound very well. The bleeding appears as an expanding hyperechoic or hypo-echoic region adjacent to the sampled lesion (Figs. 12.3, 12.4, 12.5, 12.6, 12.7, 12.8, 12.9, 12.10).70

In the survey of German EUS centers mentioned above (13 223 EUS-FNAs; Table 12.3), bleeding was the most common complication of EUS-FNA (0.15% of cases). Mild and self-limiting bleeding after EUS-FNA occurred in 15 patients. Five patients suffered from severe hemorrhages requiring transfusion and in two cases surgical intervention.10 One patient was treated with low-molecular-weight heparin (LWMH) immediately after the procedure and developed a large mediastinal hematoma and hematothorax. Seven units of packed red cells had to be transfused, and thoracoscopy was performed. Another patient needed transfusion of four units of packed red cells after EUS-FNA of pancreatic head carcinoma with portal hypertension. Patients with highly vascularized lesions—for example, subepithelial mesenchymal tumors (Figs. 12.2, 12.4, 12.7), neuroendocrine tumors (Fig. 12.3), and some metastases, as well as patients with cystic lesions (Figs. 12.8, 12.9, 12.11), maybe at greater risk. Inaretrospective study of EUS-FNA of pancreatic cystic lesions in 50 patients, Varadarajulu and Eloubeidi identified three cases of acute intracystic hemorrhage (6%).71 Two patients experienced transient abdominal pain, and none of the three patients required blood transfusions. Intracystic bleeding was readily recognized during the investigation as an expanding hyperechoic area around the site of needle puncture within the targeted cyst (Fig. 12.4). It was not possible to identify any risk factors contributing to the bleeding events. None of the patients with acute intracystic hemorrhage had taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, during the week before the procedure.71 In a large Italian single-center study, bleeding was the most frequent complication of pancreatic EUS-FNA (0.96%, n = 1034), occurring in cystic lesions in seven of 10 cases.72

Fig. 12.3a, b Mild extraluminal hemorrhage (arrow) after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of a small neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor (X).

a Before EUS-FNA.

b Approximately 5 minutes after a second needle pass. The patient did not develop any symptoms.

Fig. 12.4a, b A minute hematoma in the gastric wall after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of asmall subepithelial tumor in a patient with cancer of the large intestine.

a Appearance before EUS-FNA.

b Asmall echogenic intramural hematoma after three needle passes. The EUS-FNA was nondiagnostic; pathological examination following surgical wedge resection revealed a pancreatic rest.

Fig. 12.5a, b Extraesophageal bleeding after endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of a small mediastinal lymph node after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer.

a EUS-FNA.

b The hematoma appeared immediately after the first needle pass.

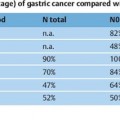

Fig. 12.6a–d

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Aspiration

Aspiration Bacteremia

Bacteremia

Acute Pancreatitis

Acute Pancreatitis Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage