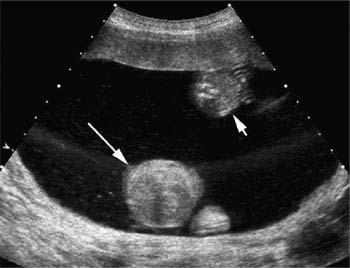

Figure 21.1.1

Twin–twin transfusion syndrome. The two fetal abdomens differ in size, one smaller (short arrow) than the other (long arrow), indicating discordant growth. The thin intertwin membrane (arrowheads) lies close to the smaller twin, because this twin has oligohydramnios while the co-twin has polyhydramnios.

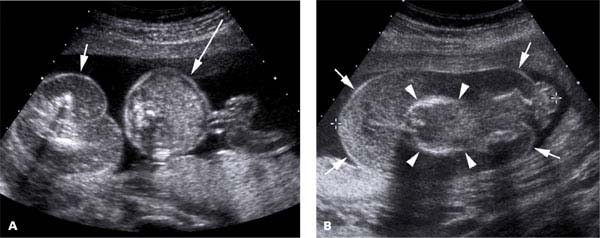

Figure 21.1.2

Twin–twin transfusion syndrome with a “stuck twin”. The two fetal abdomens differ in size, one smaller (short arrow) than the other (long arrow), indicating discordant growth. There is a large amount of amniotic fluid. No intertwin membrane is seen, but the unusual location of the smaller twin, adjacent to the anterior wall of the uterus, indicates that it is held there by the membrane. This twin is termed a “stuck twin” because it is pressed against the uterine wall by the membrane and by the severe polyhydramnios in the co-twin’s sac.

Figure 21.1.3

Twin–twin transfusion syndrome with a hydropic recipient twin. In this monochorionic twin gestation, the two fetal abdomens differ in size, and there is ascites (arrow) in the abdomen of the larger twin.

21.2. Acardiac Twinning

Description and Clinical Features

Acardiac twinning is a rare complication of monochorionic gestations. It occurs as a result of large artery-to-artery and vein-to-vein anastomoses across the common placenta, which disrupt the hemodynamic balance between the twins, such that the cardiovascular system of one twin takes over the cardiovascular system of its co-twin. The twin whose cardiovascular system takes over is termed the pump twin, and the other twin, whose heart usually fails to develop, is termed the acardiac twin. The pump twin’s heart propels blood through its umbilical arteries into the placenta and forces blood across the artery-to-artery anastomoses. This arterial blood then travels in a reverse direction, from the placenta through the acardiac twin’s umbilical artery back to the acardiac twin. The acardiac twin receives its oxygen and nutrition from the incoming arterial blood that originated in the pump twin. Blood travels passively through the acardiac twin and returns through its umbilical vein to the placenta, where it crosses the vein-to-vein anastomoses back to the pump twin.

As a result of the altered hemodynamics, the heart in the acardiac twin is absent or rudimentary. In addition, this anomalous twin often has an abnormal or absent head, small, poorly formed upper extremities, and a two-vessel cord. The lower half of its body tends to be more normally formed, often with normal-appearing spine, kidneys, bladder, and lower extremities. The entire acardiac twin is typically surrounded by massive skin edema, particularly in the upper portion of the body. The acardiac twin continues to grow during gestation.

The prognosis for the pump twin is related to whether this twin develops congestive heart failure in utero and to the size of the acardiac twin. Large acardiac twins may receive a large amount of blood, forcing the pump twin to increase cardiac output significantly. This can lead to hydrops or demise of the pump twin. Overall, the survival rate of pump twins is approximately 50%. The prognosis can be improved if the umbilical cord of the acardiac twin is ligated or occluded with laser before the pump twin develops high-output heart failure.

The amnionicity of an acardiac twin gestation may be monoamniotic or diamniotic.

Sonography

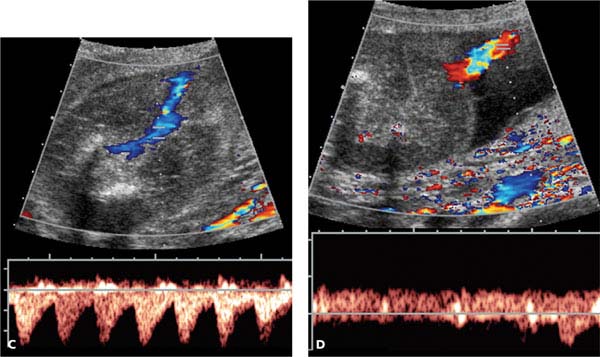

Acardiac twinning is characterized on ultrasound by a monochorionic twin gestation in which one twin, the pump twin, is normally formed and the co-twin, the acardiac twin, is markedly abnormal. The acardiac twin is incompletely formed, often missing the upper trunk, upper extremities, and head (Figure 21.2.1), and is often encased by massive skin edema (Figure 21.2.2). A consistent finding in acardiac twin pregnancies is reversed flow in the umbilical artery and vein of the acardiac twin. Umbilical arterial blood flows toward the acardiac twin and umbilical venous blood flows away from the anomalous twin toward the placenta (Figure 21.2.2).

The pump twin usually appears normal, unless it develops hydrops from high-output congestive heart failure.

Figure 21.2.1

Acardiac twin. A: 3D sonogram of an acardiac twin shows that its head and upper extremities are absent. B: 3D sonogram of the pump twin, which is normally formed.

Figure 21.2.2

Reversed blood flow in umbilical vessels of an acardiac twin. A: The edematous body of an acardiac twin (short arrow) is seen next to the normal abdomen of the pump twin (long arrow). B: Another view of the massively edematous acardiac twin showing marked skin edema (arrows) around the body (arrowheads). C: Spectral Doppler shows pulsatile blood flow toward the acardiac twin in its umbilical artery, reversal of the normal direction. D: Spectral Doppler shows blood flow away from the acardiac twin in its umbilical vein, reversal of the normal direction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree