Chapter 2 Congenital Abnormalities of the Thorax

Several congenital abnormalities of the thorax have been described, but most are rare. Classification of these anomalies is difficult because the embryologic basis often is not clearly understood. A classification based on thoracic anatomic structures uses the categories of trachea, bronchi, lung, and pulmonary vasculature. Congenital abnormalities involving the mediastinum are discussed in Chapter 15, and airway anomalies are discussed in Chapter 13.

The diagnosis usually can be established noninvasively by means of standard radiographs, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A comprehensive listing of congenital abnormalities of the chest is provided in Box 2-1. In this chapter, congenital abnormalities in adults are emphasized. Those more commonly identified in infancy are discussed in Pediatric Radiology: The Requisites.

Box 2-1 Congenital Abnormalities of the Thorax

TRACHEA

Congenital Tracheal Stenosis

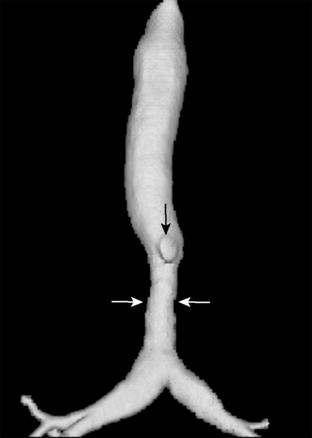

The three patterns of congenital tracheal stenosis are diffuse or generalized hypoplasia; a funnel-like stenosis (i.e., carrot-shaped trachea), often associated with an anomalous origin of the left pulmonary artery (Fig. 2-1); and segmental stenosis. Diffuse or funnel-like stenosis may be associated with absence of the posterior membranous wall due to complete ringlike tracheal cartilages. Patients with complete tracheal rings usually present with respiratory distress in the first few weeks of life, and this condition is associated with a high mortality rate. Rarely, the diagnosis is delayed until adulthood.

Tracheomalacia

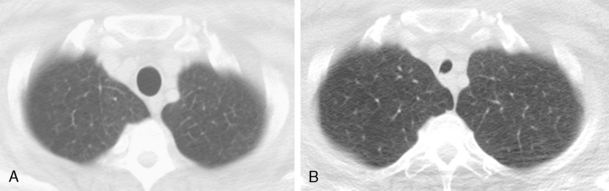

Tracheomalacia is abnormal collapsibility of the trachea, which is caused by softness or pliability of the tracheal cartilages. It may be primary, associated with a localized absence of the tracheal cartilage, or secondary, resulting from external compression, such as from an extrinsic mass. Tracheomalacia must be differentiated from excessive collapse, which is caused by abnormal expiratory pressures. For example, collapse of a long segment of the intrathoracic trachea may occur in late expiration in patients with asthma, chronic bronchitis, and bronchiolitis. Paired inspiratory and dynamic expiratory computed tomography (CT) using state-of-the-art multidetector-row CT scanners is excellent for evaluating tracheomalacia. The accuracy of this technique is comparable to that of bronchoscopy, the gold standard for diagnosing this condition. A greater than 50% collapse of the tracheal diameter is considered abnormal (Fig. 2-2), but healthy individuals may sometimes exceed this threshold.

Congenital Tracheobronchomegaly

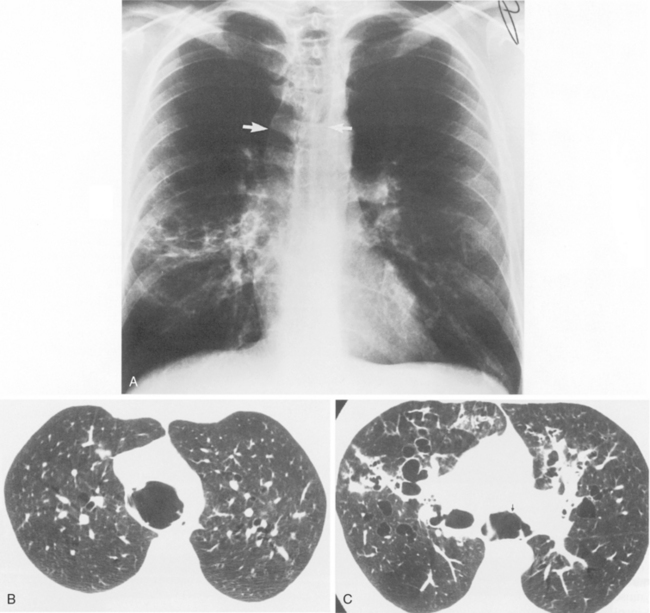

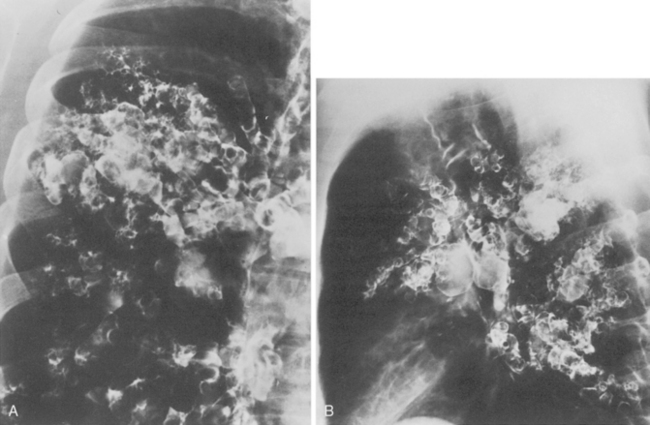

Tracheobronchomegaly (i.e., Mounier-Kuhn syndrome) is characterized by loud, prolonged chronic cough with ineffective secretions and recurrent bronchitis or pneumonia. Imaging of the trachea demonstrates absence or atrophy of elastic fibers and thinning of muscle; airway dynamics are abnormal with dilation on inspiration and collapse on expiration. There are frequent saccular bulgings of the intercartilaginous membranes. The diagnosis can be established by chest radiography when the transverse diameter of the trachea is greater than 25 mm and the diameters of the right and left main bronchi are greater than 23 and 20 mm, respectively (Fig. 2-3). CT can confirm the increased diameter of the trachea. Frequently, there is bronchiectasis in the lung parenchyma.

Aberrant Tracheal Bronchus

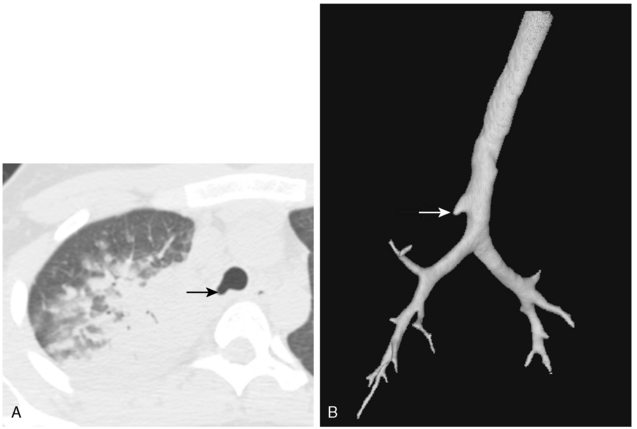

Rarely, the right upper lobe bronchus or a segment of the right upper lobe bronchus may originate in the trachea (i.e., tracheal or pre-eparterial bronchus). This is usually of no clinical consequence. However, in a minority of affected patients, impaired drainage may result in recurrent infections (Fig. 2-4). After endotracheal intubation, the balloon may inadvertently obstruct such a bronchus, causing right upper lobe atelectasis.

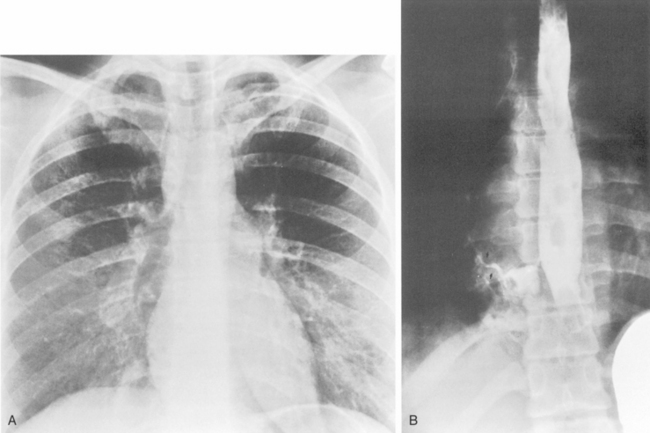

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Congenital tracheoesophageal fistula is invariably a pediatric disease. It occurs in newborns and is most frequently associated with esophageal atresia. However, about 3% of all tracheoesophageal fistulas occur with an otherwise normal esophagus, and patients may present in these instances in adult life. Roughly 75% show communication with the trachea, and the others communicate with the major bronchi (Fig. 2-5). Patients usually have a history of recurrent pneumonias. The chest roentgenogram may show evidence of bronchiectasis. The diagnosis can be confirmed by a contrast esophagogram, which often can identify the fistula and show evidence of contrast material within the tracheobronchial tree and the lung.

BRONCHI

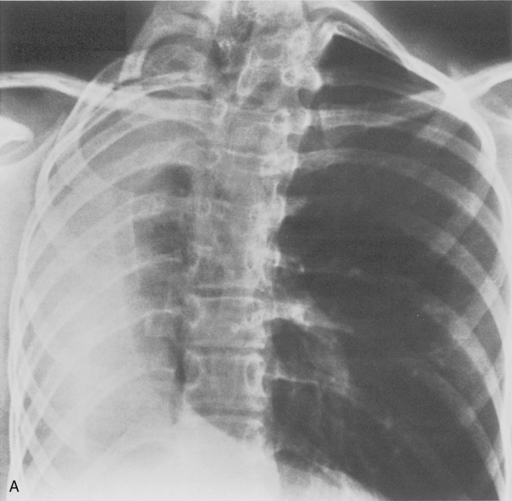

Bronchial Atresia

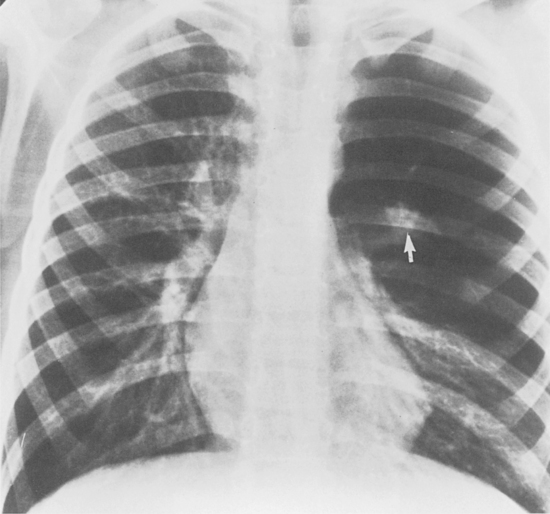

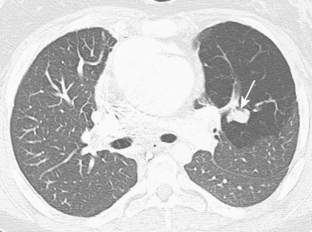

This anomaly consists of atresia of a lobar or segmental bronchus with obliteration of the lumen and preservation of distal structures. The most common site is the left upper lobe, particularly the apical posterior segment. The right middle and upper lobes are less common sites. Mucus secreted within the airways distal to the atretic segment cannot pass the stenosis and accumulates as a mucous plug or mucocele. Collateral air drift keeps the lobe or segment inflated, and it becomes hyperinflated as a result of expiratory air trapping. The chest radiograph shows an area of hyperlucency in the affected portion of the lung (Fig. 2-6). The mucocele appears as an ovoid or branching structure at the hilar level. CT demonstrates the mucoid impaction at the site of obstruction, which is associated with lobar or segmental hyperinflation (Fig. 2-7). There may be an accompanying shift of the mediastinum and compression of the surrounding lung.

Congenital Bronchiectasis

Congenital bronchiectasis (i.e., Williams-Campbell syndrome) is rare, and its existence is controversial. It results from an intrinsic abnormality of cartilage. The cartilaginous deficiency occurs within the fourth- to sixth-order bronchi and is manifested by cystic bronchiectasis and pulmonary hyperinflation (Fig. 2-8). Bronchiectasis, which is acquired and caused by chronic infection, may occur early in life as a result of other congenital, developmental, or genetic disorders. These conditions are listed in Box 2-2 (see Chapter 13).

LUNGS

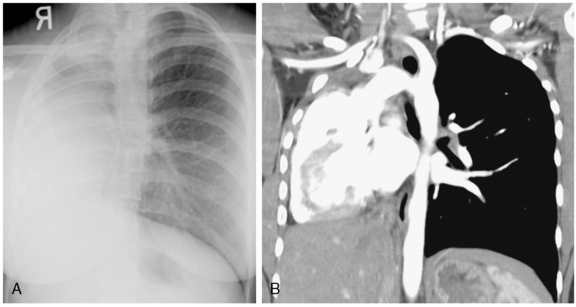

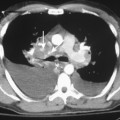

Pulmonary Agenesis and Hypoplasia

Agenesis, aplasia, and hypoplasia more frequently involve the right lung. In agenesis, the radiograph shows complete absence of an aerated lung in one hemithorax, with pronounced reduction in the volume of that hemithorax and associated shift of the mediastinum to the affected side (Fig. 2-9). There is usually pronounced compensatory overinflation of the contralateral normal lung. Pulmonary hypoplasia has similar findings because of volume reduction; however, there is a small lung on the affected side. In some cases, it may be difficult on standard radiographs to distinguish severe pulmonary hypoplasia from aplasia or agenesis. In such instances, CT may help to identify the absence or presence of the ipsilateral pulmonary artery and bronchus or the presence of a rudimentary bronchus in pulmonary aplasia. CT also can demonstrate rudimentary pulmonary tissue in the base of the hemithorax in patients with severe pulmonary hypoplasia and show a patent bronchus and accompanying pulmonary artery (Fig. 2-10).