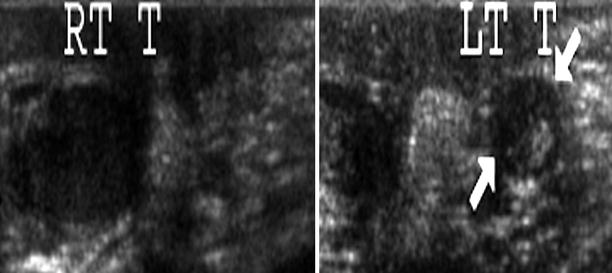

Fig. 6.1

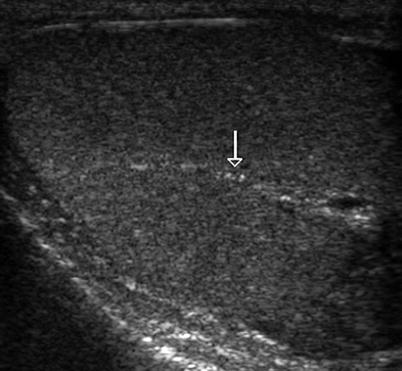

Longitudinal ultrasound image of the right testis reveals homogenous medium-level echogenicity. The tunica albuginea covering the testis can be seen (arrows) anteriorly

The tunica sac typically contains a small amount of serous fluid; larger fluid accumulations are considered non-physiologic.

Imaging Techniques of Testis

Plain Film Radiography

Plain film radiography has no definite role for testicular evaluation. It can demonstrate calcifications in the scrotum in a neonate with meconium peritonitis.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the preferred imaging technique for evaluation of testis anatomy and pathologic lesions of the testis.

One of the most important roles of ultrasound is to differentiate solid from cystic and intratesticular from extratesticular lesions, since most intratesticular solid lesions are malignant, whereas most extratesticular lesions are benign, regardless of whether they are solid or cystic.

High-resolution, real-time ultrasound is nearly 100 % accurate for distinguishing intratesticular from extratesticular lesions. High-frequency sonography can help identify certain benign intratesticular lesions, facilitating testis-sparing surgery.

Computed Tomography

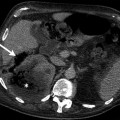

Computed tomography (CT) is used for evaluation of testicular calcifications (Fig. 6.2). It is also used to stage testicular cancer.

Fig. 6.2

Paratesticular calcification. Axial CT image demonstrates incidentally detected calcification at the posterior aspect of the left testis (arrow)

Plain film radiography and CT can aid in the evaluation of peritesticular inflammatory conditions, such as Fournier’s gangrene.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides excellent visualization of testicular anatomy (Fig. 6.3).

Fig. 6.3

Normal testis on MRI. Coronal fat-saturated T2-weighted MRI reveals homogeneous high signal intensity of both normal testes (arrows)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used for characterization of intratesticular masses and can be especially helpful in distinguishing intratesticular hematoma from testicular cancer.

MRI can also be used for staging testicular malignancy.

Both MRI and CT can assist in evaluating cryptorchidism if ultrasound has failed to localize the testis.

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Nuclear scintigraphy allows evaluation of testicular blood flow and therefore may be used for evaluation of testicular torsion.

Digital Subtraction Angiography

Contrast venography is currently used only for embolization therapy of varicoceles.

Ultrasound Examination Technique of the Testis

Scrotal sonography is performed with the patient lying in supine position and the scrotum supported by a towel placed between the thighs. The penis is placed on the abdomen and covered with a towel.

Scrotal ultrasound should be performed with the highest frequency linear array transducer that gives adequate penetration (7–14 MHz).

Examination is performed usually with the transducer in direct contact with the skin, but if necessary a standoff pad can be used for visualization of superficial lesions.

The testes are examined in at least two planes, along the longitudinal and transverse axes, and multiple static images are obtained in each plane.

The size, echogenicity, and vascularity of each testis and epididymis are compared with those on the opposite side.

If the patient is being evaluated for acute unilateral scrotal pain, the asymptomatic side should be examined initially to set the grayscale and color flow Doppler gains for comparison with the affected side.

Color flow Doppler and spectral Doppler parameters are optimized to demonstrate low-flow velocities and blood flow in the testis and surrounding scrotal structures.

Power Doppler ultrasound may also be used to demonstrate intratesticular flow, especially in patients with acute unilateral scrotal pain.

Three-dimensional (3-D) color or power Doppler is an alternative option for displaying the vascular patterns of lesions.

Transverse images with portions of each testis on the same image should be recorded in grayscale and color flow Doppler for comparison purposes.

In patients with small palpable masses, scans should include the area of clinical concern.

Sonographic Anatomy of the Testis

The scrotum is separated by a midline septum (the median raphe), with each half of the scrotum containing a testis, the epididymis, and scrotal portion of the spermatic cord.

Normal scrotal wall thickness is 2–8 mm varying with the degree of cremasteric muscle contraction.

Normal adult testes are symmetric, roughly ovoid in shape, and measure about 5 × 3×2 cm.

The echogenicity of the testis is low to medium in neonates and infants and progressively increases from about 8 years of age to puberty, with the development of germ cell elements.

The tunica albuginea, a fibrous sheath that covers the testicle, appears as a thin echogenic line around the testis sonographically (Fig. 6.1).

The parietal and visceral layers of the tunica vaginalis join at the posterolateral aspect of the testis, where the tunica attaches to the scrotal wall.

The tunica sac covers the testis and epididymis except for a longitudinal strip along the posterior surface of the testis, where the tunica albuginea projects into the interior of the testis to form an incomplete septum, the mediastinum testis.

Sonographically, the mediastinum testis is an echogenic band of variable thickness that extends across the testis in the craniocaudal direction (Fig. 6.4).

Fig. 6.4

Mediastinum testis. Transverse oblique sonogram of the testis reveals a echogenic band (arrow) consistent with normal mediastinum testis

From the mediastinum testis, numerous fibrous septa extend into the testis, dividing it into 250–400 conical lobules, each of which contains one to three seminiferous tubules lined by Sertoli cells and germ cells.

Spermatogenesis occurs within the seminiferous tubules. Each seminiferous tubule is approximately 30–80 cm long; thus, the total estimated length of all seminiferous tubules is 300–980 m.

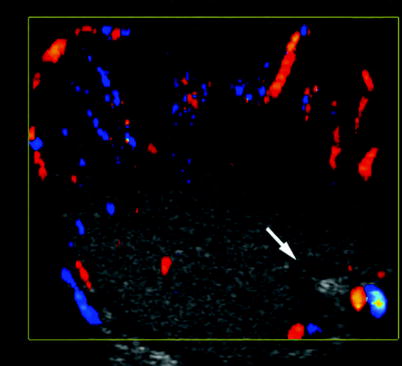

The seminiferous tubules open via the tubuli recti into dilated spaces called the rete testis within the mediastinum. The normal rete testis can be identified at high-frequency ultrasound in 18 % of patients as a hypoechoic area with a striated configuration adjacent to the mediastinum testis (Fig. 6.5).

Fig. 6.5

Rete testis. Transverse oblique color flow Doppler sonography reveals hypoechoic avascular area consistent with normal rete testis (arrow) at the posterior aspect of the right testis

The rete testis, a network of epithelium-lined spaces embedded in the fibrous stroma of the mediastinum, drains into the epididymis through 10–15 efferent ductules.

The epididymis, a tubular structure consisting of a head, body, and tail, is located superior to and is contiguous with the posterior aspect of the testis.

The normal epididymis is best evaluated in a longitudinal view and is homogenous and well defined, and its echogenicity is variable.

The head of the epididymis is a pyramidal structure 5–12 mm in maximum length and mostly isoechoic to the testis, and its echotexture may be coarser than that of the testicle.

The head of the epididymis is composed of 8–12 efferent ducts converging into a single larger duct in the body and tail. This single duct becomes the vas deferens and continues in the spermatic cord.

The narrow body of the epididymis (2–4 mm in diameter), when normal, is usually indistinguishable from the surrounding peritesticular tissue.

The tail of the epididymis is about 2–5 mm in diameter and can be seen as a curved structure at the inferior pole of the testis.

There are four testicular appendages: the appendix testis (hydatid of Morgagni), the appendix epididymis (cranial aberrant ductules), the vas aberrans (caudal aberrant ductules), and the paradidymis (organ of Giraldes). They are remnants of the mesonephric and paramesonephric systems.

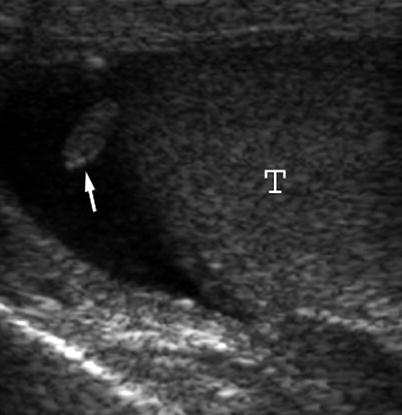

The appendix testis is a small ovoid structure and attached to the upper pole of the testis in the groove between the testis and the epididymis; it is normally hidden by the head of epididymis, making it nearly impossible to differentiate in normal examinations unless it is surrounded by fluid (Fig. 6.6).

Fig. 6.6

Grayscale ultrasound demonstrates appendix testis as an isoechoic structure (arrow) arising from the superior pole of testis (T). The presence of hydrocele permits identification of this structure

The appendix testis has been identified in 92 % of testes unilaterally and 69 % bilaterally in postmortem studies. The appendix epididymis is the same size and echogenicity as the appendix testis but is often pedunculated, is attached to the head of the epididymis, and is encountered unilaterally in 34 % and bilaterally in 12 % of postmortem series. Presence of minimal fluid facilitates their visualization on sonography.

The paradidymis is normally not identified sonographically, but it may swell and distend, forming a cyst-like structure that can be seen sonographically and should not be confused with an epididymal cyst.

The spectral waveform of intratesticular arteries characteristically has a low-resistance pattern, with a mean resistive index of 0.62 (range, 0.48–0.75). These data are not valid for a testicular volume of less than 4 cm3, as is often found in prepubertal boys, when diastolic arterial flow may not be detectable.

Color flow Doppler ultrasound can demonstrate blood flow in a normal epididymis, and the resistive index of a normal epididymis ranges from 0.46 to 0.68.

The testicular veins exit from the mediastinum and drain into the pampiniform plexus, which also receives venous drainage from the epididymis and scrotal wall. These vessels join together, pass through the inguinal canal, and form single testicular veins, which drain into the vena cava on the right and the left renal vein on the left side.

Congenital Lesions of the Testis

Undescended Testis (Cryptorchidism)

General Information

The testes remain near the internal inguinal ring until the third trimester and generally have entered the scrotum at term.

Cryptorchidism is defined as complete or partial failure of the intra-abdominal testis to descend into the scrotal sac.

It is estimated that approximately 9.2–30 % of premature boys, 3.3–5.8 % of full-term neonates, 0.8 % of infants aged 1 year, and 0.5–0.8 % of adults older than 18 years have a truly cryptorchid testis.

Bilateral cryptorchidism is seen in patients with prune belly syndrome and androgen insensitivity syndrome.

Palpable testes outside the scrotum may be cryptorchid, ectopic, or retractile; non-palpable testes may be cryptorchid, atrophic, or absent.

Orchiopexy is the treatment of choice and usually performed in patients aged 2–10 years.

The main indications for orchiopexy are to preserve the fertility potential and, by placing the gonad in an accessible location, to facilitate the detection of a tumor if it develops later on in adult life.

Undescended testis can be categorized on the basis of physical and operative findings:

True Undescended Testis

The testis fails to descend into its normal postnatal location in the scrotal sac but can be found along the normal path of descent and has a normally inserted gubernaculum. Cryptorchid testis may be found in the abdomen (intra-abdominal), in the inguinal canal (canalicular), or just at the external ring (prescrotal). The most common locations of cryptorchid testes are as follows: in the inguinal canal (72 %), prescrotal (20 %), and abdominal (8 %).

Ectopic Testis

The testis descends through the inguinal canal, past the external inguinal ring, but does not assume its normal location in the scrotum. Ectopic testes may be found in the perineum, femoral canal, superficial inguinal pouch (most common location), suprapubic area, or contralateral hemiscrotum (transverse ectopia – the rarest form).

Retractile Testis

It is not a cryptorchid testis. Testis intermittently retracts out of the scrotum due to an active cremasteric reflex and appears at the external inguinal ring. It can be observed in up to 80 % of patients aged 6 months to 11 years.

Absence of the testis occurs in 3–5 % of surgical explorations for cryptorchidism.

Undescended testes are at increased risk for infertility, trauma, torsion, and development of malignancy.

Infertility can be observed in 40 % of patients with unilateral and 70 % of patients with bilateral cryptorchidism.

Cryptorchid testes are considered to be more prone to testicular torsion than normally descended testes; the extent of the increased risk is difficult to ascertain from available literature.

The frequency of cryptorchidism in patients with germ cell tumors varies from 6.5 to 14.5 %.

The risk of developing a testicular germ cell tumor in a patient with cryptorchidism is increased approximately 3.5–5.0 times over that of a control population. In patients with unilateral cryptorchidism, the non-cryptorchid testis is also more at risk of developing a germ cell tumor, but the risk is less than for the cryptorchid testis.

Germ cell tumors arising in cryptorchid testes are disproportionately seminoma, rather than non-seminomatous germ cell tumors.

Orchiopexy does not alter the risk of development of malignancy in a cryptorchid testis.

Imaging

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the preferred initial imaging modality to assess cryptorchidism, because of the superficial location of most cryptorchid testes (Fig. 6.7a–c). The presence of an oval mass in the inguinal canal (relatively hypoechoic in echotexture with echogenic mediastinum) is diagnostic. Undescended testis is usually smaller and less echogenic than the normal testis (Fig. 6.8).

Fig. 6.7

Cryptorchidism. (a) Longitudinal ultrasound image of the right inguinal region demonstrates an oval slightly hypoechoic structure (arrows) consistent with cryptorchid testis located in superficial inguinal pouch. (b) Longitudinal power Doppler sonogram demonstrates normal vascularization of cryptorchid testis. (c) Longitudinal sonogram of the right inguinal region shows an oval isoechoic cryptorchid testis (arrows) and associated cystic mass. This mass extends to inguinal canal and surgically confirmed as spermatic cord cyst

Fig. 6.8

Atrophy of the testis. A 1.5-year-old boy was referred to ultrasound for follow-up examination. He had history of orchiopexy operation before 6 months. Longitudinal grayscale ultrasound reveals normal-sized right testis and atrophic left testis (arrows)

Dynamic evaluation is useful for diagnosing retractile testis (Fig. 6.9a–c). Persistence of pars infravaginalis gubernaculi has been mistaken for the testis. The presence of an echogenic band (mediastinum testis) identifies the maldescended testis.

Fig. 6.9

Retractile testis. (a) Transverse oblique grayscale sonogram demonstrates both testes within the scrotal sac. Left testis is larger than right testis due to intratesticular mass (not visible in this image clearly). (b) Transverse grayscale image reveals left testis containing intratesticular mass (arrow) pathologically proven as Leydig cell tumor (c) image was obtained within minutes after (a) image. Transverse image of right inguinal region (c) image reveals right retractile testis located on superficial inguinal pouch

Computed Tomography

If ultrasound cannot identify the testis, MRI and CT are the subsequent modalities of choice.

Laparoscopy is performed if MRI and CT cannot localize the testis.

On CT examination, a cryptorchid testis is seen as an oval soft tissue mass along the expected course of testicular descent.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is performed from the level of the kidneys to the level of the pelvic outlet. The pulse sequences used are T1-, T2-, and postgadolinium T1-weighted images in the axial and coronal planes.

An oval mass that appears as low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images is characteristic of an undescended testis. Identification of the mediastinum testis is helpful.

CT and MRI are much better than ultrasound in detecting an undescended testis that is located in abdomen (Fig. 6.10a–e).

Fig. 6.10

Undescended testis. (a) Fat-saturated T2-weighted coronal image reveals left testis (arrow) within scrotum. Right testis is not visible in the scrotal sac. (b) T1-weighted axial image demonstrates undescended testis (arrow) with low signal intensity. (c) T2-weighted axial image demonstrates undescended testis (arrow) with high signal intensity. (d) Fat-saturated T2-weighted coronal images reveal oval-shaped right testis (arrow) within the right inguinal canal. Signal intensity of testis is similar to muscle on T1-weighted image and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Size of undescended right testis is smaller than normal left testis. (e) Diffusion-weighted axial MR image reveals high signal of right testis within inguinal canal (arrow)

Diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DWI) is a new MR technique which measures the random motion of water molecules in tissue. According to our limited experience, it is useful for identifying undescended testes (Figs. 6.10e and 6.11a, b).

Fig. 6.11

Undescended testis. (a) T2-weighted axial image shows left testis (arrow) located in superficial inguinal pouch. (b) Diffusion-weighted axial MR image reveals high signal intensity in the left testis (arrow)

Testicular Venography

Testicular venography has fallen out of favor because of the availability of noninvasive tests. Demonstrating presence of the pampiniform plexus, visualization of testicular parenchyma, and a blind-ending testicular vein (usually indicates absent testis) are diagnostic.

Angiography is accurate but invasive; thus, it is not preferred.

Pathology

Undescended testes are typically smaller than their normally descended counterparts (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12

Undescended testis. Undescended testes are typically smaller than their normal counterparts. This testis was removed from an 18-year-old male who had undergone orchiopexy for an undescended testis at age 1 year. The testis did not grow after the onset of puberty. It was excised and replaced with a prosthesis (Image courtesy of Edmund Reineks, M.D.)

The histologic findings in testicular biopsies prior to the onset of puberty generally reflect a spectrum of germinal cell hypoplasia ranging from minimal to severe.

In cryptorchid testes that remain in the abdomen or inguinal canal through puberty, spermatogenesis is typically absent.

The seminiferous tubules are small, with thick, hyalinized walls.

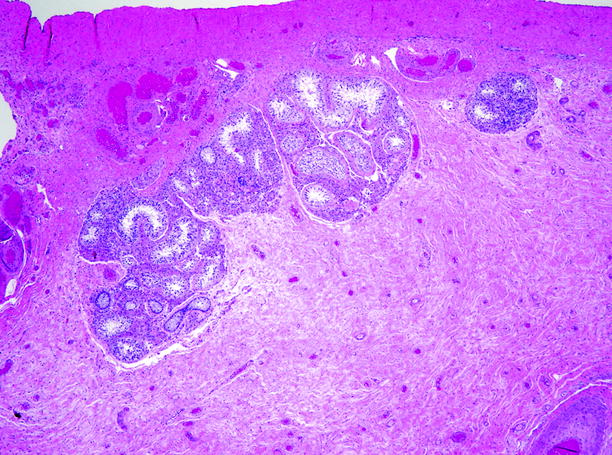

The tubules may contain Sertoli cells and spermatogonia only, they may contain Sertoli cells only, or their lumens may be obliterated by hyalinization (Fig. 6.13).

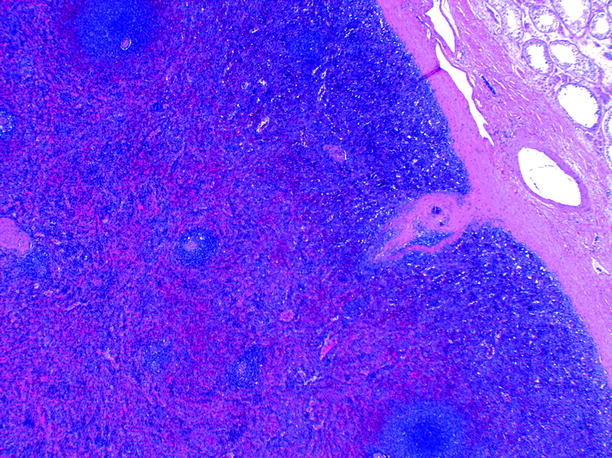

Fig. 6.13

Undescended testis. This 20-year-old man presented with an inguinal hernia associated with an undescended testis, which was excised at the time of hernia repair. Much of the parenchyma consists of hyalinized scar tissue. The lumens of the few remaining seminiferous tubules were lined by Sertoli cells only; no germ cells were found

Leydig cells are present in the interstitium, often arranged in large aggregates that suggest hyperplasia, although the absolute number of Leydig cells is diminished.

Differential Diagnosis

A lymph node can be differentiated readily by the presence of fatty hilum and its characteristic location.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Ultrasound can localize a cryptorchid testis in inguinal canal.

MRI is better to localize intra-abdominal cryptorchid testis.

Bilateral cryptorchidism occurs in prune belly syndrome and androgen insensitivity syndrome.

Ambiguous Genitalia

General Information

Ambiguous genitalia may be a manifestation of female pseudohermaphroditism, male pseudohermaphroditism, true hermaphroditism (ovotesticular), mixed gonadal dysgenesis, and pure gonadal dysgenesis.

Presence of testes excludes female pseudohermaphroditism because ovaries do not descend.

Imaging

Genitography

Genitography may demonstrate male- or female-type urethral configuration and any fistulous communication with the vagina or rectum.

Presence or absence of the vagina, relationship of vagina to the urethra, the level of the external sphincter, and cervical impression may be evaluated.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the primary imaging modality for assessing presence or absence of gonads and müllerian derivatives.

Inguinal, perineal, renal, and adrenal regions should be scanned carefully.

The presence or absence of a uterus can be assessed by pelvic sonography.

Ultrasound can also demonstrate undescended testes and prostate gland of male infant (Fig. 6.14a–c).

Fig. 6.14

Newborn baby with ambiguous genitalia was referred for ultrasound evaluation. (a) Transverse pelvic sonogram reveals oval hypoechoic structure (calipers) behind the bladder consistent with prostatic tissue of male baby. (b) Transverse sonogram of right inguinal region shows right testis (calipers) within the inguinal canal and associated hydrocele. (c) Transverse sonogram of left inguinal region reveals left testis (calipers) within the inguinal canal

The commonest cause of female pseudohermaphroditism is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). In CAH patients, ultrasound typically shows enlargement of both adrenal glands with demonstrable corticomedullary differentiation. Surface lobulation on the adrenal glands, with stippled echogenicity, is another ultrasound finding.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Both T1- and T2-weighted MRI sequences should be used in evaluation of ambiguous genitalia.

MR imaging is more sensitive than ultrasound in the evaluation of gonads. Presence of intra-abdominal gonads cannot be excluded even if MRI does not demonstrate intra-abdominal testes. In such situations surgical exploration is done.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Normal MRI findings cannot exclude presence of intra-abdominal gonads.

Splenogonadal Fusion

General Information

Splenogonadal fusion is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by abnormal coalition of splenic and gonadal tissue in utero.

A segment of aberrant splenic tissue is found within the scrotum or pelvis fused to the normal gonad either continuously or discontinuously.

Lesions occur most often on the left (98 %) and most often involve the testis (95 %).

In the continuous type, there is a cord of ectopic splenic tissue or fibrotic tissue connecting the spleen to the testis. This form is often associated with other congenital anomalies.

In the discontinuous type, no demonstrable connection to the spleen is present, and the ectopic splenic tissue is attached to the testis and lies within the tunica albuginea but is separated from the testis by a fibrous capsule. This type is rarely associated with other congenital anomalies.

Preoperative diagnosis is difficult and surgical exploration is made usually to rule out malignancy. Imaging with sulfur colloid may be helpful.

Imaging

Ultrasound

Sonographically, the lesion appears as homogenous isoechoic mass equal with echogenicity of the normal testis (Fig. 6.15).

Fig. 6.15

Splenogonadal fusion. Transverse color flow Doppler image shows normal left testis within the scrotum (upper part of the figure). Transverse grayscale ultrasound reveals a 13 × 10 mm isoechoic mass lesion located near the upper pole of the left testis (left lower part of figure; calipers 1,2). This mass was removed surgically and confirmed as splenic tissue consistent with discontinuous-type splenogonadal fusion. An anechoic epididymal cyst was also found 10 × 3 mm in size within left caput of epididymis (right lower part of figure; calipers 3,4) (Courtesy of Dr. A. Kursad Poyraz, M.D.)

The mass is well defined and is not associated with scrotal skin thickening or hyperemia.

Color flow Doppler ultrasound may demonstrate vascularity within the lesion.

Computed Tomography

MDCT has no definite role.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Multiplanar imaging capability of MRI may demonstrate the relation between spleen and gonad as continuous or discontinuous.

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Technetium-99m sulfur colloid scintigraphy can show ectopic uptake within the scrotum.

Pathology

Splenic and gonadal tissues sometimes fuse as the fetus develops.

With fetal growth, a connection may be maintained between the gonad and the normal spleen in the form of a fibrous cord (continuous splenogonadal fusion). The cord may consist mainly of splenic tissue or may contain small nodules of splenic tissue.

In some instances, a connecting cord is absent (discontinuous splenogonadal fusion).

Affected testes are undescended in one-sixth of cases, and an inguinal hernia is present in one-third of cases.

In most cases, the condition presents as a palpable inguinal or scrotal mass, or the lesion is found incidentally at the time of orchiopexy or hernia repair.

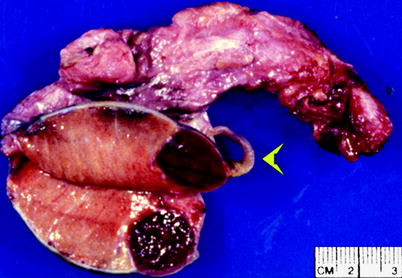

The splenic tissue forms a circumscribed red nodule adjacent to the testis, most frequently at the upper pole, less often at the lower pole, and, rarely, within the testis (Fig. 6.16).

Fig. 6.16

Splenogonadal fusion. The splenic tissue appears as a circumscribed red nodule at one pole of the testis. In some cases, a fibrous cord (arrowhead) maintains some continuity between the spleen and the testis as it descends; the cord may contain elements of splenic tissue (From MacLennan et al. (2003), with permission)

Splenic nodules are rarely larger than 1.0 cm in diameter.

They consist of normal splenic tissue, separated from the normal testicular parenchyma by a fibrous interface (Fig. 6.17).

Fig. 6.17

Splenogonadal fusion. The red nodule is composed of normal splenic tissue, on the left, separated from the normal testicular tissue at upper right by a fibrous interface (Image courtesy of Liang Cheng, M.D.)

Polyorchidism

General Information

Polyorchidism is a rare congenital anomaly of the urogenital system and is defined as the presence of more than two testes within the scrotum. About 100 cases have been reported in the literature.

Supernumerary testis is most often located on the left side, and there are two epididymides and a single vas deferens.

In approximately 75 % of cases, the supernumerary testes are intrascrotal, and the patients most often present with a painless scrotal mass. Of the remaining cases, 20 % of the testes are inguinal and 5 % retroperitoneal. The testes may have separate or common spermatic cords, epididymis, and tunica albuginea.

Triorchidism is the most common type of polyorchidism.

The extra testis may have to be removed because of possible complications such as torsion or increased malignancy risk.

Imaging

Ultrasound

At ultrasound, a supernumerary testis usually has the same echo pattern as the ipsilateral testis, and it appears as a well-defined, homogeneous echogenic mass located superior or inferior to the ipsilateral testis (Fig. 6.18a, b). The presence of a mediastinum testis confirms a supernumerary testis.

Fig. 6.18

Polyorchidism. Oblique ultrasound scans on the right (a) and left (b) hemiscrotum. A single testis (T) is identified on the right (a), while on the left (b) ultrasound shows an oval mass (*) with the same echogenicity and echotexture similar to that of the left testis (T), consistent with the presence of an accessory testis

The supernumerary and ipsilateral testes may appear attached or separated. A supernumerary epididymis adjacent to the supernumerary testis may be seen. Color flow Doppler demonstrates normal flow pattern.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is more suitable to demonstrate supernumerary testes in same plane (especially in coronal plane).

Signal characteristics are identical to the adjacent normal testis (Fig. 6.19a, b). MRI demonstrates a round or oval structure with homogeneous intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.

Fig. 6.19

Polyorchidism. (a) T1-weighted axial and (b) T2-weighted axial images of scrotal region demonstrate three testes within the scrotal sac consistent with polyorchidism (R right testis, L left testis, SN supernumerary testis)

Testicular Microlithiasis

General Information

Testicular microlithiasis is an uncommon condition that is identified in 1.4–2 % of patients referred for scrotal sonography.

Testicular microlithiasis is associated with a wide variety of conditions (see Table 6.1). It is also seen in otherwise normal children and patients studied for other diseases. In adults, microliths are commonly seen in cryptorchid testes and those that have undergone orchiopexy, in testes of infertile patients, and in testes of patients complaining of orchialgia or testicular asymmetry.

Table 6.1

Associated disorders with testicular microlithiasis

Testicular germ cell tumors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access