Congenital Disease

Congenital Spinal Stenosis

No measurements are absolute; however, AP dimensions of the spinal canal less than 10 mm in the cervical region ( Fig. 3.14 ) and 12 mm in the lumbar region (see Fig. 3.7) are considered to be stenotic. To some extent canal dimensions are more critical in the cervical spine, due to the presence of the cord, and in this region AP diameters of 10 to 13 mm are considered to represent relative spinal stenosis. It should be noted that the normal dimensions of the cervical spinal canal vary according to anatomic level, sex, age, and height. One easily recognized imaging finding in congenital spinal stenosis of the lumbar region is tapering of the canal dimension from the upper to the lower lumbar levels, with this region normally equal in size or greater in dimensions when compared to the thoracic spine. Patients with congenital cervical spinal stenosis are predisposed to traumatic spinal cord injury. Clinical presentation with congenital cervical spinal stenosis is typically due to myelopathic symptoms. However, radicular symptoms may be present, in either cervical or lumbar congenital stenosis, due to nerve root impingement with narrowing of the lateral recesses or neural foramina. A major element of congenital spinal stenosis is short pedicles. Achondroplasia is well known for symptomatic lumbar stenosis, with the entire spine stenotic in some patients. Down syndrome is known for congenital stenosis of both the cervical and lumbar spine.

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is simply lateral curvature of the spine. Ninety percent of cases are idiopathic with no underlying cause. The typical idiopathic scoliosis is an S-shape curve, with the thoracic curvature convex to the right. The remaining 10% are congenital ( Fig. 3.15 ), neuromuscular, and post-traumatic in etiology. In congenital scoliosis, vertebral anomalies can be seen (e.g., a hemivertebra) ( Fig. 3.16 ) and in other instances the scoliosis is associated with a congenital abnormality such as diastematomyelia or a Chiari I malformation (with hydromyelia). Neuromuscular causes include cerebral palsy, with an incidence as high as 50% in patients with severe disability as assessed by the gross motor function classification system. Posttraumatic etiologies include prior fracture, chronic osteomyelitis, prior surgery, and radiation therapy. Plain films are utilized for quantitation of the curvature and monitoring for possible progression. MR is the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of atypical or progressive scoliosis, specifically to exclude an underlying abnormality, with coronal imaging important (in addition to the more routinely acquired sagittal and axial scans).

Tethered Cord

This congenital anomaly is defined by a low position of the conus, with the conus being tethered (held in that position) due to an additional abnormality. Causes include a tight (often slightly thickened) filum terminale, lipomyelomeningocele (and variants thereof), diastematomyelia, and retethering following meningomyelocele repair ( Fig. 3.17 ). The clinical presentation is typically that of a young child with progressive neurologic dysfunction, specifically gait disturbance, motor and sensory loss in the lower extremities, and bladder dysfunction (all presumably due to cord traction and ischemia). In a tight filum terminale there will be an identifiable conus. The most common appearance of a tethered cord, however, is that of the cord extending without change in caliber to the lumbosacral region, tethering posteriorly with an associated lipoma and dysraphic posterior spinal elements. There may be associated hydromyelia. Treatment is surgical with release of the tether, for prevention of symptom progression. Following release, the level of the conus/distal cord typically will not change.

Syringohydromyelia

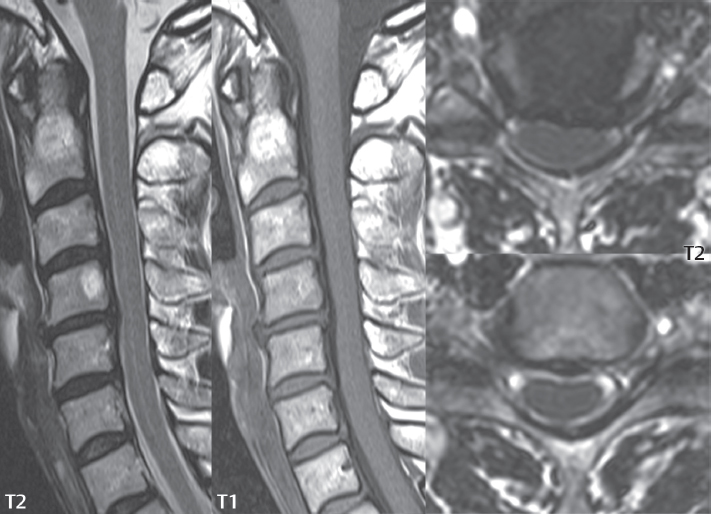

Hydromyelia is strictly defined as dilatation of the central canal of the spinal cord, lined by ependyma. Syringomyelia is defined strictly as the presence of a fluid-filled cavity within the spinal cord, lined by gliotic parenchyma, specifically not representing dilatation of the central canal. Unfortunately, these terms are commonly confused, and used interchangeably, by physicians. Thus the term syringohydromyelia has emerged, being less specific and including both hydromyelia and syringomyelia. Syringobulbia refers to the extension of a fluid collection into the brainstem, often accompanied by cranial nerve findings (due to compression). These entities are all difficult to visualize on CT. MR well depicts the cord and any pathology therein, and specifically abnormal fluid collections. The sagittal plane is commonly used to define the extent of syringohydromyelia, with the axial plane providing localization relative to the cross-section of the cord. Axial images also better identify very small cavities, and can determine with greater certainty the true extension of hydromyelia (with minimal dilatation of the central canal difficult to assess on sagittal images due to partial volume effects). Neoplastic disease and trauma are common etiologies for syringomyelia, whereas the Chiari I and II malformations account for the majority of cases of hydromyelia ( Figs. 3.18 and 3.19).

Intravenous contrast administration is strongly recommended in patients with syringomyelia, improving the sensitivity for detection of neoplastic disease. In the patient population at large, hydromyelia is much more commonly encountered, congenital in etiology, than syringomyelia due to either neoplasia or trauma. Both syringomyelia and hydromyelia can be treated by direct shunting of the cavity, amongst other options. An enlarging syrinx in a post-traumatic patient, for example following cervical cord injury, can cause neurologic deterioration unless so treated. With MR imaging at 3T now commonly available clinically, the normal central canal of the spinal cord is routinely visualized on high-resolution images, with the canal slightly smaller or larger (specifically with a range of normal diameters) depending on the individual ( Fig. 3.20 ).

Meningomyeloceles and Lipomyelomeningoceles

In a meningomyelocele and a meningocele, there is incomplete closure of the posterior bony elements, with the contents of the spinal canal extending through the defect (open spinal dysraphism) ( Fig. 3.21 ). A meningocele, by definition, contains only dura and arachnoid, with neurologic deficits uncommon. A meningomyelocele, by definition, contains neural tissue within the expanded posterior subarachnoid space, with cord tethering. Imaging studies are rarely acquired at presentation in the newborn, with the exposed neural placode readily evident (in a meningomyelocele) and surgery typically performed within 48 hours ( Fig. 3.22 ). MR and CT are often obtained many years following surgery, and demonstrate a wide dysraphic defect with an accompanying CSF-filled sac covered by skin. Retethering is a common long-term complication. It is important to note that Chiari II malformations are virtually always associated with a meningomyelocele ( Fig. 3.23 ).

Lipomyelomeningoceles (and lipomyeloceles) differ from the two entities just described by the presence of a lipoma attached to the dorsal surface of the cord termination and intact skin overlying the defect (closed spinal dysraphism) ( Fig. 3.24 ). The lipoma extends through the dysraphic spinal canal merging with and becoming indistinguishable from, subcutaneous fat. The distal cord is tethered by the lipoma. When a mass is present posteriorly, it presents clinically under the age of 6 months ( Fig. 3.25 ). If the mass is subtle, presentation may not be until 5 to 10 years of age when neurologic or urologic deficits are noticed. Occasionally this entity goes undetected until adulthood, since the lesion is skin-covered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree