, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

Consolidation on CT scans refers to a pattern of pulmonary abnormality that appears as a homogeneous increase in lung parenchymal attenuation that obscures the margins of vessels and airway walls. Air-bronchogram sign may be present within the lesion [1] (Fig. 3.1). Pathologically, the consolidation consists of an exudate or other product of disease that replaces alveolar air, rendering the lung solid (as in infective pneumonia) [2].

Lobar Consolidation

Definition

Consolidation on CT scans refers to a pattern of pulmonary abnormality that appears as a homogeneous increase in lung parenchymal attenuation that obscures the margins of vessels and airway walls. Air-bronchogram sign may be present within the lesion [1] (Fig. 3.1). Pathologically, the consolidation consists of an exudate or other product of disease that replaces alveolar air, rendering the lung solid (as in infective pneumonia) [2].

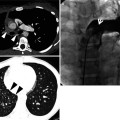

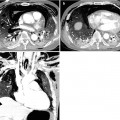

Fig. 3.1

Lobar pneumonia in a 74-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia and neutropenic fever. Urine culture disclosed gram-positive cocci. (a, b) Thin-section (2.5-mm section thickness) CT scans at levels of the right upper (a) and middle lobar (b) bronchi, respectively, show lobar parenchymal opacity involving the right upper and middle lobes. (c, d) Coronal reformatted images at levels showing the right upper lobar bronchus (RUB) (c) and right middle lobar bronchus (RMB) (d), respectively, demonstrate parenchymal opacity in the right upper and middle lobes. Also note crazy-paving appearance (arrows in c) within parenchymal opacity lesion

Diseases Causing the Pattern

Lobar consolidation is the representative pattern of lobar pneumonia. The lobar pneumonia is one of the two morphologic classifications of pneumonia (the other being bronchopneumonia) (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2). The most common organisms causing lobar pneumonia are Streptococcus (Pneumococcus) pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis may also cause lobar pneumonia [3] (Table 3.1).

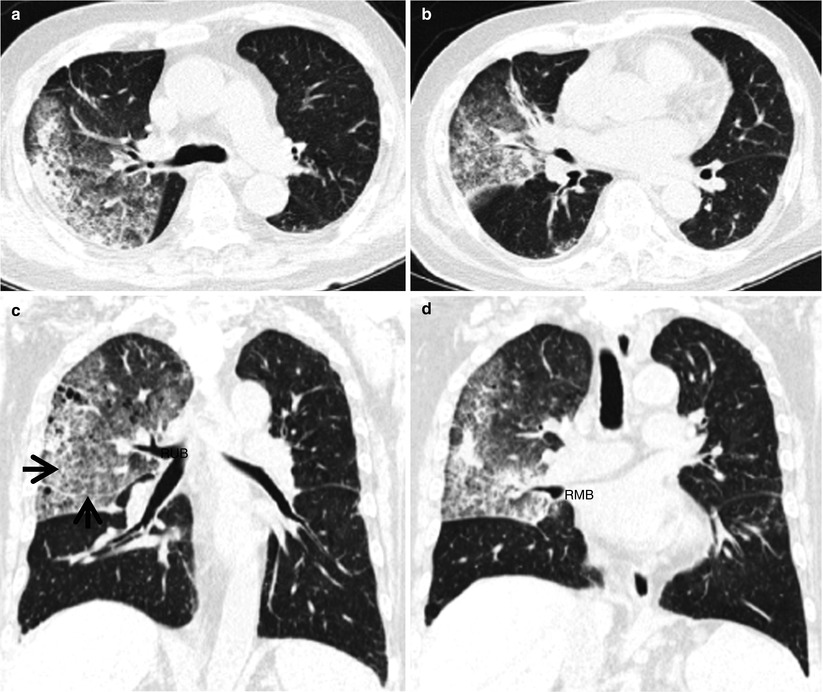

Fig. 3.2

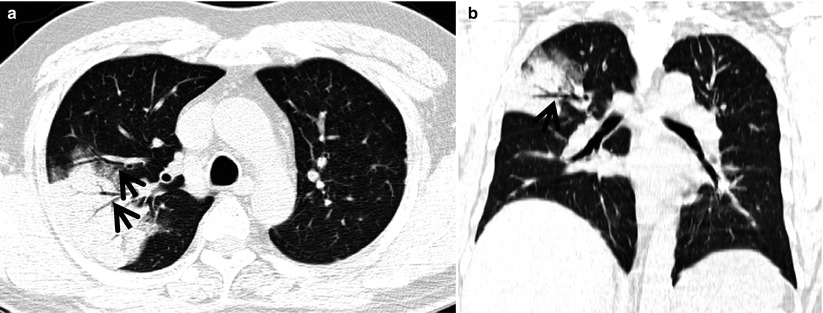

Segmental pneumonia as community-acquired pneumonia in a 38-year-old man. (a, b) Transverse (a, 2.5-mm section thickness) and coronal (b, 2.0-mm section thickness) reformatted CT images show segmental consolidation in posterior segment of the right upper lobe. Please note CT air-bronchogram signs (arrows). Patient proved to have Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia

Table 3.1

Common diseases manifesting as lobar consolidation

Disease | Key points for differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

Lobar pneumonia | Acute pneumonia symptoms, homogeneous airspace consolidation with air bronchograms |

Mucinous adenocarcinoma | Consolidation; stretching, squeezing, and widening of the branching angle of CT air-bronchogram sign and bulging of the surrounding interlobar fissure; MRI white lung sign |

BALT lymphoma | Indolent and slow progressive nature of consolidative lesion |

Pulmonary infarction | Peripheral wedge-shaped consolidation with central lucencies |

Tumorous conditions such as invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma [4] (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4) and bronchus–associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [5] (Fig. 3.5) also occur with lobar consolidation.

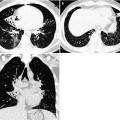

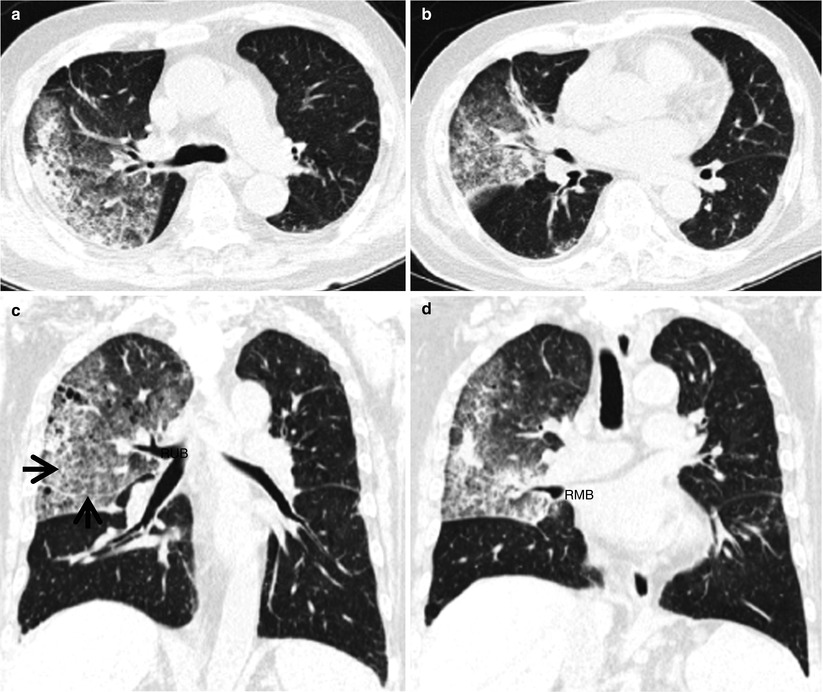

Fig. 3.3

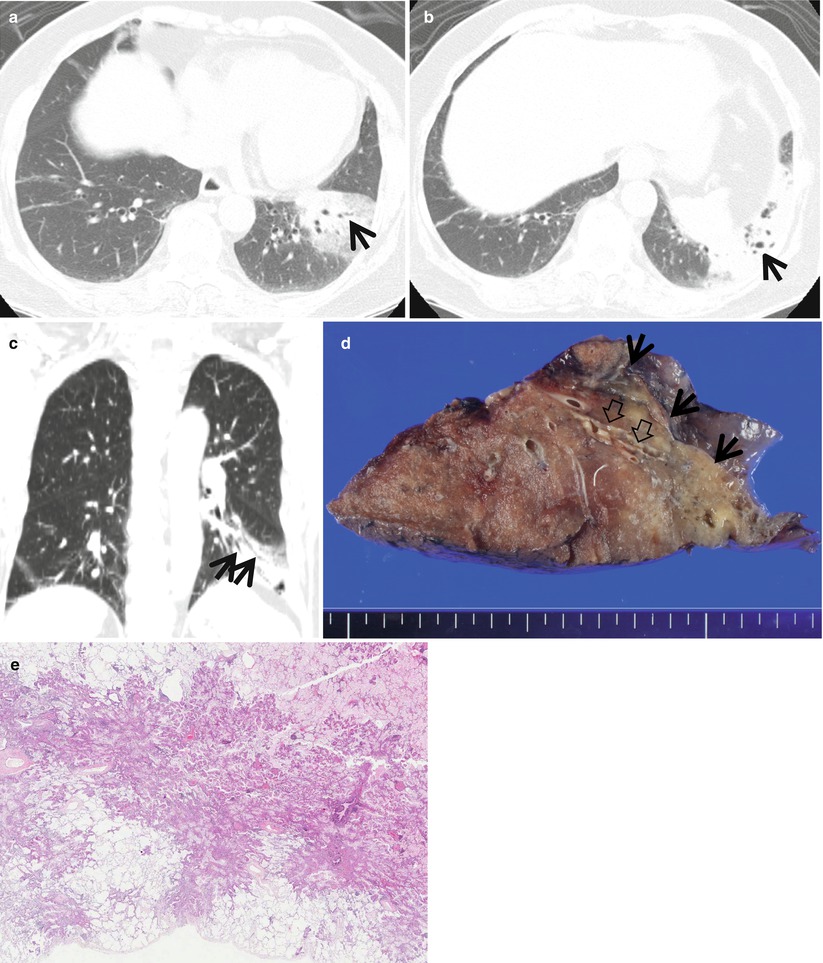

Lobar mucinous adenocarcinoma in a 75-year-old woman. (a, b) Transverse CT scans (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of liver (a) and splenic (b) domes, respectively, show non-segmental parenchymal consolidation and internal CT air-bronchogram signs (arrows) in the left lower lobe. Also note decreased lobar volume in the same lobe. (c) Coronal reformatted image shows parenchymal consolidation in the left lower lobe with CT air-bronchogram signs (arrows). (d) Gross pathologic specimen obtained with left lower lobectomy demonstrates a yellow-to-brown and somewhat myxoid tumor (arrows) in the left lower lobe. Also note the dilated bronchus with wall destruction (open arrows) within tumor. (e) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph shows lack of circumscribed border with permeative tumor spread to adjacent lung parenchyma. Alveolar spaces often contain mucin. Tumor has a distinctive appearance with neoplastic cells having a goblet or columnar morphology with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin

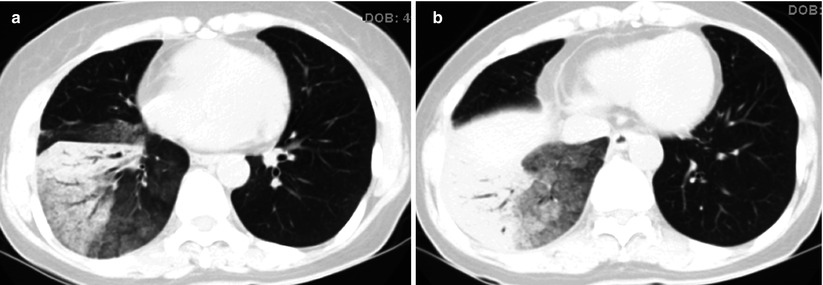

Fig. 3.4

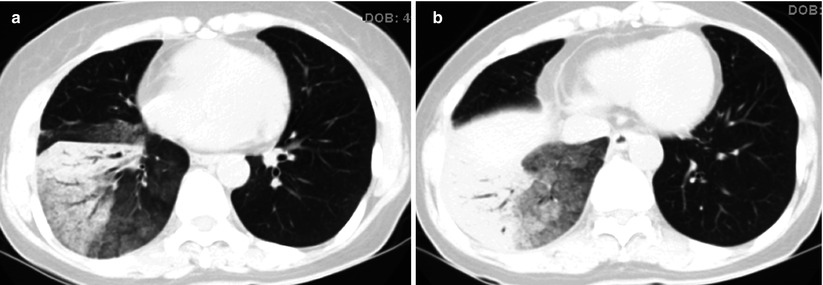

Diffuse adenocarcinoma in a 57-year-old woman. (a, b) CT scans (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of the basal segmental bronchi (a) and suprahepatic inferior vena cava (b), respectively, show parenchymal opacity (consolidation and ground-glass opacity) in the right lower lobe and in a portion of the right middle lobe. Also note CT air-bronchogram signs within lesions. Biopsy specimen obtained from the right lower lobe disclosed adenocarcinoma of moderate differentiation with tumor pleural invasion

The lobar consolidation may also be associated with obstructive pneumonia, cicatricial or passive atelectasis, and pulmonary infarction [6] (Fig. 3.6).

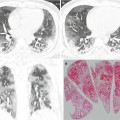

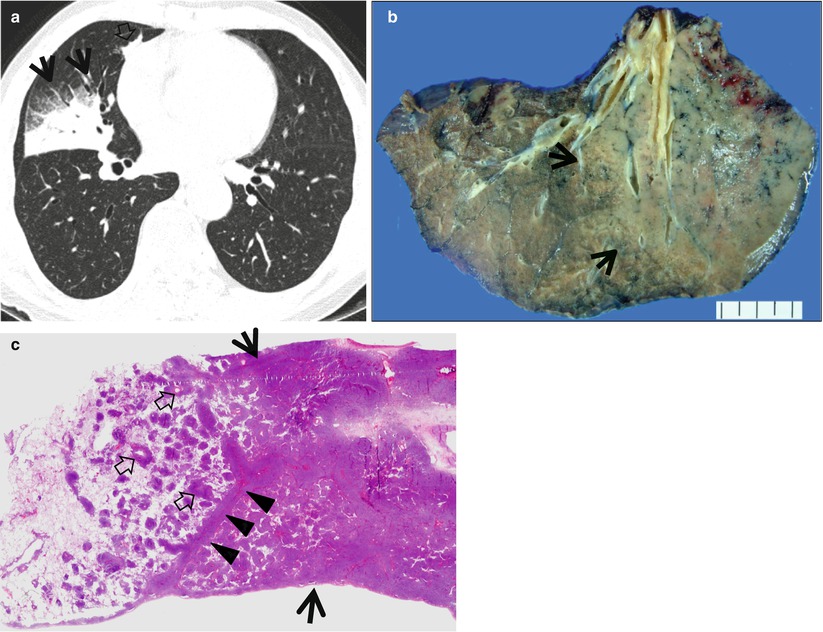

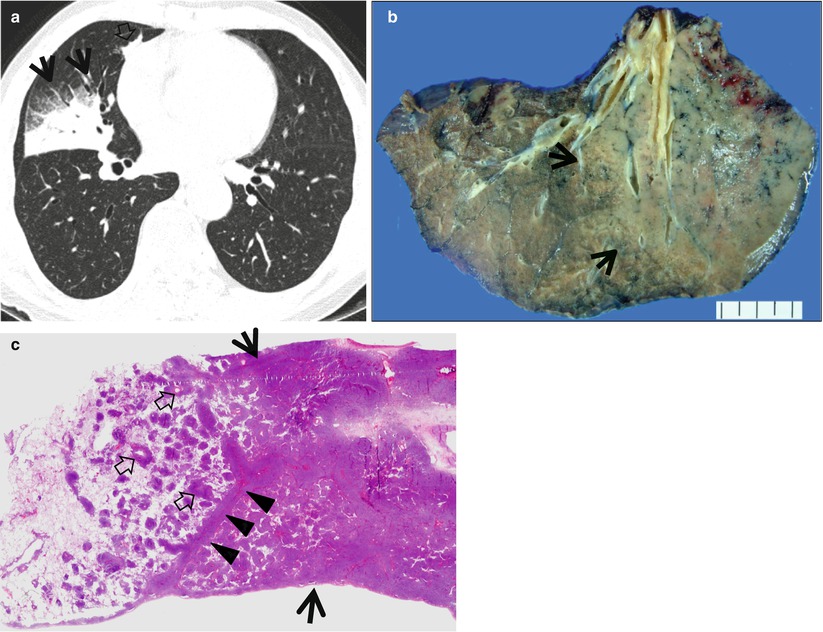

Fig. 3.5

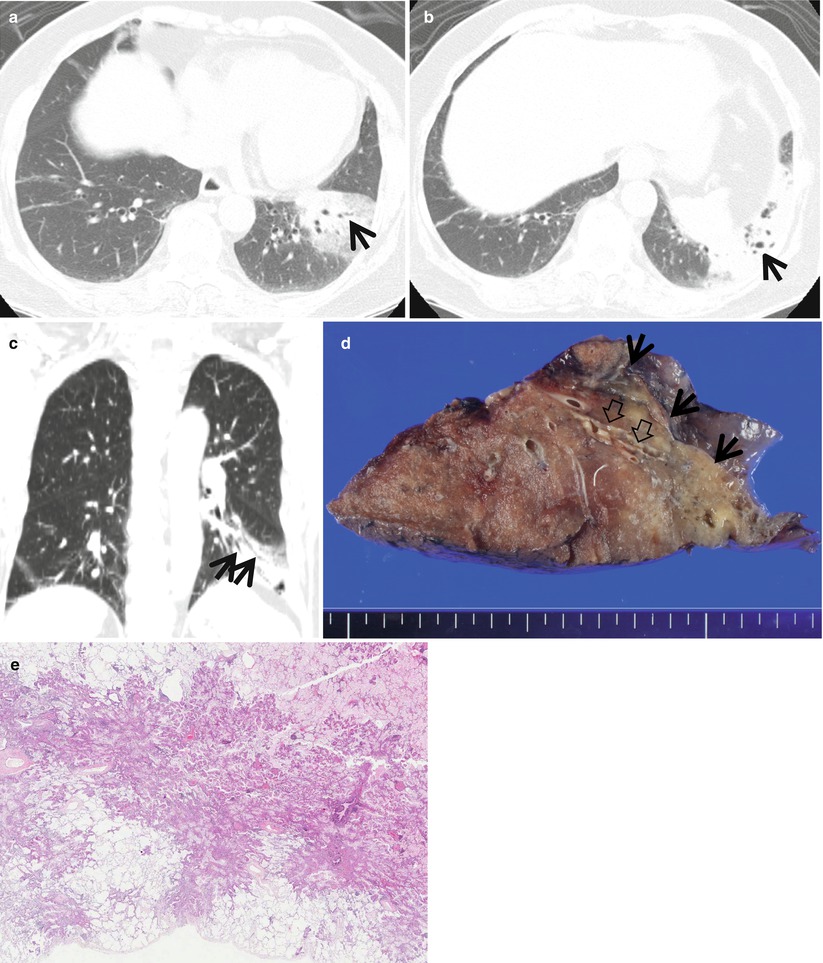

Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in a 60-year-old man. (a) Thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scan obtained at level of the inferior pulmonary veins shows parenchymal consolidation and ground-glass opacity (arrows) in lateral segment of the right middle lobe. Also note small rectangular consolidative lesion (open arrow) in medial segment of the same lobe. (b) Cut surface of gross pathologic specimen obtained with right middle lobectomy demonstrates ill-defined gray-tan consolidative lesion (arrows). Please note central solid area. (c) Low-magnification (×5) photomicrograph discloses tumor expansion from bronchovascular interstitium to alveolar space to form consolidative lesion (arrows) in the right half of specimen. In the left half, tumor cells are confined to bronchovascular interstitium only to appear as small centrilobular nodules (open arrows). Also note thickened interlobular septa and venules (arrowheads) with tumor cell infiltration

Distribution

Lobar consolidation in lobar pneumonia tends to be located at the middle and outer thirds of the lung. In contrast, atypical pneumonia frequently shows centrilobular nodules or acinar opacity and lobular consolidation or lobular ground-glass opacity and tends to be distributed at the inner third of the lung in addition to the middle and outer thirds [7].

Clinical Considerations

The presence of acute pneumonia symptoms and signs favors the diagnosis of lobar pneumonia. Also the rapid development of symptoms and signs may help diagnose acute lobar pneumonia.

MRI examination with ultrafast “water-sensitive” sequence depicts bright signal, the so-called MR white lung sign, from lung consolidative lesions in patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma [8].

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

1.

The presence of acute pneumonia symptoms and signs and their development speed help diagnose acute lobar pneumonia.

2.

Stretching, squeezing, and widening of the branching angle of CT air-bronchogram sign and bulging of the surrounding interlobar fissure suggest the diagnosis of lobar mucinous adenocarcinoma [4].

3.

Indolent and slow progressive nature of consolidative lesion may help make a diagnosis of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [5].

4.

Lobar Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Fibrinosuppurative consolidation of a large portion of a lobe, or of entire lobe, is the dominant characteristic of lobar pneumonia, while patchy consolidation defines bronchopneumonia. There are four stages of the inflammatory response: congestion (vascular engorgement, intra-alveolar fluid with few neutrophils), red hepatization (massive confluent exudation with neutrophils and red blood cells, filling alveolar spaces), gray hepatization (progressive disintegration of red blood cells), and resolution (organized by fibroblasts growing into it) [11].

Symptoms and Signs

Acute development of fever and purulent sputum is the classic manifestation of lobar pneumonia. Dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis may be present. Leukocytosis is often found, suggesting acute inflammatory process. In older debilitated or immunosuppressed patients, it may be mild or absent. Inspiratory crackle is heard on chest auscultation.

CT Findings

On CT, homogeneous airspace consolidation involving adjacent segments of a lobe is the predominant finding of lobar pneumonia [7] (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2). Areas of ground-glass attenuation can be seen adjacent to the airspace consolidation. The consolidation typically extends across lobular and segmental boundaries. Air bronchograms are usually seen.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Lobar pneumonia is characterized histologically by filling of alveolar airspaces by an exudate of edema fluid and neutrophils. This filling usually begins at the periphery of the lung adjacent to the visceral pleura and spreads via interalveolar pores and small airways centripetally, resulting in a homogeneous area of consolidation. Incomplete filling of alveoli can be seen as areas of ground-glass opacity. The bronchi remain filled with gas and become surrounded by the expanding inflammatory exudates and thus are often seen as air bronchograms on CT scans (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2).

Patient Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the severity of pneumonia. Pneumonia severity index (PSI) is a point scoring system to assess the risk of death due to pneumonia, including age, comorbid illnesses, physical examination findings, and laboratory findings [12]. CURB-65 is another useful scoring system [13]. Early adequate antibiotic administration and management stratification according to the scoring system are essential in the treatment of pneumonia.

Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly mucinous BAC) has a distinctive histologic appearance with tumor cells having a goblet or columnar cell morphology with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4). There is a strong tendency for multicentric, multilobar, and bilateral lung involvement, which may reflect aerogenous spread. They show frequent KRAS mutation [14].

Symptoms and Signs

Due to abundant mucin production of the cancer cells, patients with invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma can complain of copious amount of sputum, the so-called bronchorrhea. Otherwise, patients may be asymptomatic. As disease progresses to the bilateral lung, shortness of breath develops.

CT Findings

The CT findings of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma include consolidations, air bronchograms, and multifocal and sometimes multilobar solid and subsolid nodules or masses, which tend to be centrilobular or bronchocentric [15, 16]. Stretching, squeezing, and widening of the branching angle of CT air-bronchogram sign and bulging of the surrounding interlobar fissure may be helpful in the diagnosis of lobar mucinous adenocarcinoma [4] (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4). MRI white lung sign (bright high signal intensity on water-sensitive sequences) is also useful in the differential diagnosis between mucinous adenocarcinoma and infectious pneumonia [8].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

The CT features of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma showing airspace consolidation and air bronchograms are caused by tumor growth along the alveolar wall (lepidic growth) combined with secretion of mucin [17, 18] (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4). As the tumor fills the alveolar spaces and infiltrates the alveolar septa and bronchial walls, the bronchus becomes stretched, squeezed, and rigid [4]. Production of mucin may result in expansion of the lobe, leading to bulging of interlobar fissures. MRI white lung sign is related to the high intratumoral content of mucin.

Patient Prognosis

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma has a strong tendency for multifocal, multilobar, and bilateral lung involvement, which may reflect aerogenous spread. Even if surgically resected in the localized stage, it frequently recurs in the remaining lung. Mucinous adenocarcinoma is essentially insensitive to EGFR-targeted therapy [19]. The overall prognosis for patients with invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma is worse than for those with the nonmucinous adenocarcinoma.

Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (BALT) Lymphoma

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Pulmonary marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) is an extranodal lymphoma, which is thought to arise in acquired BALT secondary to inflammatory or autoimmune processes. The neoplastic cells infiltrate the bronchiolar epithelium, forming lymphoepithelial lesion. They typically show a yellow-gray consolidative mass and appear as diffuse infiltrate of small lymphoid cells [5] (Fig. 3.5).

Symptoms and Signs

In BALT lymphoma of lobar consolidation type, constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, night sweating, and fever are more common than respiratory symptoms. Chronic cough and dyspnea are the main respiratory symptoms.

CT Findings

The main CT findings of BALT lymphoma are airspace consolidation or nodules containing air bronchograms within the lesions [5]. The lesions are usually multiple and bilateral (Fig. 3.5). Other findings include single nodule (also note section “Solitary Pulmonary Nodule (SPN), Solid” in Chap. 1), bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis, and diffuse interstitial lung disease pattern. Indolent and slow progressive nature of consolidative lesion may help make a diagnosis of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

CT findings of BALT lymphoma showing solitary or multifocal nodules or masses and areas of airspace consolidation are related to proliferation of tumor cells within the interstitium such that the alveolar airspaces and transitional airways are obliterated [20] (Fig. 3.5). Because the bronchi and membranous bronchioles tend to be unaffected, an air bronchogram is common. Interlobular septal thickening, centrilobular nodules, and bronchial wall thickening on CT images are related to perilymphatic interstitial infiltration of tumor cells.

Patient Prognosis

BALT lymphoma shows the indolent clinical course. The estimated 5- and 10-year overall survival rates have been reported to be 90 and 72 %, respectively [21]. Age and performance status are the prognostic factors.

Pulmonary Infarction

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Infarction in the lungs is generally wedge-shaped and commonly multiple. An occluded pulmonary artery is found at the apex of the infarct; the base of the infarct is on the pleura. Any part of the lung may be affected but infarction is most common at the lung bases. It is classically hemorrhagic and appears as a red-blue area in early stage and becomes paler and red-brown due to hemosiderin deposition. With passage of time, fibrinous replacement begins and eventually converts the infarct into contracted scar. In thromboembolism, alternatively, the embolus may result in pulmonary infarction, which is indicated clinically by an attack of localized pleural pain, dyspnea, and hemoptysis. Often there is more than one embolic episode [11].

Symptoms and Signs

Acute development of more severe dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and blood-tinged sputum are the cardinal symptoms of pulmonary infarction. Purulent sputum is absent. Tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxia are found. Lower leg swelling and positive Homan’s sign can be detected, reflecting deep venous thrombosis.

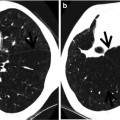

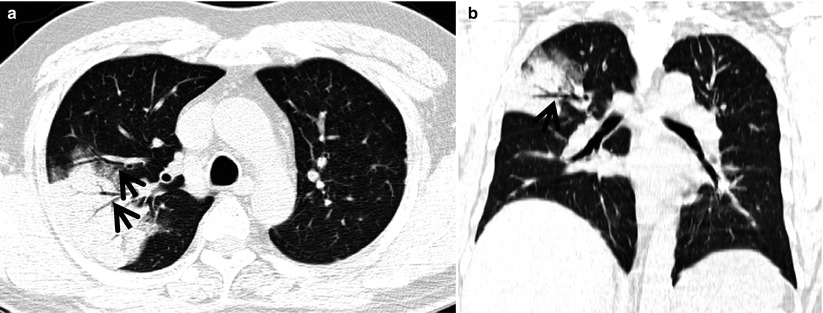

CT Findings

A peripheral wedge-shaped area of consolidation on CT is suggestive of pulmonary infarction [22]. Internal morphologic characteristics of this consolidation include the presence of central lucencies and the absence of air bronchograms [9] (Fig. 3.6). A slight and continuous FDG uptake at the border of a peripheral lung consolidation (rim sign) can be seen at FDG PET–CT [23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree