, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

Consolidation refers to an area of homogeneous increase in lung parenchymal attenuation that obscures the margins of vessels and airway walls [1]. Air bronchograms may be present with consolidative area. Pathologically, consolidation represents an exudate or other product of disease that replaces alveolar air, rendering the lung solid [2, 3].

Consolidation with Subpleural or Patchy Distribution

Definition

Consolidation refers to an area of homogeneous increase in lung parenchymal attenuation that obscures the margins of vessels and airway walls [1]. Air bronchograms may be present with consolidative area. Pathologically, consolidation represents an exudate or other product of disease that replaces alveolar air, rendering the lung solid [2, 3].

Diseases Causing the Pattern

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) (Fig. 22.1), chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) (Fig. 22.2), Churg–Strauss syndrome (CSS) (Fig. 22.3), and radiation pneumonitis (Fig. 22.4) usually depict subpleural or patchy areas of consolidation in both lungs.

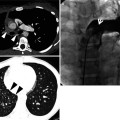

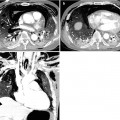

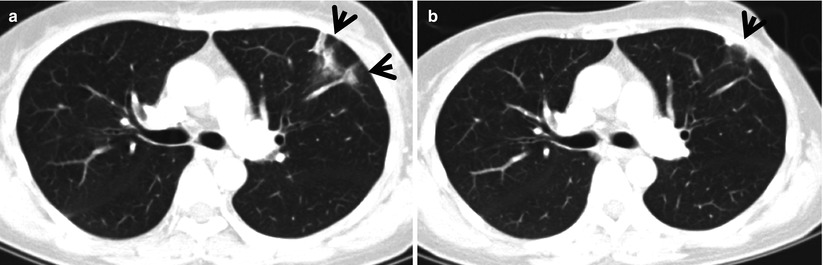

Fig. 22.1

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia in a 44-year-old woman. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of distal main bronchi (a) and inferior pulmonary veins (b), respectively, show patchy areas of consolidation, ground-glass opacity, or ground-glass opacity nodules in both lungs. Lung lesions show typically peribronchovascular or subpleural distribution. (c) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) also demonstrates same pattern of lung abnormalities distributed along bronchovascular bundles. (d) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen obtained from right middle lobe shows alveolar-filling process with inflammation (arrows) and fibrinous exudate (open arrows). (e) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph discloses granulation plugs (arrows) filling alveolar spaces and alveolar ducts. Patient also has histopathologically some component of capillaritis and alveolar hemorrhage

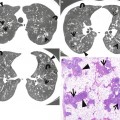

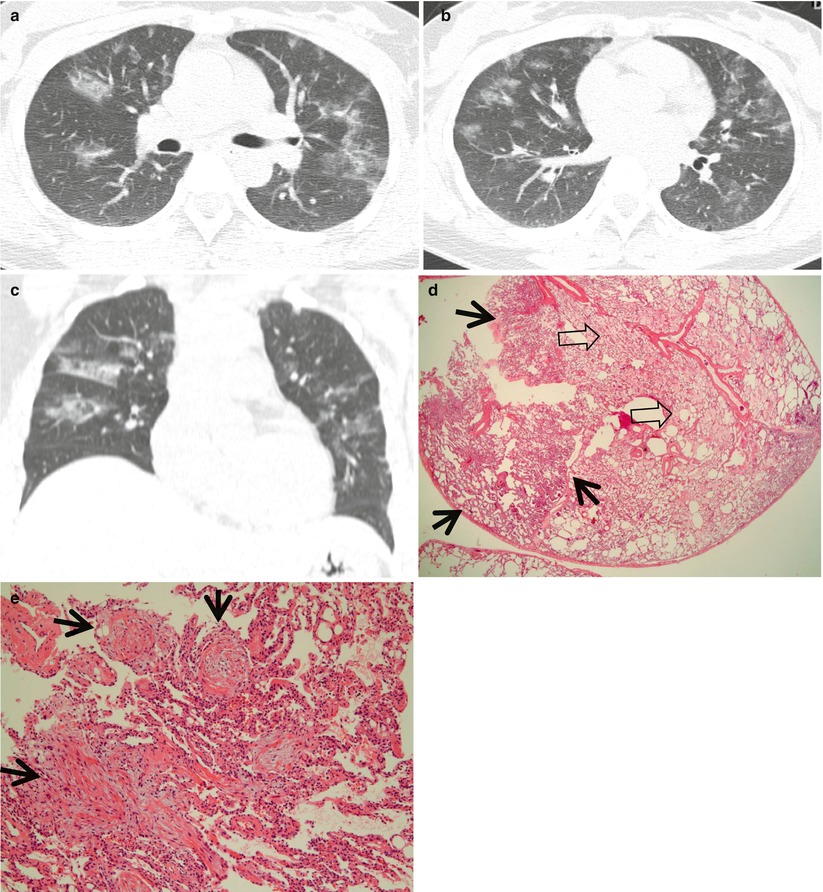

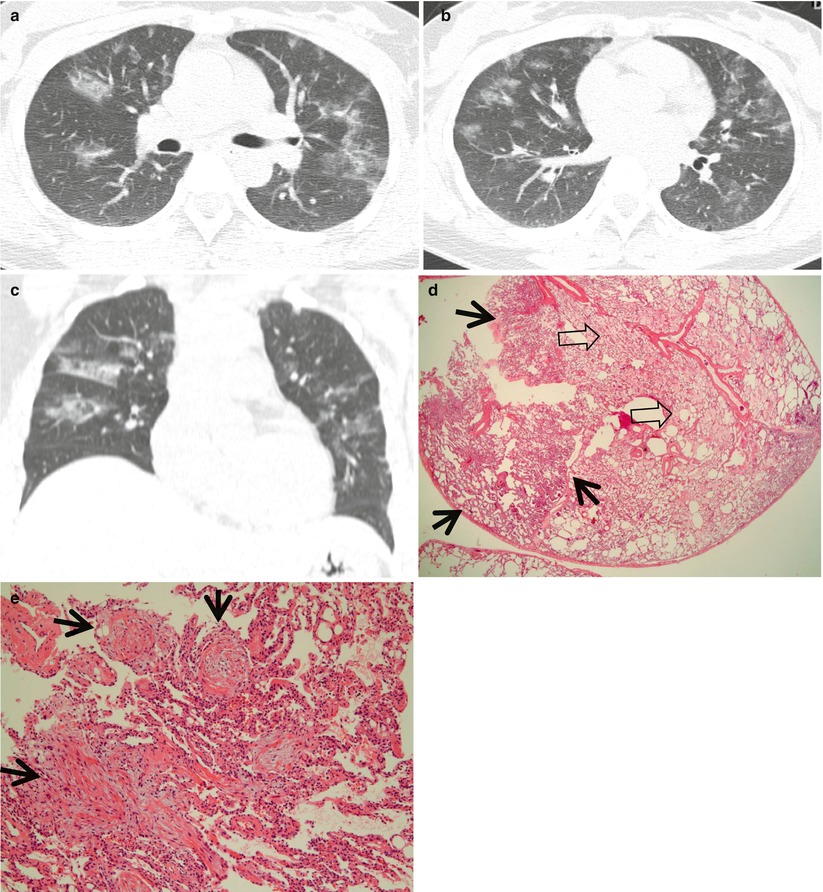

Fig. 22.2

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia in a 55-year-old asthmatic woman. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (1.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of aortic (a) and azygos (b) arches, respectively, show patchy areas of consolidation and ground-glass opacity in both lungs

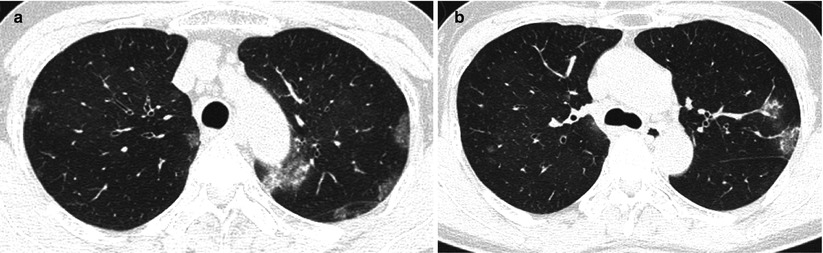

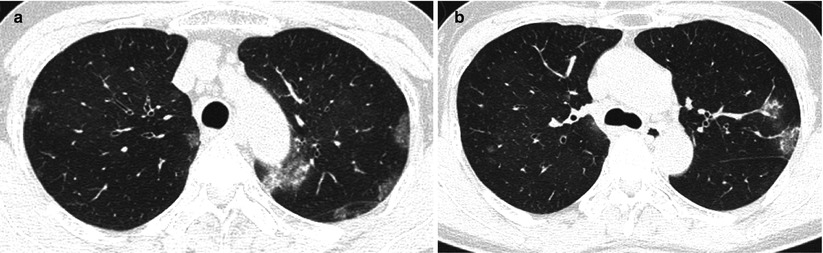

Fig. 22.3

Churg–Strauss syndrome in a 39-year-old asthmatic man. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and cardiac ventricle (b), respectively, show patchy and extensive areas of consolidation in both lungs. Also note some areas of ground-glass opacity (arrows) and poorly defined nodules (arrowheads). (c) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen obtained from right upper lobe demonstrates alveolar-filling process with eosinophils (arrows). (d) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph discloses alveolar spaces filled with eosinophils (eosinophilic pneumonia) (arrows). In other areas, small extravascular granulomas and few areas of capillaritis were seen (not shown here)

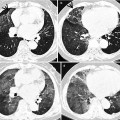

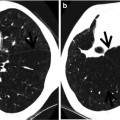

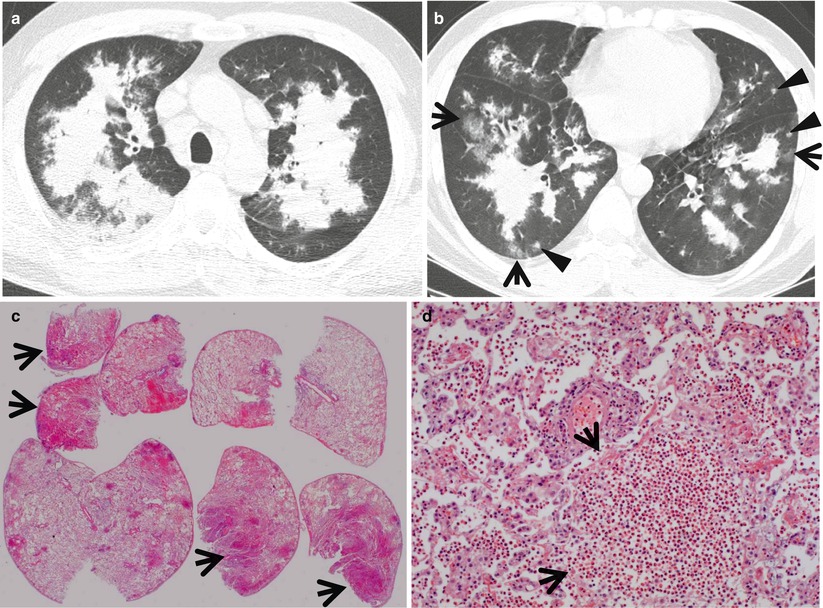

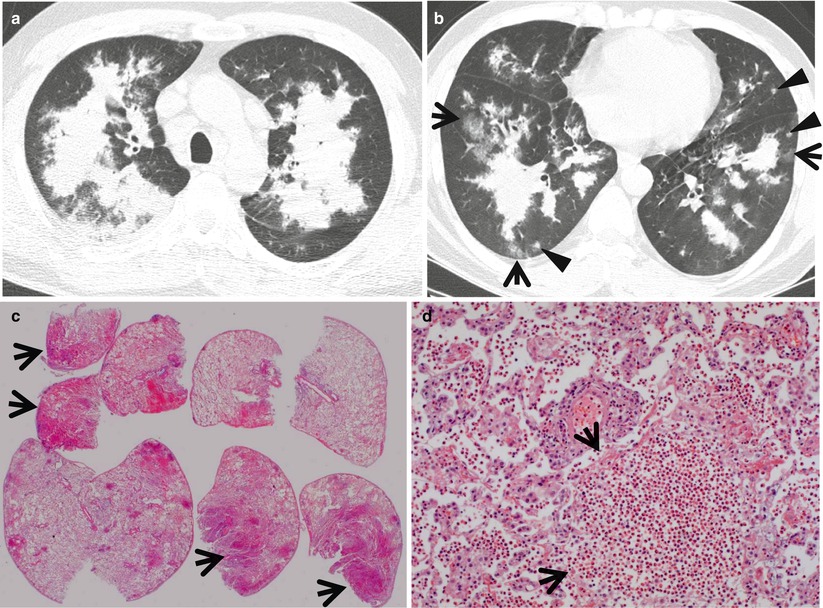

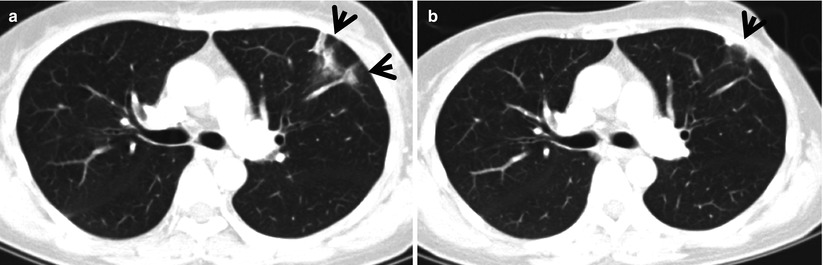

Fig. 22.4

Radiation pneumonitis in a 44-year-old woman with left breast cancer. (a, b) Lung window images of consecutive CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at level of right upper lobar bronchus show focal parenchymal consolidation (arrows) in anterior segment of left upper lobe. Patient received conformational irradiation after partial left mastectomy

Distribution

Consolidation in COP is present alone or as part of a mixed pattern and has a predominantly subpleural or peribronchovascular distribution [4]. The consolidation usually involves both lungs and shows middle and lower lung zone predominance [5, 6]. In CEP, CT scans show subpleural consolidation with upper and middle lung zone predominance [7]. Consolidation in CSS is present, usually mixed with other patterns of abnormalities including small nodules and ground-glass opacity (GGO), and shows random distribution [8]. Consolidation in radiation pneumonitis involves uniformly the irradiated lung portion, but not necessarily conforming to the shape of the irradiation portal [9]. The consolidation may show patchy and extensive distribution.

Clinical Considerations

The presence of asthma history suggests the diagnosis of chronic eosinophilic lung disease (almost all patients in CSS and approximately 40 % of patients with CEP) [10]. COP or COP-like lung lesion may be seen in collagen vascular disease, occupational lung disease, or drug-induced lung disease. Abnormal lung lesions like consolidation occur equally in irradiated and unirradiated lung in radiation pneumonitis. This fact, along with prompt improvement of the lesions after corticosteroid therapy, suggests an immunologically mediated mechanism such as a hypersensitivity pneumonitis [11].

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

Diseases | Distribution | Clinical presentations | Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zones | ||||||||||||

U | M | L | SP | C | R | BV | R | Acute | Subacute | Chronic | ||

COP | + | + | + | + | + | + | Nodules, reversed halo sign | |||||

CEP | + | + | + | + | + | + | Asthma in 40 % of patients | |||||

CSS | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Asthma in all patients, airway disease components | ||||

Radiation pneumonitis | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Usually irradiated region; consolidation beyond irradiated field, hypersensitivity pneumonitis? | ||||

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

COP is characterized by variably dense airspace aggregates of fibroblasts in immature collagen matrix. This alveolar-filling process can be seen to extend into or from terminal bronchioles. Typically, the lung architecture is preserved in COP, and lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes are present in variable numbers within the interstitium (Fig. 22.1). Fibrin may be seen focally in association with airspace organization. Alveolar macrophage accumulation may be present, attesting to some degree of airway obstruction. Interstitial fibrosis and honeycomb lung remodeling are not components of the cryptogenic (idiopathic) form of organizing pneumonia [12].

Symptoms and Signs

The initial manifestations are nonspecific, with a flu-like illness of fever, malaise, and cough [13]. It is followed by progressive and usually mild dyspnea. Dyspnea may occasionally be severe. In most cases, the duration of onset is less than 3 months. The disease is frequently misdiagnosed as infectious pneumonia. Hemoptysis, chest pain, and night sweating are rare. Finger clubbing is absent. Bibasilar inspiratory crackles are observed at auscultation.

CT Findings

The characteristic HRCT finding of COP consists of unilateral or bilateral areas of airspace consolidation with subpleural or peribronchial distribution [4, 14] (Fig. 22.1). An air bronchogram with bronchial dilatation may be seen in patients who have extensive consolidation, and air bronchograms are usually restricted to these consolidative areas. GGOs are commonly present in association with the areas of consolidation. Curvilinear opacity with an arcade-like appearance (perilobular pattern) is seen in more than half of the patients [15]. Small, ill-defined nodules, often in a centrilobular distribution, are seen in 30–50 % of cases. Occasionally, the disease is manifested as a large nodule or mass-like area of consolidation. Sometimes, COP shows a reversed halo sign, which is defined as central GGO surrounded by more dense airspace consolidation with crescent and ring shapes [5].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

The areas of consolidation correspond histologically to the regions of lung parenchyma that show organizing pneumonia: granulation plugs lying within small airways, alveolar ducts, and alveoli [16] (Fig. 22.1). The GGO correlates with areas of alveolar septal inflammation and minimal airspace fibrosis. The small nodules are related to foci of organizing pneumonia limited to the peribronchial region or to fibroblastic tissue plugs within the bronchiolar lumen. Perilobular pattern pathologically reflects the area of organizing exudate accumulation in the perilobular alveoli, with or without interlobular septal thickening [15]. Reversed halo sign correspond to central area of alveolar septal inflammation and peripheral area of organizing pneumonia within the alveolar ducts [5].

Patient Prognosis

COP responds well to corticosteroids. Corticosteroids result in dramatic clinical improvement, with regression of symptoms within days. The overall prognosis is excellent. Spontaneous improvement over 3–6 months has been reported. Relapse occurs in 13–58 % of patients on decreasing or after stopping corticosteroid therapy.

Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Microscopically, eosinophils fill the alveoli and infiltrate the interstitium (Fig. 22.2). The alveoli also contain a variable number of macrophages. The eosinophil infiltrate may involve small blood vessels but necrotizing vasculitis is not encountered: its presence would suggest Churg–Strauss allergic granulomatosis [17].

Symptoms and Signs

Cough and dyspnea are invariably present [18]. The severity of dyspnea is highly variable from one case to another. Wheezing occurs in about half of the case. Chest pain and hemoptysis are rare. The symptoms are most often present for at least 1 month before diagnosis is made. Weight loss, night sweating, and fever are frequent. The most common extrathoracic manifestations are cardiac, including chest pain with ST segment changes or associated pericarditis.

CT Findings

The characteristic CT finding of CEP is non-segmental areas of airspace consolidation and GGO with peripheral predominance [19, 20] (Fig. 22.2). The consolidation and GGO usually have upper lobe predominance. Less common findings include crazy-paving pattern, nodules, and reticulation. These less common findings predominate in the later stages of CEP. CT performed more than 2 months after the onset of symptoms shows linear band-like areas of parenchymal opacity parallel to the pleural surface. Pleural effusion is observed in less than 10 % of cases.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Areas of consolidation on HRCT correspond histologically to accumulations of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the alveoli and interstitium and interstitial fibrosis (Fig.22.2).

Patient Prognosis

All the reports have confirmed the dramatic response to corticosteroids. Symptoms and pulmonary infiltrates on imaging improve within a few days of initiation of corticosteroid therapy. However, relapses are observed in up to 50 % of patients while tapering or after stopping the doses of corticosteroids. Long-term corticosteroid therapy is required in more than 50 % of the cases.

Churg–Strauss Syndrome

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The findings on lung biopsy depend on the stage of the disease during which the biopsy is obtained and whether or not the patient has received therapy, particularly steroids. Lung biopsies from CSS patients in the full blown vasculitic phase may show asthmatic bronchitis, eosinophilic pneumonia, extravascular stellate granulomas, and vasculitis (Fig. 22.3). Vasculitis can affect arteries, veins, or capillaries. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage and capillaritis can be seen [21].

Symptoms and Signs

Mean age of onset is 38 years. Asthma is essentially universal in CSS [22]. Virtually all patients have eosinophilia. Cardiac involvement is relatively common and is a major cause of mortality. Compared with ANCA-associated granulomatous vasculitis and microscopic polyangiitis, peripheral nerve involvement is more common while pulmonary hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis are much less common.

CT Findings

The most common HRCT findings consist of small centrilobular nodules, GGO, consolidation in a patchy or a predominantly subpleural distribution, bronchial wall thickening and dilatation, interlobular septal thickening, and a mosaic perfusion pattern [8] (Fig. 22.3). Unilateral or bilateral pleural effusion is seen in up to 50 % of patients.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Small nodules histopathologically correlate with areas of dense eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration in the bronchiolar walls and patchy areas of capillaritis in alveolar walls. The areas of consolidation correspond histopathologically to the area of eosinophilic or granulomatous inflammation predominantly in the alveoli and alveolar walls. Interlobular septal thickening may be caused by septal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and mild fibrosis [8, 23].

Patient Prognosis

Systemic corticosteroids remain the mainstay of therapy. Cyclophosphamide can be used in combination with corticosteroids in cases with severe disease. The mortality rates attributable to CSS or complications of therapy are less than 10–20 %. Older age, azotemia, and cardiac involvement are poor prognostic factors.

Radiation Pneumonitis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree