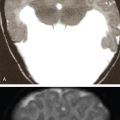

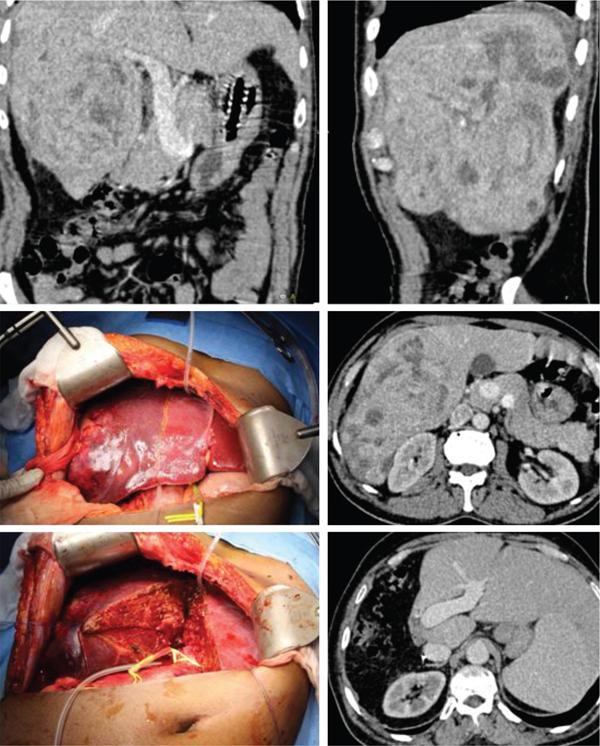

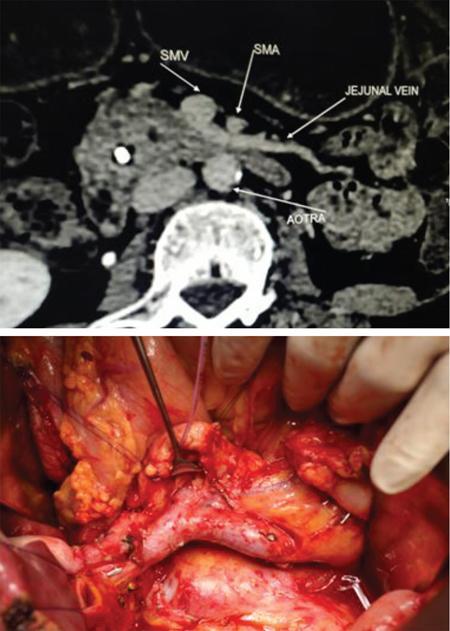

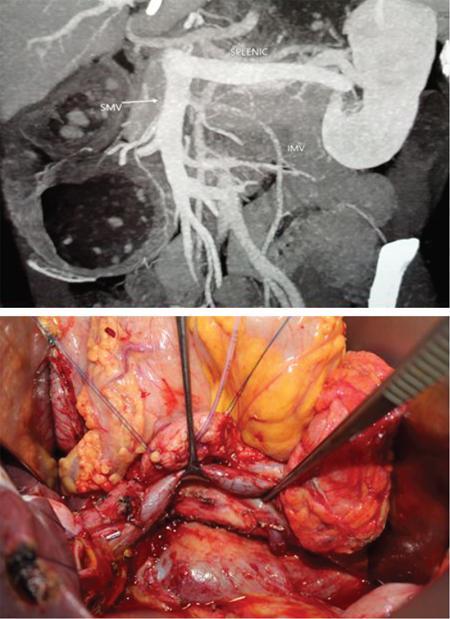

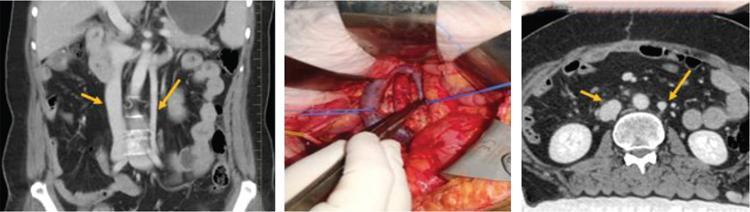

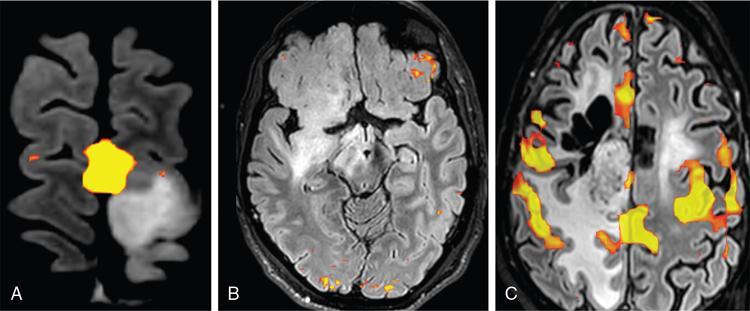

Naveen Padmanabhan, Bagyam Raghavan, Adhithyan Rajendran, Abubacker Sulaiman, Roopesh Kumar, Arunkumar Karthikayan Our Goal can only be reached through the vehicle of a plan. Pablo Picasso Radiology plays a vital role in staging and planning of surgery in gastrointestinal malignancies. Imaging aids in avoiding non-therapeutic laparotomies, choosing the optimal surgical approach and decreasing the morbidity of surgery. Most surgeons prefer computerized tomography (CT) images for staging and surgical planning. However, we have an array of imaging modalities to complement and supplement CT scans. A surgeon looks for the following in the imaging and reporting before operating upon the patient with GI cancers: Almost all guidelines (AJCC, NCCN and ESMO) recommend a CECT of abdomen, pelvis and chest for staging of majority of abdominal malignancies (oesophagus to rectum). Due to its wide spread availability and ease in reading, most surgeons prefer CECT over other imaging modality. Usually all the malignancies are supplemented by endoscopy finding as most of them are malignancies in luminal organs like stomach, oesophagus and colon. Early lesions limited to the mucosa and sub-mucosa of the organs are sometimes missed in CT imaging and can be identified only in endoscopy. However, in most cases, the patient presents to doctor only after the symptoms have arised and in those cases the lesions are obvious in CT scans. In oesophagus and stomach cancers CECT is accurate in determining the invasion to other organs which helps in deciding the management. In this section, we will discuss certain important findings the surgeon looks for in each malignancy. A synoptic reporting with inclusion of these imaging findings shall be of greater use in surgical planning. In CECT of chest and abdomen, surgeon looks for location of the tumour and extent of the tumour. Most colonic cancers are adequately staged with CT scans and surgeons look mainly for any signs of local invasion and liver metastasis. Although rare, nodal disease around the SMA should be identified. Synchronous lesions also need to be looked upon as it necessitates an extended resection like extended hemicolectomy, total colectomy as against formal right and left colectomies. The most important feature that is examined in rectal cancers is the invasion of mesorectum. MRI is superior in identifying the mesorectal integrity and invasion. In males invasion of seminal vesicles and prostate is looked and in females vaginal and uterine infiltration is looked upon. Liver cancers mostly originate in the background of liver cirrhosis and presence of the same should be identified. Patient undergoing major liver resection can survive with future liver remnant of 20%–30% (FLR). However, in post-chemotherapy or in cirrhotic states, the FLR should be greater than 40%–50%. Also in cirrhotic states there are multiple portal collaterals in areas of porto-venous communications which can add to the complexity and difficulty of surgery. HCCs are notorious for synchronous lesions and vascular invasion both of which should be identified pre-operatively. As mentioned previously, hepatic vasculature can have a variety of anomalies which needs to be identified pre-operatively in imaging. CECT with pancreatic protocol is very critical in staging and surgical planning for pancreatic cancers. The surgeon is particularly interested in local invasion of surrounding vessels to assess the resectability. SMV and PV invasion are considered borderline resectable and SMA invasion is considered unresectable. When the patient has jaundice >10–15 mg/dL, many surgeons routinely perform elective biliary stenting to reduce complications from jaundice. We need to assess whether the intra-hepatic biliary radicles and bile duct are sufficiently dilated to allow the safe performance of percutaneous or endoscopic drainage. Minimally invasive technologies with laparoscope and robotic platforms have been extensively studied and now approved for the management of many thoracic and abdominal malignancies. Level 1 evidence is available for laparoscopic resection of colon cancer and rectal cancers. Increasingly many centres have been utilizing robotic and laparoscopy for gastric, hepatic and pancreatic resections also. The discussion of indications of minimally invasive technology in specific tumours is beyond the scope of this book. Laparoscopy has been extensively used in patients with dubious radiological findings or to assess specific scenarios where the imaging is not specific. However, certain tumours where the resectability is assessed upon whether lesion is invading the vessel or not, such as hepatic artery invasion in HCC or SMA invasion in pancreatic cancers can more definitely assessed with CT images than laparoscopy. These areas are difficult to access with laparoscopy by most surgeons. A 54-year-old patient had been diagnosed with liver mass in ultrasound and his AFP levels were elevated. A proper triple CT was done and the image shows an exophytic lesion involving the segment 6 and 7. Although technically the lesion could have been resected with right hepatectomy, there was a considerable risk of tumour spillage which could adversely affect the prognosis. Hence, trans arterial chemoembolization was done to down size the tumour and a successful right hepatectomy without compromising the margins was done 6 weeks after TACE (Fig. 1.33.1). Routine performance of CT angiogram with three-dimensional reconstruction of the vascular anatomy is critical for safe and efficient performance of a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Particular attention is paid to hepatic arteries, inferior mesenteric vessels and first jejunal vein. During the dissection around SMV and SMA the origin and drainage of IMV and jejunal vein are visually preserved. In patients where the anterior jejunal vein crosses anterior to SMA to drain into SMV the dissection around uncinate will be technically difficult. IMV routinely drains into the splenic vein, whereas in some cases it drains into SMV which is not to inadvertently ligated (Figs. 1.33.2 and 1.33.3). 46-year-old lady had recurrent carcinoma ovary with recurrence in para-aortic and para-caval nodal basins. She was earlier operated before 2 years with hysterectomy, omentectomy and peritonectomy. She had recurrence in RP nodal basin and was treated with four cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. While planning for surgery with CT angiogram, note was made of accessory inferior vena cava. This was visualized and preserved intra-operatively. An accessory vein in the retroperitoneum could have been mistaken for gonadal or any other inconsequential vein. With prior knowledge of accessory IVC, care was taken to preserve it and remove all the nodal and fibrofatty tissue around IVC (Fig. 1.33.4). There are innumerable number of scenarios where radiology has altered the course of management in the patient and hence plays a vital role in the management of the patient. Close coordination between the radiologist and surgical team is necessary to optimize the reporting. Radiologist should follow up the patient and surgeon to recognize the accuracy of reporting. Advances in neuroanesthesia, neuromonitoring and neurosurgical techniques have given birth to the concept of awake surgeries. Traditional teaching advocates the resection of gliomas until the contrast or FLAIR border in the preoperative MRI. Supratotal removal of gliomas have been advocated recently to improve the patient outcome and also to help in delaying the malignant transformation of the tumour in the future. On a meta-analysis of over 8000 supratentorial gliomas, it was found that Intra-operative Stimulation brain Mapping (ISM) is associated with decreased late neurological deficits in the late post-operative period despite a radical resection of the intra-axial tumour. Based on the above findings, Hamer et al suggested the use of ISM as a standard of care in all glioma surgeries. The success of awake craniotomy lies in the coordinated effort of a motivated and cooperative patient, an expert neuroanesthetist, neuropsychologist and a team of experienced neurosurgeons. The asleep–awake–asleep paradigm is popular and has more patient compliance. Intravenous propofol is given at the time of Foley catheterization which is followed by Mayfield pin application. Bupivacaine/Lidocaine is administered along the pin sites and the line of incision for local anesthesia. According to the craniotomy planned, a local scalp block is given. A combined infusion of propofol and remifentanil, calculated according to the weight of the patient, is given right before placing the incision on the skin and is continued until craniotomy is completed. Dura is infiltrated with local anaesthetic using a small 30 G needle. When the patient is awakened, there might be coughing which might cause brain herniation. In order to prevent such a complication, the infusion is discontinued before the dura is opened. During sensorimotor mapping, ice cold Ringer lactate solution should be kept readily available to abort seizures in case they arise. Awake craniotomies are fascinating in a way that the patient converses with the surgeon as he removes the tumour providing him constant reassurance about the integrity of the tracts and the absence of neurological deficits. Musicians or singers are even made to play their instrument or sing along during surgery to prevent deficits which even if minor in common parlance might be significant enough to destroy their careers. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become one of the most commonly used modalities of functional imaging in clinical and research work. The scientific principle behind fMRI lies in the fact that oxyhemoglobin is more diamagnetic, whereas deoxyhemoglobin is more paramagnetic. The former is found relatively in higher concentrations in the active regions of the brain due to increased blood flow. Motor (leg, hand, lips, Fig. 1.33.5A) and language cortices (Fig. 1.33.5B) are usually accurately mapped by fMRI. Resting state fMRI (Fig. 1.33.5C), which is a task-free functional study, is a new promising approach to map the eloquent regions including the motor areas, especially in those not able to perform the task-based fMRI (Fig. 1.33.6).

1.33: CT and MRI in surgical planning and intra-operative imaging

Gastrointestinal

Role of contrast-enhanced CT scan in GI malignancies

Oesophageal cancer

Stomach cancers

Colonic cancers

Rectal cancers

Hepatocellular cancers

Pancreatic cancers

Role of minimally invasive modalities as an adjunct to radiology

Case vignettes where radiology played a critical role in intra-op management of abdominal malignancies

Peri ampullary cancers

Double IVC in retroperitoneal nodal dissection

Conclusions

Neurological

Awake surgeries

Functional imaging

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree