Key Points

- ▪

Although stents are easy to visualize by cardiac CT (CCT), their lumen is difficult to assess. The assessment of patency or restenosis of coronary stents is a challenge for CCT angiography, but one that is increasingly being met.

- ▪

Assessment of larger stented arteries is far more successful than that of smaller stented arteries.

- ▪

The potential “blooming” artifacts from the metal mesh of coronary stents is greatly compounded by motion.

- ▪

Use of different “windowing” and filters is needed to minimize the intrusion of blooming artifact.

- ▪

Background atherosclerotic coronary artery calcification only compounds stented coronary artery assessment.

- ▪

In larger stents with better imaging, visualization of the lumen is feasible, but in smaller stents and in lower-quality studies, luminal assessment is still challenging. Hence, a priori knowledge of the stent size and its location should be obtained to ascertain whether coronary computed tomographic angiography has a reasonable chance of imaging the stented artery accurately.

- ▪

Stent gaps and stent fracture are well imaged by CCT, as is stent overhang into the left main coronary artery.

CCT Imaging of Coronary Stents

The accurate assessment of coronary stents remains a major challenge for cardiac CT (CCT), and although the stent itself is readily imaged, the lumen within it is not, because the stent material confers “blooming” artifact. Stents with a denser “weave” are harder to image. A stent deployed within a stent for restenosis leaves little chance of accurately depicting the lumen. Small amounts of motion during acquisition disperse the partial volume averaging effect over more voxels, increasing the depiction of the stent and further reducing the luminal depiction. Thicker struts confer greater artifact. As would be expected, the patency of large vessels or stents is easier to assess, as the blooming artifact is less likely to obscure the whole lumen. False positives occur in 5% to 10% of cases, reducing the positive predictive value. Bifurcation lesions are difficult to assess. Although CCT and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) data generally correlate, CCT tends to overestimate stent diameter. Only studies that are either small, single-center, or select have been presented thus far, and almost always of stents of 2.5 mm or larger, which remains the lower limit of reasonable size to assess by CCT. Few series have been published with 64-CCT systems. The generally pessimistic data that were obtained in studies of older systems, such as those using 16-CCT, still are considered the norm, so that it is still thought that, in most cases, the presence or absence or extent of in-stent restenosis cannot be determined ( Tables 7-1 through 7-3 ).

| AUTHOR | JOURNAL | YEAR | CT | NO. PATIENTS/ STENTS | NONASSESS. (%) | Lesion | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity For ISR (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schuijf et al. | Am J Cardiol | 2004 | 16 | 22 | 1 | 78 | 100 | — | — | |

| Van Mieghem et al. | Circ | 2007 | — | — | — | 70 LMCA only | 100 | 91 | 67 | 100 |

| Cademartiri et al. | JACC | 2007 | 64 | 182 | 7% | 192 stents all ≥2.5 mm | 95 | 93 | 63 | 99 |

| Gaspar et al. | JACC | 2005 | 40 | 65 | — | 72 | 93 | 65 | 95 | |

| Oncel et al. | Radiol | 2007 | — | 30/39 | 0 | 89 | 95 | 94 | 90 | |

| Oncel et al. | Am J Radiol | 2008 | Dual source | 30/39 | — | Stenosis and occlusion | 100 | 94 | 89 | 100 |

| Pugliese et al. | Heart | 2008 | — | 100/178 | 5 | 94 | 92 | 77 | 98 | |

| Ehara et al. | JACC | 2007 | — | 81/125 | 12 | 91 | 93 | 77 | 98 | |

| Rixe et al. | Eur Heart J | 2006 | 64 | 64/102 | 42% | 86 | 98 | 86 | 98 | |

| Rist et al. | Acad Radiol | 2006 | 64 | 75 | 8% | 75 | 92 | 67 | 94 | |

| Abdelkarim et al. | JCCT | 2010 | 64 | 55/122 | 4% | 91 | 95 | 96 | 91 |

| AUTHOR | JOURNAL | YEAR | CT | NO. PATIENTS/ STENTS | SENSITIVITY (%) | SPECIFICITY (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Mieghem et al. | Circ | 2007 | 16/64 | 74 | 100 | 91 | 67 | 10 |

| NO. PATIENTS/STENTS | NOT EVALUABLE (%) | SENSITIVITY (%) | SPECIFICITY (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 482/682 | 12 (82/682) 95% CI: 9.7–15 | 91 (105/115) 95 CI: 85–96 | 93 (461/494) 95 CI: 91–95 | 76 (105/138) | 98 (461/471) |

The detail of the stent is variably, but usually fairly, defined by CCT. The metallic composition of the stent has a major effect on the brightness of the stent—for example, that of the ACS RX Multilink (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, IL) is 269 ± 19 HU, whereas that of the Sirius Carbostent (Sorin Biomedica Cardio, Saluggia, Italy) is 437 ± 29 HU. The metallic composition also affects the ability to image the detail of the stent. A sharp or detail reconstruction kernel often is used to minimize the blooming artifact caused by the metallic struts of a stent. This modulation of the technique is felt to increase the conspicuity of subtle neo-intimal hyperplasia within the stent. Use of a wide window (width 1500 HU; center 300 HU) is also recommended, as this, in conjunction with a sharper kernel, will minimize blooming artifact.

Restenosis or thrombosis is apparent as lower-attenuation material within the stent; visually or quantitatively, this can be referred to elsewhere in the vessel or better yet, to the ascending aorta: a reading of 0.81 predicts patency with a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 95%.

Expected severe artifact problems associated with imaging stents include:

- □

Small vessels or small stents

- □

Multiple stents at one site (overlap)

- □

Stents with more metal

- □

Calcium in underlying plaque

- □

Artifacts from sternal wires, clips, pacemakers

- □

Hypodense restenosis material in proximity to high-attenuation stent material

Some unusual stent-related problems, such as stent-induced coronary aneurysm formation, have been imaged by CCT.

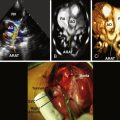

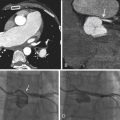

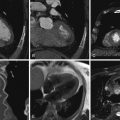

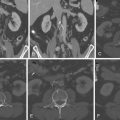

Adequate CCT Imaging of Patent Stents

Figures 7-1 through 7-7 show adequate CCT imaging of patent stents.