, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

A cavity is a gas-filled space, shown as a lucency or low-attenuation area, with identifiable wall (usually >4 mm in thickness) (Fig. 12.1). It can be seen within pulmonary consolidation, a mass, or a nodule. A cavity is usually produced by the expulsion or drainage of a necrotic portion of the lesion via the airways. It may contain a fluid level [1, 2].

Cavity

Definition

A cavity is a gas-filled space, shown as a lucency or low-attenuation area, with identifiable wall (usually >4 mm in thickness) (Fig. 12.1). It can be seen within pulmonary consolidation, a mass, or a nodule. A cavity is usually produced by the expulsion or drainage of a necrotic portion of the lesion via the airways. It may contain a fluid level [1, 2].

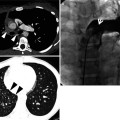

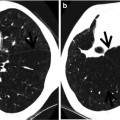

Fig. 12.1

Squamous cell carcinoma in a 69-year-old smoker man. Lung window image of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scan obtained at level of suprahepatic inferior vena cava shows a cavitary lesion (arrows) having irregular and variable wall thickness in right lower lobe

Diseases Causing the Cavity

Cavities are present in a wide variety of infectious and noninfectious processes. Malignancies are the most frequent noninfectious process causing lung cavitary lesion(s) and include primary lung cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) (Fig. 12.1), lymphoma, and Kaposi sarcoma particularly in HIV-infected patients, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and metastasis from an extrathoracic malignancy. Other noninfectious causes are antineutrophil cystoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated granulomatous vasculitis (former Wegener’s granulomatosis), pulmonary embolism and infarction and necrosis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma) (Fig. 12.2). Infectious conditions comprise bacterial infection (necrotizing pneumonia and lung abscess, septic pulmonary embolism (Fig. 12.3), and nocardiosis), mycobacterial infection (Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Fig. 12.4) and nontuberculous mycobacterial [NTM] pulmonary disease (Fig. 12.5)), fungal infection (aspergillosis (Figs. 12.6 and 12.7), zygomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococcosis), and parasitic infection (paragonimiasis) [1] (Table 12.1) (Fig. 12.8).

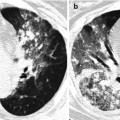

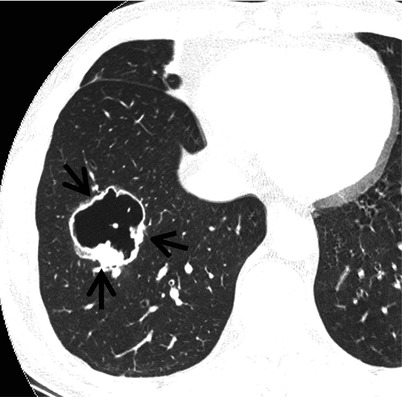

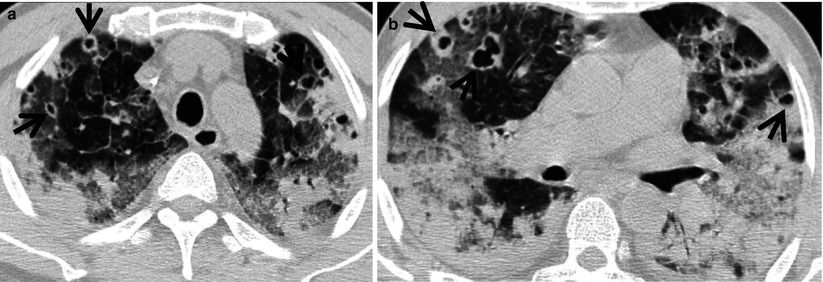

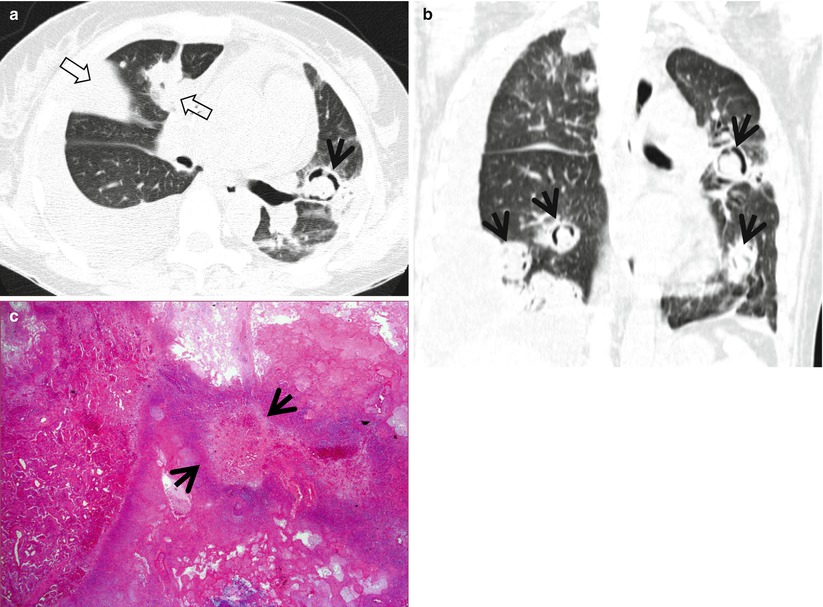

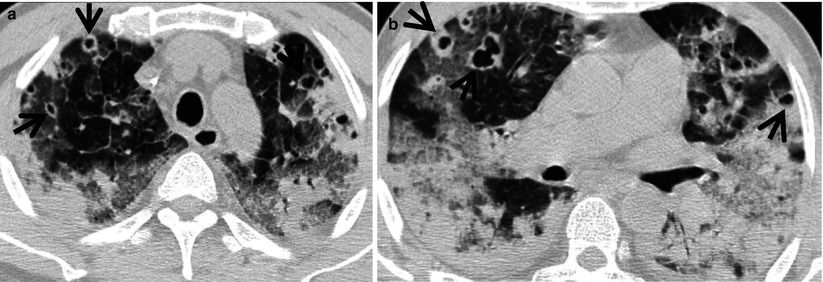

Fig. 12.2

Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a 47-year-old smoker woman (20-pack-year smoking history). (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and inferior pulmonary veins (b), respectively, show cavitating and noncavitating nodules in both lungs. Also note variable wall thickness of cavitating nodular lesions. (c) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) demonstrates nodular lesions with upper and middle lung zone predominance. (d) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen obtained from left upper lobe discloses a cystic lesion (arrows) having relatively thick wall which is composed of numerous Langerhans cells and other inflammatory cells. Also note mild inflammatory cell infiltration in pericystic interstitium (alveolar walls)

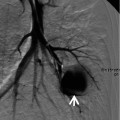

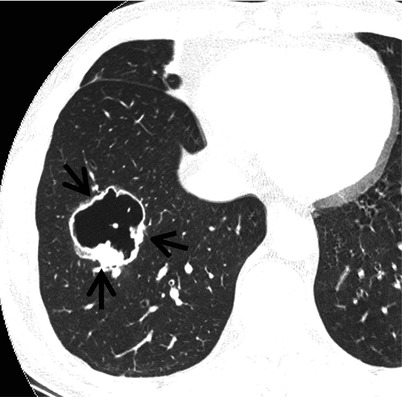

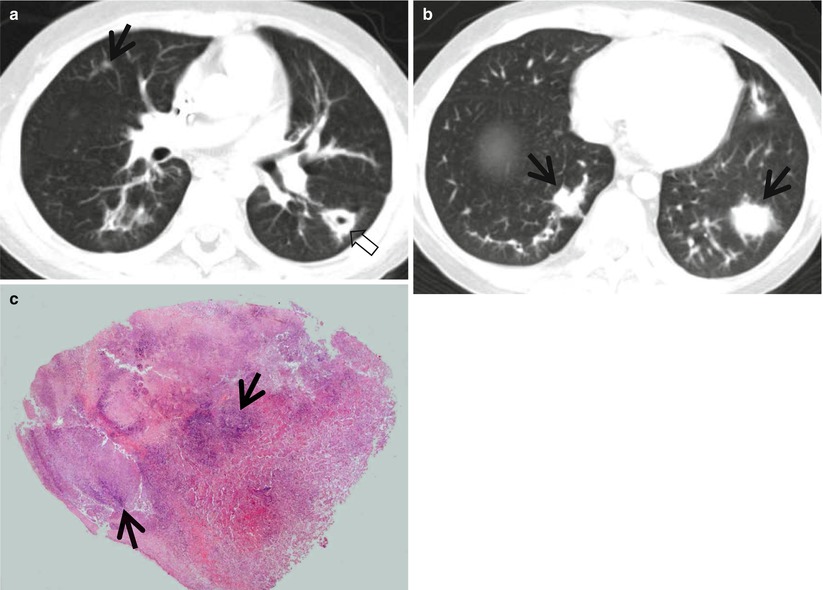

Fig. 12.3

Septic lung in a 58-year-old man with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus who has a history of electric burn on his left thigh. (a, b) Lung window images of CT (2.5-mm section thickness) scans obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and right bronchus intermedius (b), respectively, show bilateral extensive areas of ground-glass opacity and consolidation. Also note variable-sized cavitary lesions (arrows) in both lungs. Pleural effusions are also seen, bilaterally

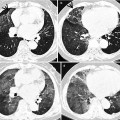

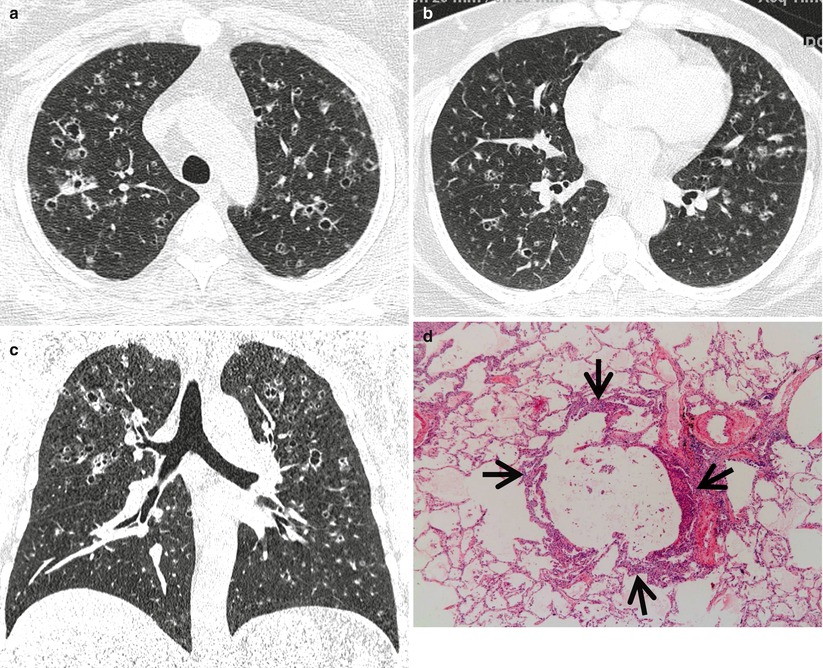

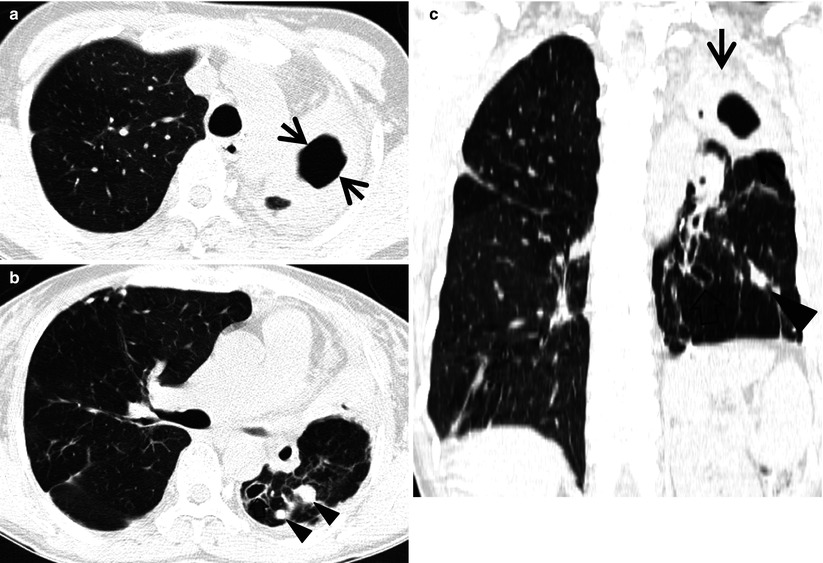

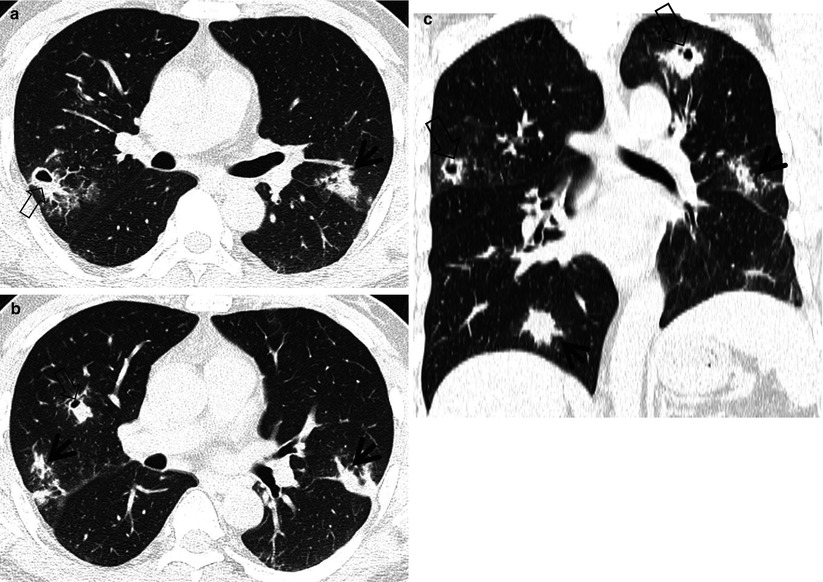

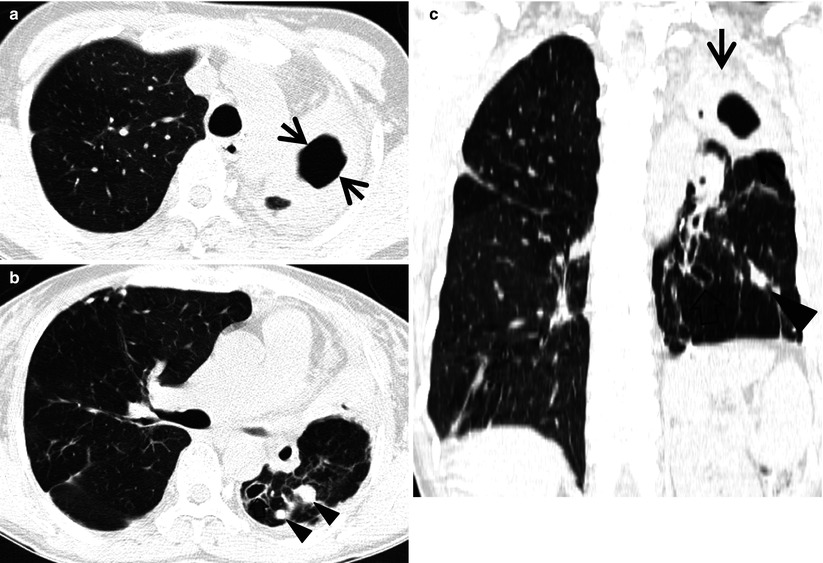

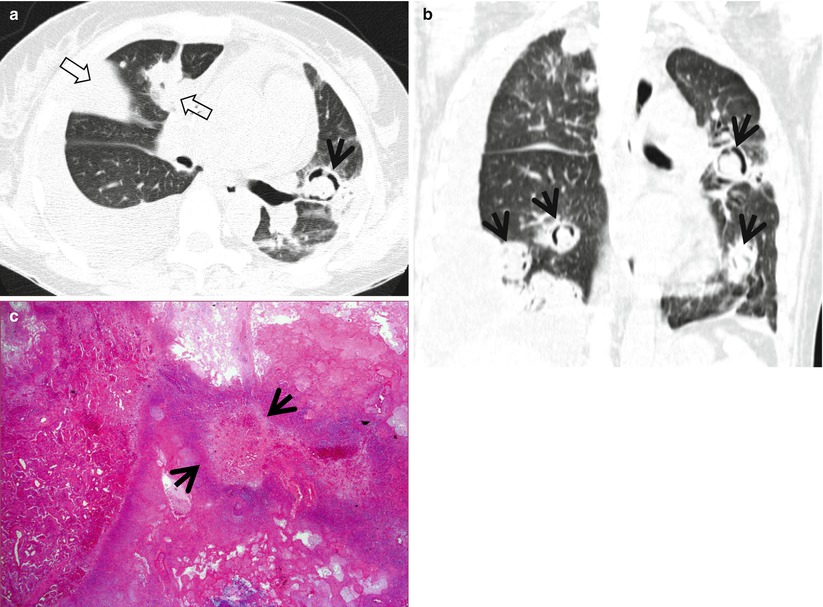

Fig. 12.4

Multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis in a 49-year-old woman. (a, b) Lung window images of CT (2.5-mm section thickness) scans obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and right upper lobar bronchus (b), respectively, show a large thick-walled cavitary lesion (arrows in a) in volume decreased left upper lobe and another smaller cavity (open arrow) and nodular lesions (arrowheads) in left lower lobe. Also note left pleural effusion and subcentimeter nodules in right upper lobe. (c) Coronal reformatted (2.0-mm section thickness) CT image demonstrates left upper lobe cavity (arrows) and thin-walled cavity (open arrow) and nodular lesion (arrowhead) in left lower lobe. Please note left pleural effusion. (d) Gross pathologic specimen obtained with left pneumonectomy displays a large cavity (arrows) in the left upper lobe, thin-walled cavity (open arrow) in the left lower lobe, multiple nodules containing caseation necrosis (arrowheads), and marked bronchial thickening due to inflammatory and fibrotic changes. (e) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of pathologic specimen discloses a necrotizing granuloma having palisading epithelioid histiocytes and eosinophilic materials (arrows) on its periphery and central caseating necrotic materials (C). Inset: small necrotizing granuloma

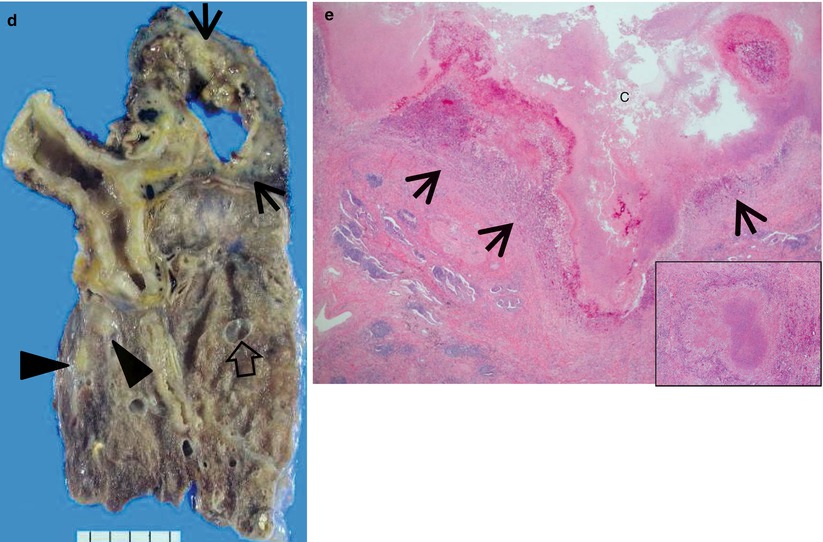

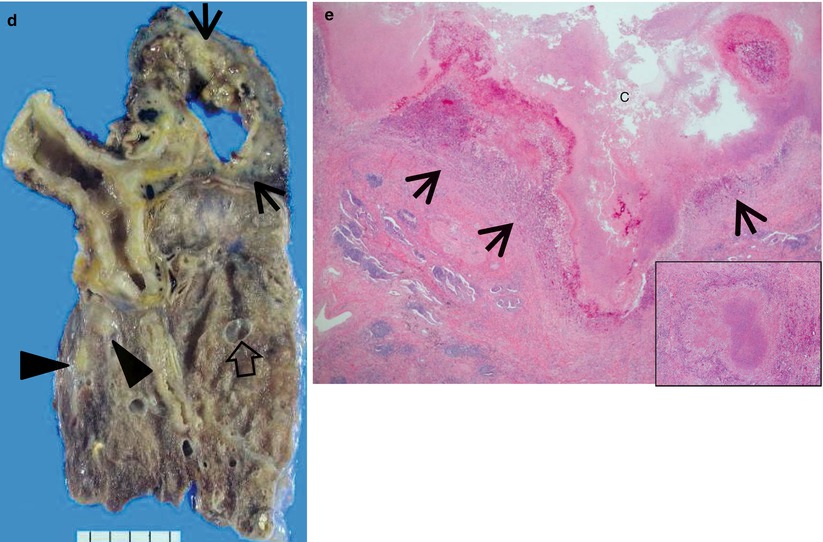

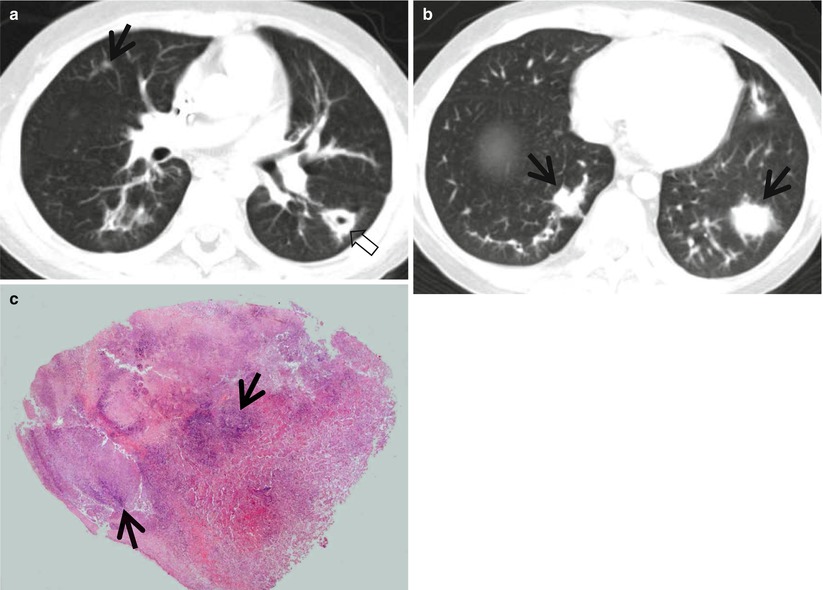

Fig. 12.5

Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease of upper lobe fibrocavitary form (M. intracellulare) in a 64-year-old man. (a) Lung window image of CT scan (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at level of great vessels shows relatively even cavity wall thickness (arrows) in left apical area. Also note variable-sized nodules. (b) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) demonstrates two cavitary lesions (arrows) in left upper lobe. Also note wall thickening (open arrow) of bronchus draining larger cavity. (c) Gross pathologic specimen obtained with left upper lobectomy discloses several thin-walled cavities (arrows), variable-sized granulomas (arrowheads), and bronchiectasis (open arrows)

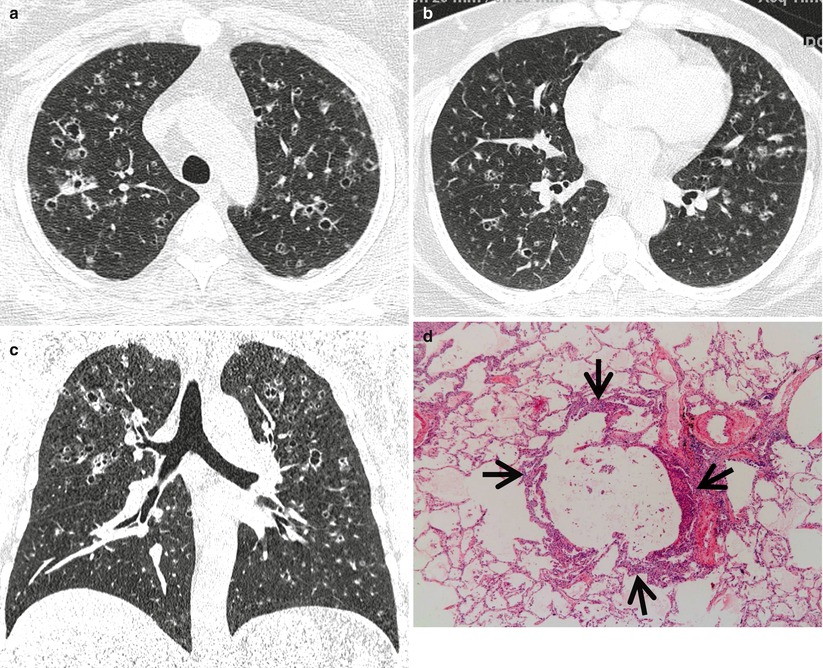

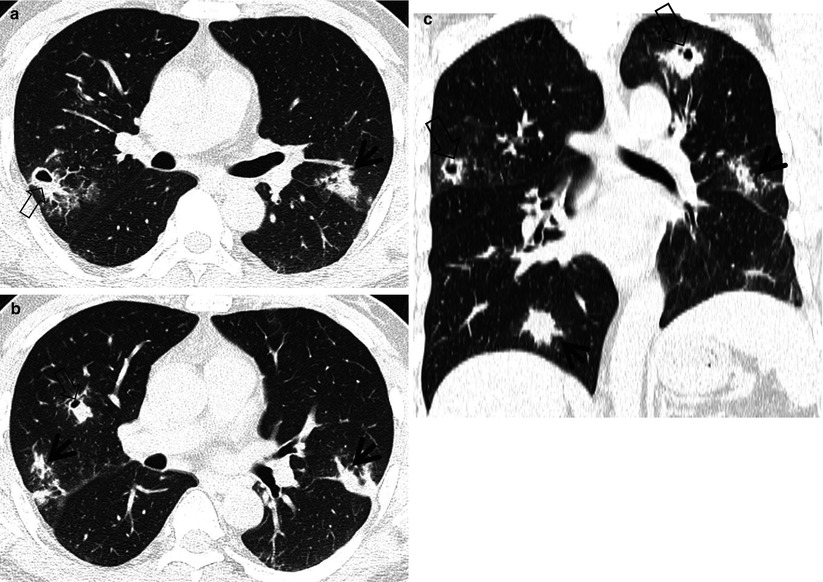

Fig. 12.6

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a 27-year-old woman with acute myeloid leukemia. (a) Lung window image of CT scan (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at level of right bronchus intermedius shows a cavitating nodule (crescent sign) (arrow) in lingular division of left upper lobe and cavitating and noncavitating areas (open arrows) of consolidation in right upper lobe. Also note bilateral pleural effusions. (b) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) demonstrates multiple cavitating nodules (arrows) showing crescent sign. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen disclosed fungal organisms (arrows) within cavitated infarction area

Fig. 12.7

Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in an 11-year-old boy with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. (a, b) Lung window images of CT (5.0-mm section thickness) scans obtained at levels of right bronchus intermedius (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show multiple nodules (arrows) showing halo sign. Also note a cavitating nodule (open arrow) in superior segment of left lower lobe. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen discloses necrotizing fungal pneumonia with abscess formation. Please note blue fungal hyphae (arrows) in necrotic spaces

Table 12.1

Common diseases manifesting as cavity

Disease | Key points for differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

Primary lung cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) | Thick-walled cavity with a nodular inner surface |

ANCA-associated granulomatous vasculitis | Multiple, bilateral, subpleural nodules, or masses |

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis | Pulmonary nodules and masses with central low attenuation and peripheral rim enhancement, and ground-glass opacity halo |

Pulmonary infarction | Peripheral wedge-shaped consolidation with central lucencies |

Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Cavitating and noncavitating nodules in upper and middle lung zones |

Lung abscess | |

Septic pulmonary embolism | Multiple, peripheral nodules with a feeding vessel sign |

Mycobacterial infection | Single or multiple large cavitary lesion in the upper lobes, satellite centrilobular nodules |

Fungal infection | Cavity with an air-crescent sign |

Parasitic infection (PW) | Cavitary nodules or masses in the subpleural or subfissural areas |

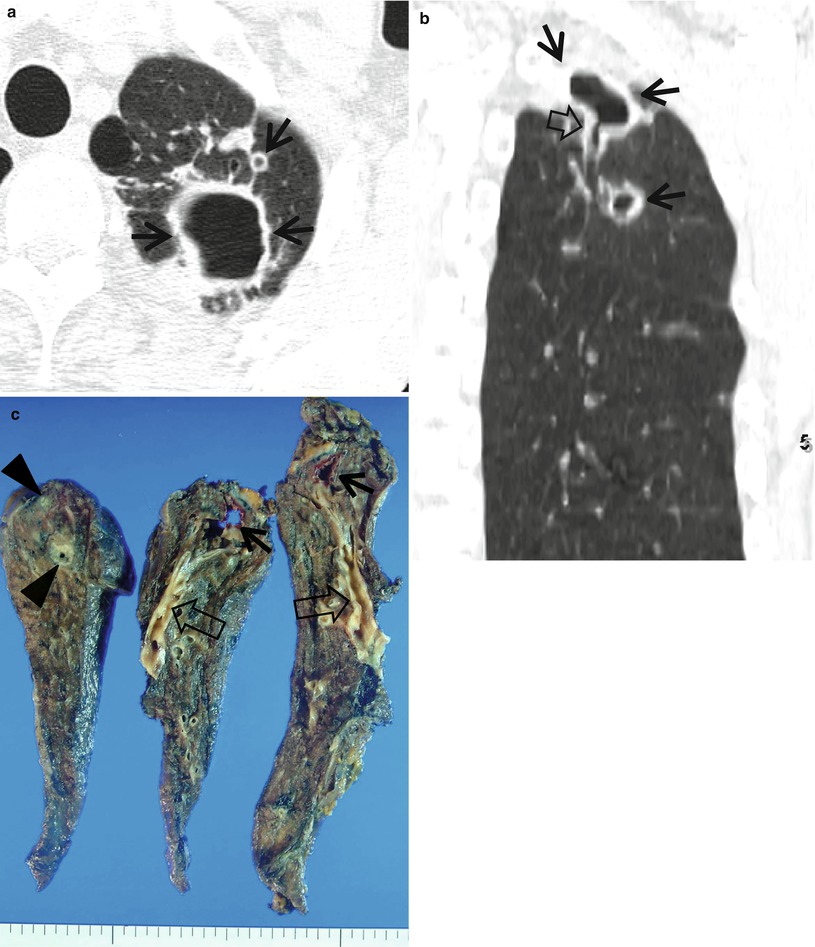

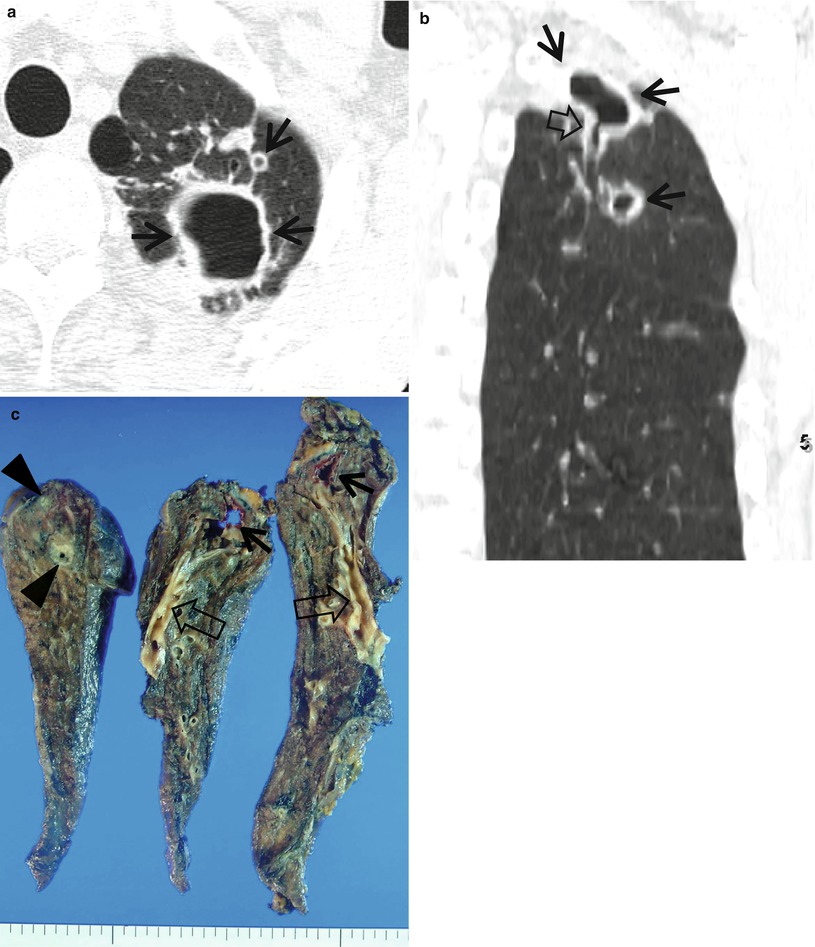

Fig. 12.8

Pulmonary Paragonimus westermani (PW) infestation in a 46-year-old man proved by sputum smear showing parasitic eggs and positive ELISA test for PW. (a, b) Lung window images of consecutive CT (2.5-mm section thickness) scans obtained at levels of right bronchus intermedius show multiple nodules with (open arrows) or without (arrows) internal cavity. (c) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) demonstrates multiple cavitating (open arrows) and noncavitating (arrows) nodules in both lungs

Distribution

In Langerhans cell histiocytosis, the cavitating nodules are associated with noncavitating nodules and are distributed mainly in the upper and middle lung zones, sparing the lower lung zones. The presence of a single or multiple large cavitary lesions in the upper lobes suggests the diagnosis of mycobacterial disease [3]. In NTM disease, cavitation is common in the upper lobes and frequently associated with apical pleural thickening and pulmonary emphysema (upper lobe fibrocavitary form) [4]. In pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis, necrotic or cavitary nodules or masses are usually located in the subpleural or subfissural areas [5].

Clinical Considerations

Cigarette smoking is highly related to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and the cavitating nodules in the disease are reversible with corticosteroid or cytotoxic drug therapy [6]. In tuberculous infection, imaging findings have implications as for host immune status (e.g., lymph node enlargement and lower lung zone parenchymal opacity in HIV-infected patients) of patients, but whether a patient’s disease is due to recently transmitted (epidemiologically primary infection) or remotely acquired infection (reactivation tuberculosis) cannot be determined from the radiographic findings [7]. The most common risk factor for pulmonary nocardiosis is underlying lung disease such as asthma, bronchiectasis, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. People with systemic immunodeficiency associated with cancer chemotherapy, HIV infection, organ transplantation, or long-term corticosteroid use are also at increased risk for pulmonary Nocardia infection [1]. Cryptococcal infections are mostly common in immunocompromised patients such as those with AIDS, who underwent organ transplantation, or who have a hematologic malignancy. These infections are relatively rare in immunocompetent patients [8]. Paragonimiasis infection occurs when humans eat infected crabs or crayfish containing metacercaria of Paragonimus.

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

1.

In cavitary squamous cell carcinoma, the borders of tumor are often irregular or lobulated. The cavities are usually thick walled and have a nodular inner surface. Discordance between the inner and outer walls of a cavitary lesion (e.g., smooth inner walls and uneven outer walls or uneven outer and inner walls and discordant uneven sectors) is more common in peripheral lung cancer cavity, and concordance between the walls (e.g., smooth inner and outer walls or uneven outer and inner walls and concordant uneven sectors) is more common in single pulmonary tuberculous cavity. Thus, analyzing the characteristics of cavitary internal and external walls on CT is valuable in differentiating between peripheral lung cancer cavity and single pulmonary tuberculous thick-walled cavity [9].

2.

In pulmonary tuberculosis, satellite centrilobular nodules or tree-in-bud patterns suggesting bronchogenic spread usually seen around the cavities. The presence of multiple cavities and young patient age (20s or 30s) suggest multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis [10].

3.

The presence of a cavity on CT of the lung may help exclude the diagnosis of viral infection in immunocompromised patients and lung infection [11].

4.

The air-crescent sign in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, defined as crescents of air surrounding nodular lesions, is observed in up to 63 % of patients. The sign, occurring in about half of the patients with recovery from neutropenia, is caused by tissue ischemia and subsequent necrosis due to fungal angioinvasion [12]. Whether a mural nodule within a cavitary lesion is contrast-enhanced or not is one of the most important features in making a differential diagnosis between an intracavitary aspergilloma and a cavitary lung cancer [13].

5.

The presence of a “feeding vessel” sign, in which a distinct vessel is seen leading to the center of a pulmonary nodule, may suggest the diagnosis of septic embolism, but the sign is nonspecific (may be seen in pulmonary metastatic nodules) [14].

6.

According to one CT report [8], cavitation within lung lesions in pulmonary cryptococcosis was noted in only four (17 %) of 23 patients. The lung lesions of cryptococcosis in non-AIDS patients show an indolent course, slowly progressive even without adequate treatment and does not show a rapid resolution even with antifungal treatment [8].

7.

Subpleural or subfissural necrotic nodule with adjacent pleural thickening and subpleural linear opacities (worm migration track) leading to a necrotic nodule can be an important clue in the diagnosis of pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis on CT [5].

Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma as a Cavitary Lesion

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant epithelial tumor showing keratinization or intercellular bridges that arise from bronchial epithelium. Two-thirds of SCCs are centrally located, arising from proximal bronchi, and one-third of cases are peripherally located (Fig. 12.1). Tumors are firm gray-white masses with areas of necrosis and cavitation, and central lesions often have endobronchial growth, which may occlude the lumen of airways and cause obstructive changes. Tumor cells are polygonal and hyperchromatic and have irregular nuclei and prominent nucleoli; the amount of cytoplasm is variable from abundant to scanty. There are several histologic variants as follows: papillary variant, clear-cell variant, small-cell variant, basaloid variant, and alveolar space-filling type of peripheral SCC [15].

Symptoms and Signs

Hemoptysis is an important feature of SCC of the lung that can be related both to central airway location of the tumor and to an increased propensity to cavitation [16]. Shortness of breath and fever occur due to atelectasis and postobstructive pneumonia. In general, it tends to be locally aggressive with less frequent metastasis to distant organ than adenocarcinoma of the lung. Chest wall invasion causes chest pain. Hypercalcemia may be present as a paraneoplastic syndrome secondary to secretion of parathyroid hormone-related protein.

CT Findings

The most common radiologic abnormality of SCC is a large central mass and atelectasis secondary to the airway obstruction [17]. One-third of SCCs present as intraparenchymal nodules or masses that lack apparent connection to a bronchus (Fig. 12.1). There has been a more recent shift, however, to a greater percentage of tumors occurring in the periphery of the lung with 53 % in one study [18]. The borders of the nodule are often irregular or lobulated. Approximately 10 % of SCCs show cavitation. The cavities are usually thick walled and have a nodular inner surface. Discordance between the inner and outer walls of a cavitary lesion (e.g., smooth inner walls and uneven outer walls or uneven outer and inner walls and discordant uneven sectors) is more common in peripheral lung cancer cavity and concordance between the walls (e.g., smooth inner and outer walls or uneven outer and inner walls and concordant uneven sectors) is more common in single pulmonary tuberculous cavity. Thus, the characterization of a cavitary lesion according to its cavitary internal and external walls on CT is valuable in differentiating between peripheral lung cancer cavity and single pulmonary tuberculous thick-walled cavity [9].

CT-Pathology Comparisons

In SCC, necrosis of the central portion of the tumor is common, especially in larger ones. Possibly because of their intimate association with proximal airways, the necrotic material can drain relatively easily and cavity formation is common. Occasionally, a cavity results from infection and abscess formation in an area of obstructive pneumonitis. Nodular inner surface of cavity is probably related to local differences in necrosis and growth rate within the tumor.

Patient Prognosis

Surgical resection is a potentially curative treatment of the early stage of SCC of the lung, with a 5-year survival rate up to 70 %. Combined modality therapy with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy can improve the survival in the patients with stages II and III. Clinical trials with novel targeted agents for advanced stage lung cancer are ongoing. Prognosis is poor (5-year survival 1 %) in the stage IV group.

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare interstitial lung disease caused by proliferation of Langerhans cells. It can either be limited to the lung (pulmonary LCH) or be part of a systemic LCH. Langerhans cells are characterized by large, folded nuclei, vesicular chromatin, and abundantly pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm. LCH can be divided into two phases: early cellular (proliferative) and late fibrotic phases. Early cellular phase is characterized by nodular proliferation of Langerhans cells centered on small airways, such as terminal bronchioles, and cystic dilatation of involved airways and eosinophils is commonly seen (Fig. 12.2). In late fibrotic phase, Langerhans cells are diminished and replaced by fibrous tissue [6].

Symptoms and Signs

Clinical presentation of pulmonary LCH is variable [19]. Despite diffuse lung involvement, symptoms can be minor or absent. Initially patients often attribute their symptoms to smoking. Dry cough and dyspnea on exertion are present in approximately two-thirds of the patients. Spontaneous pneumothorax responsible for chest pain occurs in up to 20 %. Bone lesions (<20 %), diabetes insipidus with polyuria and polydipsia (5 %), and skin lesions are the most common extrapulmonary manifestations.

CT Findings

The incidence of these findings depends on the stage of disease. The most common thin-section CT findings of early LCH are multiple poorly defined small nodules with a centrilobular distribution [20, 21] (Fig. 12.2). Nodules measure 1–5 mm in diameter, although larger nodules are seen in approximately 30 % of cases. Their margins may be smooth or irregular. Larger nodules may show lucent centers. As the disease progresses, the nodules tend to cavitate, and a combination of cysts and nodules is characteristic (Fig. 12.2). Cysts are often seen in association with nodules but may be the only HRCT finding. They range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter and may be round or irregular in shape. Regardless of the stage, the abnormalities are most severe in the upper and mid-lung zones; the lung bases are relatively spared (Fig. 12.2). Less common findings include reticular pattern, interlobular septal thickening, large bullae, and ground-glass opacity. The radiologic abnormalities may regress, resolve completely, become stable, or progress to advanced cystic changes. According to a study, more than half of patients show improvement on follow-up CT scans because even thin-walled cysts harbor active inflammatory cells in their walls and show improvement with treatment [6]. Spontaneous pneumothorax is seen in approximately 10 % of patients.

CT-Pathology Comparisons

LCH is histopathologically characterized by peribronchiolar proliferation and infiltration of Langerhans cells that form stellate nodules. With progression, cellular nodules are transformed into cavitary nodules or thin-walled cysts (Fig. 12.2). In advanced stages, fibrotic scars are surrounded by enlarged and distorted air spaces. Centrilobular nodules seen on HRCT correspond histopathologically to the area of peribronchiolar granulomas composed of Langerhans cell, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages [6]. Lucent centers seen in large nodules correspond to a dilated bronchiole surrounded by thickened peribronchiolar interstitium. Thick- and thin-walled cystic lesions seen on CT consist of a central cavity surrounded by a thick and thin wall composed of Langerhans cell sheets and eosinophils. In thin-walled cysts, inflammatory cell infiltrations along the alveolar walls as well as pericystic emphysema are seen. Bizarre cysts seen on CT have irregular and wavy wall on pathology, and the walls of cystic lesions are composed of numerous Langerhans and other inflammatory cells or fibrotic changes. Several cysts coalesce with surrounding cysts via the destruction of their walls.

Patient Prognosis

The natural history of the disease is widely variable and unpredictable [19]. Approximately 50 % of patients experience a favorable outcome, with after the cessation of smoking or with glucocorticoid therapy. Approximately 10–20 % of patients have early severe manifestations, consisting of recurrent pneumothorax or progressive respiratory failure. Finally, 30–40 % of patients show persistent symptoms of variable severity that remain stable over time.

Septic Pulmonary Embolism

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Septic pulmonary embolism causes lung abscess and septic infarction. Localized suppurative necrosis of lung tissue and cavitation containing necrotic fluid or debris are observed.

Symptoms and Signs

Septic pulmonary embolism is an uncommon disorder presenting with fever; respiratory symptoms such as cough, sputum, hemoptysis, chest pain, and dyspnea; and lung infiltrates in the presence of an extrapulmonary source of infection [22]. Since infected thrombus can cause lung abscess, septic infarction, empyema, bronchopleural fistula, shock, and death; respiratory symptoms are variable and often nonspecific. Historically, septic pulmonary embolism has been associated with intravenous drug use, pelvic thrombophlebitis, and suppurative processes in the head and neck. However, increasing use of indwelling catheters and devices as well as increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients has changed the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of septic pulmonary embolism.

CT Findings

Septic pulmonary embolism is characterized by the presence of multiple nodules that usually measure 1–3 cm in diameter and that frequently cavitate [23] (Fig. 12.3). The nodules often have ill-defined margins and have a feeding vessel sign [14]. The subpleural wedge-shaped areas of consolidation often with central areas of necrosis or cavitation are also seen. According to a study, cavitation within the nodules is more common in pulmonary septic embolism caused by gram-positive microorganisms, whereas ill-defined margins are more common in pulmonary septic embolism caused by gram-negative microorganisms [24].

CT-Pathology Comparisons

Nodules seen on CT correspond to areas of infarction and hemorrhage caused by ischemia and neutrophilic exudates and necrosis of lung parenchyma caused by toxins from organisms. The subpleural wedge-shaped areas of consolidation correspond to areas of hemorrhage or infarction caused by occlusion of pulmonary arteries by septic emboli.

Patient Prognosis

Early diagnosis is the most important to improve the prognosis. With appropriate antimicrobial therapy and control of the infectious source, resolution of the illness and avoidance of potential complications can be expected.

Cavitary Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is usually seen as a necrotizing consolidative process predominantly in lung apices. Pulmonary TB may be seen as a Ghon lesion (1–2 cm, round, white-gray pulmonary nodule with central necrosis), a Ghon complex (Ghon lesion plus hilar lymphadenopathy), or a Ranke complex (fibrosis and calcification of the Ghon complex via cell-mediated immunity). Histologically, both necrotizing (caseating) and nonnecrotizing granulomas can be seen in lung parenchyma or lymph nodes. Organisms (4-μm beaded rods) can be demonstrated using acid-fast stains (Ziehl–Neelsen), although a negative acid-fast stain does not rule out tuberculosis. Langerhans-type multinucleated giant cells are frequently seen [25] (Fig. 12.4).

Symptoms and Signs

Cough is the most common symptom of pulmonary TB. Cavitary pulmonary TB is often accompanied by hemoptysis. Constitutional symptoms, including fever, malaise, fatigue, weight loss, night seating, and anorexia, are often present [26].

CT Findings

The CT findings of active cavitary pulmonary TB include cavities, centrilobular small nodules, and branching linear structures, giving a tree-in-bud appearance, lobular consolidation, and bronchial wall thickening [25, 27]. Cavitation in single or multiple sites is evident in 40–45 % of active pulmonary TB [28] (Fig. 12.4). Walls of cavities may range from thin and smooth to thick and nodular; air–fluid levels have been reported to occur in 9–21 % of tuberculous cavities. Bronchogenic spread of disease occurs when an area of caseous necrosis liquefies and communicates with the bronchial tree. Bronchogenic spread manifests as centrilobular small nodules and tree-in-bud patterns around or distant site from the cavities.

CT-Pathology Comparisons

The CT findings of active cavitary pulmonary TB include cavities, centrilobular small nodules and branching linear structures, lobular consolidation, and bronchial wall thickening [25, 27]. Cavitation is centrilobular in location, and several centrilobular cavities progressively coalesce into a larger cavity (Fig. 12.4). The wall of the cavity consists of caseous materials, epithelioid cells with multinucleated giant cells, granulation tissue, and a fibrous capsule. Histopathologic analysis indicates that centrilobular small nodules occur as a result of impaction of caseous material within or around the terminal or respiratory bronchioles and sometimes within the alveolar ducts. The airways show a yellowish thickening of the wall with caseation necrosis. Centrilobular nodules grow and coalesce into lobular consolidation, consisting of centrally located granulomas that contain caseation necrosis and marginal nonspecific inflammation.

Patient Prognosis

Cure rate for drug-sensitive TB is more than 95 % with the current standard four-drug treatment regimen of first-line drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) for 6 months [26]. Prolonged medication for at least 20 months with second-line drugs is necessary for multidrug-resistant TB. Extensively drug-resistant TB is extremely difficult to treat. When the disease of drug-resistant cavitary TB is localized, surgical resection of the lung lesion can be done with medical therapy.

Paragonimiasis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Paragonimiasis is infection by trematodes of the genus Paragonimus, with most infections of humans with flukes of this genus attributed to P. westermani. It is an important human disease in Far East Asia and parts of Latin America and Africa. The use of raw or incompletely cooked crabs or crayfish and their juices for food or medicine is the most important method of transmission. The worm evokes a cystic necrotizing granulomatous and fibrotic response with tissue eosinophilia. The ova of Paragonimus are approximately 80 μm in size and show a flattened operculum [5].

Symptoms and Signs

Initially, pulmonary paragonimiasis manifests as chronic cough and hemoptysis. Chest pain and dyspnea can occur when pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax develops. Subcutaneous nodules can be found in the advanced case.

CT Findings

Typical CT findings of pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis are a poorly marginated subpleural or subfissural nodule that frequently contains a low-opacity necrotic area or cavity (Fig. 12.8), focal pleural thickening, and subpleural linear attenuation lesions leading to a necrotic peripheral nodule, thin-walled cyst, pneumothorax, or hydropneumothorax [5, 29]. These imaging findings correlate well with the stage of the disease [29]. Early findings are caused by the migration of juvenile worms and include pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax, airspace consolidation, and linear opacities. Later findings resulting from worm cysts include subpleural nodules or masses, thin-walled cysts, and bronchiectasis.

CT-Pathology Comparisons

In a study of the correlation between CT and histologic findings in pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis, the subpleural nodule is a necrotic granuloma containing multiple eggs and organizing pneumonia with granulation tissue. Adjacent pleural thickening is composed of fibrotic thickening with some areas of lymphocytic infiltration [5].