, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Cavities

Definition

Please refer to section “Cavity” in Chap. 12.

Diseases Causing Cavities

In patients with diffuse lung diseases, multiple cavities are seen in patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fungal infection, and sarcoidosis. Cavitary nodules are also seen in patients with rheumatoid lung disease (Fig. 23.1), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated granulomatous vasculitis (former Wegener’s granulomatosis), septic embolism, and metastatic tumors (squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck and the uterine cervix) (Fig. 23.2).

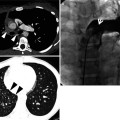

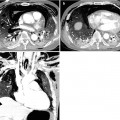

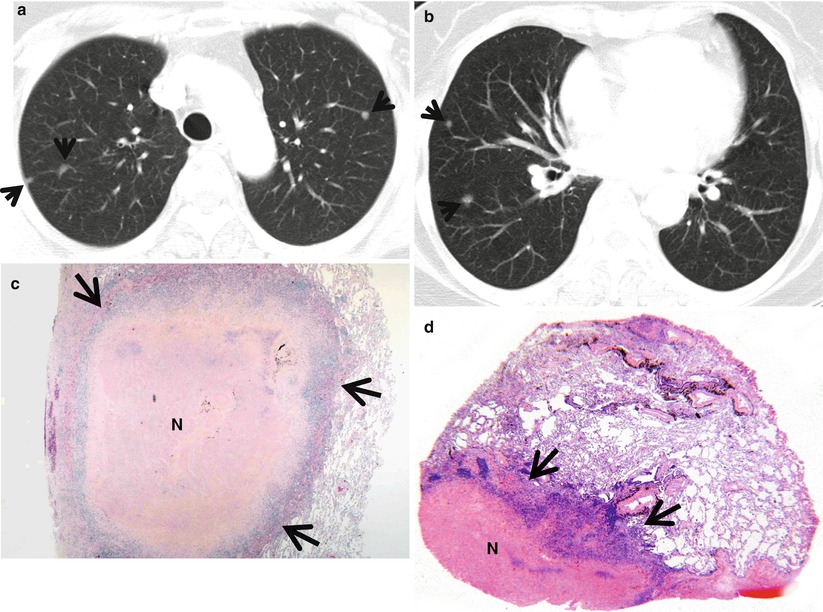

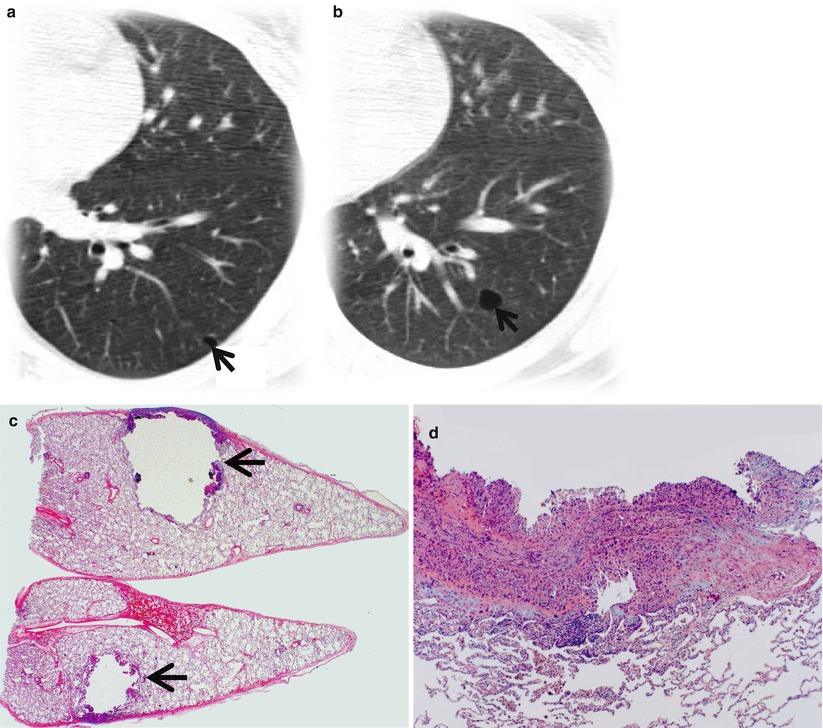

Fig. 23.1

Rheumatoid nodules in a 70-year-old woman who has suffered from rheumatoid arthritis for 10 years. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and basal trunks (b), respectively, show multiple small nodules (arrows) in both lungs. Mediastinal window images exhibit necrosis in central portion of nodules. (c) Low-magnification (×4) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe demonstrates a nodule containing necrotic portion (N) and surrounding rim (arrows) of epithelioid histiocytes and fibrotic tissue. (d) Another low-magnification (×10) photomicrograph discloses necrotic portion (N), a rim of epithelioid histiocytes and fibrotic tissue (arrows), and normal lung

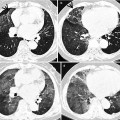

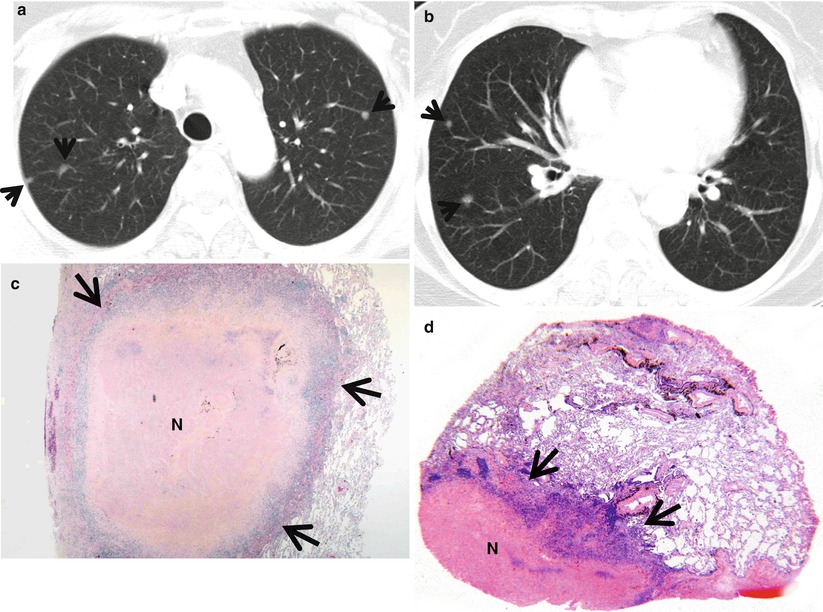

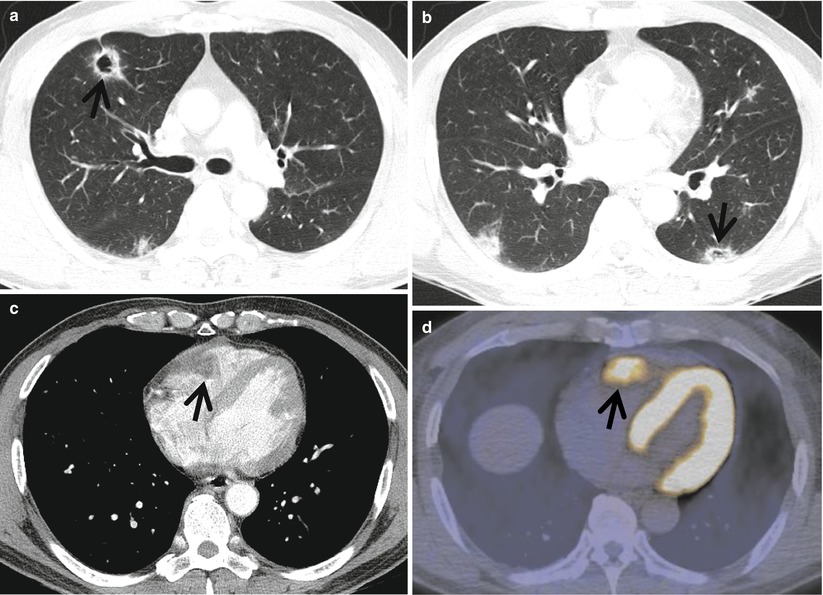

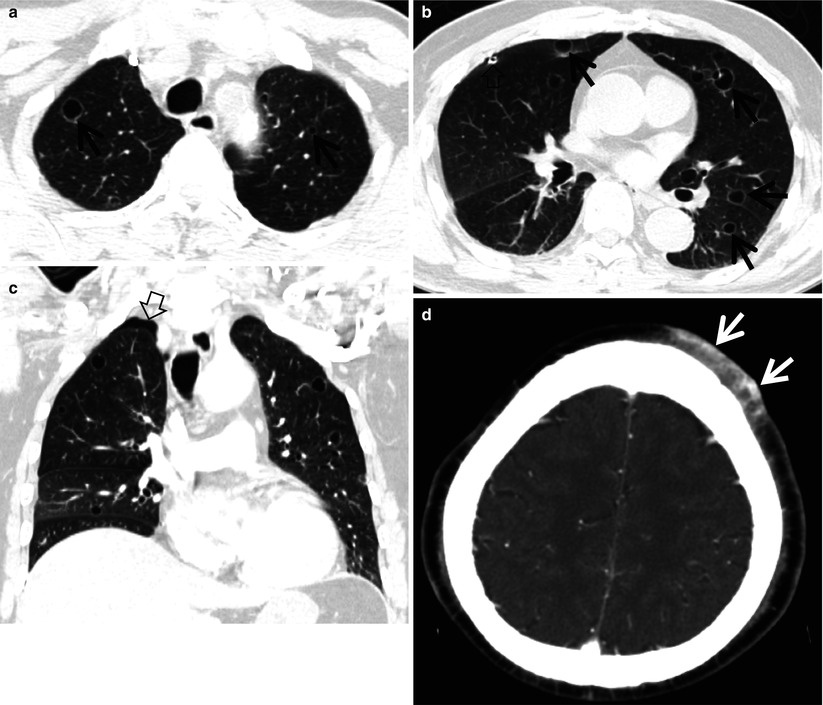

Fig. 23.2

Cavitary lung nodules representing pulmonary metastatic nodules in a 50-year-old man with renal cell carcinoma. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of right upper lobar bronchus (a) and basal trunks (b), respectively, show multiple cavitating (arrows) and noncavitating nodules in both lungs. (c) Enhanced CT scan obtained at level of cardiac ventricle shows a low-attenuation nodule (arrow) in right ventricle abutting lateral wall of the chamber. (d) Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography displays high uptake of glucose (arrow) at right ventricular nodule. Arrows in (c) and (d) indicate metastatic nodules in right cardiac ventricle

Distribution

In Langerhans cell histiocytosis, the cavitating nodules are associated with noncavitating nodules and are distributed mainly in the upper and middle lung zones, sparing the lower lung zones [1]. Cavitary nodules in patients with (ANCA)-associated granulomatous vasculitis have no predilection for any lung zones [2]. Rheumatoid lung nodules, metastatic tumors, fungal infection, and septic embolism nodules tend to predominate in the lung periphery [3–5].

Clinical Considerations

Cigarette smoking is highly related to pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and the cavitating nodules in the disease are reversible with corticosteroid or cytotoxic drug therapy [6]. Immunocompromised patients and patients with underlying lung disease are at increased risk of fungal infection. Rheumatoid lung nodules are typically seen in patients with subcutaneous nodules and tend to wax and wane in proportion to the activity of the arthritis [3]. Septic embolism occurs most commonly in intravenous drug users and in immunocompromised patients with central venous lines. The site of the primary neoplasm with cavitation is most frequently in the head and neck in men and the uterine cervix in women [7]. Cavitation also may occur in metastatic adenocarcinomas, particularly in lesions originating from the large bowel, and in metastatic sarcoma, particularly osteogenic.

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

Diseases | Distribution | Clinical presentations | Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zones | ||||||||||||

U | M | L | SP | C | R | BV | R | Acute | Subacute | Chronic | ||

LCH | + | + | + | + | + | Associated with irregular cysts or nodules, spare CPA | ||||||

Fungal infection | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | With GGO halo | ||||

Sarcoidosis | + | + | + | + | + | Mediastinal or hilar LN enlargement, female predominance, African Americans | ||||||

Rheumatoid nodules | + | + | + | + | + | + | Variable in size, unpredictable natural course | |||||

ANCA-associated granulomatous vasculitis | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Large necrotic area on enhanced scans | ||||

Septic lung | + | + | + | + | + | + | Feeding vessel sign | |||||

Pulmonary metastasis | + | + | + | + | + | + | Variable-sized nodules | |||||

Rheumatoid Lung Nodules

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The rheumatoid lung nodules have a necrotic center of finely granular eosinophilic debris surrounded by a capsule of chronic inflammatory granulation tissue. The boundary between dead and viable tissue is marked by a characteristic palisade of radially oriented macrophages (Fig. 23.1). The inflammatory cells include a small number of giant cells as well as plentiful lymphocytes and plasma cells [8].

Symptoms and Signs

Most patients with rheumatoid lung nodules are asymptomatic. Occasionally, cavitation may lead to hemoptysis [9]. Due to their typical subpleural distribution, complications, including pneumothorax, empyema, pleural effusions, and bronchopleural fistula, may occur.

CT Findings

Rheumatoid nodules have a maximum diameter of 0.5–5.0 cm and are usually located in peripheral zones of the upper and middle lung regions [10] (Fig. 23.1). Pulmonary nodules may increase in size or resolve spontaneously. Cavitation of nodules is common and is rarely associated with rupturing into the pleural space, producing bronchopleural fistula, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or empyema [11]. Calcification of rheumatoid pulmonary nodules is not a frequent finding but may be seen in some patients with Caplan syndrome.

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Rheumatoid pulmonary nodule is pathologically identical to subcutaneous rheumatoid nodule. They contain three histologically distinct zones: central fibrinoid necrosis, surrounding palisading epithelioid cells, and an outer zone of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts [12]. The necrotic central zone becomes cavitary or cystic, likely with the resolution of necrosis and subsequent inflation resulting from airflow in the lumen. Therefore, patients exhibit rheumatoid pulmonary nodules in various stages from new nodules with central necrosis to older nodules with cavitary or cystic changes.

Patient Prognosis

Rheumatoid lung nodules may remain stable, regress spontaneously, or enlarge. Depending on the clinical circumstances, serial radiographic follow-up or surgical resection may be required.

Cavitary Metastasis

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Cavitation in pulmonary metastases is thought to be uncommon. The primary sites were the large intestine, opposite lung, cervix, stomach, esophagus, pancreas, larynx, and mesenchymal tumors. It seems that the principal cause of necrosis and subsequent cavitation in metastatic tumors of the lung is interference with their blood supply by vascular involvement [13].

Symptoms and Signs

Significant number of patients with cavitary lung metastasis is asymptomatic. Hemoptysis can occur. Nonspecific symptoms including cough, vague chest discomfort, and dyspnea can result from a very large tumor burden. Constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, anorexia, and generalized weakness may be accompanied.

CT Findings

CT finding of cavitary metastasis consists of multiple nodules with or without cavitation (Fig. 23.2). The size of nodules range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and nodules are usually of varying size. They tend to be most numerous in the outer third of lungs, particularly the subpleural regions of the lower zones, and have a random distribution within the secondary pulmonary lobules [14, 15]. Most nodules are round and have smooth margins. They may be lobulated, however, and have irregular margins. The wall of cavitary metastatic nodule is generally thick and irregular, although thin-walled cavities can be found with metastases from sarcomas and adenocarcinomas [7].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Patient Prognosis

Prognosis of the patients with cavitary lung metastasis is poor since the primary tumor is not highly responsive to anticancer chemotherapy.

Cysts

Definition

A cyst is a round parenchymal lucency or low-attenuating area with a well-defined interface with normal lung. Cysts have variable wall thickness but are usually thin walled (<2 mm). The cysts usually contain air but occasionally contain fluid or solid material [16] (Fig. 23.3).

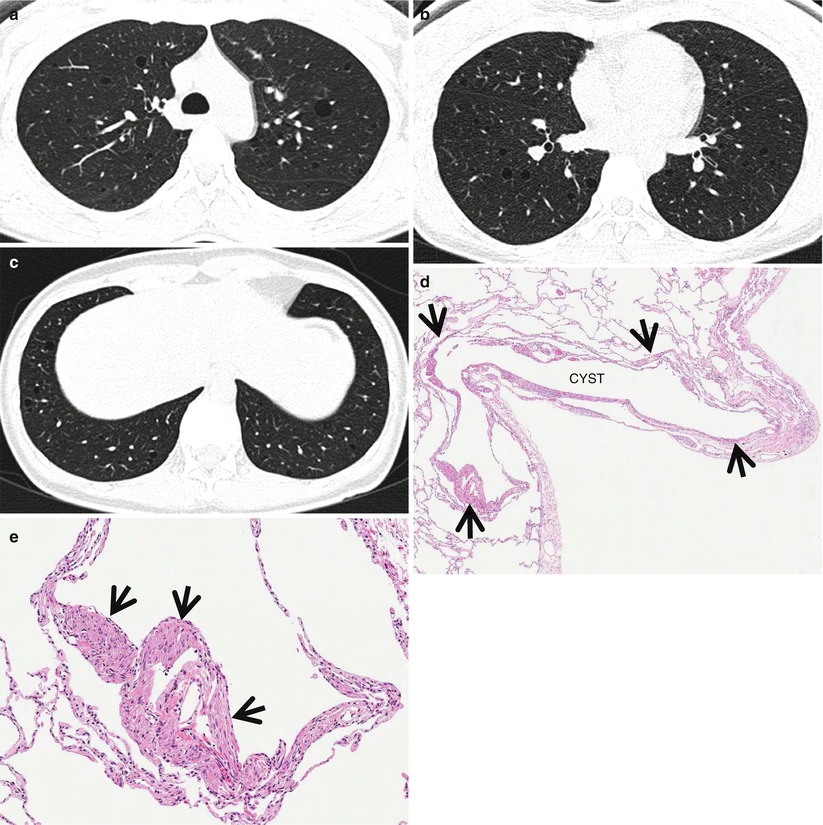

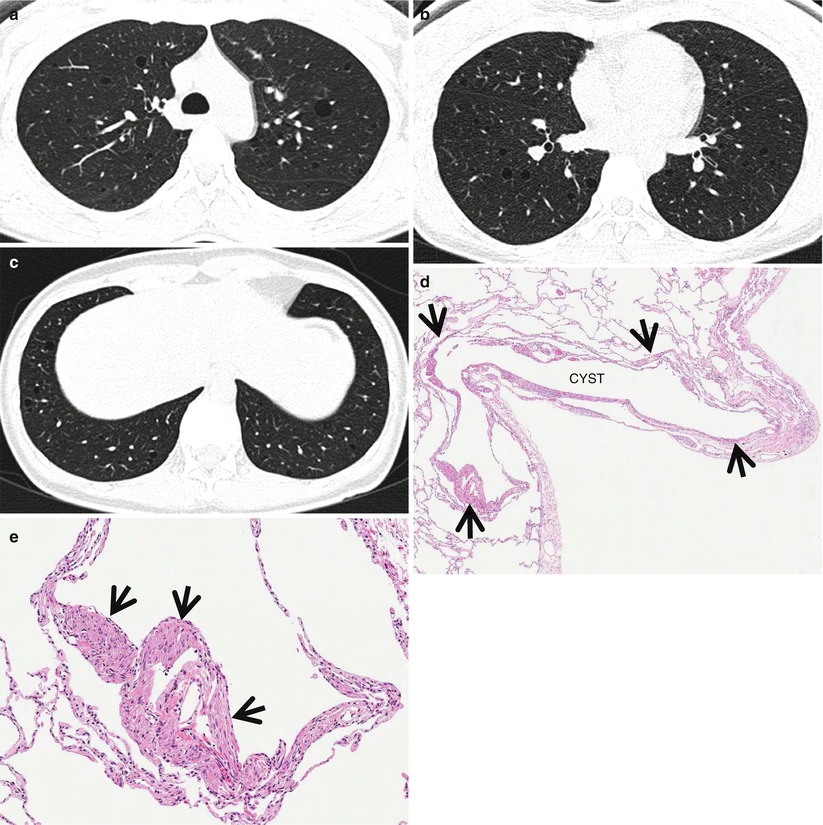

Fig. 23.3

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis in a 37-year-old woman. (a–c) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of aortic arch (a), inferior pulmonary veins (b), and liver dome (c), respectively, show multiple variable-sized air-filled cysts in both lungs. Please note involvement of lung bases that are spared in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. (d) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen depicts a cystic lesion (CYST) and its wall composed of spindle or ovoid smooth muscle cells (arrows). (e) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph discloses clearly cystic wall composed of spindle or ovoid smooth muscle cells (arrows)

Diseases Causing Multiple Cysts

Many diffuse lung diseases may manifest cysts as the primary abnormality [17, 18]. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (Fig. 23.3) and Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) are the most common to present with diffuse lung cysts. Other interstitial lung diseases that may cause multiple cysts include lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) (Fig. 23.4), desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and amyloidosis. Cystic pulmonary metastasis (angiosarcoma) (Figs. 23.5 and 23.6) and Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome also cause multiple pulmonary cysts. Honeycombing cysts in various interstitial lung diseases (usual interstitial pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, asbestosis, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, advanced fibrotic sarcoidosis) also appear as multiple pulmonary cysts (please note section “Cyst” in Chap. 12and section “Honeycombing with Subpleural or Basal Predominance” in Chap. 17).

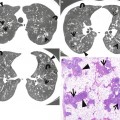

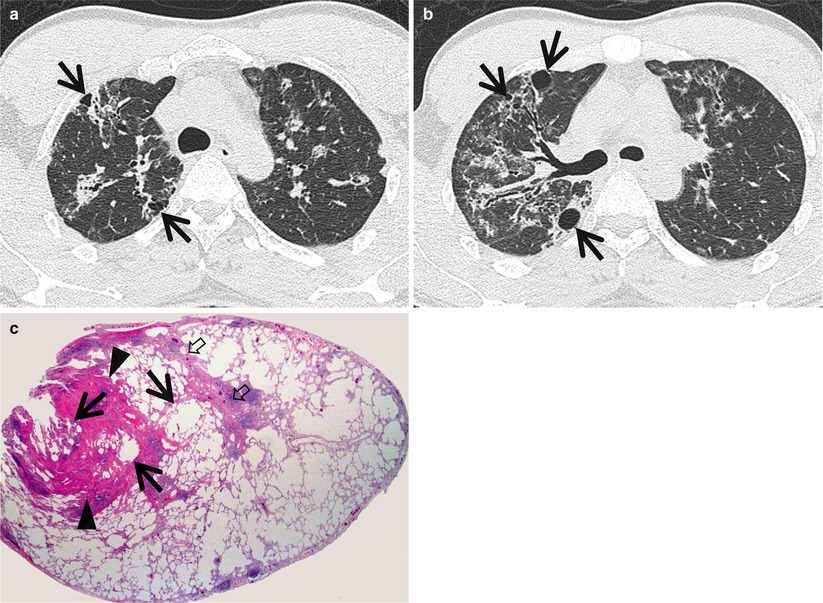

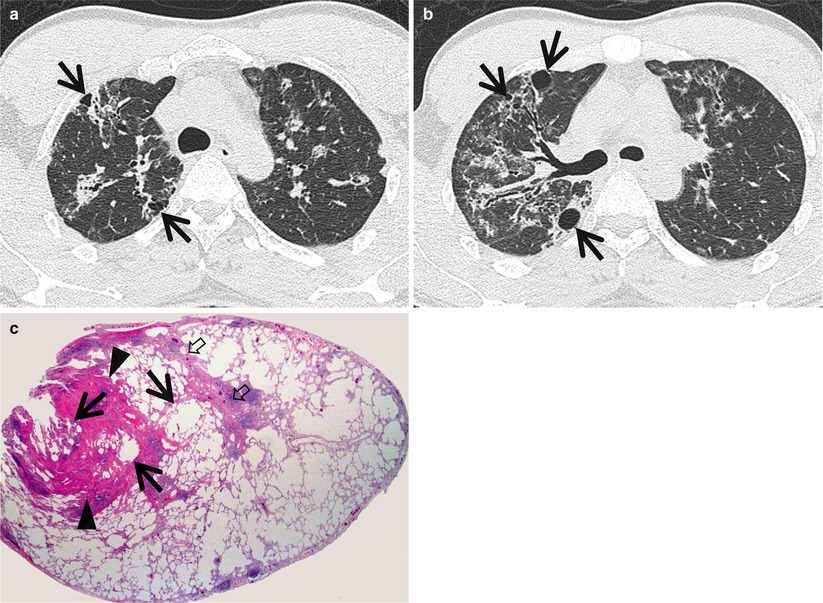

Fig. 23.4

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia in a 37-year-old man with Sjögren’s syndrome. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and right upper lobar bronchus (b), respectively, show ground-glass opacity nodules or ground-glass opacity in both lungs along bronchovascular bundles or along subpleural lungs. Also note cystic lung lesions (arrows). (c) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen depicts peribronchiolar dense fibrosis and scanty lymphocyte aggregations (arrowheads). Such changes are also seen in interlobular septa (open arrows) and subpleural region. Please note cystic changes (arrows) of alveoli associated with bronchiolar fibrosis and inflammation

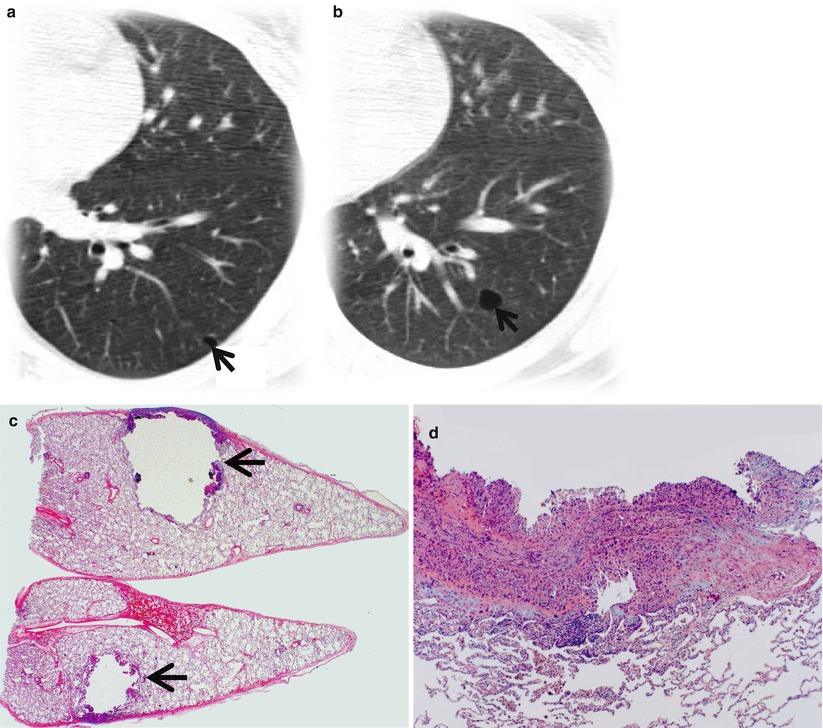

Fig. 23.5

Cystic metastasis in a 20-year-old man with osteogenic sarcoma in right thigh. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of left inferior pulmonary vein (a) and basal segmental bronchi (b), respectively, show cystic lung lesions (arrows). (c) Low-magnification (×4) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen depicts a unilocular cyst with thin wall (arrows) which is composed of metastatic tumor cells. (d) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph discloses cyst wall composed of spindle-shaped pleomorphic tumor cells permeating bronchiolar wall

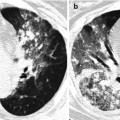

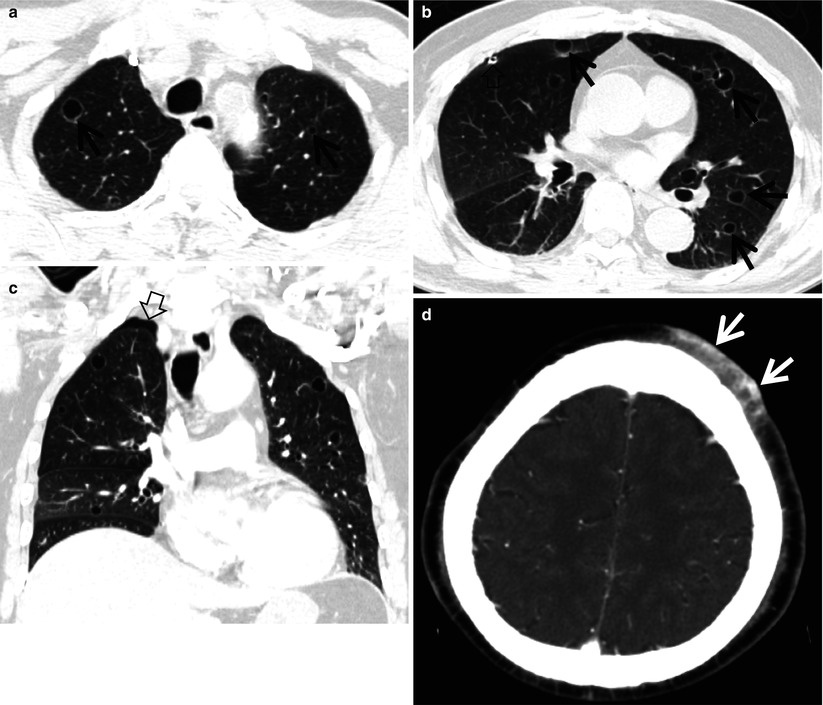

Fig. 23.6

Cystic metastasis in an 82-year-old man with angiosarcoma in his scalp. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scan (5.0-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and arising portion of right middle lobar bronchus (b), respectively, show cystic lung lesions (arrows) in both lungs. A pigtail catheter (open arrow) was inserted in right pleural space in order to evacuate pneumothorax caused by rupture of cystic lung lesions. (c) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) also demonstrates multiple cystic lung lesions. Also note pneumothorax (open arrow) in right apex. (d) Enhanced CT (5.0-mm section thickness) scan of brain depicts a band-like highly enhancing soft tissue tumor (arrows) in left scalp, anteriorly, which turned out to be an angiosarcoma

Distribution

Clinical Considerations

Please note section “Cyst” in Chap. 12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree