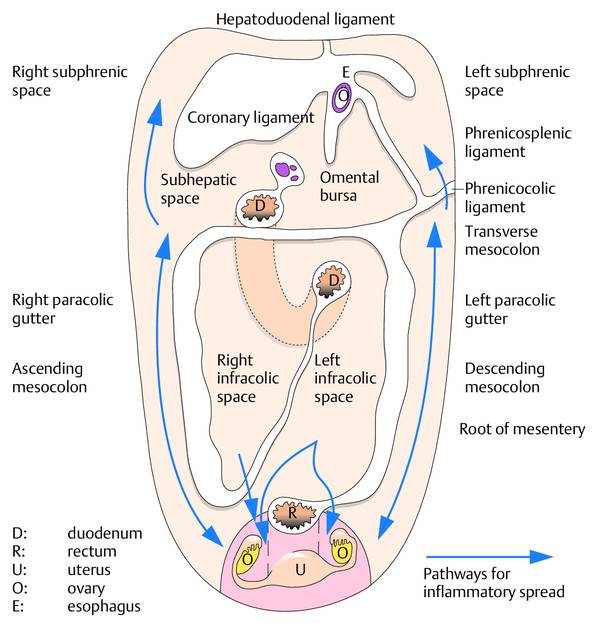

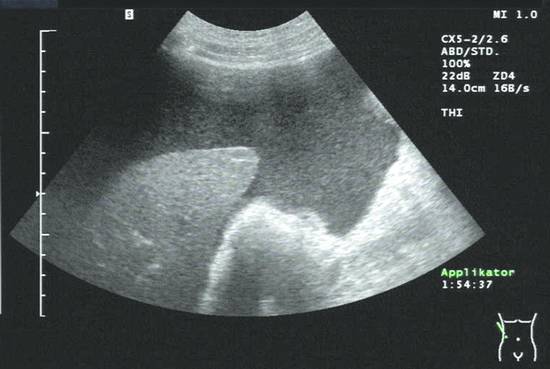

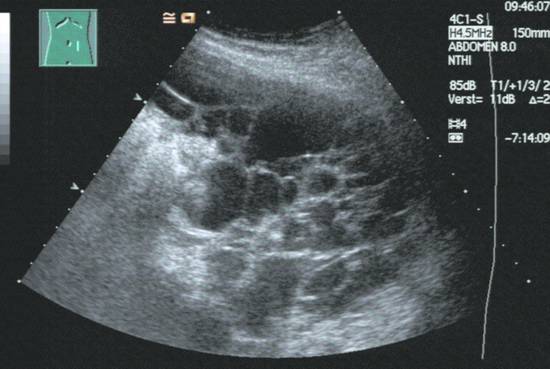

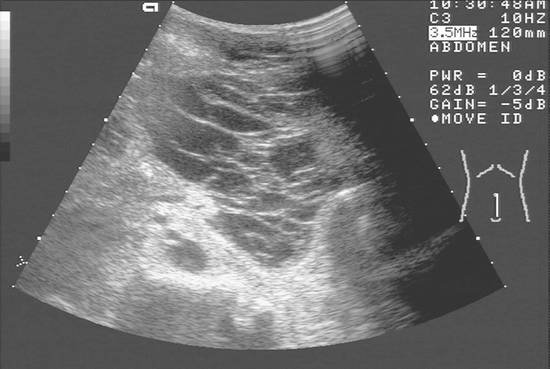

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Paracentesis of Free Abdominal Fluid Free intra-abdominal fluid collections are generally abnormal and require investigation. Peritoneal fluid collections (ascites) are easy to detect with ultrasound. The fluid appears echo-free, may contain internal echoes, and collects at typical sites between the abdominal organs in the peritoneal cavity. The peritoneum is the thin serous membrane that covers the abdominal organs (visceral peritoneum) and also lines the abdominal wall (parietal peritoneum). The space between the visceral and parietal peritoneum is the peritoneal cavity. Normally it is only a potential space that is not visible sonographically, but it may become visible under abnormal conditions. An actual space develops only when fluid or some other substance (tumor, gas) occupies the peritoneal cavity, forming an intraperitoneal mass or collection. Fluid tends to gravitate toward dependent sites, i.e., posterior sites in the supine position and lower abdominal sites in an upright position. An awareness of these sites of predilection aids in the identification of fluids and the compartments they occupy (▶ Fig. 13.1). Fluid moves when a patient is repositioned, gravitating toward the lowest level.1 Sites of predilection for intra-abdominal fluid collections are: Right perihepatic space Left perihepatic space Right subhepatic space (between the right lobe of the liver and the right kidney = Morison pouch) Subphrenic space Perisplenic space Omental bursa Cul-de-sac, perivesical space Between loops of intestine (separation of bowel loops) There are various mechanisms of fluid collection within the peritoneal cavity. They include the hypersecretion of serous fluid by the peritoneum and impaired fluid absorption, which may occur in peritonitis, for example. Fluid may also enter the peritoneal cavity as a result of injury to fluid-containing structures. This would include bleeding into the peritoneal cavity (hemoperitoneum), biliary perforation (intraperitoneal bile leak), and gastrointestinal perforation. Intraperitoneal fluid collections may also result from pressure alterations in the venous system (right heart failure, portal hypertension).2 Ascites formation has a diverse pathogenesis. Differential diagnosis relies mainly on the history, the clinical presentation, the fluid distribution by ultrasound imaging, ultrasound morphology (▶ Table 13.1), and ultimately on ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (US-FNAB). The differential diagnosis of intraperitoneal fluid collections is in ▶ Table 13.2. If the intra-abdominal fluid collection is completely echo-free, contains no floating particles or fibrin strands, and shows no wall irregularities, it is most likely a transudate (▶ Fig. 13.2). This means that laboratory testing of the fluid will show a protein content <30 g/L. Typical examples are found in hepatic cirrhosis and heart failure. Fig. 13.2 Echo-free ascites: transudate due to decompensated hepatic cirrhosis. If the fluid collection in the abdominal cavity is permeated by fine internal echoes or contains septations, it is most likely an exudate. It is also common for ultrasound to show filamentous structures adherent to the lateral abdominal wall or visceral peritoneum. These fibrin strands often show a classic swaying or undulating motion when the patient is repositioned. Examples of exudative ascites are pancreatogenic ascites and purulent peritonitis. Echogenic ascites is also found in peritoneal carcinomatosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in patients with hepatic cirrhosis (▶ Fig. 13.3). Fig. 13.3 Echogenic ascites in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Ascites in portal decompensated hepatic cirrhosis is usually echo-free. The underlying disease is easily diagnosed from the hepatic changes. Irregular liver contours and splenomegaly are the most immediate and reliable signs. On the other hand, the ascites is found to contain fine, floating internal echoes in up to 20% of cases. Associated findings in pronounced cases may include septa, mural fibrin strands, and partially loculated ascites. Clinically, the ascites is refractory to treatment. These are signs of SBP, one of the most frequent complications of cirrhosis. The diagnosis relies on needle aspiration and fluid analysis (determination of granulocyte count or organism identification). Ascites should be investigated by percutaneous aspiration, at least initially and also later in the course if the ascites is refractory to medical treatment. Transudate in decompensated right heart failure is usually a late sign and is observed after or coexisting with pleural effusion (right > left). Besides general clinical manifestations, typical signs at ultrasound are a markedly dilated and stiff inferior vena cava and enlarged hepatic veins (prominent hepatic venous confluence). A protein deficiency (due to varying causes) with a very low plasma albumin level may lead to transudation. This is associated with a detectable thickening of the gallbladder wall (>3 mm). No changes are observed in the hepatic parenchyma or liver vessels. Laboratory tests further advance the diagnosis. Inflammation and infection of the peritoneum may also incite the formation of ascites. Usually this fluid is echogenic and contains fibrin strands and septa (exudate). In cases with moderate hypersecretion due to a viral infection with polyserositis, for example, the ascites may also be echo-free. Severe purulent peritonitis is characterized by echogenic contents and adhesions, matted loops of small bowel, and the frequent presence of gas inclusions (▶ Fig. 13.4). Fig. 13.4 Purulent peritonitis in a patient who had undergone a previous pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. The malignant ascites that develops in peritoneal carcinomatosis may be echogenic to echo-free. The sonographic criteria for differentiating between benign and malignant ascites are described in ▶ Table 13.3. Notably, no signs of hepatic cirrhosis or portal hypertension are observed, and the detection of a possible primary tumor or metastases may point to the malignant cause. Echo-free Internal echoes (echogenic) Septations Echogenic ascites with fine internal echoes, wall irregularities, septa, mesenteric retraction, and solid structures on the peritoneum characterize peritoneal carcinomatosis. Differentiation between benign and malignant ascites is a typical “building block” diagnosis. A single fine-needle aspiration (FNA) provides poor sensitivity (50–60%) in the diagnosis of malignant ascites.1,3–5 Thus if a tumor is suspected, the cytologic examination should be done more than once (at least three times) or a larger initial fluid volume should be centrifuged for analysis. Fresh bleeding into the peritoneal cavity after blunt abdominal trauma, ectopic pregnancy, iatrogenic (interventional) injury, or medication (e.g., anticoagulants) is often echo-free in its initial state. As the hours pass, echogenic internal structures appear in the form of fibrin strands due to initial clotting (▶ Fig. 13.5). The history, clinical presentation, and changing ultrasound findings are diagnostic of intraperitoneal bleeding in 95 to 98% of cases. In the absence of a volume increase (arrested hemorrhage), ultrasound is suitable for follow-up. Over time the clotted blood becomes more organized and initial reabsorption occurs. Portions of the hematoma may reliquefy in some cases. Fig. 13.5 Ascites with internal echoes (fibrin strands and streaks) in the lower abdomen caused by an organizing hemoperitoneum. Exudation into the free abdominal cavity is often observed in the setting of acute or acute recurring pancreatitis. This is more pronounced in necrotizing pancreatitis than in an edematous form. In severe cases all compartments are involved, leading to the complete picture of a pancreatogenic abscess. The abscess may be echo-free, but it is more common to find internal echoes and septa. Fibrin strands are a conspicuous finding on ultrasound (▶ Fig. 13.6). Inflammatory changes in the pancreas itself also contribute to the diagnosis (necrotic changes and other signs of pancreatitis along with typical vascular changes). If the clinical presentation and ultrasound findings in the pancreas are not definitive, FNA will reveal high amylase and lipase levels in the ascites that confirm the pancreatogenic cause. Fig. 13.6 Ascites with internal echoes (fibrin strands and streaks) in the lower abdomen due to necrotizing pancreatitis.

13.1 Peritoneal Cavity

13.2 Sites of Predilection for Intra-abdominal Fluid

13.3 Pathogenesis and Differential Diagnosis of Ascites

Echogenicity

Contents

Ultrasound visualization

Echo-free

Transudate

Clear visualization with good evaluation of surroundings

Exudate

Blood (early phase)

Hypoechoic

Exudate

Clear visualization with moderately good evaluation of surroundings

Blood (late phase)

Bile

Pus

Chyle

Source: based on reference1.

Transudate

Exudate

Blood

Postoperative, traumatic

Hepatic cirrhosis

Peritoneal carcinomatosis

Trauma

Hematoma

Budd–Chiari syndrome

Peritonitis

Iatrogenic

Seroma

Right heart failure

Pancreatitis

Ectopic pregnancy

Bilioma

Inferior vena cava obstruction

Tuberculosis

Coagulopathy

Urinoma

Nephrotic syndrome

Peritoneal dialysis

Ruptured aortic aneurysm

Bowel contents

Mesenteric vein thrombosis

Mesothelioma

Cyst contents

Hypoalbuminemia

Lymphocele (chyloperitoneum)

Source: reference29.

13.4 Specific Indications

13.4.1 Transudate

13.4.2 Exudate

13.4.3 Cirrhosis

13.4.4 Heart Failure

13.4.5 Hypoalbuminemia

13.4.6 Peritonitis

13.4.7 Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

Sonographic features

Benign

Malignant

Echogenicity of ascites:

++

+

+

++

+

++

Mobility

Free

Limited

Loculation

Clear

Loculated, encapsulated

Peritoneal borders

Smooth

Irregular, possible mass

Greater omentum

Thin

Thick, rigid

Mesentery

Free

Retracted

Small bowel loops

“Sea anemone” or “climbing vine” pattern

Matted

Bowel wall

Thin, mobile

Thickened, rigid

Bowel–abdominal wall

Free

Adherent

Other signs

Hepatic cirrhosis, pancreatitis, right heart failure

Metastases, tumor mass on bowel, pancreas, uterus, ovaries

Lymph-node and hepatic metastases

None

++

Source: Meckler U. Ultraschall des Abdomens, 3rd ed. Köln: Deutscher Ärzteverlag; 1992:117, with kind permission of Deutscher Ärzteverlag.27

13.4.8 Hemoperitoneum

13.4.9 Pancreatitis

13.4.10 Other Rare Abdominal Fluid Collections

Tuberculosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree