© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

Luigia Romano and Antonio Pinto (eds.)Imaging of Alimentary Tract Perforation10.1007/978-3-319-08192-2_11. Diagnostic Approach to Alimentary Tract Perforations

(1)

Department of Radiology, Second University of Naples, Piazza Miraglia 2, Naples, 80138, Italy

1.1 Introduction

Alimentary tract perforations represent an emergency and life-threatening condition requiring prompt diagnosis and surgical treatment [1].

Diagnosis depends on clinical suspicion and especially on imaging examinations that allow us to define the presence, the level, and cause of perforation [2].

These details are essential to define an appropriate management and the surgical approach.

Bowel perforation can be spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic in etiology and can occur both in the upper and lower intestines [1–4].

The clinical diagnosis, particularly in the early stage, is difficult as the symptoms may be variable and nonspecific [5].

The standard treatment is prompt surgery, and if the diagnosis and treatment are delayed, the patient morbidity (sepsis and multiorgan failure) results in 75 % and mortality in 30 % [1, 6]. The imaging plays an important role to determine the diagnosis and ensure an appropriate treatment to these patients.

Plain abdominal X-ray still remains the most frequently requested imaging examination in the emergency department even if its role is currently debated; ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) traditionally have been the dominant cross-sectional imaging modalities for evaluating acute thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic conditions; magnetic resonance (MR) is not yet widely used in diagnostic work-up of patients with acute abdominal pain, but can be useful in the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen in specific patients (pregnancy, pediatric patients) [7].

1.2 Clinical Symptoms and Etiology

The clinical symptoms are related to the cause and the site of the perforation, so the clinical presentation is variable. Nevertheless, an “acute abdomen” is usually present [7].

Other clinical manifestations include nausea, vomiting, fever, localized abscess formation, inflammatory mass, fistulas, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Rare complications secondary to perforation are septicemia, portal pyemia or pyogenic abscess, enterovascular fistulas, and even endocarditis.

Usually the pain is initially localized in the suggested site of origin but may move to a different site by the time the patient is examined to culminate – if not promptly treated – in diffuse, poorly localized abdominal pain [8].

The etiology spontaneous, traumatic, or iatrogenic is suggested by the clinical history.

The esophageal perforation is more commonly iatrogenic, caused by endoscopic procedures – dilatation for strictures and achalasia [9] – or by surgical complications [10].

The traumatic etiology, which is less common, can result from penetrating sharp injuries or from gunshot [11].

A spontaneous rupture − 15 % of cases – can be due to intensive vomiting or Boerhaave syndrome [12, 13].

Peptic ulcers are the main cause of gastroduodenal perforation, followed by necrotic or ulcerated malignancies, blunt or penetrating trauma, and iatrogenic causes [1, 2, 8].

The main etiologies for small bowel perforation are inflammatory, infectious, and ischemic conditions, small bowel diverticulitis, mechanical obstruction, trauma, malignancy, iatrogenic causes, and foreign bodies [1, 16].

1.3 Imaging

1.3.1 Plain Abdominal X-Ray

Even if in the American College of Radiology (ACR) appropriateness criteria [18] the enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis is considered the most appropriate examination for patients with fever, non-localized abdominal pain, and no recent surgery, plain radiography remains the most frequently requested examination performed as initial imaging in the assessment of patients who present with acute abdominal pain to the emergency department [7, 19, 20, 21, 22]. Plain abdominal radiograph is widely available and can be easily performed. It can exclude major illness such as bowel obstruction and perforated viscus [7]. However, it should be considered that plain abdominal film exposes the patient to 35 times the radiation dose of a chest X-ray (0.7 mSv) and then its use must be carefully assessed anyway [7].

In the available literature, it is emphasized that plain abdominal X-ray should not be used as a routine investigation in patients with undifferentiated abdominal pain, unless there is clinical suspicion of bowel obstruction [20].

The detection of free intraperitoneal gas on the plain X-ray usually indicates bowel perforation. The reported specificity of plain X-ray for pneumoperitoneum ranges from 50 to 70 % according to some AA [8] and from 53 to 89.2 % according to other AA [23], but the site of perforation is almost never elucidated. It is also reported that pneumoperitoneum or retroperitoneum may be not be detected in up to 49 % of patients [24].

Experimental studies [25] have shown that as little as 1 ml of gas can be detected below the right hemidiaphragm on properly exposed erect chest radiographs [5].

Signs of esophageal perforation can be seen on posteroanterior and lateral plain chest radiographs. Such signs are indirect findings and include pleural effusion, pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, hydrothorax, pneumothorax, and collapse of the lung. If a water-soluble contrast medium is administered, it will reveal a contrast leak in most cases of esophageal perforation [13]; water-soluble contrast should be used instead of barium contrast to avoid barium-related inflammation of mediastinum if there is perforation. If the initial contrast swallowing study is negative, imaging should be repeated after 4–6 h if the clinical suspicion remains [12].

Plain abdominal radiograph is usually performed in upright and supine decubitus; in addition, upright chest films and/or left lateral decubitus abdominal films can also be used (in the detection of small amounts of free air that may be interposed between the free edge of the liver and the lateral wall of the peritoneal cavity). In critically ill patients, the supine decubitus is preferred, with anteroposterior and lateral views of the abdomen and anteroposterior view of the thorax [19].

Supine abdominal radiograph allows detection of moderate or large amounts of free intraperitoneal air, but is insensitive in detecting small amounts of free intraperitoneal air; upright abdominal radiographs are better than supine in showing pneumoperitoneum; however, because the X-ray beam is centered on the mid-abdomen, and the exposure is high, small amounts of free air can be obscured. Left lateral decubitus radiograph of the abdomen can show small amounts of free air if the heavy exposure does not compromise the detection. On upright posteroanterior chest radiograph, the central X-ray beam penetrates air in the superior portion of the subdiaphragmatic recess along its long axis and usually does not burn out small amount of free air. The upright lateral chest radiograph is more sensitive than the posteroanterior chest radiograph in detecting small amounts of pneumoperitoneum as the long axis of X-ray beam can show small air collection that may remain trapped anterior to the liver [5, 8, 19, 26, 27].

Several signs of intraperitoneal free air, direct finding of perforation, were described: in the upright thoracic film, the air in the subdiaphragmatic regions and, on the supine abdominal films, the outlining of various peritoneal reflections between the mesenteric folds.

In other cases, indirect sign of perforation could be visible such as translucent triangle, lucent liver, perihepatic gas collections, Rigler’s sign, and cupola sign, and football and cap of Doge signs can be detected [19, 28–30].

Some AA retain that in the presence of clinical signs of acute abdominal pathology, pneumoperitoneum identified on plain X-ray obviates the need for further imaging and constitutes an indication for laparotomy [31, 32] even if in the majority of cases, further imaging is useful to clarify the site and the etiology of perforation.

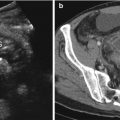

1.3.2 US

Abdominal US examination is particularly indicated in patients in whom radiation should be avoided, as well as children and pregnant woman, being a noninvasive, rapid diagnostic, wide available and low-cost method [33]. It represents an optimal first-line imaging method in emergency department [7, 34].

Some AA reports that US could provide useful information in 56 % of patients with acute abdominal pain, and in another study it is reported that US allows diagnosing or confirming one of the possible differential diagnosis or provides information in 65 % of patients [7].

Diagnostic value of plain X-ray (erect chest film) compared versus US in the detection of pneumoperitoneum in patients with suspected bowel perforation showed US sensitivity of 92 % (versus 78 % of plain abdominal film), a negative predictive value of 39 % (versus 20 %), and specificity of 53 % (versus 53 %) concluding that ultrasound is more sensitive than plain radiography in the diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum [23], even if establishing the cause and location of the perforation is difficult with US [7].

Other AA detected a lower sensitivity for the US if compared with radiography (76 % versus 92 %, respectively), suggesting the use of US only in selected cases [35].

The US examination is conducted with patient in supine position, preferably with the thorax slightly elevated (10–20°) [36]; the linear array transducers (10–12 MHz) are more sensitive than convex transducers(2–5 MHz) in the detection of intraperitoneal free air for their size and shape and for their resolution [36].

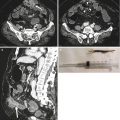

US signs of free intraperitoneal air are represented by echogenic lines or spots with comet-tail reverberation artifacts adjacent to the abdominal wall. These signs are best detected in the prehepatic space using linear probes.

If a pneumoretroperitoneum is present, the detection of the air around the duodenum and the head of the pancreas and especially ventral to the great abdominal vessel lead to the picture of “vanishing” vessels [37].

Indirect signs of bowel wall perforation detectable at US are represented by intraperitoneal free fluid and/or reduced intestinal peristalsis [36].

US main limits are represented by the operator dependence and by the poor cooperation of some patients due to the abdominal pain; obese patients and patients with subcutaneous emphysema are difficult to scan too [36]. Furthermore, US has low sensitivity in the detection of retropneumoperitoneum; so, it should not be considered definitive in excluding a pneumoperitoneum [7, 35].

1.3.3 Multidetector CT (MDCT)

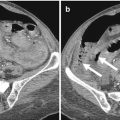

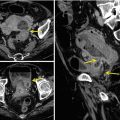

MDCT is considered most valuable imaging technique for identifying the presence, site, and cause of alimentary tract perforations [2, 3, 38, 41, 42] and some AA consider CT as the primary technique for the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain, except in patients clinically suspected for acute cholecystitis – in which US represents the technique of choice [7].

MDCT is superior to single helical CT allowing a rapid execution of the diagnostic exam also in patients with difficulties to perform prolonged breath holds; the thinner collimation may improve the visualization of CT findings suggestive of colonic perforation too [8].

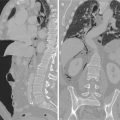

The CT examination in emergency setting is performed with the administration of intravenous (iv) contrast medium and includes the thorax if an esophageal perforation is suspected and/or the entire abdomen, from the dome of the diaphragm to the pelvic floor; the administration of iv contrast medium facilitates a good accuracy and a high level of diagnostic confidence [7].

The range of sensitivity and specificity of MDCT for gastrointestinal perforation is between 80 and 100 % [43]. The CT diagnosis of alimentary tract perforation is based on direct CT findings, such as discontinuity of the bowel wall and the presence of extraluminal air and on indirect CT findings, such as bowel wall thickening, abnormal bowel wall enhancement, abscess, and inflammatory mass adjacent to the bowel [40].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree