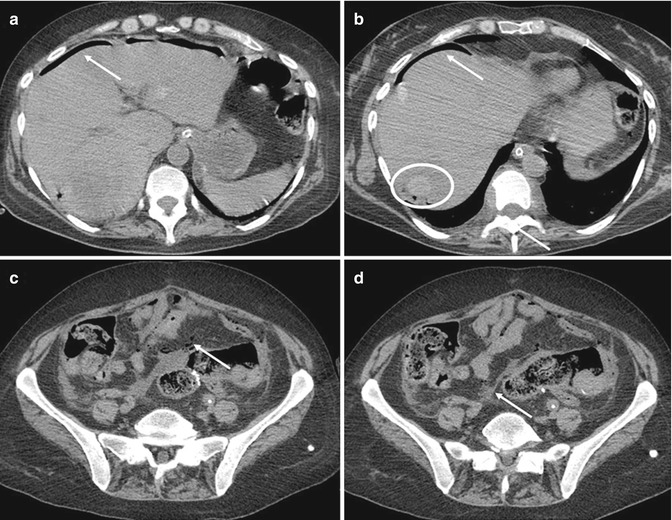

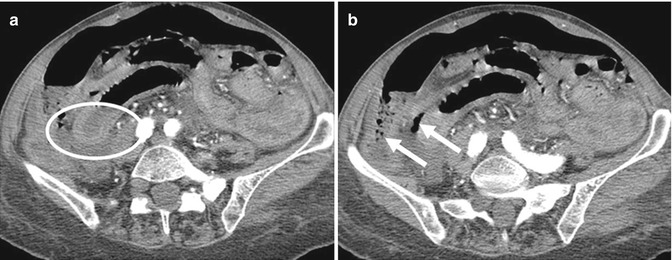

Fig. 14.1

Abdominal CT scan. CT image shows even small amounts of free air (a–d). Additional CT shows the site of the perforation (a, white circle), focal thickening of the bowel wall adjacent to extraluminal gas bubbles (c, white arrows) and streaky density within the mesentery (d, white arrow) ‘dirty fat’ sign (b, white arrow)

The overall accuracy in diagnosing the site of the perforation is 80 % [6]. Yeung et al. [3] also found that the presence of air in both sides of the falciform ligament may differentiate more certainly proximal from distal GIT perforation.

14.2 Foreign Bodies

Generally, the ingestion of foreign bodies occurs involuntarily while eating; meat boluses are the most common foreign bodies ingested in Western countries and fish bones in oriental countries [12–14]. However, in 1 % of cases, it causes complications such as acute abdomen due to intestinal perforation [13]. In some cases, it can cause severe complications and even death; in the USA, 1,500 people die annually from foreign body ingestion [15].

Bowel perforation by a foreign body is less common, as the majority of foreign bodies uneventfully pass to the faeces and only 1 % of them (the sharper and more elongated objects) will perforate the gastrointestinal tract, usually at the level of the ileum [4, 16]. The complications of foreign bodies ingestion with perforation include the formation of localised abdominal abscesses, colorectal, colovesical and enterovascular fistulas, inflammatory masses or omental pseudotumors, pyemia, and endocarditis [4, 17].

In the early patients this condition is more frequent because of persistent two predisposing risk factors for foreign body ingestion: comorbid condition and the use of dentures, because they reduce the sensitivity of the palate [13, 14].

The intestinal tract, where perforations by foreign bodies are most frequent, includes the ileocecal and rectosigmoid regions, because the intestinal lumen narrows and the digestive tract is angulated in these sites. Sites where impaction is most likely include zones with adhesions, areas containing a diverticular process, or surgical anastomoses [13, 14]. Treatment consists of surgery (from primary suture to rectosigmoid resection with colostomy, removal of the foreign body, and abdominal cavity lavage) and antibiotics.

The patient presented at the emergency department with diffuse abdominal pain with peritoneal irritation and vomiting of 24 h duration. Laboratory tests showed generally leukocytosis and increased C-reactive protein. The supine plain abdominal radiograph demonstrated signs of small-bowel obstruction but do not always shows a radio-opaque foreign body or pneumoperitoneum. This finding is not surprising because, for example, fish bones have variable radio-opacity depending on the fish species; in general, the foreign bodies are minimally radio-opaque and can rarely be detected on plain films, especially if they are masse by coexistent inflammatory tissue, fluid, or abscesses [18]. Moreover, signs of pneumoperitoneum are not usually observed in plain films because impaction of the foreign body into the intestinal wall is gradual, allowing the perforation site to seal with omentum or adjacent loops and limiting the amount of gas or fluid in the peritoneal cavity [18]. The use of US makes it possible to identify foreign bodies, even non-radio-opaque bodies such as fish bones and toothpicks, based on their high reflectivity and variable posterior shadowing [4, 19]. MDCT is currently considered the method of choice for the evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain and the depiction of foreign bodies due to MDCT’s ability to generate high-resolution, thin-collimation, multiplanar reconstructions, which allow the GI tract to be examined in all projections.

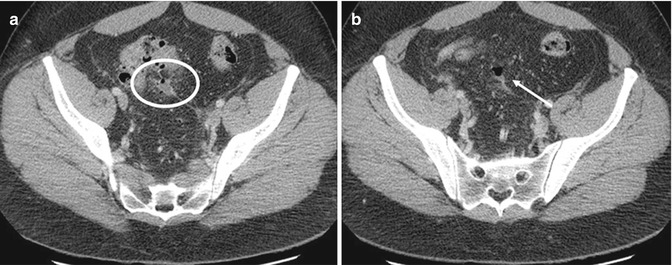

Abdominal CT showed generally a foreign body in the small bowel, with pneumoperitoneum and fluid within the abdominal cavity (Fig. 14.2).

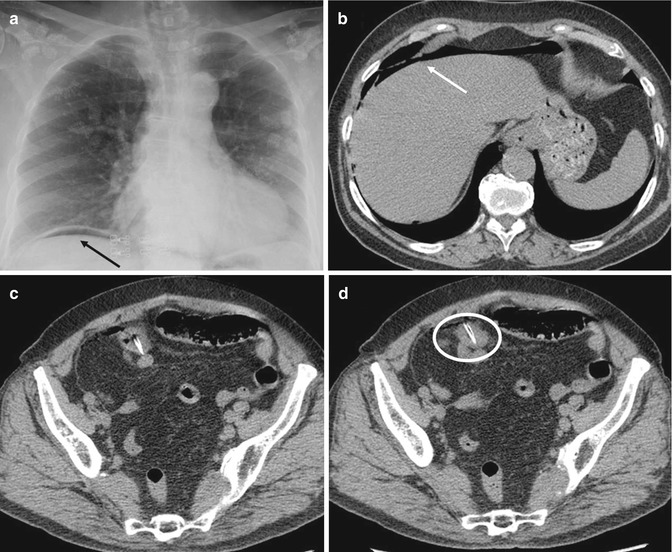

Fig. 14.2

Plain films sign shows gas in the peritoneal cavity (a, black arrows). Abdominal CT confirms pneumoperitoneum (b, white arrow) and shows a foreign body in the small bowel with gas and fluid within the abdominal cavity (c, d, white circle)

14.3 Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer and is also an increasing trend [20, 21]. Computed tomography (CT) has played an important role in the preoperative staging and postoperative surveillance of colon cancer. The recent advances in CT technology provide greater accuracy for the preoperative staging of colorectal cancer. The findings associated with adenocarcinoma of the colorectum generally include asymmetric bowel wall thickening with contrast enhancement or the presence of a soft-tissue mass that frequently leads to luminal narrowing or obstruction.

Common presenting symptoms of CRC include abdominal pain, change in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, anaemia, and weight loss [22]. A less frequent presentation is perforation and abscess formation, which is usually intraperitoneal, but may occasionally be located in extraperitoneal spaces. With contained perforation and abscess formation, the clinical picture can closely resemble complicated diverticulitis, whether on clinical examination or on radiological imaging such as computed tomography (CT) scans. Patients typically present fever, abdominal pain and leukocytosis, and CT scans show a pericolic or intra-abdominal abscess.

Bowel obstruction is the most commonly observed complication of colon cancer. Left-sided colon malignancies are more prone to obstruct the colon lumen than are the right-sided malignancies. This is because the diameter of the left colon is smaller than that of the right colon. CT is a sensitive imaging modality for detecting bowel obstruction, and the multiplanar reconstruction images can provide additional information on the transition point in problematic cases [1]. Identifying the transitional zones and an obstructing lesion on CT, and these usually appear as irregular circumferential thickening of the colon, is important to differentiate this entity from other benign conditions such as adynamic ileus, colonic pseudoobstruction, and stercoral colitis, and all these maladies can present with colonic dilatation.

Perforation in association with a colonic tumour is uncommon as a primary presentation, with incidences ranging from 2.6 % [4] to 10 % [23]. Perforation of the colon can be diagnosed by CT with the demonstration of a focal defect in the colon wall that may be accompanied by a fluid-density abscess, free air, or stranding of the pericolic fat. Abscess formation occurs in 0.3–0.4 % of colonic carcinomas and it is the second most common complication of perforated lesions.

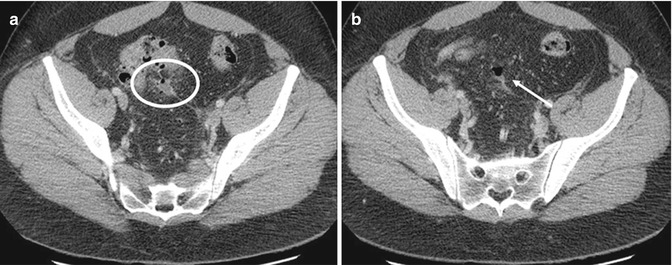

Abscesses commonly remain localised in the paracolic region or may develop into a pelvic abscess, but they can also track along various tissue planes and have been reported to present as a flank abscess, psoas abscess, or even a subcutaneous abscess on the trunk [24]. The location of perforation associated with colonic cancers is most commonly at the tumour site and is due to locally invasive disease causing a breach of integrity of the colonic wall. Perforations can also occur proximally to an obstructing primary lesion, for example, a perforated caecum secondary to a closed loop obstruction with a competent ileocecal valve in an obstructed carcinoma of the sigmoid or descending colon [25, 26]. The location of the tumour is also a factor in the likelihood of perforation and abscess formation. In the right and transverse colon, perforations present twice as commonly as peritonitis compared to abscesses. On the other hand, abscess formation is more common than free perforation in the left colon, and the sigmoid and rectosigmoid are the most frequent locations [23, 27]. It is well documented that perforated colonic carcinoma has a lower 5-year survival rate, in comparison to the uncomplicated colonic cancer undergoing elective resection [28]. It is important that the diagnosis of perforated colonic carcinoma is considered as a differential diagnosis whenever a patient presents with an intra-abdominal abscess with the presumptive diagnosis of perforated diverticular disease. All patients who present with complicated ‘diverticular disease’ and intra-abdominal abscess especially those that do not respond to conservative treatment should be offered surgery with resection of the involved colon and removal of the abscess for histological evaluation (Fig. 14.3).

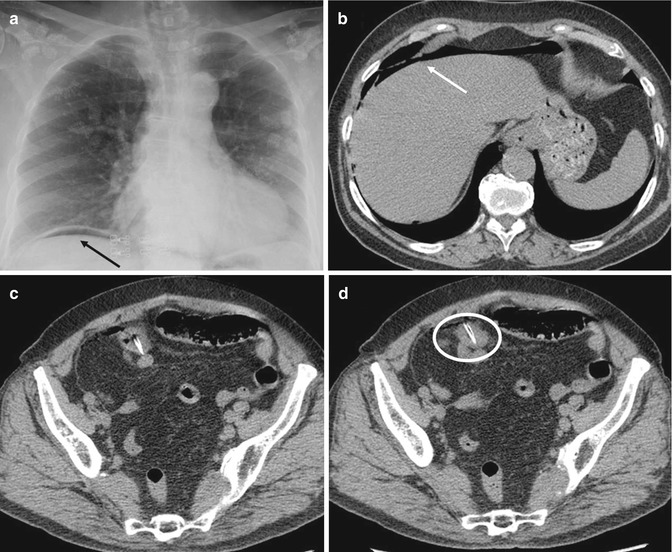

Fig. 14.3

Abdominal CT shows pneumoperitoneum (a, b, white arrows) with liver focal lesion (b, white circle). Axial CT scan shows irregular thickening of descending colon (c, arrow) and pericolic fat stranding (d, arrow). Caudal to colon wall thickening, there are colon wall defect with adjacent peritoneal free fluid and gas (c, arrow). Free perforation was surgically confirmed

14.4 Diverticulitis

Diverticular disease has become more prevalent in Western countries [29, 30]. About 10–25 % of individuals with diverticulosis will develop symptomatic diverticulitis, and of these, 15 % will develop significant complications, such as perforation [31]. Although the absolute prevalence of perforated diverticulitis complicated by generalised peritonitis is low, its importance lies in the significant postoperative mortality, ranging from 4 to 26 % regardless of the surgical strategy selected [31, 32]. Optimal treatment strategies are based on disease severity as classified by Hinchey [33]. The usual management of diverticulitis is based on patients symptomatology as well as CT scan results. Simple diverticulitis can be treated with bowel rest and intravenous antibiotics. Complicated diverticulitis is classified using the Hinchey classification, and management strategies depend on the classification. Hinchey III and IV diverticulitis are indications for laparotomy, washout, and resection of the affected colon.

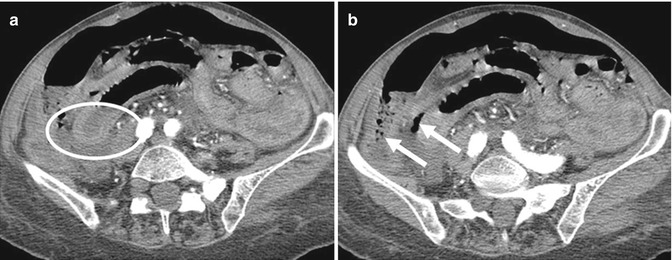

Today, a conservative treatment with antibiotics (and abscess drainage) is advocated for Hinchey 1 and 2 [34]. Patients presenting with perforated diverticulitis with generalised peritonitis (Hinchey 3 and 4) should undergo emergency surgical treatment. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage without resection of the affected bowel segment in patients with purulent peritonitis (Hinchey 3) appears to diminish the morbidity and improve outcome, whereas acute resection should be performer in patients with gross faecal peritonitis (Hinchey stage 4). The combination of free air and intra-abdominal fluid seen on the CT scan correlated well with Hinchey 3 and 4 perforated diverticulitis, and these are the main findings the radiologists used to for the CT based diagnosis of Hinchey 3 or 4 (Fig. 14.4). Preoperative differentiation between Hinchey stage 3 and 4 is not very important, as both need emergency surgical treatment. Nevertheless, it could be useful in deciding on the surgical approach. In case of purulent peritonitis (Hinchey 3), laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and drainage without resection of the affected bowel segment has shown excellent results. In case of faecal peritonitis, laparotomy is recommended for resection of the affected bowel segment.

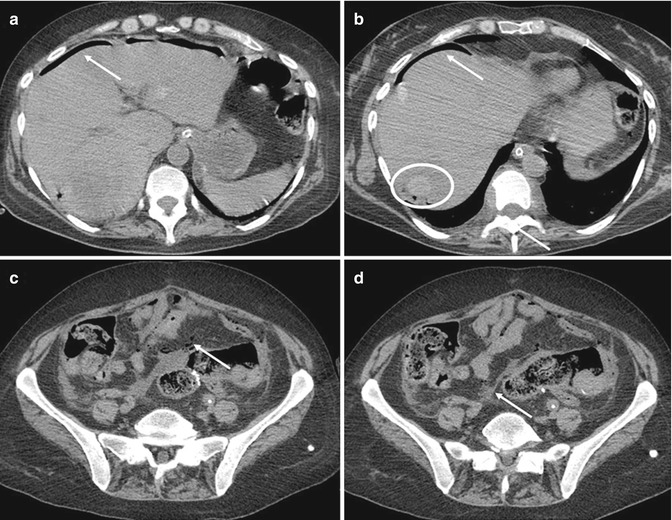

Fig. 14.4

Abdominal CT scan (a, b). The combination of free air (arrow) and intra-abdominal fluid (circle) seen on the CT scan correlated well with Hinchey 3 and 4 perforated diverticulitis

The preoperative differentiation between Hinchey 3 and Hinchey 4 is not possible with CT scanning. Today, computed tomography is the modality of choice in the assessment and management of diverticulitis with its high sensitivity and specificity [35, 36]. With CT-guided percutaneous abscess drainage (PCD), it has also become an important therapeutic modality. In recent years, CT scanning has become the imaging modality of choice to determine the extent of the disease and surgeons tend to rely more frequently on the CT findings to decide upon further treatment [37].

14.5 Ischaemia

The two most common aetiologies that cause vascular impairment of the SB wall leading to perforation are direct vascular occlusion and strangulated SB obstruction [38]. Various vasculitides, characterised by inflammation and necrosis of small systemic blood vessels, including the visceral vessels of the GIT, have been reported rarely as a cause of ischaemic intestinal perforation [39]. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is required for a strangulated bowel. The CT findings suggestive of strangulation include intestinal wall thickening, mural hypoperfusion, blurring of the mesenteric vessels with localised mesenteric fluid, and free peritoneal fluid (Fig. 14.5).

Fig. 14.5

CT scan detects a target appearance of the ischaemic bowel with an inner hyperdense ring due to mucosal hypervascularity, a middle hypodense edematous submucosa, and a normal or slightly thickened muscularis propria. If the vascular impairment persists, CT findings are represented by mural thickening of the involved segments, peritoneal fluid, and mesenteric engorgement (a, circle). In late-stage venous thrombosis, absence of mural enhancement and the presence of fluid and gas may be evident in the sub-peritoneal or peritoneal space (b, arrows)

More specific findings of bowel infarction are lack of bowel wall enhancement, pneumatosis intestinalis, gas in the portal vein, or pneumoperitoneum [38–40].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree