Chapter 17 Diffuse Mediastinal Abnormalities

DIFFUSE MEDIASTINAL ABNORMALITIES

Mediastinal Lipomatosis

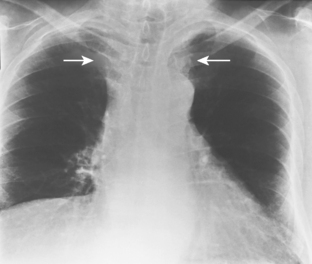

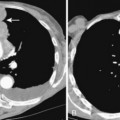

The appearance on chest radiographs and CT depends on the distribution of excess fat deposition. Accumulation of fat in the anterior and superior portions of the mediastinum results in smooth widening of the anterior and superior mediastinal contours as seen on chest radiographs (Fig. 17-1). An important feature is the lack of mass effect on the trachea and esophagus, structures that are often displaced or compressed by other mediastinal abnormalities. Excess fat deposits within the cardiophrenic angles result in cardiophrenic angle “masses,” and excess fat within the paravertebral regions may result in bilateral lateral displacement of the paraspinal lines.

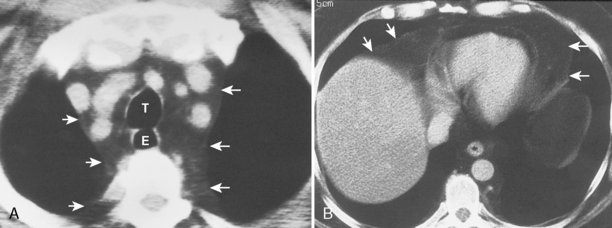

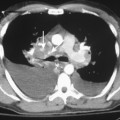

A definitive diagnosis of mediastinal lipomatosis may be made on CT (Fig. 17-2). Fat is recognized on CT by its low CT numbers, which typically vary from −70 to −130 Hounsfield units (HU). Although CT is considered the imaging modality of choice, the diagnosis also can be made by MRI. On MRI, fat demonstrates bright signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Using a fat-suppression sequence results in suppression of the normally bright T1 signal from fat tissue and helps to differentiate it from other tissues with bright T1 signal. An important feature of mediastinal lipomatosis on CT or MRI is a homogeneous appearance of the mediastinal fat. An inhomogeneous appearance, such as the presence of high-attenuation foci within the fat, should raise the suspicion of a superimposed process, such as mediastinal hemorrhage or neoplastic infiltration.

Mediastinitis

Acute Mediastinitis

Acute mediastinitis may occur after esophageal perforation, from extension of an infectious process from thoracic and extrathoracic structures (especially from the neck), and as an infrequent complication of cardiac surgery (Box 17-1). Most cases are caused by esophageal perforation.

Box 17-1 Causes of Acute Mediastinitis

ESOPHAGEAL PERFORATION

Iatrogenic (after esophagoscopy or esophageal dilation)

Impacted foreign body (chicken bone, sharp objects)

Obstructing esophageal neoplasm

Trauma (penetrating trauma more than blunt trauma)

EXTENSION OF INFECTION FROM ADJACENT SPACES

Pharynx (retropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal abscess)

Retroperitoneum (pancreatic pseudocyst)

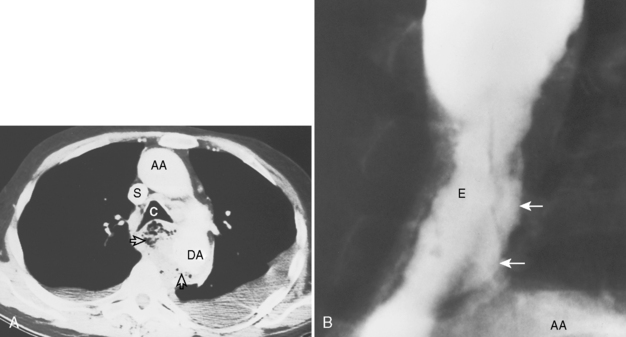

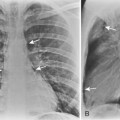

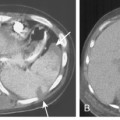

Esophageal Perforation

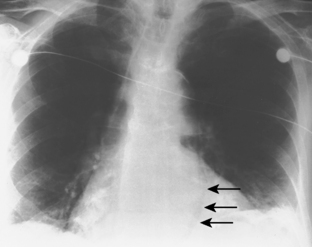

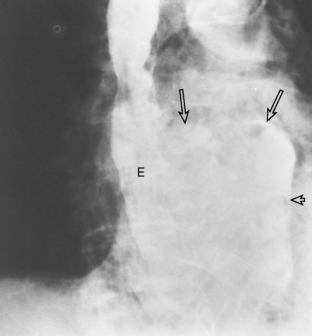

Chest radiographic findings include diffuse widening of the mediastinum and pneumomediastinum (Fig. 17-3). Associated pleural abnormalities are usually left sided and include pneumothorax and empyema. When the diagnosis is delayed, complications may include mediastinal abscess formation and rupture of the abscess into the adjacent bronchus (i.e., esophagobronchial fistula) and pleura (i.e., esophagopleural fistula, often with subsequent development of empyema). The diagnosis of esophageal perforation can be confirmed by fluoroscopic examination after administration of water-soluble contrast, which demonstrates extravasation of contrast at the site of perforation (Fig. 17-4). In complicated cases that have progressed to mediastinal abscess formation, CT may be helpful in identifying the precise location and extent of fluid collections (Fig. 17-5).