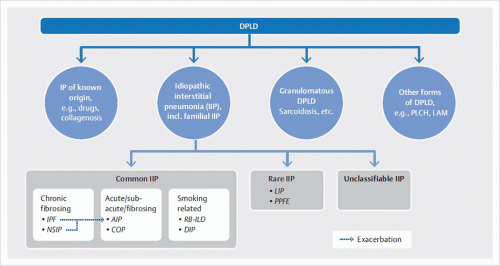

IIPs are a heterogeneous group of rare, noninfectious inflammatory lung diseases of unknown origin. They are typically associated with a pathologic process of the lung interstitium. These diseases are classified in accordance with their histologic findings and are of highly variable prognosis. The main clinical manifestation is gradually progressive dyspnea.

Classification based on the histologic pattern results in ambiguous assignment of clinical disease entities. For example, usual interstitial pneumonia (

UIP) is the underlying histologic pattern of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Furthermore,

UIP pattern is found in pulmonary manifestations of collagen vascular diseases, especially in rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, detection of

UIP pattern is not sufficient for diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; differential diagnosis must exclude other causes of usual interstitial pneumonia. Conversely, a clinically defined disease can produce various histological patterns: in rheumatoid arthritis, for example, the patterns of both usual and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia may occur.

6.1.1 The Role of Radiology

An abnormal

chest radiograph together with a pathologic pulmonary function test usually raises the suspicion of an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

CT is a key component in diagnosis of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases and thus obligatory. The most important contribution of

CT is to identify

UIP pattern; in this case, lung biopsy is not required to establish the diagnosis.

CT is also able to reach a reliable diagnosis for some other diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, such as lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

In the remaining cases,

lung biopsy is usually necessary for a confident clinic-pathologic diagnosis because

CT findings alone do not narrow the differential diagnosis to a single entity.

1 In general, bronchoalveolar lavage makes little contribution to diagnosis but can be useful for differential diagnosis; at times, transbronchial biopsy yields enough lung tissue for histologic diagnosis, especially when performed as cryobiopsy. The advantage of this bronchoscopic procedure is its ability to rule out alternative diagnoses, e.g., sarcoidosis, infection, or malignant disease.

2 Video-assisted thoracoscopic wedge resection is regarded as the standard technique for lung biopsy in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia since it is associated with considerably lower morbidity and mortality compared with open surgical lung biopsy.

3 However, all surgical procedures carry the risk of exacerbating the disease to be diagnosed, especially in pulmonary fibrosis.

CT imaging is indispensable for definition of suitable target zones for biopsy. Histology specimens should be obtained from regions with active disease; it is hardly possible to determine the underlying disease from areas with advanced lung fibrosis.

Diagnostic exploration of diffuse parenchymal lung disease is a dynamic process requiring

multidisciplinary discussion between pneumologists, radiologists, and pathologists (▶

Fig. 6.2). At times, the diagnosis may need to be reevaluated in the light of new clinical aspects or histologic findings in the course of disease.

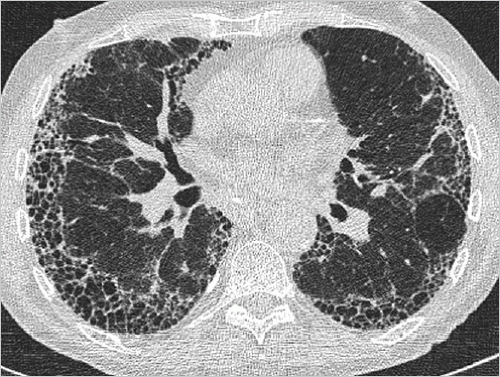

6.1.2 Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (

IPF) is characterized by the histologic pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (

UIP): architectural destruction, fibrosis often with honeycombing, scattered fibroblastic foci, patchy distribution, and involvement of the periphery of the lobule.

1 It predominantly affects patients above the age of 50 years; the median age at time of diagnosis is above 60 years. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis can be diagnosed by excluding any known cause of usual interstitial pneumonia. The disease generally progresses in stages and is quite refractory to treatment. Of all idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, after acute interstitial pneumonia, it has the second worst prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of between 20 and 40%.

In around half of cases, the findings on high-resolution

CT (

HRCT) are so characteristic that they are regarded as pathognomonic of usual interstitial pneumonia. That image pattern is termed in the following as “

UIP pattern.”

HRCT is sufficiently reliable to identify usual interstitial pneumonia through its pathognomonic

CT pattern as presented in ▶

Table 6.2. Lung biopsy is not recommended for confirmation of diagnosis in these cases.

6 The other

HRCT patterns of lung fibrosis (probable

UIP, indeterminate, and alternative diagnosis) are less likely to unlikely (in descending order) to be associated with usual interstitial pneumonia. Therefore, to establish the appropriate diagnosis in the presence of these

HRCT patterns, lung biopsy is recommended by the American Thoracic Society, and endorsed by the European Respiratory Society and the Japanese Respiratory Society and the Latin American Thoracic Society.

6 Contrarily, the Fleischner Society does not recommend lung biopsy in the presence of probable

UIP pattern on

HRCT.

7

6.1.3 Idiopathic Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (

NSIP), like usual interstitial pneumonia, is defined on the basis of its histologic presentation. Two types are distinguished:

Cellular type: This involves mild to moderate chronic interstitial inflammation with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia in the affected areas.

Fibrotic type: This is associated with relatively homogeneous interstitial fibrosis.

Mixed pictures of both types are not uncommon. This

pattern of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is seen in collagen vascular disease, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and in drug-induced lung disease as well as in infections and immunodeficiency settings (e.g., in

HIV infections).

1,9 If no cause can be found, the clinical disease manifestation is regarded as idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. It is thought that a proportion of the cases diagnosed as idiopathic disease are attributable to underlying, hitherto clinically inapparent, undifferentiated collagenosis.

10,11 Such cases do not really constitute idiopathic entities but are pulmonary manifestations of subclinical collagen vascular disease.

The clinical course of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is very variable. The cellular type responds better to treatment than the fibrotic type does and thus has a better prognosis. The mean age of disease onset is around 50 years,

12,13 but nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is found even in children.

14 The most common response to treatment is an unchanging or improved

condition; even virtually complete regression may be observed and relapse of the disease is not uncommon.

12 Progression with a fatal outcome is also possible-in particular, in fibrotic

NSIP.

1

Chest radiography typically shows foci of irregular bilateral, basal reticular opacities.

14 On

CT, characteristic findings are observed:

Ground-glass opacity is a reflection of either active inflammation or fine interstitial fibrosis. Identification of traction bronchiectasis in these areas is consistent with the latter.

CT imaging does not allow for a reliable diagnosis of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia since there is widespread overlap with the

CT features of other diseases. Therefore, biopsy should be considered for a definite diagnosis.

6.1.4 Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

Organizing pneumonia is a common reaction pattern of the lung parenchyma to different pathologic conditions, such as infections or tumors as well as the most diverse physical and chemical stimuli. Lung involvement of different diseases (e.g., collagen vascular diseases and inflammatory bowel diseases) may present as organizing pneumonia.

18 Defective healing

secondary to abscesses or in association with granulomatous polyangiitis or Wegener granulomatosis also manifests as organizing pneumonia.

1 Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (

COP), like other forms of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, is present in settings where no known cause can be identified to explain the histologic pattern of organizing pneumonia.

Typical age of disease onset is around 60 years. The disease course to diagnosis is rather short, usually less than 3 months and is associated with cough and dyspnea to varying degrees. Often, a low respiratory tract infection is initially suspected and unsuccessfully treated with several antibiotics. Diagnostic efforts are continued in the light of persistent pulmonary opacities and ultimately lead to diagnosis of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. The disease generally has a good prognosis and completely regresses within a few weeks in most patients receiving oral steroids. However, recurrences are common during the first 3 months of discontinuing or reducing steroid medication. Lifethreatening disease progression is only very rarely observed.

1 Left untreated, the infiltrates occasionally disappear but are frequently replaced by new infiltrates at other sites.

Chest radiography typically reveals areas of unilateral or bilateral, occasionally also solitary, consolidation. Their location may change over the course of several weeks. In some cases, focal lesions are observed.

1 Less common is a reticulonodular pattern, which is associated with a poorer response to steroids and increased risk of progression to lung fibrosis.

19While cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is not associated with any specific

CT findings, characteristic constellations of findings are common.

20,21,22Unilateral or bilateral consolidation is identified in 90% of cases, in some cases with air bronchogram. Ground-glass opacities are seen mainly in the peripheral regions of consolidations (▶

Fig. 6.8). Most consolidations have irregular margins but only few show spicules.

23 Occasionally, they contain areas of mild cylindrical bronchiectasis. Two distribution patterns can be identified: a peripheral or subpleural pattern (see ▶

Fig. 6.8) and a peribronchial pattern (▶

Fig. 6.9). In 10% of cases, only a single consolidation is found (▶

Fig. 6.10). Small bronchus-associated nodules are seen in half of cases. Around 15% of patients have multiple large nodules with irregular margins, often with air bronchogram.

23The combination of a characteristic clinical course with progressive pulmonary opacities over several weeks despite antibiotics and a characteristic

CT pattern with bilateral subpleural or peribronchial consolidation is highly suggestive of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Nonetheless, a definite diagnosis cannot be made with imaging; in two-thirds of cases,

the diagnosis can be confirmed following histologic examination of the transbronchial

biopsy specimen taken during bronchoscopy, which is indispensable in any case. Otherwise, an additional transthoracic or surgical lung biopsy may be necessary.

6.1.5 Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

Acute interstitial pneumonia (

AIP) is a severe disease with the worst prognosis of all diffuse parenchymal lung diseases. It involves rapidly progressive, diffuse interstitial pneumonia, which presents on histology as diffuse alveolar damage (

DAD).

24,25,26 As in the case of other types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, the findings associated with diffuse alveolar damage are designated as acute interstitial pneumonia if no underlying cause has been identified. The early exudative phase is characterized by diffusely distributed edema, formation of hyaline membranes, and acute interstitial inflammation. In the ensuing organizing phase, loose fibrosis develops, in particular, in the alveolar septa and type II pneumocyte hyperplasia.

25 This is followed by either disease resolution as

restitutio ad integrum or development of lung fibrosis. This histologic pattern is indistinguishable from adult respiratory distress syndrome (

ARDS). It is likely that many of the cases described in 1944 as Hamman-Rich syndrome were, in fact, cases of acute interstitial pneumonia.

25,27Acute interstitial pneumonia predominantly affects patients around the age of 60 years. It shows no gender prevalence and is not associated with smoking. Viral respiratory tract infection symptoms emerge in a few days as severe exertional dyspnea, and

AIP is generally diagnosed within a few weeks. The majority of patients exhibit the clinical picture of adult respiratory distress syndrome and require mechanical ventilation. There is no known effective causal treatment and the mortality rate is at least 50%, with most deaths occurring within the first or second month after disease onset.

24 If the patient survives the disease, lung fibrosis may develop; disease relapse may occur.

1,28,29Chest radiography shows bilateral, patchily distributed opacities with positive air bronchogram.

30 Often the costophrenic angles remain spared. There are no signs of heart failure; pleural effusion is rare. Diffuse consolidation of both lungs increases over time. Later, consolidation resolves as the exudative phase progresses to the organizing phase, with reticular opacity now manifested.

1

Ground-glass opacity develops during the exudative phase.

32 The appearance of traction bronchiectasis and parenchymal distortion marks the transition to the ensuing organizing phase.

6.1.6 Respiratory Bronchiolitis-Interstitial Lung Disease

Respiratory bronchiolitis (

RB) as well as respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease (

RB-ILD) are found only in smokers.

Often, r

espiratory bronchiolitis is diagnosed as an incidental finding on biopsy. It is thought to be present to varying degrees in all active smokers.

34 Histology reveals pigmented macrophages in the first- and second-order respiratory bronchioles.

In general, respiratory bronchiolitis does not cause any symptoms.

35 Only rarely are gradually increasing dyspnea, cough, and restrictive lung function present. Exclusively these symptomatic cases are designated as

respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease. Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease affects active smokers with at least 30 pack years (number of cigarette packs per day multiplied by the number of years smoked) predominantly between the ages of 40 and 50 years. Smoking cessation often improves symptoms; the disease also responds to steroids. However, progression of disease may occur despite smoking cessation in a minority of cases. Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease does not progress to lung fibrosis. The incidence of transition to desquamative interstitial pneumonia is unclear.

Chest radiography appears normal in certain cases. The most common finding in three-quarters of cases is bronchial wall thickening. Ground-glass opacity is found in around two-thirds of cases.

1,36

The most salient features on

CT are signs of bronchiolitis (▶

Fig. 6.12).

The

CT signs can regress on cessation of cigarette smoking or on treatment. Besides, there is often centrilobular emphysema, especially in apical regions.

36,39 It remains unclear if this is a coexistent finding as a sequela of smoking.

34

6.1.7 Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (

DIP) is also associated with cigarette smoking but not as exclusively as respiratory bronchiolitis. Up to 20% of affected patients are nonsmokers. Histology shows an accumulation of pigmented macrophages in the alveoli. It was originally thought that the intra-alveolar cells were desquamated epithelial cells. That explains the misleading disease name, which has also been retained in the new classifications of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Macrophage accumulation is more pronounced than in respiratory bronchiolitis where this is confined to the respiratory bronchioles. The disease regresses in a large proportion of cases on cessation of smoking. Nonetheless, it progresses in one-quarter of patients even on treatment.

40,41,42Chest radiography is not able to reliably visualize desquamative interstitial pneumonia; no pathologic findings are identified in almost one-quarter of diseases diagnosed on biopsy.

1,40,43,44 Otherwise, the predominant findings are patchily distributed, bilateral ground-glass opacities with basal predominance.

CT depicts the characteristic findings of macrophage accumulation, leading to incomplete obliteration of the alveolar lumen and thus to increased parenchymal lung density on

CT (▶

Fig. 6.13). As such, ground-glass opacity is invariably the most salient feature.

45 These changes are found in three-quarters of cases to have basal predominance, in half of cases to have peripheral predominance, and in one-quarter of cases to be irregularly distributed.

1 Intralobular lines are often seen but less pronounced than ground-glass opacities; they are thought to reflect discrete lung fibrosis. Honeycombing is rarely found and when seen is of limited extent.

6.1.8 Rare Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (

LIP) is a lymphoproliferative disease characterized by diffuse pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia. It may be difficult to distinguish from a pulmonary lymphoma on histology. It generally affects patients with immune deficiencies and is also seen in association with several systemic and autoimmune diseases

1:

Rheumatoid arthritis.

Sjögren syndrome.

Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Pernicious anemia.

Hemolytic anemia.

Hypogammaglobulinemia.

Chronic active hepatitis.

Primary biliary cirrhosis.

Myasthenia gravis.

Chest radiography is not useful in differential diagnosis.

CT often depicts characteristic but not pathognomonic findings (▶

Fig. 6.14).

Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (

PPFE) is another pathologically defined rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; to date, there is a paucity of studies on the radiographic or

CT morphology of this disease. Subpleural consolidation and nodules with apical predominance have been described (▶

Fig. 6.15).

47

There are other described histologic patterns that were not regarded as distinct entities of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias in the latest classification; they are suspected rather to represent variants of known idiopathic interstitial pneumonias or other diseases of known origin like collagen vascular diseases, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or drug-induced lung disease.

22 A common feature of these rare diseases is the absence of pathognomonic imaging findings. They are diagnosed through histologic examination of biopsy specimens.