Diffuse Pulmonary Hemorrhage and Pulmonary Vasculitis

W. Richard Webb

DIFFUSE PULMONARY HEMORRHAGE

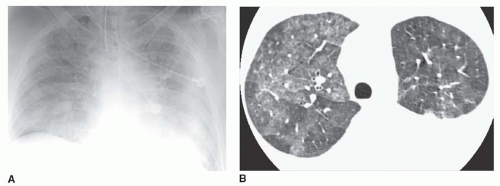

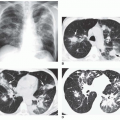

Making a specific diagnosis of pulmonary hemorrhage based on radiographic findings is difficult. Lung consolidation visible radiographically in association with hemoptysis and anemia strongly suggests the diagnosis. However, chest radiographic and CT findings are often nonspecific (Fig. 19-1), and hemoptysis may be lacking even in patients with sufficient hemorrhage to result in anemia.

For the purposes of differential diagnosis, diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage should be distinguished from focal pulmonary hemorrhage occurring as a result of abnormalities such as bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis, active infection (e.g., tuberculosis), chronic infection, neoplasm, pulmonary embolism, or other vascular abnormalities such as arteriovenous fistula.

Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage can result from a variety of diseases (Table 19-1). The differential diagnosis of diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage includes (1) anti- glomerular basement membrane disease (Goodpasture’s syndrome), (2) idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis (IPH), (3) Large vessel vasculitis (including Behçet’s disease), (4) small vessel vasculitis associated with antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody or ANCA (Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis), (5) immune complex-related vasculitis (collagen-vascular diseases, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, mixed cryoglobulinemia), (6) drug reactions, (7) anticoagulation, and (8) thrombocytopenia (see Fig. 19-1).

Goodpasture’s syndrome, vasculitis syndromes, and collagen-vascular diseases are often associated with the combination of pulmonary hemorrhage and renal abnormalities and may be termed pulmonary-renal syndromes.

Radiographic Findings of Diffuse Pulmonary Hemorrhage

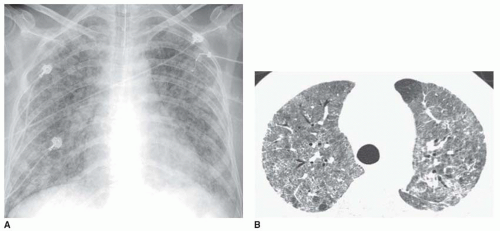

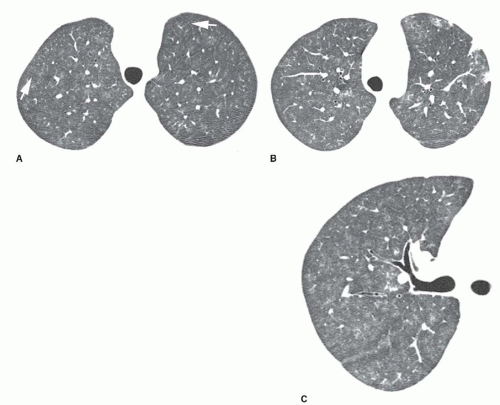

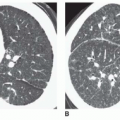

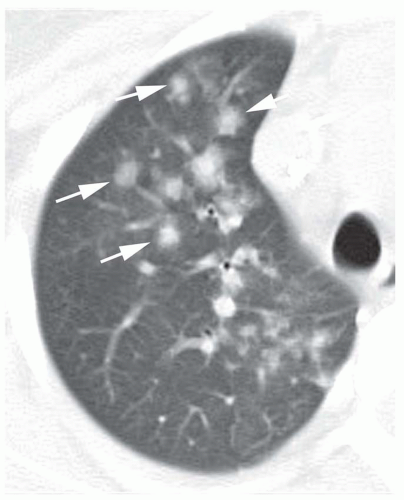

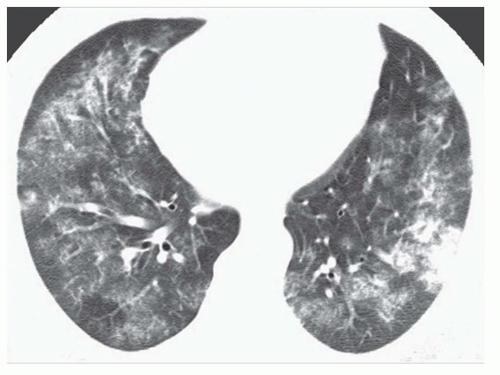

Radiographic findings in diseases causing diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage may be identical. In general, radiographs and high-resolution CT (HRCT) show patchy or diffuse consolidation or ground-glass opacity in the presence of acute hemorrhage (see Figs. 19-1,19-2,19-3,19-4 and 19-5). Ill-defined centrilobular nodules may be seen and predominate in some patients; these are sometimes visible on radiographs but are easiest to see on HRCT (see Figs. 19-2 and 19-5). Chest radiographs

may be normal or show very subtle abnormalities in patients with pulmonary hemorrhage.

may be normal or show very subtle abnormalities in patients with pulmonary hemorrhage.

TABLE 19.1 Causes of Diffuse Pulmonary Hemorrhage | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

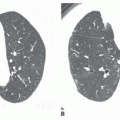

Opacities may be diffuse with uniform lung involvement (see Fig. 19-3) or may show a central and perihilar predominance with relative sparing of the apices, lung periphery, and costophrenic angles (Fig. 19-4). Pleural effusions are not generally associated with pulmonary hemorrhage, although they may be seen in patients with coincident renal failure.

FIG. 19.2. Centrilobular nodules in pulmonary hemorrhage. CT scan in a patient with SLE and pulmonary hemorrhage shows ill-defined centrilobular nodules (arrows). |

Within a few days of an acute episode of hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages begin to accumulate in the interstitium. This occurrence is manifested on chest radiographs by the presence of Kerley’s lines, which may be seen in isolation or in conjunction with residual consolidation or ground-glass opacity. On HRCT, interlobular septal thickening may replace or be seen in association with ground-glass opacity (Fig. 19-5). Unless further hemorrhage occurs,

complete clearing of air-space and interstitial opacities usually occurs within 10 days to 2 weeks of an acute episode of hemorrhage. This is considerably slower than clearing of pulmonary edema, which hemorrhage may closely resemble.

complete clearing of air-space and interstitial opacities usually occurs within 10 days to 2 weeks of an acute episode of hemorrhage. This is considerably slower than clearing of pulmonary edema, which hemorrhage may closely resemble.

FIG. 19.4. Pulmonary hemorrhage in SLE with a parahilar predominance. Patchy ground-glass opacities and consolidation are visible. |

In patients with recurrent episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage, a persistent reticular abnormality may be seen between episodes of bleeding. This reflects interstitial hemosiderin deposition and mild lung fibrosis and has been termed pulmonary hemosiderosis. It may be seen in any cause of recurrent hemorrhage but is particularly common in patients with IPH, as described below.

GOODPASTURE’S SYNDROME

Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease (Goodpasture’s syndrome) most typically occurs in patients aged 20 to 30; men are affected four times as commonly as women (Table 19-2). Hemoptysis, usually mild, and anemia are present in 90%.

Other symptoms include cough, dyspnea, and weakness. Findings of renal disease are usually but not always present, including hematuria, proteinuria, and renal failure. Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies are almost always (95%) present in the serum. These antibodies are directed against type IV collagen and cross-react with alveolar basement membrane. A pulmonary capillaritis is present. Renal biopsy shows glomerulonephritis with linear deposition of IgG in the glomeruli.

Other symptoms include cough, dyspnea, and weakness. Findings of renal disease are usually but not always present, including hematuria, proteinuria, and renal failure. Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies are almost always (95%) present in the serum. These antibodies are directed against type IV collagen and cross-react with alveolar basement membrane. A pulmonary capillaritis is present. Renal biopsy shows glomerulonephritis with linear deposition of IgG in the glomeruli.

TABLE 19.2 Goodpasture’s Syndrome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

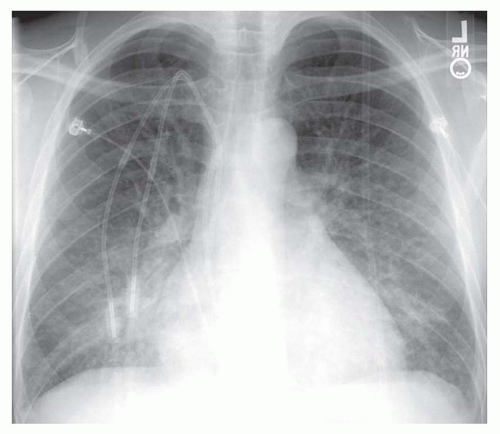

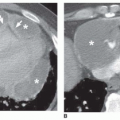

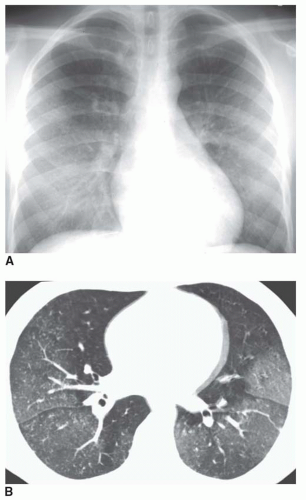

Although plain radiographs may be normal, they usually show diffuse air-space consolidation or ground-glass opacity, typically bilateral and symmetrical and often with a perihilar predominance (Figs. 19-6A and 19-7). HRCT usually shows consolidation or ground-glass opacity and may be abnormal in the face of subtle plain film findings or normal radiographs (see Fig. 19-6B).

FIG. 19.6. Goodpasture’s syndrome. A: Chest radiograph shows a subtle increase in lung opacity. B: HRCT shows patchy ground-glass opacity. |

After an acute episode of hemorrhage, the air-space opacities tend to resolve, being superseded by an interstitial abnormality or septal thickening.

IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY HEMOSIDEROSIS

IPH is a disease of unknown origin characterized by recurrent episodes of diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage without associated glomerulonephritis or a serologic abnormality (Table 19-3). Pathologic findings include alveolar hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and a variable degree of interstitial fibrosis in longstanding cases. IPH most commonly occurs in children under the age of 10 or young adults. In adults, men are affected twice as often as women. IPH is sometimes associated with cow’s milk allergy, thyroid disease, or immunoglobulin A gammopathy. It has recently been reported in infants with exposure to toxic mold (Stachybotrys). Symptoms include cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and anemia. The diagnosis is usually made by exclusion. About a quarter of patients die as a result of respiratory insufficiency or cor pulmonale.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree