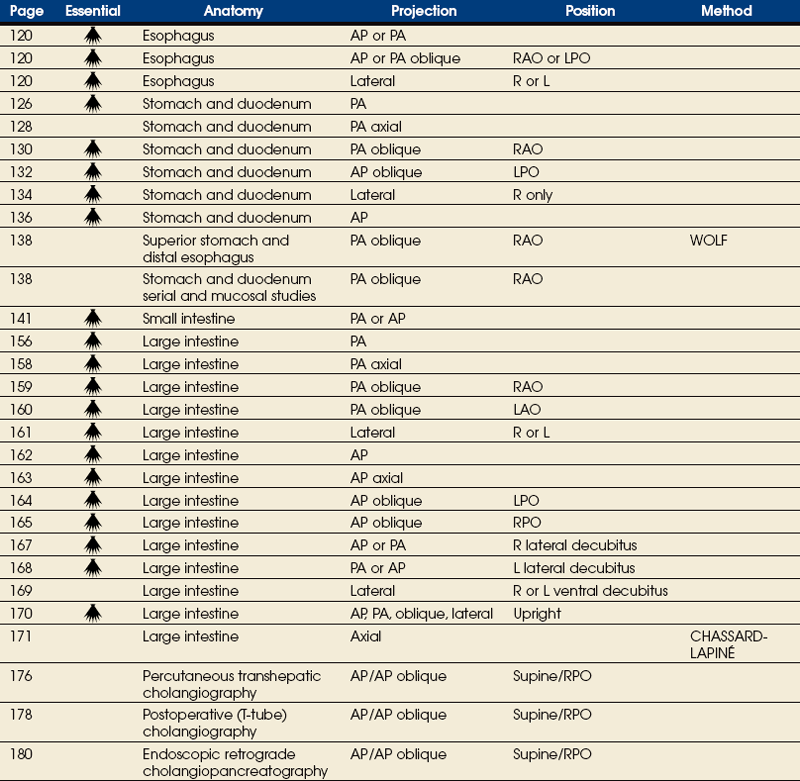

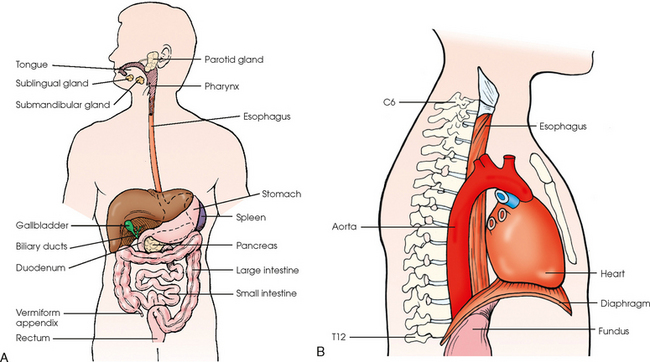

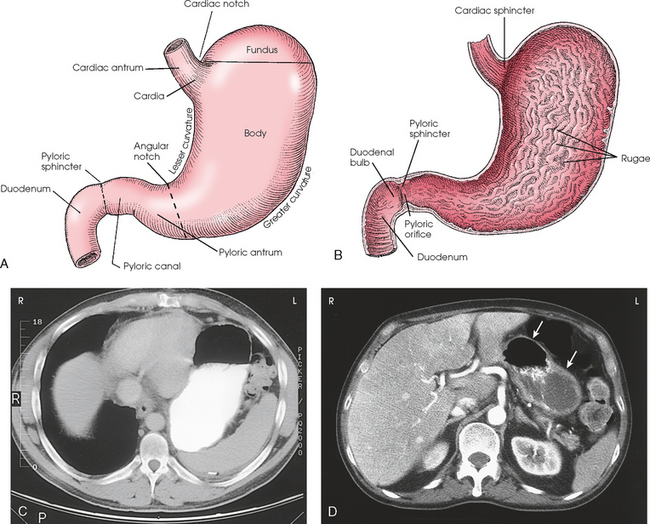

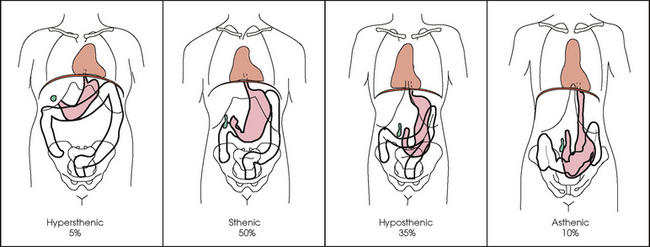

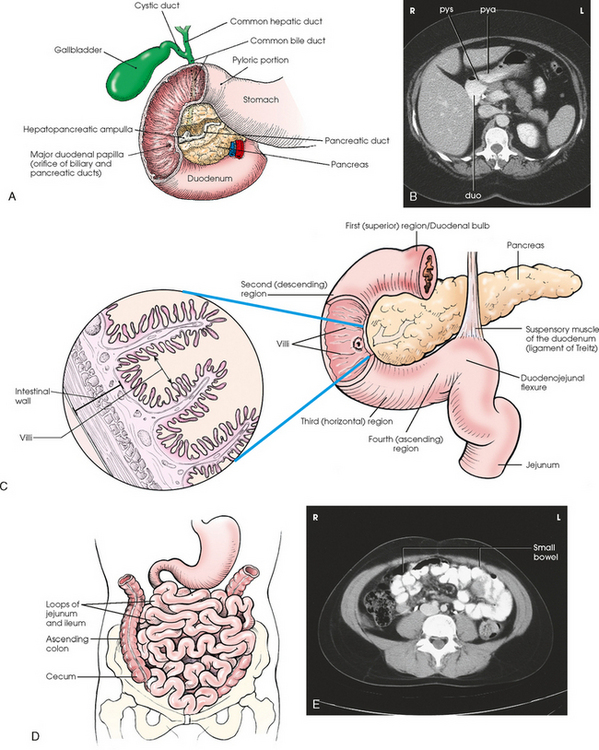

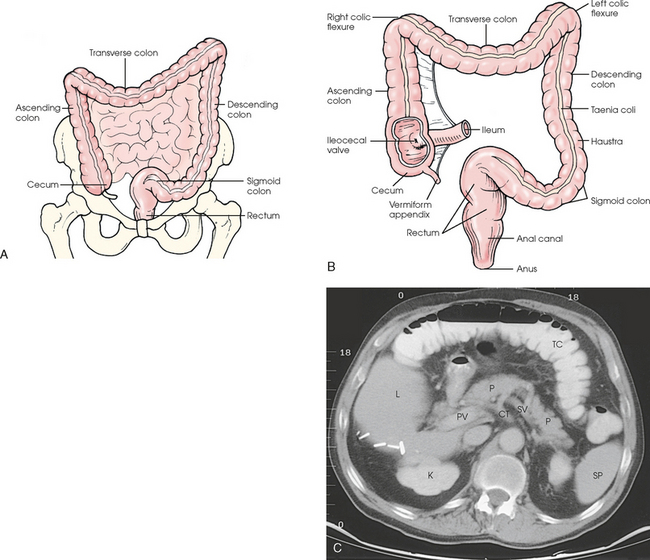

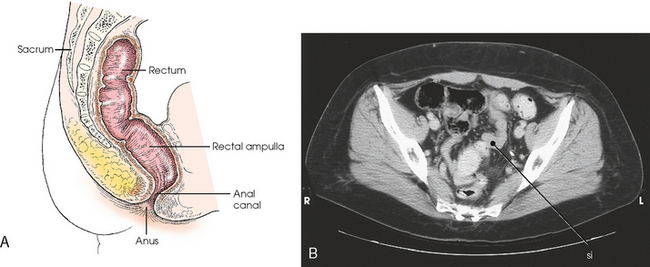

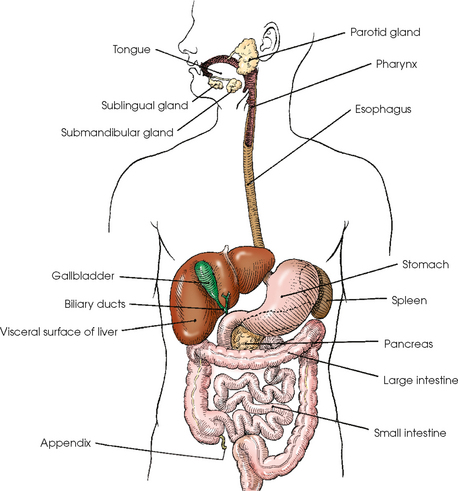

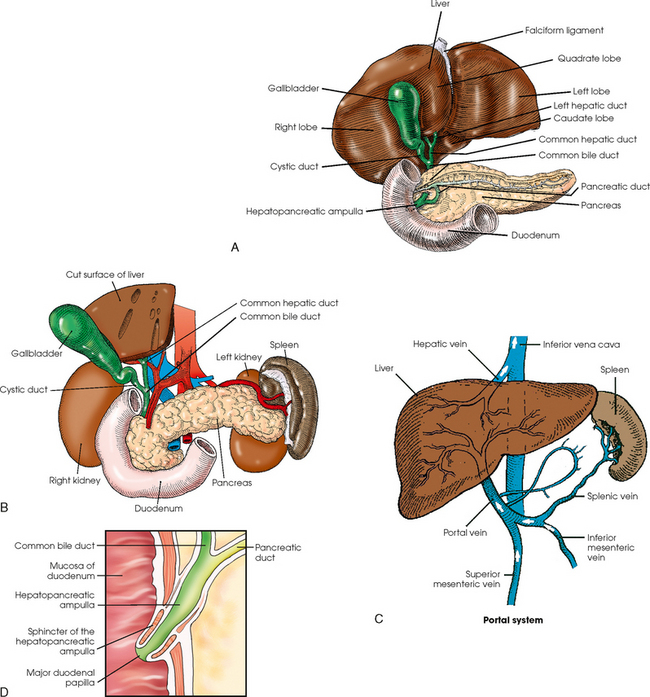

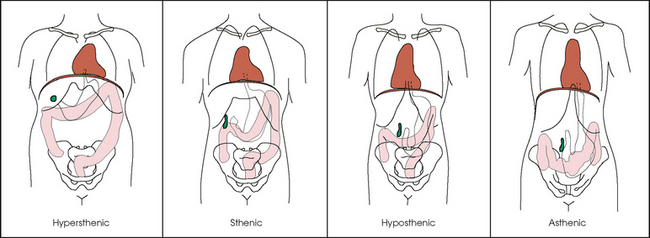

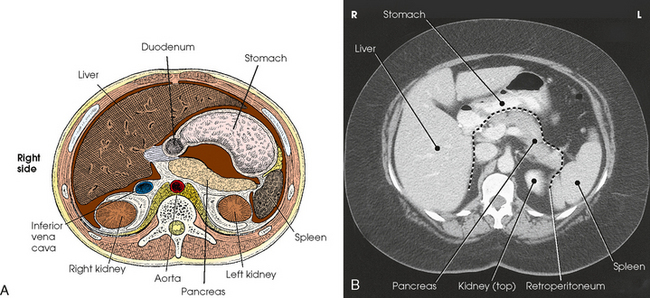

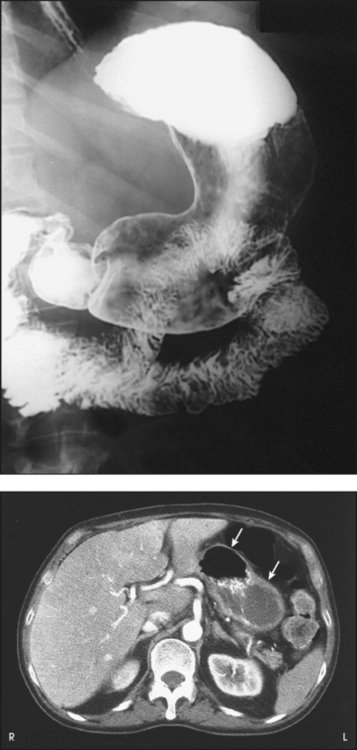

17 The digestive system consists of two parts: the accessory glands and the alimentary canal. The accessory glands, which include the salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, secrete digestive enzymes into the alimentary canal. The alimentary canal is a musculomembranous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. The regions of the alimentary canal vary in diameter according to functional requirements. The greater part of the canal, which is about 29 to 30 ft (8.6 to 8.9 m) long, lies in the abdominal cavity. The component parts of the alimentary canal (Fig. 17-1) are the mouth, in which food is masticated and converted into a bolus by insalivation; the pharynx and esophagus, which are the organs of swallowing; the stomach, in which the digestive process begins; the small intestine, in which the digestive process is completed; and the large intestine, which is an organ of egestion and water absorption that terminates at the anus. The esophagus is a long, muscular tube that carries food and saliva from the laryngopharynx to the stomach (see Fig. 17-1). The adult esophagus is approximately 10 inches (24 cm) long and ¾ inch (1.9 cm) in diameter. Similar to the rest of the alimentary canal, the esophagus has a wall composed of four layers. Beginning with the outermost layer and moving in, the layers are as follows: The esophagus lies in the midsagittal plane. It originates at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra, or the upper margin of the thyroid cartilage. The esophagus enters the thorax from the superior portion of the neck. In the thorax, the esophagus passes through the mediastinum, anterior to the vertebral bodies and posterior to the trachea and heart (see Fig. 17-1, B). In the lower thorax, the esophagus passes through the diaphragm at T10. Inferior to the diaphragm, the esophagus curves sharply left, increases in diameter, and joins the stomach at the esophagogastric junction, which is at the level of the xiphoid tip (T11). The expanded portion of the terminal esophagus, which lies in the abdomen, is called the cardiac antrum. The stomach is the dilated, saclike portion of the digestive tract extending between the esophagus and the small intestine (Fig. 17-2). Its wall is composed of the same four layers as the esophagus. The stomach is divided into the following four parts: The entrance to and the exit from the stomach are each controlled by a muscle sphincter. The esophagus joins the stomach at the esophagogastric junction through an opening termed the cardiac orifice. The muscle controlling the cardiac orifice is called the cardiac sphincter. The opening between the stomach and the small intestine is the pyloric orifice, and the muscle controlling the pyloric orifice is called the pyloric sphincter. The size, shape, and position of the stomach depend on body habitus and vary with posture and the amount of stomach contents (Fig. 17-3). In persons with a hypersthenic habitus, the stomach is almost horizontal and is high, with its most dependent portion well above the umbilicus. In persons with an asthenic habitus, the stomach is vertical and occupies a low position, with its most dependent portion extending well below the transpyloric, or interspinous, line. Between these two extremes are the intermediate types of bodily habitus with corresponding variations in the shape and position of the stomach. The habitus of 85% of the population is either sthenic or hyposthenic. Radiographers should become familiar with the various positions of the stomach in the different types of body habitus so that accurate positioning of the stomach is ensured. The small intestine is divided into the following three portions: The duodenum is 8 to 10 inches (20 to 24 cm) long and is the widest portion of the small intestine (Fig. 17-4). It is retroperitoneal and relatively fixed in position. Beginning at the pylorus, the duodenum follows a C-shaped course. Its four regions are described as the first (superior), second (descending), third (horizontal or inferior), and fourth (ascending) portions. The segment of the first portion is called the duodenal bulb because of its radiographic appearance when it is filled with an opaque contrast medium. The second portion is about 3 or 4 inches (7.6 to 10 cm) long. This segment passes inferiorly along the head of the pancreas and in close relation to the undersurface of the liver. The common bile duct and the pancreatic duct usually unite to form the hepatopancreatic ampulla, which opens on the summit of the greater duodenal papilla in the duodenum. The third portion passes toward the left at a slight superior inclination for a distance of about 2½ inches (6 cm) and continues as the fourth portion on the left side of the vertebrae. This portion joins the jejunum at a sharp curve called the duodenojejunal flexure and is supported by the suspensory muscle of the duodenum (ligament of Treitz). The duodenal loop, which lies in the second portion, is the most fixed part of the small intestine and normally lies in the upper part of the umbilical region of the abdomen; however, its position varies with body habitus and with the amount of gastric and intestinal contents. The large intestine begins in the right iliac region, where it joins the ileum of the small intestine, forms an arch surrounding the loops of the small intestine, and ends at the anus (Fig. 17-5). The large intestine has four main parts, as follows: The colon is subdivided into ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid portions. The ascending colon passes superiorly from its junction with the cecum to the undersurface of the liver, where it joins the transverse portion at an angle called the right colic flexure (formerly hepatic flexure). The transverse colon, which is the longest and most movable part of the colon, crosses the abdomen to the undersurface of the spleen. The transverse portion makes a sharp curve, called the left colic flexure (formerly splenic flexure), and ends in the descending portion. The descending colon passes inferiorly and medially to its junction with the sigmoid portion at the superior aperture of the lesser pelvis. The sigmoid colon curves to form an S-shaped loop and ends in the rectum at the level of the third sacral segment. The rectum extends from the sigmoid colon to the anal canal. The anal canal terminates at the anus, which is the external aperture of the large intestine (Fig. 17-6). The rectum is approximately 6 inches (15 cm) long. The distal portion, which is about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long, is constricted to form the anal canal. Just above the anal canal is a dilation called the rectal ampulla. Following the sacrococcygeal curve, the rectum passes inferiorly and posteriorly to the level of the pelvic floor and bends sharply anteriorly and inferiorly into the anal canal, which extends to the anus. The rectum and anal canal have two AP curves; this fact must be remembered when an enema tube is inserted. The size, shape, and position of the large intestine vary greatly, depending on body habitus (see Fig. 17-3). In hypersthenic patients, the large intestine is positioned around the periphery of the abdomen and may require more radiographs to show its entire length. The large intestine of asthenic patients, which is bunched together and positioned low in the abdomen, is at the other extreme. The liver, the largest gland in the body, is an irregularly wedge-shaped gland. It is situated with its base on the right and its apex directed anteriorly and to the left (Fig. 17-7). The deepest point of the liver is the inferior aspect just above the right kidney. The diaphragmatic surface of the liver is convex and conforms to the undersurface of the diaphragm. The visceral surface is concave and molded over the viscera on which it rests. Almost all of the right hypochondrium and a large part of the epigastrium are occupied by the liver. The right portion extends inferiorly into the right lateral region as far as the fourth lumbar vertebra, and the left extremity extends across the left hypochondrium. At the falciform ligament, the liver is divided into a large right lobe and a much smaller left lobe. Two minor lobes are located on the medial side of the right lobe: the caudate lobe on the posterior surface and the quadrate lobe on the inferior surface (Fig. 17-8, A). The hilum of the liver, called the porta hepatis, is situated transversely between the two minor lobes. The portal vein and the hepatic artery, both of which convey blood to the liver, enter the porta hepatis and branch out through the liver substance (see Fig. 17-8, C). The portal vein ends in the sinusoids, and the hepatic artery ends in capillaries that communicate with sinusoids. In addition to the usual arterial blood supply, the liver receives blood from the portal system. The biliary, or excretory, system of the liver consists of the bile ducts and gallbladder (see Fig. 17-8). Beginning within the lobules as bile capillaries, the ducts unite to form larger and larger passages as they converge, finally forming two main ducts, one leading from each major lobe. The two main hepatic ducts emerge at the porta hepatis and join to form the common hepatic duct, which unites with the cystic duct to form the common bile duct. The hepatic and cystic ducts are each about 1½ inches (3.8 cm) in length. The common bile duct passes inferiorly for a distance of approximately 3 inches (7.6 cm). The common bile duct joins the pancreatic duct, and they enter together or side by side into an enlarged chamber known as the hepatopancreatic ampulla, or ampulla of Vater. The ampulla opens into the descending portion of the duodenum. The distal end of the common bile duct is controlled by the choledochal sphincter as it enters the duodenum. The hepatopancreatic ampulla is controlled by a circular muscle known as the sphincter of the hepatopancreatic ampulla, or sphincter of Oddi. During interdigestive periods, the sphincter remains in a contracted state, routing most of the bile into the gallbladder for concentration and temporary storage; during digestion, it relaxes to permit the bile to flow from the liver and gallbladder into the duodenum. The hepatopancreatic ampulla opens on an elevation on the duodenal mucosa known as the major duodenal papilla. The gallbladder is a thin-walled, more or less pear-shaped, musculomembranous sac with a capacity of approximately 2 oz. The gallbladder concentrates bile by absorption of the water content; stores bile during interdigestive periods; and, by contraction of its musculature, evacuates the bile during digestion. The muscular contraction of the gallbladder is activated by a hormone called cholecystokinin. This hormone is secreted by the duodenal mucosa and released into the blood when fatty or acid chyme passes into the intestine. The gallbladder consists of a narrow neck that is continuous with the cystic duct; a body or main portion; and a fundus, which is its broad lower portion. The gallbladder is usually lodged in a fossa on the visceral (inferior) surface of the right lobe of the liver, where it lies in an oblique plane inferiorly and anteriorly. Measuring about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in width at its widest part and 3 to 4 inches (7.5 to 10 cm) long, the gallbladder extends from the lower right margin of the porta hepatis to a variable distance below the anterior border of the liver. The position of the gallbladder varies with body habitus, being high and well away from the midline in hypersthenic persons and low and near the spine in asthenic persons (Fig. 17-9). The gallbladder is sometimes embedded in the liver and frequently hangs free below the inferior margin of the liver. The pancreas is an elongated gland situated across the posterior abdominal wall. Extending from the duodenum to the spleen (Fig. 17-10; see Fig. 17-8), the pancreas is about 5½ inches (14 cm) long and consists of a head, neck, body, and tail. The head, which is the broadest portion of the organ, extends inferiorly and is enclosed within the curve of the duodenum at the level of the second or third lumbar vertebra. The body and tail of the pancreas pass transversely behind the stomach and in front of the left kidney, with the narrow tail terminating near the spleen. The pancreas cannot be seen on plain radiographic studies. DIGESTIVE SYSTEM, ALIMENTARY CANAL *kVp values are for a three-phase, 12-pulse generator or high frequency. †Relative doses for comparison use. All doses are skin entrance for average adult at cm indicated.

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Alimentary Canal

Digestive System

Esophagus

Stomach

Small Intestine

Large Intestine

Liver and Biliary System

Pancreas and Spleen

EXPOSURE TECHNIQUE CHART ESSENTIAL PROJECTIONS

SUMMARY OF PATHOLOGY

Condition

Definition

Achalasia

Failure of smooth muscle of alimentary canal to relax

Appendicitis

Inflammation of the appendix

Barrett esophagus

Peptic ulcer of lower esophagus, often with stricture

Bezoar

Mass in the stomach formed by material that does not pass into the intestine

Biliary stenosis

Narrowing of bile ducts

Carcinoma

Malignant new growth composed of epithelial cells

Celiac disease or sprue

Malabsorption disease caused by mucosal defect in the jejunum

Cholecystitis

Acute or chronic inflammation of gallbladder

Choledocholithiasis

Calculus in common bile duct

Cholelithiasis

Presence of gallstones

Colitis

Inflammation of the colon

Diverticulitis

Inflammation of diverticula in the alimentary canal

Diverticulosis

Diverticula in the colon without inflammation or symptoms

Diverticulum

Pouch created by herniation of the mucous membrane through the muscular coat

Esophageal varices

Enlarged tortuous veins of lower esophagus, resulting from portal hypertension

Gastritis

Inflammation of lining of stomach

Gastroesophageal reflux

Backward flow of stomach contents into the esophagus

Hiatal hernia

Protrusion of the stomach through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm

Hirschsprung disease or congenital aganglionic megacolon

Absence of parasympathetic ganglia, usually in the distal colon, resulting in the absence of peristalsis

Ileus

Failure of bowel peristalsis

Inguinal hernia

Protrusion of the bowel into the groin

Intussusception

Prolapse of a portion of the bowel into the lumen of an adjacent part

Malabsorption syndrome

Disorder in which subnormal absorption of dietary constituents occurs

Meckel diverticulum

Diverticulum of the distal ileum, similar to the appendix

Pancreatitis

Acute or chronic inflammation of the pancreas

Pancreatic pseudocyst

Collection of debris, fluid, pancreatic enzymes, and blood as a complication of acute pancreatitis

Polyp

Growth or mass protruding from a mucous membrane

Pyloric stenosis

Narrowing of pyloric canal causing obstruction

Regional enteritis or Crohn disease

Inflammatory bowel disease, most commonly involving the distal ileum

Ulcer

Depressed lesion on the surface of the alimentary canal

Ulcerative colitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access