Chapter 9 Diseases of Altered Immunologic Activity

IMMUNE REACTIONS

There are four basic types of immunologic reaction, all of which may be responsible for diseases in the lung. These reactions are not mutually exclusive, and the development of one type may be accompanied by the simultaneous or subsequent development of another (Box 9-1).

GOODPASTURE’S SYNDROME

Characteristics

Goodpasture’s syndrome (Box 9-2) is a disorder of unknown origin that is characterized by repeated episodes of pulmonary hemorrhage, iron deficiency anemia, and glomerulonephritis. It is often rapidly progressive. The immunopathologic nature of the disease is apparent because of the linear deposits of immunoglobulins, which can be demonstrated in the glomerular basement membrane and alveolar septa.

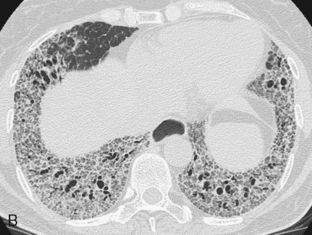

Radiographic Features

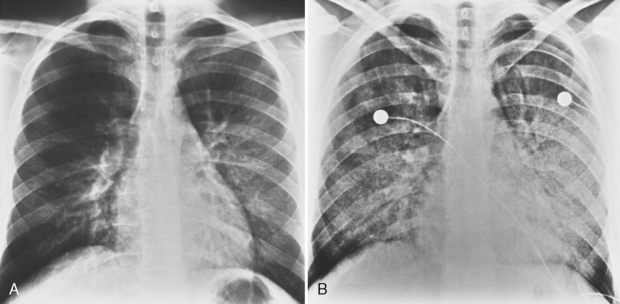

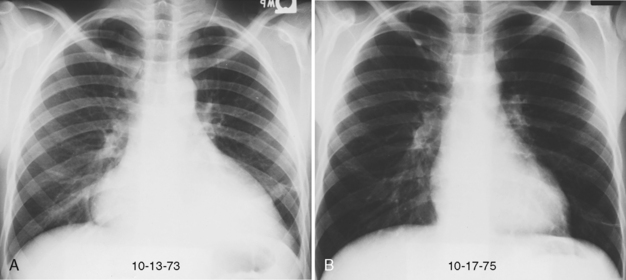

The classic radiographic appearance of Goodpasture’s syndrome consists of diffuse, homogeneous consolidation or alveolar opacities distributed fairly uniformly throughout all lung zones (Fig. 9-1). These changes are characteristic of the early stages of the disease and the development of acute pulmonary hemorrhage. Although the radiographic pattern is similar to that of cardiogenic pulmonary edema, conspicuously absent features are cardiomegaly, Kerley B lines, and pleural effusions. In the later stages, the changes depend on the time sequence and the number of hemorrhages that have occurred in the past. The alveolar consolidation seen during the acute episode may resolve in 2 to 3 days. Irregular or linear opacities often persist for an extended period. If bleeding is continuous or repetitive, these linear and occasionally nodular opacities become permanent as increasing amounts of hemosiderin are deposited within the interstitial tissue. Goodpasture’s syndrome must be differentiated from pulmonary hemorrhage due to other causes, such as idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage (i.e., hemosiderosis) and numerous causes of vasculitis. Hemorrhage may occur rarely in patients receiving systemic anticoagulants.

CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASES

Rheumatoid Disease

Rheumatoid Pleurisy

Pleural involvement is the most common thoracic manifestation of rheumatoid disease (Box 9-3). Clinical evidence of rheumatoid pleurisy appears in about 20% of patients, but only 5% have radiologic evidence of effusions. In contrast, pleural involvement may be found in 50% of autopsy series. Pleural disease occurs much more frequently in men than in women with rheumatoid disease. Rheumatoid pleurisy usually occurs in the sixth decade of life and is associated with moderate to severe arthritis. Rheumatoid factor is present in the serum and the pleural fluid in high titers. The pleural fluid is exudative and characterized by a low glucose concentration and low pH.

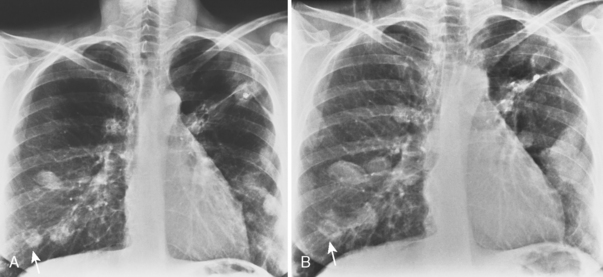

The chest radiograph usually shows a small- to medium-sized pleural effusion. It is typically unilateral, with a slight predominance on the right. Rheumatoid effusions tend to remain unchanged for many months or even years. Other manifestations of rheumatoid lung disease, such as interstitial fibrosis, are usually absent. The effusions may be recurrent and occasionally result in a diffusely thickened pleura or fibrothorax (Fig. 9-2).

Interstitial Fibrosis and Pneumonitis

Interstitial lung disease (Box 9-4) may be seen in a variety of collagen vascular diseases. Histopathologically, the abnormalities may take the form of any of the various idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, including usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP), nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP), cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP). Whereas NSIP is the most common histopathologic pattern in most collagen vascular disorders, UIP predominates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The prevalence may be as high as 30%. Immunologically mediated injury most likely plays a central role in this interstitial pneumonitis, and immune complexes (i.e., type III reaction) containing rheumatoid factor have been identified in alveolar walls and pulmonary capillaries by immunofluorescence.

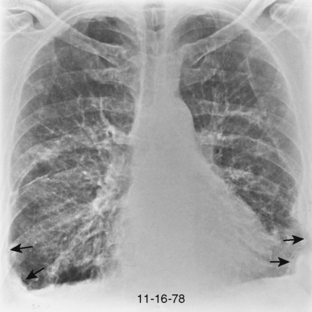

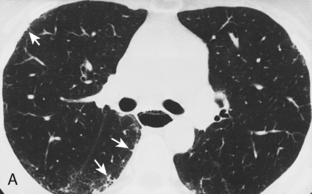

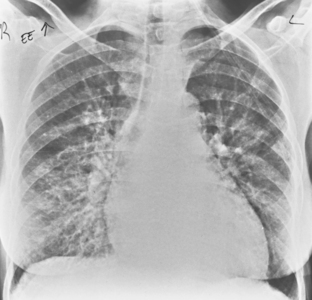

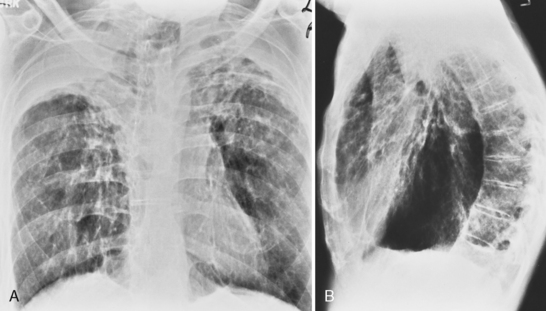

The radiologic features of rheumatoid interstitial disease are usually identical to those seen in UIP (Fig. 9-3) and NSIP. In the early stages, a pattern of fine linear or irregular opacities can be identified predominantly in the bases, which may progress to coarse reticulation with end-stage cystic changes and honeycombing. CT findings include reticular opacities located predominantly in the subpleural regions in the lung bases; ground-glass attenuation (especially in NSIP) (Fig. 9-4); irregular pleural and mediastinal interfaces; thickened interlobular septa; and honeycomb cysts (especially in UIP). Progressive loss of volume (“shrinking lungs”) may be observed on serial studies. Pleural effusion or thickening may be present. Occasionally, other features of rheumatoid disease may be observed in the bony thorax, including typical arthritic changes in the shoulder, joints, and tapering of the distal clavicles.

Necrobiotic Nodules

Radiographically, these lesions appear as multiple, well-circumscribed pulmonary nodules that are usually located in the periphery of the lungs (Fig. 9-5). Cavitation is common, and the walls are usually thick and smooth. Changes in the size of nodules may be observed; these correlate with the activity and treatment status of the disease. Although nodules usually cause no symptoms, they may rarely lead to complications, including pleural effusion, pneumothorax, bronchopleural fistula, hemoptysis, and infection.

Airways Disease

Bronchiectasis has been reported in up to 30% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In most cases, it is not clinically significant. Obliterative bronchiolitis may be caused by rheumatoid arthritis or several drugs used to treat this condition, including d-penicillamine, gold, and sulfasalazine. This disorder is discussed separately in Chapter 13. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may also develop follicular bronchiolitis, a benign condition characterized by lymphoid hyperplasia of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT). This entity is discussed separately at the end of this chapter.

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis: Scleroderma

Characteristics

Progressive systemic sclerosis or scleroderma (Box 9-5) is a connective tissue disease characterized by fibrosis and atrophy of the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, heart, and kidneys. Patients are usually affected in the fourth to sixth decade of life, and the disease is three times more common in women than in men.

Radiographic Features

The radiographic pattern is usually identical to that seen in NSIP or UIP and may be indistinguishable from rheumatoid lung. NSIP is the most common histopathologic pattern in patients with systemic sclerosis. A fine linear pattern of small, irregular opacities can be identified, with predominant involvement at the bases and often accompanied by ground-glass attenuation. As the disease progresses, the opacities become coarser, and eventually, traction bronchiectasis and honeycomb cysts develop. The latter pattern is a typical feature of UIP. Progressive loss of volume occurs over several years. Pleural involvement, however, is uncommon. On high-resolution CT (Fig. 9-6), findings are similar to those described in rheumatoid lung disease. In patients with systemic sclerosis, interstitial lung disease is frequently accompanied by thoracic lymphadenopathy, which tends to increase as the profusion of lung disease worsens.

Other nonpulmonary manifestations of scleroderma may be identified on the chest radiograph. Calcinosis may be present in the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the thorax, particularly about the shoulders. Atrophy and atony of the esophagus that results in absent peristalsis may also lead to dilation of the esophagus. On chest radiography and CT, this is manifested by the presence of gas without an air-fluid level in a distended esophagus, the so-called air esophagram (see Fig. 9-6). Dilation of the central pulmonary arteries with rapid tapering of peripheral vessels is characteristic of pulmonary arterial hypertension (Fig. 9-7).

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The clinical manifestations of pleural pulmonary lupus vary. Symptoms include pleuritis and cough with or without dyspnea. Pleuritis occurs in 35% to 40% of patients and is often painful and accompanied by fever. Patients occasionally have hemoptysis associated with pulmonary hemorrhage. The radiographic manifestations may be classified in six categories (Box 9-6), and patient may have more than one of these entities.

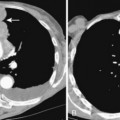

Pleuritis and/or Effusion

Separately or combined, pleuritis and effusion are the most common pleuropulmonary abnormalities in SLE. Pleuritis is often an early manifestation of disease and may have exacerbations. The effusions are commonly bilateral and small, although they may be massive. Pericardial effusions may also be present (Fig. 9-8). The fluid is an exudate with a high protein content and normal glucose concentration.

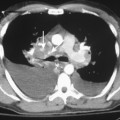

Acute Lupus Pneumonitis

Acute lupus pneumonitis is an uncommon but well-recognized manifestation of SLE. It is characterized by severe dyspnea, nonproductive cough, fever, and hypoxia. The radiographic features (Fig. 9-9) consist of poorly defined focal areas of increased opacity at the bases or widespread, extensive, unilateral or bilateral consolidation. These pulmonary opacities usually respond to steroids or cytotoxic drugs. The pathogenesis of this disorder is unclear, but histologic alterations include vasculitis and hemorrhage.

Polymyositis or Dermatomyositis

Characteristics

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (Box 9-7) include a group of autoimmune disorders characterized by diffuse inflammatory and degenerative changes in striated muscle. Fewer cases are associated with underlying malignancy. Symptoms include dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough. There is evidence of restriction on pulmonary function testing, and there may be a profound weakness of the muscles of respiration. The cause is unknown, and unlike other collagen vascular diseases, there are no circulating immune complexes.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Involvement of the thoracic spine is common in ankylosing spondylitis. Between 1% and 2% of patients also may develop pleuropulmonary manifestations, most commonly in the form of upper lobe fibrotic and bullous disease (Fig. 9-10). Although it is rare, ankylosing spondylitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic infiltrative lung disorders that cause upper lobe scarring and fibrosis.

VASCULITIDES AND GRANULOMATOSES

Characteristics

Any disease characterized pathologically by an inflammatory response within blood vessels may be considered a vasculitis. If the inflammation produces destruction of vessel walls, the process is called a necrotizing vasculitis. Most vascular diseases are systemic, although there often is a target organ. The lungs commonly are involved by several types of vasculitis. Box 9-8 provides a classification that divides these disorders into four groups. This section deals with diseases in category 1, those that histopathologically have a granulomatous appearance and have been characterized by Liebow as pulmonary angiitis and granulomatosis. In all these diseases, the lung is the major site of involvement. These granulomatous vasculitides include classic and limited Wegener’s granulomatosis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, allergic granulomatosis (i.e., Churg-Strauss syndrome), necrotizing sarcoid angiitis and granulomatosis, and bronchocentric granulomatosis.

Wegener’s Granulomatosis

Characteristics

Wegener’s granulomatosis (Box 9-9) usually consists of a disease triad of necrotizing vasculitis that involves the upper respiratory tract, lungs, and glomeruli of the kidneys. However, the limited form of Wegener’s is confined to the lungs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree