Diseases of the Airways

Jannette Collins

J. Collins: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

TRACHEA

Normal Anatomy

The extrathoracic trachea is 2 to 4 cm in length and extends from the lower border of the cricoid cartilage to the thoracic inlet. The intrathoracic trachea is 6 to 9 cm in length and extends from the thoracic inlet to the carina.45 Tracheal shape is variable, depending on the phase of the respiratory cycle. The shape of the intrathoracic trachea is round or elliptical on inspiration images and horseshoe-shaped during and at the end of a forced expiration, owing to anterior bowing of the posterior, noncartilaginous tracheal membrane.147 Normal coronal and sagittal tracheal dimensions as determined by chest radiographs are, respectively, 25 mm and 27 mm for men and 21 mm and 23 mm for women. The lower limit of normal for both dimensions is 13 mm in men and 10 mm in women.14 Normal tracheal dimensions in children, determined both radiographically and with computed tomographic (CT) scanning, have also been reported.32,57,90 Chest radiographs exposed at full inspiration and at maximal expiration show only minimal differences in the coronal and sagittal dimensions of the trachea, whereas CT scanning can show dramatic changes in caliber. Mean CT anteroposterior and transverse diameters of the extrathoracic trachea, respectively, are 20.1 mm and 18.4 mm15; these can increase by as much as 15% in men with aging.49 Stern and coworkers147 showed, from a dynamic CT study of young men, that tracheal cross-sectional area differs an average of 35% from end-inspiration to end-expiration, with a range of 11% to 61%.

CT scanning is superior to chest radiography in allowing detection of abnormalities of the major airways. The sensitivities for detecting disease are 66% and 97% for chest radiographs and CT, respectively.76 Although routine CT scanning can be extremely accurate in detecting focal endobronchial lesions, it is inaccurate in predicting whether a given abnormality is endobronchial, submucosal, or extrinsic (peribronchial).106 Spiral CT, which allows for the acquisition of a whole thoracic volume during a single breathhold, thereby eliminating respiratory motion, is the technique of choice for noninvasive imaging of the airways. Volume acquisition has fostered a renewed interest in two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions applied to the tracheobronchial tree. Multiplanar 2D images are additive to transaxial CT, allowing for better definition of the longitudinal extent of abnormalities involving the central airways.77,79,93 Potential clinical applications of 3D reconstructions include assisting with diagnoses, replacing bronchoscopy, and helping in surgical planning and endobronchial treatments.36 In one study, 3D helical CT accurately assessed 36 of 36 central stenoses that were seen on bronchoscopy, but missed 2 of 3 segmental stenoses seen on bronchoscopy; 18 stenoses could not be passed with a bronchoscope, but 3D helical CT provided details for possible endobronchial procedures (length of stenosis, patency, and spatial orientation of distal bronchi).68 More recently, virtual bronchoscopy simulations that use the volume-rendering technique have been introduced.164 Virtual bronchoscopy’s inability to render subtle mucosal detail or obtain diagnostic specimens does not obviate the need for conventional bronchoscopy, but virtual bronchoscopy may have a role in prebronchoscopy planning (choosing bronchial endoprostheses and planning laser treatments for stenoses), endoscopy training, and/or endobronchial therapy (calculating tumor volumes before brachytherapy).36,164

Tracheal Disorders Causing Tracheal Widening or Narrowing

A number of diseases can affect the trachea. Patients may be asymptomatic, or they may present with cough, dyspnea, wheezing, and stridor. The misdiagnosis of asthma is common.75 Tracheal disorders are generally organized into those that cause tracheal widening and those causing narrowing.

CT scanning can demonstrate the degree of widening or narrowing in addition to the location and extent of tracheal abnormality and the presence of associated mediastinal disease, postobstructive atelectasis, and pneumonitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appears to be an ideal method for imaging the trachea because of its multiplanar demonstration of the airway, mediastinal vessels, and other structures simultaneously without the need for contrast media. MRI is particularly useful in patients with either vascular rings or tracheal compression by the innominate artery. The present resolution of MRI, however, does not permit detailed evaluation of the bronchial tree, which is better performed with CT.46

CT scanning can demonstrate the degree of widening or narrowing in addition to the location and extent of tracheal abnormality and the presence of associated mediastinal disease, postobstructive atelectasis, and pneumonitis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appears to be an ideal method for imaging the trachea because of its multiplanar demonstration of the airway, mediastinal vessels, and other structures simultaneously without the need for contrast media. MRI is particularly useful in patients with either vascular rings or tracheal compression by the innominate artery. The present resolution of MRI, however, does not permit detailed evaluation of the bronchial tree, which is better performed with CT.46

Disorders Causing Tracheal Widening

Nonacquired diffuse tracheal widening is much less common than tracheal narrowing and has a more limited differential diagnosis. The Mounier-Kuhn syndrome, primarily affecting men in the fourth and fifth decades, accounts for almost all cases of nonacquired tracheal widening.19 Mounier-Kuhn syndrome, thought to be congenital but possibly acquired,9 is an abnormality of the trachea and main bronchi characterized by atrophy or absence of elastic fibers and thinning of muscle, which allows the trachea and main bronchi to become flaccid and markedly dilated on inspiration, with narrowing or collapse on expiration or cough. The abnormal airway dynamics and pooling of secretions in broad outpouchings (diverticula) of redundant musculomembranous tissue between the cartilaginous rings predispose to the development of chronic pulmonary suppuration, bronchiectasis, emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis.174 Patients may be asymptomatic, have minimal disease with good preservation of pulmonary function, or have progressive disease that leads to respiratory failure and death. The trachea is involved from the subglottic region to the carina, and although a tracheal diameter greater than 3 cm is required for diagnosis, tracheal widths up to 5.5 cm have been recorded.19 The radiographic features of the condition include marked dilatation of the trachea and main stem bronchi, tracheal diverticulosis, and a variable incidence of bronchiectasis and chronic pulmonary parenchymal disease. The CT scan features are similar.31,133 Many cases of this disorder probably go undiagnosed or are not recognized clinically or radiographically, but only on CT scanning.133 Roditi and coworkers126 studied 75 adults referred for CT assessment of possible bronchiectasis and a control group of 75 patients being staged for lymphoma and found that 7 (17%) of 42 patients with bronchiectasis had tracheomegaly and 2 of 33 patients without bronchiectasis had tracheomegaly on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). Tracheomegaly, therefore, may be a frequent finding in bronchiectasis. People with large tracheas, which may be overlooked unless tracheal dimensions are measured, may be at risk for development of bronchiectasis.

Several conditions can result in acquired tracheobronchomegaly that may closely resemble that seen in Mounier-Kuhn syndrome. Some degree of tracheal dilatation may be seen with aging38,49 and with certain occupations (musicians who play wind instruments, drill sergeants, and Moslem muezzins).38 Chronic infection, cigarette smoking, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, cystic fibrosis (CF), inhalation of noxious fumes, chronic intubation, and diffuse pulmonary fibrosis can also result in tracheobronchomegaly.13,173,174 Other conditions associated with tracheal widening, which may in fact be related to Mounier-Kuhn syndrome, are Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and cutis laxa.18,166 Finally, although tracheal narrowing is the usual end result in relapsing polychondritis, a disorder of cartilaginous inflammation involving the nose, ear, trachea, and joints, diffuse tracheal widening has occasionally developed.35 Nasal and ear cartilage abnormalities are absent in Mounier-Kuhn syndrome. Tracheobronchomalacia (Williams-Campbell syndrome), a disorder of cartilage deficiency, is an uncommon cause of tracheomegaly.

Disorders Causing Tracheal Narrowing

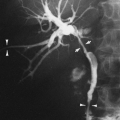

Tracheal narrowing is seen with saber-sheath deformity, amyloidosis, relapsing polychondritis, tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica, complete cartilage rings (“napkin ring” anomaly or congenital tracheal stenosis), scleroma, sarcoidosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, tracheobronchitis associated with ulcerative colitis, tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia, trauma (including postintubation stricture and surgical trauma), neoplasms, infectious disorders, extrinsic processes (vessels, nodes, thyroid and other mediastinal masses) (Fig. 26-1), and mediastinal fibrosis; it can also be idiopathic.5,75,131,149

Strictures of the trachea are usually caused by damage from a cuffed endotracheal or tracheostomy tube or trauma to the neck.47 Postintubation tracheal injuries remain the most common indication for tracheal resection and reconstruction, despite identification of the causes of these lesions and development of techniques for their avoidance.55 CT scans can demonstrate the site of narrowing in most cases, although a web or stenosis that involves a short segment may be missed because of volume averaging, and CT may overestimate the severity of a fixed stenotic segment and underestimate the length of the abnormal trachea.75 Quint and colleagues116 evaluated 27 patients who underwent lung transplantation and 17 nontransplantation patients with suspected airway abnormalities and found helical CT with multiplanar reconstructions to be more accurate than thin-section axial CT in the demonstration of mild stenosis, the length of a stenosis, and horizontal webs. Tracheomalacia, diagnosed when the trachea collapses more than 50% on expiration, can also result from trauma; it may be recognized only on expiratory CT scanning.116,147

Saber-sheath trachea is an intrathoracic narrowing of the trachea, with the coronal diameter equal to or less than two thirds of the sagittal diameter when measured 1.0 cm above

the top of the aortic arch.51 More than 95% of patients with this deformity have clinical evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and saber-sheath trachea is considered a valuable sensitive and specific sign for COPD on standard chest radiography.51,52 The CT diagnosis of saber-sheath trachea has been correlated with various functional, clinical, and radiographic signs of COPD.157

the top of the aortic arch.51 More than 95% of patients with this deformity have clinical evidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and saber-sheath trachea is considered a valuable sensitive and specific sign for COPD on standard chest radiography.51,52 The CT diagnosis of saber-sheath trachea has been correlated with various functional, clinical, and radiographic signs of COPD.157

Relapsing polychondritis is a systemic autoimmune connective tissue disease in which cartilage is affected diffusely by recurrent episodes of inflammation. The pinnal, nasal, laryngeal, and tracheal cartilages are most commonly involved. The major airways are involved in more than 50% of cases, and recurrent pneumonia is the most common cause of death in these patients.19,43 Collapsibility of the major airways is seen in conjunction with softening and destruction of the cartilaginous rings. On CT scanning, a fixed narrowing of the tracheobronchial lumen with associated thickening of the wall is seen.29,99 Dense calcium deposits may be seen in the thickened tracheal cartilage.65 Rarely, diffuse tracheal widening can result.

Amyloidosis of the respiratory tract, both primary and secondary, is a rare condition that produces irregular narrowing of the airway by submucosal deposits of amyloid in a focal or diffuse distribution.47 Both chest radiography and CT scanning may demonstrate diffuse narrowing or show nodular protrusions into the tracheal lumen that may show calcification.19 The average patient age is 53 years, and men are affected twice as frequently as women.19

Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica is a benign condition characterized by multiple submucosal osteocartilaginous growths along the inner anterolateral surfaces of the trachea.81,130 Men are more frequently affected than women (3:1), and the average age is more than 50 years (range, 11 to 78 years).19 Although the cause is unknown, theories have linked this disorder to chronic inflammation, degenerative processes, amyloidosis, and neoplasia.3,167,177 Chest radiography and CT scanning show multiple sessile nodular tumors, with or without calcification, extending over a long segment of the trachea. The nodules in amyloidosis may be circumferential, but those of tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica spare the posterior membranous wall.

Wegener’s granulomatosis is characterized by granulomatous vasculitis of the upper and lower respiratory tract, usually in conjunction with renal and other organ involvement. The CT appearance includes circumferential narrowing of the airway lumen, abnormal soft tissue within the tracheal rings, and dense irregular calcification of the tracheal cartilages.145 Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous disorder that may involve the trachea and bronchi. Granulomatous lesions may exist intrinsically in the airway, or enlarged hilar nodes may compress the bronchi extrinsically. CT scanning may show extrinsic compression by adenopathy and bronchial wall thickening.88,171

Ulcerative colitis has a rare association with bronchitis, bronchiectasis, and bronchiolitis.163 On CT scans, the tracheobronchial walls are thickened, producing irregular narrowing, and bronchiectasis may be seen.75 Finally, the major airways may be involved in viral, bacterial, fungal, or other infectious disease processes. In North America, most cases of laryngotracheobronchitis are viral in nature; subglottic or laryngeal narrowing is common, but radiographically demonstrable tracheal narrowing is unusual.75

Tracheal Filling Defects

In adults, tracheal filling defects are usually produced by neoplasms. Other causes include ectopic thyroid, infection, hematoma, amyloidosis, tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica, foreign body, mucus, and invasion from an extrinsic process. Reported airway lesions in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) include Kaposi’s sarcoma, tuberculosis, aspergillus, lymphoma, lung cancer, bacterial tracheobronchitis, bacillary angiomatosis, cytomegalovirus tracheitis, actinomycosis, Pneumocystis carinii tracheobronchitis, and granular cell myoblastoma.67

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) in adults is almost exclusively an acquired lesion, occurring as a complication of intrathoracic malignancies (accounting for 60% of cases), infection, or trauma.20,142 Diagnosis usually is made with a fluoroscopic contrast study, but it can be made in some cases by CT scanning. In addition to demonstrating the site of the fistula, CT scanning can suggest the cause and detect pulmonary and mediastinal complications.161 Because of its ease of performance in critically ill patients and its anatomic display, CT has been recommended as the diagnostic modality for TEF.161 Because of free ingress of air from the trachea to the esophagus, the precise location and size of the communication is outlined by air contrast on CT scanning. Small

fistulae may be intermittently blocked by food particles, inflammatory edema, and coagulated blood, and in these cases CT may not show the fistula.11

fistulae may be intermittently blocked by food particles, inflammatory edema, and coagulated blood, and in these cases CT may not show the fistula.11

Congenital Tracheobronchial Anomalies

Congenital tracheobronchial anomalies include absent or accessory bronchi (Fig. 26-2), tracheobronchial webs or stenosis, tracheobronchomalacia, short trachea, anomalous branching patterns, and association with and compression from anomalous pulmonary vasculature. Some of these represent life-threatening emergencies at birth, and others go undiagnosed for years. Clinical symptoms are often nonspecific, and radiographic evaluation is frequently required to localize and characterize the lesion before endoscopy, surgery, or medical management. The radiologist must be alert for unsuspected additional anomalies involving airway, lungs, and esophagus, which occur with relative frequency.

Tracheal webs produce localized narrowings with no associated deformity of the underlying cartilage. Web thickness determines the severity of obstruction and the therapeutic approach.17 Congenital tracheal stenosis can occur in any portion of the trachea; it usually involves more length and depth of the trachea than webs and is more likely to require resection rather than dilatation alone. Stenosis secondary to long-term compression by a dilated esophagus, abnormal great vessels, or cervicomediastinal masses results in a focal fibrous and cartilaginous deformity that persists for some time after the mass is removed. Congenital tracheal stenosis is frequently associated with bronchial stenosis; pulmonary hypoplasia or agenesis; tracheal bronchus; TEF; tracheomalacia; anomalies of vertebrae, ribs, and thumbs; and cardiac anomalies. Tracheomalacia is an abnormally flaccid trachea; it may involve all or part of the trachea and results in anteroposterior tracheal collapse during expiration. The innominate artery compression syndrome can result in secondary tracheomalacia where there is persistent narrowing of the anterior tracheal wall at the level of the thoracic inlet. Shorttrachea, resulting from the presence of 15 or fewer tracheal rings, can be diagnosed on CT scanning when the tracheal bifurcation lies above the fourth thoracic vertebral body in children younger than 2 years old or above the fifth thoracic vertebra in older children.168

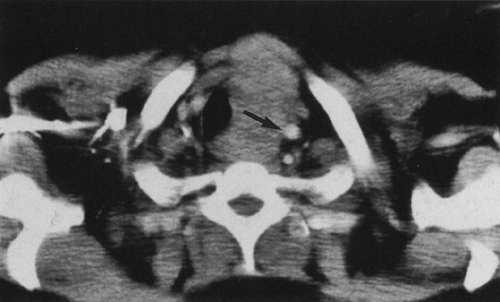

Aberrant tracheal bronchus (pig bronchus) is reported in 2% of children during bronchoscopic examination.87 It almost always occurs in males, most often arises from the right lateral tracheal wall within 2 cm of the carina, and may be asymptomatic or result in right-upper-lobe infection, atelectasis, or bronchiectasis, usually from a stenotic bronchial segment and poorly cleared secretions (Fig. 26-3). Two types are described. The supernumerary type is associated with a normal trifurcating right-upper-lobe bronchus. In the displaced type, the ectopic bronchus supplies the apical segment of the upper lobe. The CT appearance is that of a bronchus arising from the trachea in a section more cephalad than the carina and the presence of only two segmental bronchi arising from the anatomic right-upper-lobe bronchus when the anomaly is of the displaced type.135 Accessory cardiac bronchus arises from the medial wall of the intermediate bronchus.85 Bridging bronchus is an anomaly of the branching pattern of the tracheobronchial tree, with the middle and lower lobes of the right lung supplied by a bronchus that arises from the medial aspect of the left main bronchus and “bridges” the mediastinum in its course to the right lung.50 Radiologically, the bridging bronchus can be seen branching from the left main bronchus at a thoracic vertebral level (T5-T6) lower than that of the normal carina. Bridging bronchus may be associated with left pulmonary artery sling,169,170 in which case the left pulmonary artery runs over the bridging bronchus and behind the left main bronchus to

the left lung. The right main bronchus may supply the upper lobe of the right lung, or it may be absent or present only as a blind diverticulum of the airway at the carinal level.

the left lung. The right main bronchus may supply the upper lobe of the right lung, or it may be absent or present only as a blind diverticulum of the airway at the carinal level.

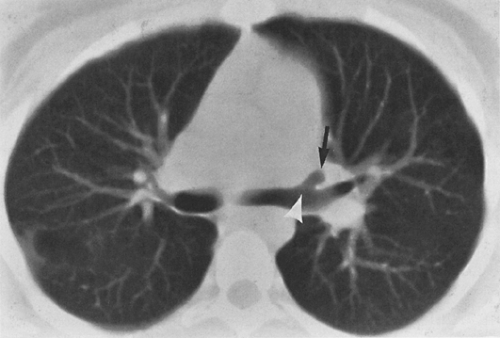

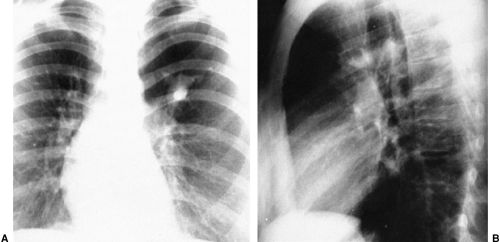

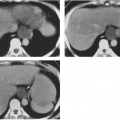

Congenital bronchial atresia detected initially in an adult is usually an incidental finding. The atresia most commonly occurs in the upper lobes of the lungs, especially the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe. Both chest radiography and CT scanning show mucus plugging (mucocele) in a branching pattern, with associated segmental hyperinflation117 (Fig. 26-4).

BRONCHI

Bronchial Anatomy

The trachea bifurcates, giving rise to the left and right main stem bronchi. In adults, the right main stem bronchus is more vertical, wider by about 2 mm, and approximately half the length of the left main stem bronchus.6 The right main stem bronchus ends at the lateral origin of the right-upper-lobe bronchus, and the main stem continues as the bronchus intermedius, which terminates where the middle-lobe bronchus originates anterolaterally and the superior segmental bronchus to the right-lower-lobe originates. The main airway continues as the lower-lobe bronchus, which divides into anterior, lateral, posterior, and medial basal segmental bronchi. Divisions on the left are similar except that there is a short left-upper-lobe bronchus, which bifurcates into the lingular bronchus and a short trunk that almost immediately divides into anterior and common apicoposterior segmental airways. After giving rise to the superior segmental bronchus to the left lower lobe, the lower-lobe airway continues inferiorly, dividing into three or four basilar segmental bronchi (in some instances there is a common anteromedial bronchus). The airways, to the subsegmental level, are visualized with CT scanning when 3- to 5-mm thin-section collimation is used. Woodring and associates174 determined the normal dimensions of the main bronchi from chest radiographs to be 13 to 20 mm on the right and 11 to 17 mm on the left for men, and 11 to 20 mm on the right and 8 to 17 mm on the left for women.

Bronchiectasis

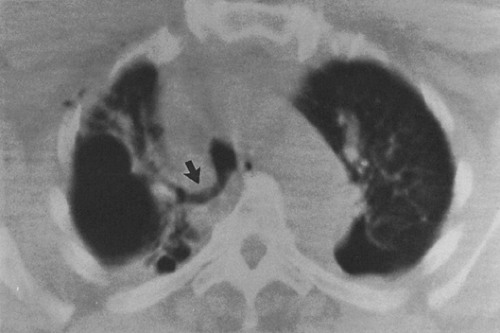

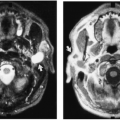

Bronchiectasis, defined as irreversible dilatation of the bronchial tree, may cause chronic sputum production and hemoptysis, or it may be asymptomatic. It can be described as cylindrical, varicose, or cystic in type.121 Cylindrical bronchiectasis, the mildest form, is characterized by smooth, uniformly dilated bronchi; sectioned lengthwise these bronchi resemble “tram tracks,” and sectioned crosswise they appear round or oval. Beaded dilatation of bronchi describes the varicose type (Fig. 26-5). Cystic bronchiectasis, the most severe type, is characterized by cysts in clusters, often with air–fluid levels (Figs. 26-6, 26-7). The theories of pathogenesis include obstruction, infection, and traction.23,24,34,40,41,78,84,94,111,125

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree