Common Flexor Origin Enthesopathy

Tendinopathy of the common flexor origin (CFO) is less common than its extensor counterpart. The presenting features are similar, although the sporting and occupational associations are different. There is a particular sporting association with golf and the term golfer’s elbow has come into common use. Other names, such as medial tennis elbow and flexor–pronator sprain, are also applied.

Flexor–pronator sprain is a useful term and it draws attention to the common association with injury to the pronator teres muscle, which overlies the CFO.

The ultrasound findings are similar to CEO tendinopathy. As has been previously discussed, the configuration of CFO is different from that on the extensor side.

| The musculotendinous junction is more proximal so the overall ultrasound appearance is of a more muscular or fleshy appearance compared with the CEO ( Fig. 7.1 ). |

| There is a close association between CFO tendinopathy and ulnar neuritis, and in many patients the symptoms overlap. |

This is because the floor of the cubital tunnel receives some fibres from the dorsal aspect of the CFO and consequently tendinopathy of the CFO may also irritate the overlying ulnar nerve. As symptoms may be difficult to differentiate on clinical grounds, an assessment of both of these structures should be carried out in patients presenting with medial elbow pain. The differential diagnosis also includes injuries to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL), median neuropathy and pronator teres.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament

Stability of the elbow joint depends on intact bony and ligamentous structures. Medial stability depends on soft tissue integrity throughout the majority of the flexion/extension range, as bony structures only provide stability at less than 20° and more than 120°. The medial collateral ligament complex is composed of three components, the most important of which is the anterior limb, which is generally referred to as the UCL. Anatomically the ligament arises on the under surface of the medial epicondyle as a fan shaped attachment and inserts onto the sublime tubercle of the ulna.

There has been considerable study of the biomechanics of throwing, particularly in North America where throwing sports play such an important role in late childhood and adolescence. The overhead throwing sequence is divided into a number of phases, with stress being placed on different structures in each phase. The phases are an initial wind-up, early and late cocking, early and late acceleration, deceleration and follow through. Poor technique tends to lead to increased valgus forces, which in turn lead to tension along the ulnar aspect of the elbow.

Knowledge of the point in the throwing cycle where symptoms occur gives a useful clue to the most likely injury.

If medial instability becomes chronic the sequelae include valgus extension overload, olecranon stress fractures, ulnar neuritis and ultimately ulnotrochlear arthritis.

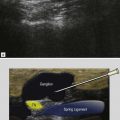

Injuries to the UCL include complete and partial rupture. Complete rupture is easier to diagnose than partial injuries. Complete rupture may be proximal or distal, and partial rupture tends to be distal and may be limited to separation of the joint surface of the ligament from the sublime tubercle of the ulna ( Figs 7.3, 7.4 and 7.5 ). Plain films are rarely helpful, although they can occasionally identify an enthesophyte. Ultrasound and MRI are both used, and MRI arthrography is superior to MRI for subtle injuries.

The ultrasound findings in UCL tear include disorganization of the normal fibrillary structure, increased size and laxity. In the acute phase free fluid may be seen to traverse the tear and exude from the joint into the surrounding soft tissues. Partial tears are more difficult to detect but in addition to disorganization of the ligament on ultrasound, focal pain is an important aspect of diagnosis.

| Strain of the UCL may only manifest as ligament dysfunction and stressing the ligament is important to detect these more subtle injuries. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree