Chapter Outline

COLLATERAL LIGAMENTS AND VOLAR PLATE

Introduction

This section will be divided into abnormalities that occur on the flexor side and those that occur on the extensor side of the fingers. Each section will deal separately with disorders of tendons and ligaments and retinacula. The flexor and extensor tendons of the hand are divided into zones to help describe and plan the treatment of injuries. The extensor zones are numbered 1 to 7, with the odd numbers overlying joints, beginning distally. Zone 1 is therefore the area overlying the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ) and zone 7 is overlying the wrist. The even-numbered zones lie between the joints. On the flexor side, there are 5 zones, also numbered from distal to proximal.

Flexor Tendons

Anatomy and Clinical Aspects

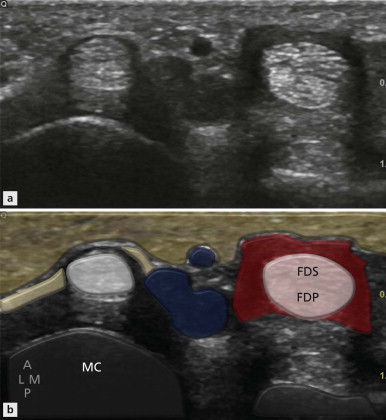

There are two flexor tendons to each finger: one superficial and one deep. Each arises from the corresponding flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor digitorum profundus muscle belly.

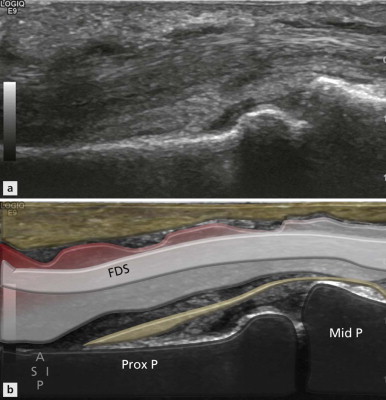

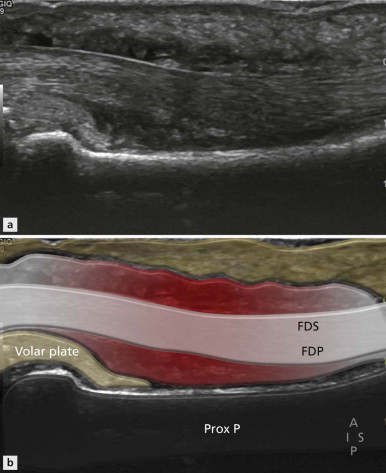

The superficialis tendon is the superior of the two finger tendons but it inserts first at the base of the middle phalanx. In order to achieve this, the tendon splits and sends a medial and lateral slip one each side of the profundus tendon to their respective insertions in the proximal part of the middle phalanx.

Disorders of the tendon and tendon sheath, as with tendons elsewhere, include tenosynovitis, tendinosis and tendon rupture. Tenosynovitis refers to inflammation on the tendon sheath. The term tendinosis is sometimes used for intratendinous mucinous degeneration, which is not associated with symptoms. Tendinopathy is a similar term, but in the same context indicates that symptoms are present. Others use the term tendinosis regardless of whether symptoms are present or not.

Tenosynovitis

A synovial sheath surrounds the two flexor tendons in the finger. These are separate from the tendon sheath surrounding the flexor tendons within the carpal tunnel.

| Patients with tenosynovitis may initially complain of stiffness and inability to form a fist and not infrequently arthritis is suspected. |

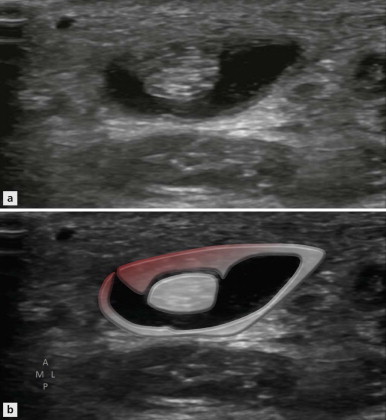

| The earliest ultrasound finding is the appearance of the dark halo around the tendon. |

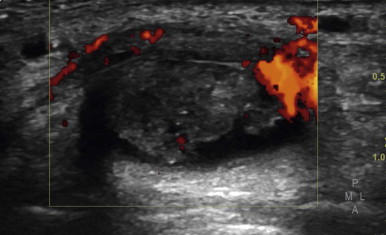

As the amount of fluid increases, the tendon sheath becomes increasingly distended ( Fig. 15.2 ). In long axis fluid and synovial thickening will not be evenly distributed along the length of the tendon ( Fig. 15.3 ), but will be initially constrained in the areas of the flexor pulleys, creating a lobulated appearance. This should not be misinterpreted as multiple ganglia. As the disease progresses, the degree of synovial thickening ( Fig. 15.4 ) and Doppler activity increases ( Fig. 15.5 ). At this stage associated tendinopathy is common and vascular ingrowth is identified within the substance of the tendon itself, alongside accompanying intratendinous matrix changes.

Tendon Rupture

Rupture of the flexor tendon may affect either the superficial or profundus tendon, although the latter is more common.

The commonest site of flexor profundus tear is just proximal to its insertion into the base of the distal phalanx.

Clinically there is localized tenderness, pain and swelling and inability to flex the DIPJ. The latter can be assessed during the ultrasound by fixing the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ). Additionally, during finger flexion there will be dysynchronous movement between the proximal and distal portions of the ruptured profundus tendon. Gentle finger movements are also helpful to distinguish between partial and complete tears. Synchronous movement between proximal and distal components of a suspected tear excludes a complete rupture in the acute phase.

| The flexor tendons are less strongly attached to the surrounding structures and thus the degree of retraction is often quite large. |

The location of flexor tendon rupture can also be reported using the zones method. Zone 1 covers the segment between the superficialis and the profundus insertions. Zone 2 is the area between the superficialis insertion and the distal palmar crease. In this segment the profundus and superficialis tendon lie in close proximity. Zone 3 is between the level of the A1 pulley and the flexor retinaculum. Zone 4 covers the section of flexor tendon within the flexor retinaculum and zone 5 that portion proximal to it. Jersey finger has its own classification as there is often a small bony avulsion fragment attached to the tendon which influences the degree of retraction encountered. If a large bony injury is involved, retraction proximal to the A4 pulley is uncommon. This is designated a type 3 lesion. In the rare type 4 lesion the profundus tendon may itself be avulsed from the avulsed bony fragment. Retraction of the tendon into the palm is designated a type 1 and retraction to the level of the PIPJ a type 2, completing the spectrum of lesions.

As it is required to cross fewer joints than its deeper counterpart, closed rupture of the superficialis tendon is uncommon but can occur due to forced extension against a contracted muscle. It is also less prone to abrasion against the carpal bones. Open tendon lacerations are a more common cause of superficial flexor tendon rupture and most frequently involve the midsubstance of the tendon.

Flexor Pulleys

Anatomy

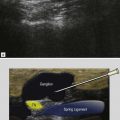

The flexor tendons of the hand are held in place by a series of connective tissue retinacula that are formed by condensations of the fibrous sheath. They are arranged into annular and cruciate configuration, referred to as the A and C pulleys ( Fig. 15.7 ). The pulley system is important for keeping the flexor tendons close to the phalanges to maximize their ability to flex the fingers. Clinically, the annular A pulleys are by far the most important and these are numbered A1–5. The A1, A3 and A5 are at the level of the metacarpalphalangeal, PIP and DIP joints respectively. They are on the convexities of the flexor tendons and are thus less prone to injury. The A2 pulley is at the level of the midportion of the proximal phalanx and the A4 pulley at the midportion of the middle phalanx ( Fig. 15.8 ). These are on the concavity of the flexor tendon and are more prone to injury.

The A2 is the largest of the pulleys. It can be visualized directly on ultrasound and note is made of any associated injury. Functionally, it is tested by noting the distance between the profundus tendon and the underlying bone when the finger is flexed against resistance. With a functioning pulley, the flexor tendon should show minimal separation from the underlying bone.

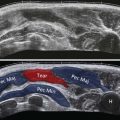

Pulley Injury

The classic injury leading to pulley rupture is typified by the crimp grip of rock climbers. Hyperextension occurs at the metacarpalphalangeal joint and flexion at the IPJ. If the weight supported by the fingers in this position is suddenly increased beyond the restraining ability of the pulley system, rupture occurs. The flexor tendons are pulled away from the phalanges and shorten. This is called bowstringing. The middle and ring fingers are the most vulnerable. There is some disagreement as to which pulley ruptures first, although most commonly the injury is said to begin at the distal portion of the A2 pulley. It then progresses through A4 with progressive bowstringing of the flexor tendon ( Fig. 15.9 ).

The degree of bowstringing measured by the separation of the flexor tendon from the underlying bone gives a clue on which pulleys are involved.

Ultrasound Imaging of Pulley Rupture

Injury to the pulley itself may be visualized by both ultrasound and MRI ( Fig. 15.10 ). Ultrasound offers an advantage over MRI in that the pulley can be stressed dynamically. The patient places the back of their hand on the examination couch and the probe is placed in long axis overlying the A2 pulley. A free finger of the examiner’s hand is placed on the distal phalanx of the finger being examined, restraining it as the patient flexes ( Fig. 15.11 ). Under normal circumstances, the tendon is constrained by an intact pulley system and there is a minimal gap between the profundus tendon and the underlying bone.

| If the A2 pulley has ruptured, the tendons will lift from the proximal pahalanx, creating a gap. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree