Chapter Outline

Introduction

The hip region is an area of complex anatomy with numerous vascular, nervous and muscular structures passing between the trunk and the lower extremity. Conditions remote to the hip joint may present as pain in the groin. Clinical examination may be nonspecific, and the choice of imaging modality may be difficult. Ultrasound is often used as a complementary technique to radiography, MRI and CT. Ultrasound-guided hip joint aspiration and injections are frequently utilized as an adjunct to diagnosis of hip and groin pain.

Common pathological processes that may be amenable to ultrasound evaluation include:

- •

Intraarticular hip pathology:

- •

effusions and synovitis

- •

labral tears.

- •

- •

Extraarticular soft tissue pathology:

- •

lymphadenopathy

- •

hernias

- •

bursitis

- •

tendon and muscle injury

- •

soft tissue masses.

- •

- •

Compression neuropathy.

- •

Complications of hip prostheses.

Intraarticular Hip Pathology

Joint Effusion

Hip joint effusion is difficult to diagnose clinically and plain radiographs are insensitive. Ultrasound can detect effusions as small as 1 mL of joint fluid.

Internal echoes may be seen within an exudative effusion, and there may be associated thickening of the joint capsule. However, the absence of internal echoes does not exclude infection, and ultrasound-guided aspiration is indicated to avoid delay in diagnosis. Ultrasound-guided hip aspiration or injection in adults is performed in the transverse plane with the probe over the femoral head or neck and a 22 G spinal needle introduced from a lateral approach. This enables the operator to keep the needle parallel to the probe face for optimal visualization.

Conversely, a negative ultrasound examination reliably excludes joint effusion and septic arthritis, and may be used to avoid unnecessary arthrocentesis. Osteomyelitis, however, is not excluded.

Synovitis

In inflammatory arthritis, synovial hypertrophy and hyperaemia occurs with distension of the joint capsule anteriorly. Simple effusions may also be present. Differentiating fluid from synovitis by evaluation of the echogenicity of fluid is unreliable, and the use of sonopalpation to displace fluid is less reliable than in small joints. Synovitis is not always associated with hyperaemia on Doppler imaging.

Marginal erosions may be detected in the periphery of the femoral head before they are visible on the plain radiographs. They appear as irregular cortical defects filled with hypoechoic, hypervascular pannus.

Proliferative Synovial Disorders

Synovial osteochondromatosis is a neoplastic condition of the synovial membrane. It presents with joint pain, recurrent swelling and intermittent locking. In the early stage of disease, there is hypertrophy of the synovium, with formation of chondral bodies that are released in the joint. In the final stage these bodies may calcify or even ossify. A thickened echogenic synovium may be demonstrated on ultrasound in the early stages, with areas of low echogenicity that represent chondral nodules that may not be visible on radiography. After mineralization, these nodules become echogenic and produce distal acoustic shadowing ( Fig. 18.2 ).

Other proliferative synovial disorders such as pigmented villonodular synovitis may be impossible to distinguish from simple synovitis, but should always be considered in patients with monoarthritis.

Acetabular Labrum

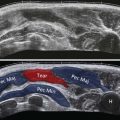

Labral tears most commonly occur in the anterosuperior labrum and this area is amenable to assessment by ultrasound. A labral detachment is identified by separation of the echobright fibrocartilagnous labrum from the acetabular rim by a hypoechoic line. Associated femoroacetabular impingement may be seen during internal rotation on a dynamic examination.

Labral tears are more apparent in the presence of paralabral cysts, which are analogous to meniscal cysts in the knee. Paralabral cysts are hypoechoic lobulated lesions and may have internal septations ( Fig. 18.3 ). They are generally noncompressible. Most cysts are small in size compared to the iliopsoas bursa and may have a thick wall. Uncommonly, large cysts may extend deep to the iliopsoas muscles and compress the femoral neurovascular bundle. These can rarely present as a groin mass.

Ultrasound demonstration of a labral tear or a cyst is often a fortuitous finding as part of a global examination of groin pain. When a labral tear and intraarticular pathology are suspected from clinical examination, MRI is the investigation of choice to evaluate the entire labrum, articular cartilage and other intraarticular structures.

Extraarticular Hip Pathology

Muscle and Tendon Disorders

Iliopsoas Tendon

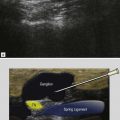

Iliopsoas tendon and paratendon abnormalities are increasingly recognized as a cause of groin pain, especially in athletes and dancers. Snapping hip and iliopsoas bursitis account for most cases of iliopsoas tendon abnormality. However, tendinopathy associated with osteophytes of the anterior acetabulum may be encountered with ultrasound, and tendon impingement may occur with large size hip prostheses.

Snapping Hip

Snapping hip syndrome is a condition in which there is an audible or perceptible click during the hip movement, and may or may not be associated with pain. Snapping hip may be due to intra- or extraarticular causes. Intraarticular snapping hip is due to labral tears or intraarticular loose bodies. Extraarticular tendon snapping is divided into medial and lateral types. The lateral type is due to iliotibial band or gluteus maximus snapping over the greater trochanter, and is discussed in Chapter 19 .

The medial type is due to abnormal movement of the iliopsoas tendon. It is now recognized that the snapping occurs more commonly due to abnormal rotation of the psoas tendon around the iliacus rather than snapping over the iliopectineal eminence.

| Dynamic ultrasound is performed in an oblique transverse plane along the line of the superior pubic ramus, with the patient in a supine position. |

| Alternatively, it is possible to dynamically assess the tendon as the hip is moved from a flexed, abducted and externally rotated position (frog lateral) to neutral. |

In cases refractory to analgesics and physiotherapy, ultrasound-guided injection of steroid and local anaesthetic into the iliopsoas bursa may be beneficial. If the bursa is not distended, the needle is introduced from a lateral position in the transverse plane posterior to the iliopsoas tendon and anterior to the acetabular rim.

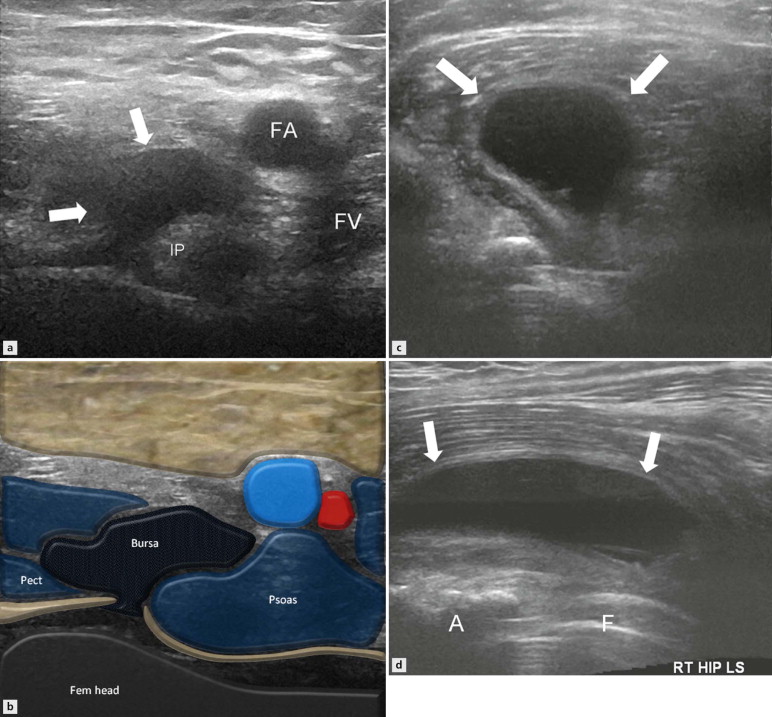

Iliopsoas Bursa

Iliopsoas bursitis usually presents as hip and groin pain, which may be exacerbated by hip flexion. Rarely a very distended bursa may present as a nonspecific mass in the groin. The bursa is situated deep to the musculotendinous junction of the psoas muscle, and communicates with the hip joint in 15% of patients. It is only visualized on imaging when it is distended with fluid ( Fig. 18.4 ). A fluid-filled bursa appears as a thin-walled cystic structure located between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and the iliopsoas tendon laterally. Bursal distension can rarely produce compression neuropathy of the femoral nerve. Large bursae may also extend into the pelvis along the iliacus muscle and may displace the pelvis structures.

Iliopsoas bursitis may also occur in association with several joint disorders such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, trauma and septic arthritis. In these cases synovial thickening, pannus and loose bodies may also be seen in the bursa. Very large bursae may also be seen in association with tuberculosis, in which case it is necessary to document the full intraabdominal extension.

Sartorius and Quadriceps

Sartorius and rectus femoris tendon injuries are an important cause of acute anterior hip pain and acute apophyseal avulsions may be encountered in skeletally immature patients ( Fig. 18.5 ). This type of injury is more common in kicking sports when the leg is hyperextended with hyperflexion of knee, leading to eccentric muscle loading. Large bone avulsion fragments are readily diagnosed on plain radiographs. Avulsions through the tendon fibrocartilage at the tendon insertion, with small or absent bone flakes, may not be visualized on plain radiographs. Sonography is useful in these cases as it can show continuity of tendon fibres with the fibrocartilage and bony avulsion fragments. In a full-thickness tear, there is tendon retraction and the gap is filled with haematoma. The extent of tendon retraction dictates the need for surgical intervention. In chronic cases calcification or ossification may develop in the injured muscle.