Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a disorder where under development of the acetabulum leads to reduced femoral head coverage which, in turn, predisposes to acetabular labral abnormalities and early cartilage disease. If uncorrected, these abnormalities predispose to premature osteoarthritis, requiring hip replacement. If dysplasia is severe, the femoral head may sublux or frankly dislocate. The older name for this condition, congenital dislocation of the hip, is now seldom used, largely because many patients may demonstrate acetabular dysplasia without frank dislocation at birth. Femoral head coverage and acetabular dysplasia are related, in that it is generally felt that a concentrically reduced femoral head can encourage development in a dysplastic acetabulum.

Background: Dysplasia vs Instability

Infants with more severe dysplasia are easier to detect clinically as the hip is either dislocated or can be made to dislocate on clinical examination. The classical Ortolani and Barlow manoeuvres look for a clunk as a dislocated hip is reduced or a click as a reduced hip becomes dislocated. In the past, many patients presented late in childhood and adolescence with a painful limp secondary to established osteoarthritis. The reason for this was that a child with a dysplastic acetabulum, but stable hip joint, will be normal on clinical examination, at least initially. Yet they also need active management to optimize femoral head containment and even distribution of weight-bearing force across the joint, in order to prevent cartilage damage.

In essence, clinical examination detects unstable but not stable dysplastic hips. The role of imaging is to identify all patients with dysplasia and prevent early cartilage degeneration.

Epidemiology

There is variation in the distribution of DDH worldwide. The reported incidence depends on the criteria used but is between 3 % and 10 % live births. It is significantly more common in girls, with a ratio of 9 :1, and there is an association with other congenital anomalies, such as talipes or neuromuscular disorders. The condition runs in families and there is a higher incidence in babies born in a breech position, where it has been argued that the hip anomaly underlies an inability for the baby to correct their position during late pregnancy. It is also more common on the left side than on the right.

Role of Ultrasound

Plain radiographs are poor at assessing acetabular dysplasia and hip subluxation. Some measurements, notably the acetabular angle, when combined with careful radiographic technique have some value, but difficulties with image reproduction and interobserver variation are still a problem. CT and MRI can be effective but the radiation or financial cost of these investigations precludes their use as a screening tool, especially in infants. Ultrasound is ideally placed to assess the infant hip as it can visualize the unossified components of the acetabulum and femoral head, is dynamic enough to assess subluxation and does not carry a radiation risk.

Ultrasound is used to assess both the depth of the acetabulum and joint stability. The former can be assessed either by measuring certain defined angles around the acetabulum, or by determining the proportion of the unossified femoral head which is contained within the acetabulum. Both of these assessments are carried out on a static standardized coronal ultrasound image of the hip. Ultrasound can also detect when the femoral head is either dislocated at rest or the ease at which it can be made to sublux by lateral pressure to the femoral head. A complete neonatal ultrasound hip examination, therefore, has both static and dynamic components. These allow the range of abnormalities to be detected and classified, so that appropriate treatment can be instigated.

Acquiring a Standard Image

In our institution, the child is examined in the decubitus position, though others advocate an anterior approach.

| The child is placed in a foam-filled trough to provide support and prevent excessive movement. |

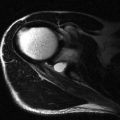

The key components of the image are the unossified femoral head and acetabulum ( Fig. 20.2 ). The ideal image should demonstrate the acetabulum at its maximal depth through the triradiate cartilage without excessive probe tilt. The reflective lateral wall of the ilium should be a straight line, parallel to the probe. A line drawn along this is called the base line. A sharp margin between the base line and the bony roof of the acetabulum should be present as the roof line turns downwards. Between the roof line and the femoral head lies unossified roof acetabular cartilage onto which the reflective fibrocartilaginous labrum attaches. Most of the femoral head is unossified. An ossified nucleus at various stages of development may be seen within it. Unossified femoral head cartilage has a typical speckled appearance. The speckles represent vessels and in some cases Doppler activity can be detected within them. The overlying hyaline cartilage representing articular cartilage has a smoother low-reflective appearance.

Graf Angles vs Coverage Measurements

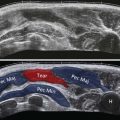

Graf is an orthopaedic surgeon who pioneered much of the early work in ultrasound assessment of the dysplastic hip. He describes two angles, α and β, which help define acetabular depth and femoral head coverage. The α angle is the angle between the base line and the acetabular ‘roof’ line ( Fig. 20.3 ). The β angle is the angle between the base line and a line drawn from the tip of the acetabular rim (junction of the base line and roof line) through the tip of the acetabular labrum. The two angles are used to classify the infant hip into specific types and this classification is used to determine management. The higher the α angle, the deeper the acetabulum.

The Graf classification uses four types. Type I is a normal hip anatomically, with an α angle of ≥ 60° and β ≤ 55°. A normal α angle but increased β angle, of more than 55, is classified as immature and designated Ib. A type II hip has α > 50°. Type IIb is used if the child is also older than 3 months and IIc if the α is less than 50° but more than 43°. Type III has α less than 43° and type IV when the hip is also dislocated.

An alternative method of assessing acetabular depth is to determine what proportion of the femoral head is contained within the acetabulum. If a line drawn along the base line is continued, it normally passes through the femoral head. The proportion of the femoral head diameter that lies below this line is measured ( Fig. 20.4 ) and the normal value is > 40%.

It will be noted from these two measurements that there is a relationship between the Graf α angle and femoral head coverage and both are used separately and together in different centres. The bigger the α angle, the steeper is the acetabular roof and the more femoral head will be contained by it. Conversely, a shallow hip has a lower α angle ( Fig. 20.5 ) and less of the femoral head is covered by acetabulum ( Fig. 20.6 ).

Correlation between the α angle and femoral head cover is lost in babies with very immature hips where there is a large unossified cartilage anlage. In these infants the α angle will be low, suggesting a shallow acetabulum, but femoral head coverage may be normal. This is because much of the femoral head will be covered by unossified cartilage, but covered nonetheless. The α angle is low because it is measured from the bony and not cartilage acetabular roof. This situation needs to be viewed with some caution as there may be a greater deforming pressure on the cartilage anlage than usual. Once this immature cartilage ossifies, the α angle becomes normal.

In addition to the acetabular angle and femoral head cover measurements, the shape of the acetabular rim should also be noted. In most cases the angle between the baseline and roof line is sharp, but in some it can appear notched or blunted. It has been suggested that a persistently subluxing hip is the cause of this notch.

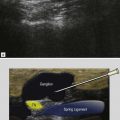

Dynamic Examination

Whatever method is used to assess acetabular morphology, the examination is incomplete without some evaluation of the dynamic stability of the joint. In the standard decubitus examination position of a right hip, the fingers of the operator’s right hand are extended along the inside of the infant’s thigh. Gentle abduction pressure can be applied by the examiners fingers and the relative position of the femoral head to the acetabulum noted during this manoeuvre. It is important not to apply counterpressure with the probe as this may prevent subluxation. Movement is best appreciated by observing the deep aspect of the femoral head and its relationship to the tri-radiate cartilage ( Fig. 20.7 ). More than 2 mm of subluxation is regarded as abnormal, though can be acceptable in premature infants. If laxity is detected, a repeat examination is recommended after 2 to 3 weeks to ensure that the hip is normalizing. Persistent subluxation needs to be actively managed.