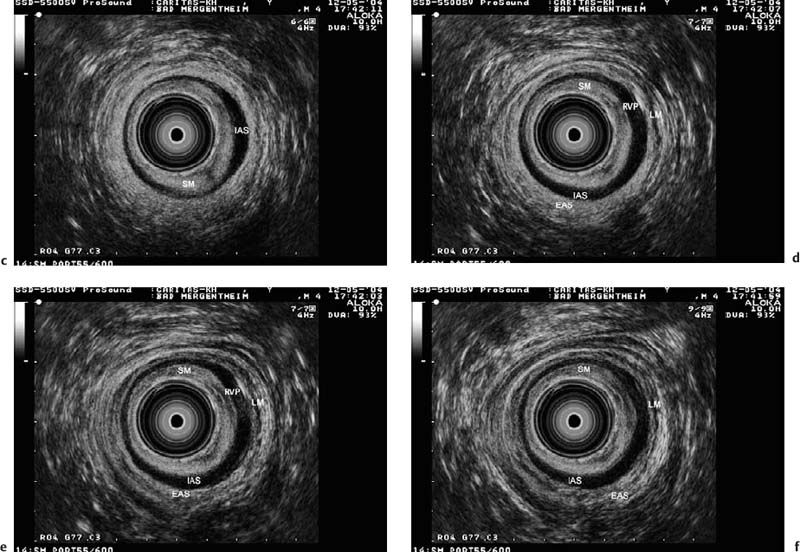

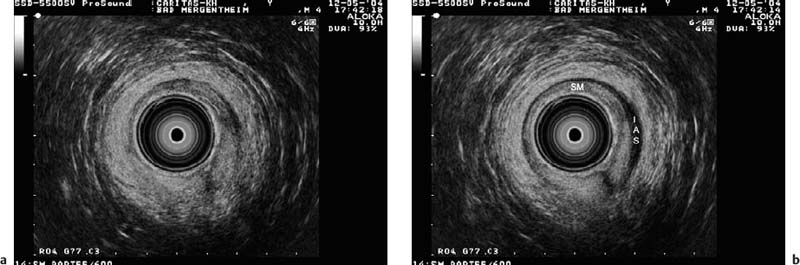

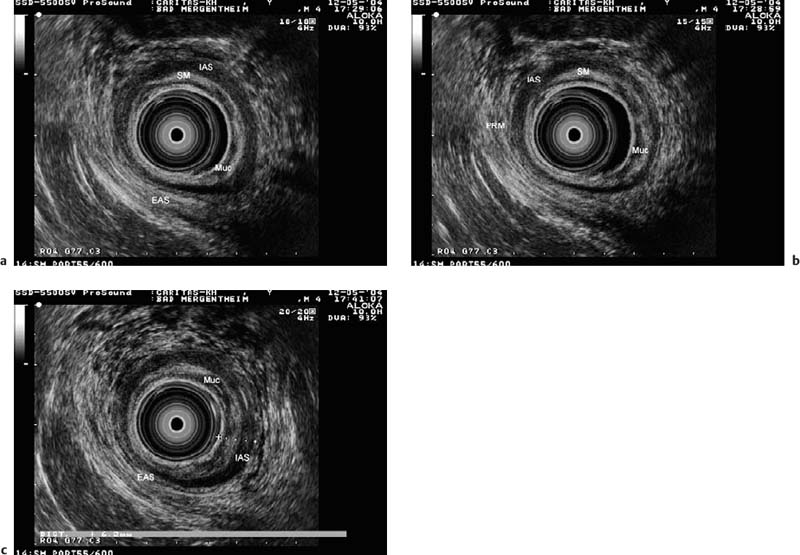

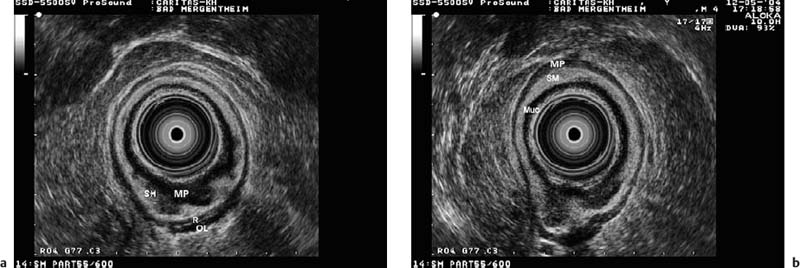

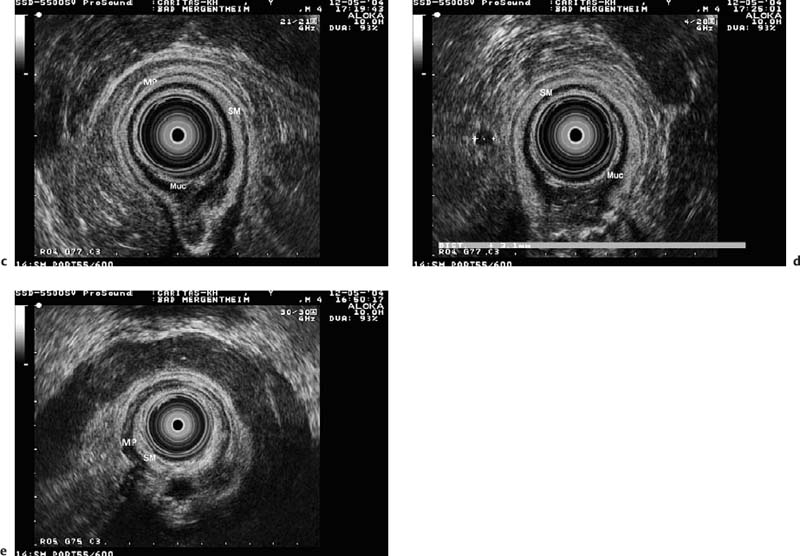

24 Endoanal and Endorectal Sonography Sonographic examination of the perineum, anus, and rectum, including the surrounding structures, using intraluminal transducers ultrasonographywith transanal/rectal imaging—i.e., endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS)—has become increasingly important in clinical practice during the last 10 to 15 years.1–3 Anal and rectal EUS have been shown to be useful tools in evaluating colorectal, anal, and pelvic disorders, due to the high resolution provided, with clearly distinguishable tissue-dependent echo signals.4,5 The use of anal and endorectal ultrasonography is now recommended for a wide variety of indications, on the basis of the diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines published by technical review groups in various societies representing specialties and/or subspecialties.6 EUS is able to image the rectal wall layers and adjacent structures, including the pelvic organs, with a high degree of precision. Detailed knowledge of the anatomy and morphology is needed for correct interpretation of the images provided. Modern intraluminal ultrasound probes make it possible to image the anal and pelvic structures in multiple planes relative to the body-axis, providing sagittal, frontal, transverse, and longitudinal sections. The anal mucosa and internal anal sphincter (IAS) muscle are considered to represent the continuation of the inner rectal ring muscle. They form the innermost structures and can be visualized from the anal lumen. The hyperechoic longitudinal fibers of the corrugator ani muscle are regarded as an extension of the exterior rectal longitudinal muscle. The levator ani muscle is located at the cranial edge of the external anal sphincter (EAS) muscle, which has a funnel like shape and forms the muscular floor of the pelvis. The funnel like structure of the levator ani separates the extraperitoneal pelvis from the infraperitoneal and the pelvirectal space. The lateral region corresponds to the obturator internus muscle. The deep transverse perineal muscle and superficial transverse perineal muscle, as well as the is chiocavernous muscle, can also be imaged with EUS. The transverse orientation is the one most commonly used, and it can be varied depending on the height and angle of the corresponding sections (Figs. 24.1, 24.2, 24.3, 24.4, 24.5, 24.6, 24.7, 24.8, 24.9, 24.10, and 24.11). Anal canal. The echogenicity of the various mural layers in the anal canal is very similar to that in the rest of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by various well-distinguishable bands when imaged from the lumen. The anal canal is covered with columnar epithelium below the anal crypts. The mucosa is a transitional cell epithelium and starts at the level of the anal crypts; however, it can only be visualized irregularly as a faintly dark layer with scattered echoes of medium density. The transitional epithelium disappears in the first echodense border area, depending on the type of ultrasound probe used and the frequency being used. Fig. 24.1a–f Views of the internal anal sphincter (IAS) as the principal structure at the first level from anal to oral, with six horizontal sections (a-f) a few millimeters long, which should be seen as a continuum. a The subcutaneous part of the external anal sphincter muscle is seen as a strong hyperechoic ring. At this level, the IAS is not visible. b-d A hypoechoic inner ring (the IAS) is seen, accompanied by an outer hyperechoic ring representing the external anal sphincter (EAS), with the superficial part initially and the deep part following. LM, longitudinal muscle (the corrugator cutis muscle of the anus); RVP, rectal venous plexus; SM, submucosa. Fig. 24.3 A hypoechoic inner ring (the internal anal sphincter), accompanied by the superficial part of the external anal sphincter (the outer hyperechoic ring). Fig. 24.4 A strong puborectal sling is seen here, which is hyperechoic like all the striated muscles in the external anal sphincter, in contrast to the internal anal sphincter, which is seen as a hypoechoic ring internal to the puborectal sling. Fig. 24.5 The inner hypoechoic ring is formed by the smooth muscle of the internal anal sphincter. There is also an outer hyperechoic ring, representing the strong and circumferentially intact external anal sphincter (striated muscle). Fig. 24.6 The normal prostate gland, situated ventrally. This is a useful landmark during routine endorectal ultrasound examinations. Fig. 24.7 Normal seminal vesicles, situated cranial to the prostate gland. The moustache shape and symmetry of the structure should be noted. Fig. 24.8 A normal pear-shaped uterus, with slight deviation to the left. This is a useful landmark during routine endorectal ultrasound examinations in female patients. Fig. 24.9 The normal vagina, situated ventrally between the bladder (the echo-free urine-filled structure above the vagina) and the rectum. Typically, a three-layer morphology is seen, with a fine hyperechoic inner layer. Fig. 24.10a–c Views of the external anal sphincter (EAS) at the second level from anal to oral, in three sections at very short distances from each other. IAS, internal anal sphincter (seen less prominently); Muc, mucosa; PRM, puborectal muscleand perirectal fatty and connective tissue (i.e., mesorectum); SM, submucosa. Fig. 24.11a–e View at the third level from anal to oral in five sections, with the rectal ampulla as the principal structure, in a patient with proctitis. MP, muscularis propria, with the inner ring (R) and outer (longitudinal) layer (OL), including the perirectal fatty and connective tissue structures; SM, submucosa; Muc, mucosa. Perirectally, a lymph node is visible between the markers in d. The pectinate line and the crypts are often not visible, mainly due to compression of the anal canal by the endorectal probe. The submucosa and subcutaneous connective tissue appear as a homogeneous echogenic layer, increasing in thickness from the superior to the inferior margin of the anal canal. The rectal venous plexus is normally almost invisible unless very thin probes are used. The IAS can regularly be seen as a homogeneous hypoechoic layer with a thickness of 2-4 mm, with no significant sex-dependent differences. However, the thickness measured depends on the probes used, as larger probe diameters lead to thinning of the surrounding structures.7 The echodensity and thickness of the IAS tend to increase with age. However, the normal thickness does not exceed 4 mm even in the elderly. The intersphincteral space, with fibers of the corrugator muscle as a continuation of the rectal longitudinal muscle, is seen endosonographically as a thin hypoechoic layer containing hyperechoic connective-tissue septa, representing the border areas of the hypoechoic IAS and the first less echogenic layer in the EAS. It can be identified at ≈ 2 cm from the anocutaneous line. At this level, the ischioanal fossa, anococcygeal ligament, and coccyx can be visualized, provided that appropriate acoustic penetration is produced. Adequate differentiation is possible in the hyperechoic border area between the ultrasound probe and the mucosa (or the anal cutis): the hypoechoic, extremely thin mucosa, which often cannot be recognized as a defined layer, due to a lack of the muscularis and its very thin diameter; the hyperechoic submucosa (and subcutis); and the hypoechoic IAS, with the adjacent partly hypoechoic and partly hyperechoic intersphincteral space corresponding to the corrugator ani muscle. The EAS contains connective-tissue fibers in increasing amounts toward its distal section and appears as a layer 5-10 mm wide with irregular echo patterns and a series of concentrically bright and gray echo lines, depending on the ultrasound resolution power and, in relation to the thickness, the probe diameter. The EAS continues into the puborectalis muscle at the cranial margin of the anal canal. This part of the puborectalis muscle, with its more echogenic patterns, is only identifiable by its course. More orally, the muscular structures are no longer imaged vertically, so that this part of the muscle produces a weaker and less defined image. Ventrally, this broad muscle layer reaches the inferior part of the pubic bone, with inclusion of the urethra and the inferior part of the prostate or vagina. This typical configuration can be seen in the transverse section at 3 cm from the anocutaneous line between the 10-o’clock and 2-o’clock positions, with visualization of the urethra, prostate, inferior pubic ramus, levator ani muscle (puborectalis muscle), EAS, and ischioanal fossa and pelvirectal fossa. The EAS consists of three more or less separate parts: the subcutaneous part, the superficial part, and the deep part. It is of great importance to understand that the shape and configuration of the EAS differs significantly between males and females. The anal canal is generally 0.5-1.0cm longer in males, and the three different parts of the EAS are configured cylindrically around the anus, which means that the muscle shape and length are roughly the same ventrally and dorsally. In contrast, the three sections of the EAS are fused into a narrow band ventrally at the level of the superficial part in females.8,9 Awareness of this anatomical difference is very important in order not to misinterpret normal anatomical findings. The subperitoneal/pelvirectal layer and the subcutaneous and ischiorectal space are confluent relative to each other. The remaining muscles forming the levator ani muscle (the coccygeus muscle, iliococcygeus muscle, and pubococcygeus muscle) are identifiable with EUS only to a limited extent, but can be seen as an inhomogeneous, mostly hyperechoic layer with increasing cranial distance to the rectal wall. It is important to appreciate that the hyperechoic structures are not directly imaged, but instead represent ultrasound artifacts indicating borderline areas behind which the real anatomical structures are imaged, such as the mucosa and muscularis propria—especially when older ultrasound equipment is used. In addition, it is also clinically relevant to note that these two hypoechoic structures are important in the staging of rectal cancers in accordance with the TNM classification. The anatomical relationship between the IAS, levator ani, and ischioanal/iliorectal fossa can only be reconstructed if the operator is sufficiently familiar with the anatomy and has a good spatial imagination. Reproducible documentation and visualization in a single image are only possible with the aid of longitudinal sonographic sections through the anal canal. Systematic and comprehensive categorization can be achieved formally by producing corresponding sections at a superficial level at 0-2 cm, at a second level at 2-4cm, and at a deeper level >4cm above the anocutaneous line. For learning purposes, a step-by-step approach centimeter by centimeter appears helpful.

Anatomy of the Perineum and Anus

Anatomy of the Perineum and Anus

Endosonographic Imaging at Different Anatomical Levels

Endosonographic Imaging at Different Anatomical Levels

Internal anal sphincter muscle |

External anal sphincter muscle • Subcutaneous part • Superficial part • Deep part |

Levator ani muscle |

Obturator internus muscle |

Deep and superficial transverse perineal muscle |

Ischiocavernous muscle |

Muscle | Depth |

Internal anal sphincter | 1.5-4.0 mm |

External anal sphincter | 5-10 mm |

Internal anal sphincter level. The first section shows the cutis, the transitional epithelium, and the subcutis with the transition to the submucosa, and more orally the IAS surrounded by the transverse perineal muscle and the ischioanal fossa. At this level, the corrugator ani (or longitudinal) muscle, containing hyperechoic connective-tissue fibers, can be distinguished from the IAS, which has weaker echogenicity (i.e., a hypoechoic pattern). Additional points of orientation at this level are the root of the penis with the ischiocavernous muscle and the ramus of the ischium.

External anal sphincter level. The second section shows the less pronounced hypoechoic IAS, and as the principal structure the more prominent EAS with inhomogeneous echo patterns (with a series of concentrically bright and gray areas or lines); more in the distance and posteriorly, the coccyx and coccygeal ligament (the dural part of the filum terminale) are seen. The anorectal muscles delineated with ultrasound are listed in Table 24.1, and normal sphincter values are listed in Table 24.2.

Rectal wall. The third section is at the level of the prostate gland with the urethra; the inferior pubic ramus yields images of the lumen and the variably hyperechoic EAS at an increasing distance, and the transition into the levator ani muscle forming the pelvic floor. The funnel of the levator ani separates the extraperitoneal pelvis into an infraperitoneal or pelvirectal space and a subcutaneous or ischiorectal space. The lateral border corresponds to the obturator internus muscle, with the obturator foramen. At this point, which is distinctly marked by the U-shaped puborectalis, the anal canal terminates and the rectum begins.

A transverse section with a 360° transducer is helpful for examining the anal canal, whereas for examining more orally located structures, radial as well as sector scanners can be used. Most modern probes, however, provide 360° transducers, which makes orientation much easier.

Patient preparation. Before rectal/anal EUS is performed, the patient’s history should be carefully noted, with subsequent digital examination, and sigmoidoscopy (rectoscopy, colonoscopy) should be carried out to evaluate potential obstacles (contraindications) and obtain important additional information. No special bowel lavage is needed, except for the application of a cleansing enema 10-20 minutes before a rectal examination. An enema is not required if only the anal canal is examined (e.g., sphincter evaluation in incontinent patients or patients with anal fistulas). The patient is examined either in the left lateral or the lithotomy position, depending on the examiner’s preference. However, reporting of the findings should always use clock points for reference (the pubic symphysis is always at the 12-o’clock position).

Introducing the transducer. Before the ultrasound probe is introduced, a thin layer of jelly is applied to the transducer’s outer protective latex cover. The probe itself can either be introduced “blindly,” or with the palpating finger, or using a rectoscope (rarely performed). Optimal viewing of the perianal and perirectal processes is achieved when the transducer is directed toward the umbilical region. When lower frequencies are used, a filling balloon may be helpful, but in this case it has to be taken into account that the degree of filling of the water balloon may affect the imaging of the rectal wall and/or pathological processes. Water filling is not required if only the anal region is examined. The rectal wall may be stretched, depending on the extent of the filling, resulting in compression of the single wall layers. Even a tumor can then be overlooked if inappropriate pressure is applied. As in rigid rectoscopy, problems may arise starting at 15 cm above the anocutaneous line. However, there are cases in which viewing with the rigid instrument is already hampered at a level at or just above 10 cm, particularly when the examination is being conducted to search for a tumor. In normal circumstances, the rigid probe can be advanced up to 20 cm above the anocutaneous line.

Examination. It should be emphasized that EUS is not an appropriate screening test in the way that endoscopy is— for example, for detecting hitherto unknown tumors or other types of pathology. EUS is a supplementary examination intended to provide additional clinical information in a patient’s diagnostic work-up. In the case of a rectal tumor, for instance, EUS serves as a staging tool; in a patient with fecal incontinence, it is used to examine the sphincter morphology, and so forth. The ultrasound examination is carried out during slow, step-by-step withdrawal of the transducer into the anal canal. Orientation is achieved by identifying the principal surrounding structures (bladder, prostate, vagina, puborectal muscle, etc.); details are best seen with appropriate focusing and adjustment of the instrument.

Clinical Indications for Endorectal Ultrasound Techniques

Whereas rectal EUS primarily visualizes the rectal wall layers and their surroundings, the purpose of anal EUS examinations is to investigate the sphincter muscles and pelvic floor. Due to the variability of the organ structures and the complex conditions affecting the precise location of the organs, detailed anatomical knowledge and precise orientation are mandatory for correct interpretation of EUS images. Starting from the lumen, a thin hypoechoic circular structure and a thicker hyperechoic circular structure are seen, which are interpreted as border echoes and subepithelial tissue, respectively, followed by a hypoechoic homogeneous ring pattern, which corresponds to the IAS. This muscle is usually thickest at the level of the pectinate line, with the diameter decreasing in the oral direction. The superposed longitudinal muscle is not always clearly visible with relatively hypoechoic fibers. The EAS consists of horizontally oriented (striated) fibers with complex, mainly hyperechoic structures (see Fig. 24.3). At the outermost level—i.e., immediately at the anocutaneous junction—the IAS is not visible. Only the subcutaneous portion of the EAS forms the sphincter apparatus at this level, which is recognized by a strong circular band with the typical hyperechoic pattern of striated muscle. More orally, the structures of the levator ani and puborectalis muscle can be seen, the latter passing the rectum dorsally in a U-shaped loop and continuing ventrally as two lateral crura to the pubic bone. Sonomorphologically, these structures are represented by inhomogeneous longitudinal echo patterns lateral to the sphincter organ (see Fig. 24.4). At this level, the adjacent organs (prostate, seminal glands, urethra, vagina, uterus, and bladder) are also visualized. The indications for anorectal ultrasonography (ARUS) and endorectal ultrasonography (ERUS) are listed in Table 24.3.

Clinically, rectal cancer is regarded a separate entity, which can be distinguished from colon cancer on the basis of the surrounding anatomy, despite a similar pathogenesis. The treatment options also vary distinctly between rectal and colon cancers—including local excision and neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, for example. Accurate preoperative staging using EUS is therefore mandatory in order to allow an individualized approach to treatment in rectal cancer patients.

T and N staging. Precise preoperative assessment of the tumor’s penetration depth (T staging) is possible with EUS; the endosonographically assessed tumor stage is labeled with the prefix “u” for ultrasound (Figs. 24.12, 24.13, 24.14, 24.15, 24.16, 24.17, 24.18, 24.19, 24.20, 24.21, 24.22, and 24.23). uT1 carcinomas are present when the mucosa/submucosa is involved, the second layer (hypoechoic) is often thickened, and the subsequent hyperechoic layer (layer III) is still intact. In uT2 tumors, the fourth (hypoechoic) layer, corresponding to the muscularis propria, is enlarged, with interruption of the layer located immediately below (III) and hypoechoic thickening of the mucosa (layer II); the outermost layer (V) remains intact. In uT3 tumors, each of the wall layers is involved, including layer V, with extension into the hyperechoic perirectal fat tissue. The continuity of layer V is disrupted. In stage T4, the tumor infiltrates either neighboring organs (such as the prostate, vagina, or bladder), which can be visualized easily with EUS, or the visceral peritoneum, although the latter is not distinguishable as a separate layer. Other malignant and nonmalignant processes can be examined with EUS and provide important additional information. Tumor recurrences (at the anastomosis or perirectal), recurrences in the pelvic floor, tumors in the lower pelvis (e.g., uterus, vagina, or bladder), transmural inflammatory processes (Crohn disease of the colon) and/or fistulas are also accessible to EUS, as well as other forms of disease (Figs. 24.24, 24.25, 24.26, and 24.27).10

Anal carcinoma | T and N staging |

Rectal carcinoma |

Rectal Cancer

Rectal Cancer Tumor Staging

Tumor Staging