The objective of this chapter is to review the radiologic findings of this relatively common disease, which causes significant morbidity and infertility in women of childbearing age.

Disease

Definition

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of hormonally functional endometrial tissue outside the uterus. Endometriosis occurs most commonly on the serosal surface of the uterus and ovaries but can involve the peritoneal surface anywhere in the abdomen, including the peritoneal surfaces of other pelvic and abdominal organs. Endometriosis can also be found outside the abdomen and pelvis in distant locations such as the lung and the central nervous system.

Two forms of endometriosis have been described:

- 1.

Diffuse: The most common form, which consists of tiny endometrial implants that are difficult to diagnose with imaging because of their small size

- 2.

Localized: Discrete masses, called endometriomas , which have characteristic imaging appearances

Prevalence and Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of endometriosis is difficult to determine accurately because patients may be asymptomatic. The reported prevalence varies with mode of diagnosis, ranging from 2% to 18% in the general population to 5% to 10% in women with infertility.

Endometriosis occurs predominantly in women of childbearing age. The mean age at diagnosis is 25 to 29 years, and a 10-fold increase in prevalence has been observed in women with an affected first-degree relative. Hereditable tendencies have been recognized with increased risk for developing endometriosis of 5% to 7% for first-degree relatives.

Several studies have suggested that Asian women are at higher risk and African-American women have a lower risk for developing endometriosis.

Endometriosis is the third leading cause of gynecologic hospitalization in the United States.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Multiple theories have been proposed to explain the development of endometriosis ( Figure 9-1 ). The most prevalent theory regarding the etiology of endometriosis is retrograde menstruation with migration of endometrial cells through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity and subsequent implantation onto peritoneal surfaces. This was first described by Sampson in 1927 and in subsequent articles, in 1940, and is substantiated by the observation that endometriosis is more prevalent in women with excessive retrograde menstrual flow resulting from obstructive congenital müllerian duct anomalies. Additionally, endometrial implants are most commonly found in dependent areas of the pelvis where refluxed endometrial tissue and blood would be expected to accumulate.

Direct implantation of endometrial tissue during surgical procedures like cesarean section or other forms of uterine surgery has also been postulated as a cause of endometriosis.

Because endometrial implants have also been described outside the peritoneal cavity in the lungs and central nervous system, the possibility of dissemination and spread of endometrial cells through blood vessels and lymphatics has also been proposed. First postulated by Sampson and Halban in the 1920s, this theory can explain the rare cases of endometrial implants reported in bone, muscle, brain, lung parenchyma, and the intervertebral disk spaces.

Coelomic metaplasia is the least commonly accepted theory and was proposed at the turn of the century by Meyer. This theory suggests that stimulation of the peritoneal epithelium by infection, hormones, or other unknown etiologies can result in conversion into endometrial epithelium. Clinical findings of endometriosis in men, prepubertal girls, women with Turner’s syndrome (absent uteri), and unusual sites like the pleural cavity have been cited as evidence to substantiate this theory.

Genetic factors are also thought to play a role in the development and progression of the disease. The role of the immune system has also been questioned because activity of peritoneal natural killer and T lymphocytes is suppressed in women with endometriosis. It is likely that there are multiple causes of endometriosis, and the etiologies described above may not be mutually exclusive (see Figure 9-1 ).

Irrespective of the exact cause of endometriosis, the ectopic endometrial tissue responds to hormonal stimulation and undergoes repeated cycles of hemorrhage, resorption, fibrosis, and scarring, which eventually result in the development of adhesions, endometriomas, and symptoms.

The most common organ of involvement in the pelvis is the ovary. Other common locations include the uterine suspensory ligaments, cul-de-sac, pelvic peritoneal surfaces, fallopian tubes, rectosigmoid colon, and bladder. Less common sites include the umbilicus and cesarean section or abdominal wall scars ( Figure 9-2 ).

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients with endometriosis most commonly present with pelvic pain that is often recurrent or cyclical (dysmenorrhea), coinciding with the patient’s menstrual cycle. The pain is believed to be a result of peritonitis caused by bleeding from the ectopic endometrium under hormonal stimulation. Adhesions may also cause pain. The severity of the pain is not directly related to the size or number of implants, adhesions, or endometriomas. Often large endometriomas may be asymptomatic, and relatively few tiny implants and/or adhesions may cause severe, excruciating pain. Dyspareunia and pain with defecation may also occur.

Infertility may result from pelvic adhesions, and occasionally adhesions may cause bowel obstruction. Rarely catamenial pneumothorax or recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage can be caused by lung or central nervous system involvement.

The disease can be physically and mentally debilitating because symptoms can be nonspecific, and as a result misdiagnosis or delay in diagnosis is common.

The time between the onset of symptoms to a confirmed diagnosis may average 6 years or more.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

The value of imaging is limited because it is difficult with any imaging modality to visualize adhesions and implants smaller than 3 mm in diameter, which nonetheless may cause severe pelvic pain. Therefore laparoscopy remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis and staging.

The revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis is based on a point system scored by visual inspection :

Stage 1: Minimal 4 to 5 points

Stage 2: Mild 6 to 16 points

Stage 3: Moderate 16 to 40 points

Stage 4: Severe 40 points

The gross appearance at surgery is characteristic and sufficient for diagnosis with an experienced surgeon. The smallest visible implants appear as red petechial lesions on the peritoneal surface. Further growth results in a cystic dark brown, dark blue, or black appearance. The surrounding peritoneal surface becomes thickened and scarred, giving a “powder burn appearance.” These implants are usually 5 to 10 mm in diameter, and with progression, adhesions between adjacent structures may develop.

On the ovary, these cystic lesions continue to grow and become endometriomas or “chocolate cysts,” which subsequently may rupture and seal off. Perpetuation of the process under cyclical hormonal stimulation results in multiplicity.

Ultrasound (US) is usually the first imaging modality of choice for the evaluation of women who present with pelvic pain because it is noninvasive and does not carry the risks of ionizing radiation or intravenous contrast exposure. US is also relatively inexpensive and readily available to the general population. Endometriomas can be recognized on US examination, but adhesions and/or small implants are rarely visualized.

Computed tomography (CT) is sometimes the initial imaging modality ordered in patients with pelvic pain and/or abdominal symptoms, but if there are ovarian masses, the findings are usually nonspecific.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging gold standard for the diagnosis of endometriosis and should be the initial examination obtained in patients when there is strong clinical suspicion. MRI is highly accurate in the diagnosis of endometriosis largely because of the unique behavior of hemorrhage on MRI.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Radiography

Currently plain films have no role in the diagnosis. Fluoroscopy and barium enema may demonstrate complications such as colonic strictures, adhesions, and/or implants ( Figure 9-3 ).

Ultrasound

The sensitivity and specificity of US for the diagnosis of endometriomas are reported to be 83% to 89%. US, however, has a limited role and sensitivity for the identification of small implants (<1 cm) and peritoneal adhesions. In some patients, the presence of adhesions can be indirectly inferred by the lack of uterine mobility because US is a dynamic imaging modality, or by blurring of the serosal surface of the uterus and/or ovaries.

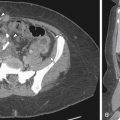

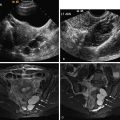

The classic sonographic appearance of an endometrioma is as follows: a cystic adnexal mass separate from the ovary containing diffuse low-level homogenous echoes often described as a “ground glass” appearance ( Figure 9-4 ). The lesion contours are often angular as a result of adhesions or fibrosis. Often there is a conglomeration of multiple cysts with angular margins ( Figure 9-5 ). Lesions, however, are usually monolocular and rarely have septations. Color and spectral Doppler interrogation will not demonstrate internal vascularity.

Rarely, layering with fluid–fluid or fluid–debris levels may be observed. More often a graduated change in echogenicity from an anechoic appearance superiorly to a more echogenic texture dependently can be seen. This has been described as “shading” and is likely caused by suspension of the gradually settling red blood cells or blood products within the gelatinous contents of the endometrioma ( Figure 9-6 ).

Echogenic foci may be noted in the walls of endometriomas. The exact pathologic basis of these foci has not been established. Given the similarity to hyperechoic gallbladder wall foci in hyperplastic cholestasis, it has been postulated that they may contain cholesterol from the breakdown of cell membranes ( Figure 9-7 ).

Dilatation of the fallopian tubes, usually filled with echogenic material, can be seen on US examination. The findings, however, are nonspecific because US cannot definitively differentiate intraluminal echogenic material caused by hematosalpinx from pyosalpinx or even debris ( Figure 9-8 ).

Computed Tomography

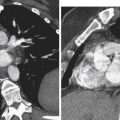

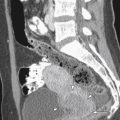

CT is not used as a screening or definitive diagnostic modality. The findings on CT are often incidental when the patient is imaged for other suspected causes of abdominal or pelvic pain. Mixed density adnexal masses (endometriomas) ( Figure 9-9 ), soft tissue nodules in the anterior abdominal wall, and dilated fallopian tubes may be evident on CT ( Figure 9-10 ).

Magnetic Resonance

For endometriosis, MRI has a reported sensitivity ranging from 71% to 90% and specificity of 82% to 98%. T1- and T2-weighted sequences along with fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequences are most useful. Diagnostic accuracy is higher with fat suppression (77%) than with conventional images (55%). The former excludes fat-containing adnexal masses and increases lesion conspicuity. Intravenous contrast is usually not required except when evaluating for malignancy.

Endometriomas represent adnexal masses on the surface of the ovary and are usually multiple and bilateral. Endometriomas are also known as chocolate cysts because of the dark material seen at gross pathology, which are blood products in various stages of degradation. The loss of signal on T2 is due to high concentrations of intracystic methemoglobin and other protein or iron products.

Free water resorption increases the viscosity and iron content of the cysts. They may have a peripheral rim of low signal intensity representing a fibrous capsule. Enhancement of the periphery or adjacent peritoneal surfaces may occur. They may predispose the ovary to torsion, although less commonly than other masses possibly because of surrounding adhesions.

On MRI, endometriomas exhibit signal consistent with hemorrhage, most commonly hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted sequences ( Figure 9-11 ).