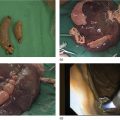

José Celso Ardengh1, Juan Pablo Román Serrano2, Samuel Galante Romanini2, Juliana Silveira Lima de Castro2, and Isabela Trindade Torres2 1 Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo, Brazil; Endoscopy Service Hospital 9 de Julho, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2 Endoscopy Service Hospital Nove de Julho, Sao Paulo, Brazil, Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) identifies pelvic diseases besides rectal cancer and fecal incontinence. In this context, endometriosis can be identified and classified by changing the therapeutic strategy to be adopted. Transrectal EUS can identify and stage prostate cancer. Although this indication is not part of the daily clinical practice of medical specialists in the United States, in this chapter we focus on pelvic endometriosis since it can affect the gastrointestinal tract in 3–37% of severe cases. Endometriosis is the presence of ectopic endometrial stroma outside of the endometrial cavity. Microscopically, it may be associated with macrophages full of hemosiderin; macroscopically, it appears as pigmented (typical) or non‐pigmented (atypical) brown, red, or black lesions. It affects approximately 10% of women of childbearing age. It can be deep or extensive and affect adjacent organs such as the rectum and/or sigmoid colon, the bladder, and the ureters. When it invades the ovary, this is known as endometrioma. This disease is multifocal, and the main locations affected are the pelvic peritoneum (ovarian cavity and uterosacral ligament) and the pelvic organs (ovaries, fallopian tubes, bladder, sigmoid colon, and rectum), although sites of endometriosis can also be found in the liver, lungs, pleura, and other organs. The sites most affected by extragenital endometriosis are the rectum and the sigmoid colon (85% of cases), followed by the cecal appendix and small intestine. It is estimated that 3–10% of the women in their fertile period have endometriosis. Around 30% can be infertile, and approximately 50% experience chronic pelvic pain. Occurrence in black women is lower than in white women. The diagnosis may be given in the third decade of life. A low body mass index and anxiety levels higher than average are characteristic of the disease. Late diagnosis favors a poor quality of life due to chronic pain, with implications for day‐to‐day work, and manifests high rates of infertility. Risk factors include: The protective factors include smoking, use of contraceptives, multiparity, and early first pregnancy (<18 years). Progressive dysmenorrhea, chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, infertility, and intestinal and urinary abnormalities during menstruation are common symptoms. With respect to intestinal abnormality, it is relevant to mention change in intestinal habit (constipation and diarrhea), abdominal distress and/or distension, and cyclical bleeding (hematochezia). The medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests can diagnose the presence of endometriosis. Confirmation is provided by histopathological analysis through video‐laparoscopy, while tests for CA‐125 (up to 35 U/ml), carried out between the first and third day of the menstrual cycle, are also helpful in diagnosis. CA‐125 sensitivity is higher in stages III and IV endometriosis with extensive disease, adhesions or endometriomas. This test is therefore recommended for monitoring and treatment. The serum amyloid A protein (up to 5 U/ml) is specially requested when intestinal disorder is suspected. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine classifies endometriosis according to size, depth, and location in four stages. Abdominal and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), transrectal ultrasound, EUS, and video‐laparoscopy help in the diagnosis because they have high accuracy. Pelvic and transvaginal ultrasound can be normal or reveal ground‐glass cysts, but experienced clinicians can determine the involvement of the intestinal wall, including the layers, and good intestinal preparation helps to identify the ectopic spots and determine the intestinal extension of the disease, facilitating the surgical approach. After transvaginal ultrasound, MRI is considered second line for staging of the disease. The examination is divided into two steps.

17

Endometriosis

Introduction

Definition and location

Epidemiology and risk factors

Clinical picture

Diagnosis

Classification

Imaging methods

EUS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree