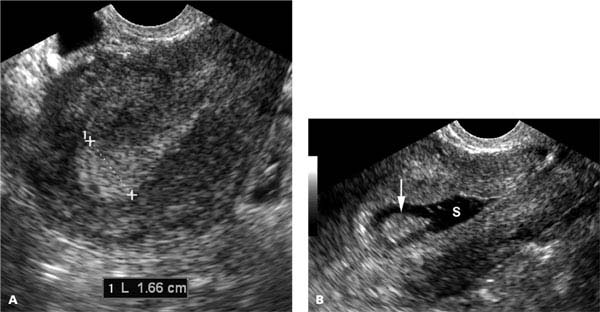

Figure 27.1.1

Endometrial polyp. A: Sagittal transvaginal view of the uterus demonstrates a homogeneously echogenic mass (calipers) in the endometrium, representing a polyp. B: Color Doppler demonstrates a single feeding vessel (arrow) into the polyp.

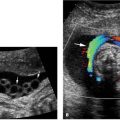

Figure 27.1.2

Endometrial polyp containing cysts. A: Sagittal and (B) coronal transvaginal views of the uterus demonstrate several cysts (C) in the endometrium (arrowheads), suggesting that the structure filling the endometrium is a polyp. C: Color Doppler reveals a single feeding vessel into the polyp (arrow).

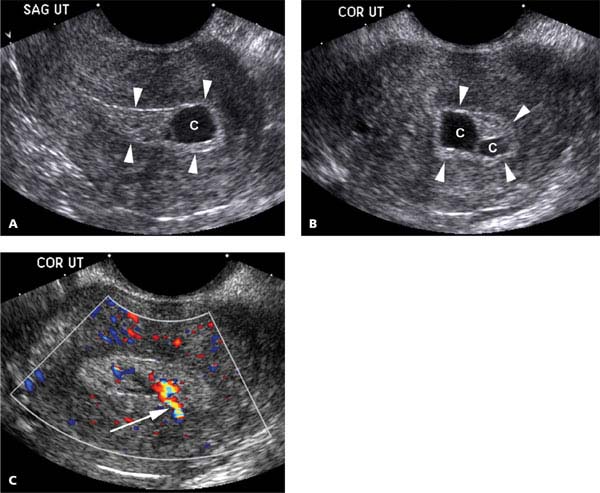

Figure 27.1.3

Endometrial polyp surrounded by fluid. A: Sagittal transvaginal view of the uterus demonstrates a polypoid projection of tissue (arrow) surrounded by fluid (F) in the uterine cavity. The fluid likely represents blood or secretions. B: Color Doppler demonstrates a single feeding vessel (arrow) into the polyp.

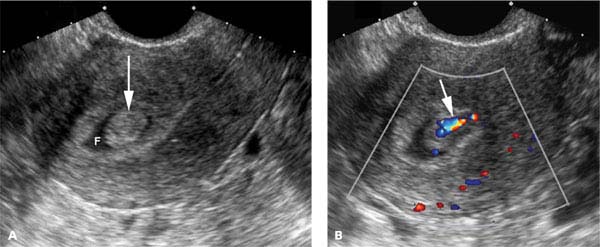

Figure 27.1.4

Endometrial polyp depicted by saline infusion sonohysterography. A: Sagittal midline transvaginal view of the uterus demonstrates focal homogeneous thickening of the endometrium (calipers), measuring 16.6 mm in thickness, at the fundus. B: After instillation of saline, a polyp (arrow) is seen projecting into the fluid (S) in the uterine cavity.

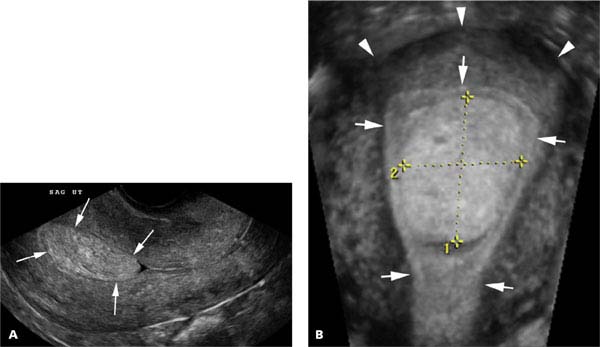

Figure 27.1.5

Endometrial polyp depicted by 3D sonography. A: Sagittal midline transvaginal view of the uterus demonstrates a rounded mass in the endometrium (arrows). B: Coronal reconstruction from 3D ultrasound clearly demonstrates that the mass is a polyp (calipers) within the endometrium (arrows). The fundus is at the top of the image (arrowheads).

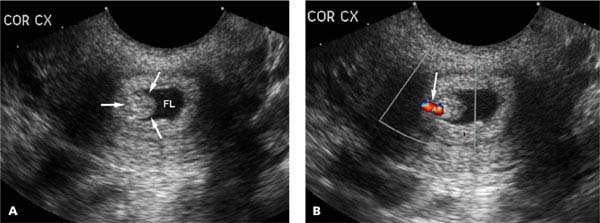

Figure 27.1.6

Cervical polyp. A: Coronal transvaginal view of the cervix demonstrates a polypoid soft tissue mass (arrows) outlined by fluid (FL) in the cervical canal. B: Color Doppler demonstrates a single feeding vessel (arrow) into the polyp.

27.2. Endometrial Hyperplasia

Description and Clinical Features

Endometrial hyperplasia refers to abnormal proliferation of the endometrial glands. It is usually caused by unopposed estrogen stimulation, which can result from estrogen given as hormone replacement therapy, hormonal disorders (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome), or estrogen-producing tumors.

Hyperplasia is usually a diffuse endometrial process. It can occur with or without cellular atypia. If cellular atypia is present, there is a risk of progression to endometrial carcinoma. The risk is far lower in the absence of atypia.

Endometrial hyperplasia can occur in women of any age. It generally presents with abnormal vaginal bleeding and is among the most common causes of such bleeding.

Sonography

The typical sonographic appearance of endometrial hyperplasia is homogeneous endometrial thickening (Figure 27.2.1). It is best detected when the normal endometrium should be thin. In a premenopausal woman, this occurs during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. During the secretory phase of the cycle, the presence of endometrial hyperplasia is likely to be missed sonographically, because hyperplastic endometrium and normal secretory endometrium have similar sonographic appearances.

In a postmenopausal woman not on hormone replacement therapy, the sonogram can be performed at any time. In a postmenopausal woman on sequential hormone replacement therapy, the findings of endometrial hyperplasia can best be seen shortly after progesterone withdrawal bleeding, when the endometrium is expected to be at its thinnest.

When ultrasound demonstrates diffuse thickening of the endometrium, endometrial hyperplasia should be included in the differential diagnosis, along with endometrial polyps and carcinoma. In these cases, SIS can provide additional diagnostic information. With endometrial hyperplasia, the saline-filled uterine cavity is surrounded in its entirety by thick endometrial tissue (Figure 27.2.1), ruling out a focal lesion such as a polyp. A definitive diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, however, can only be made by tissue sampling (office biopsy or dilation and curettage).

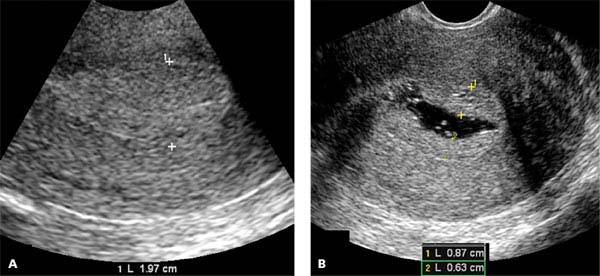

Figure 27.2.1

Endometrial hyperplasia. A: Sagittal transvaginal view of the uterus demonstrates thickening of the endometrium (calipers), which is fairly homogeneous in appearance. B: After instillation of saline into the uterine cavity, the endometrium (calipers) is seen to be diffusely thick, consistent with endometrial hyperplasia.

27.3. Endometrial Carcinoma

Description and Clinical Features

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common malignancy in women in the United States, and the most common pelvic gynecologic malignancy. Most cases occur in women older than the age of 50, and thus it is mainly a disease of postmenopausal women. The typical presenting symptom is abnormal vaginal bleeding, which, after menopause, refers to any bleeding other than that occurring at the expected time in the menstrual cycle of a woman on sequential hormone replacement therapy.

Approximately 10% of postmenopausal women with abnormal vaginal bleeding have endometrial carcinoma. The cause of the bleeding in the remaining 90% is either another form of endometrial pathology (e.g., polyps or hyperplasia) or endometrial atrophy. The definitive diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma can only be made from a tissue sample, which is obtained by endometrial biopsy.

Sonography

The use of ultrasound in relation to endometrial cancer is mainly in women with postmenopausal bleeding, where it serves two main functions: (1) if the endometrial thickness is <4–5 mm, then endometrial atrophy is highly likely to be the cause of bleeding and biopsy is probably unnecessary; (2) if the endometrial thickness is >4–5 mm and endometrial biopsy is planned, SIS can help choose the appropriate biopsy method: if the abnormality is focal, a hysteroscopically guided biopsy may be needed, whereas a blind biopsy is likely to be adequate if the abnormality is diffuse.

Endometrial cancer must be considered in the differential diagnosis when the endometrial thickness is >4–5 mm in a postmenopausal woman with vaginal bleeding (Figures 27.3.1 to 27.3.3). The likelihood of cancer goes up progressively with increasing endometrial thickness. Other features suggesting malignancy include a lobular endometrial contour, which can best be seen if there is fluid in the uterine cavity (Figure 27.3.2), or an ill-defined endometrium–myometrium interface (Figure 27.3.3).

Figure 27.3.1

Endometrial carcinoma. Sagittal transvaginal view of the uterus in a postmenopausal woman demonstrates a markedly thickened endometrium, measuring 5.03 cm (calipers). Biopsy revealed endometrial carcinoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree