16 Endoscopic Ultrasound in Chronic Pancreatitis Difficulties in Diagnosing Chronic Pancreatitis Establishing a definite diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is a challenging task. The definition of the diagnosis itself is already problematic—for example, it is often not possible to differentiate clearly between recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis and the early stages of chronic pancreatitis. The history and presenting symptoms may be nonspecific, which may result in up to four in every 10 patients being initially misdiagnosed as “nonspecific dyspepsia.”1 The correct diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is, on average, only made 60 months after the original presentation.2 Simple pancreatic function tests (e.g., fecal pancreatic elastase) and widely available noninvasive imaging methods such as abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) are not sufficiently sensitive to diagnose the early stages of chronic pancreatitis. Percutaneous biopsy of the pancreas can be used to confirm a suspected diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. However, it is a very invasive method, and since the extent of disease may vary widely within different areas of the pancreas, it may not necessarily be diagnostic. Its routine use is not recommended. Up to now, a combination of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and the secretin-pancreozymin test has been regarded as the reference standard for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis.3 However, ERCP does carry a considerable procedural risk, is unpleasant for the patient, and is very expensive.4–6 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is so far not being used routinely, but it appears to be a promising method for the future.7 In chronic pancreatitis, functional deficits, morphological changes, and the degree of pain are not always closely correlated. The extent of changes in the pancreatic duct system and the extent of impairment of the exocrine function correlate closely in only about 75% to 80% of patients.2,8 There are patients with severely damaged pancreatic ducts who have normal exocrine and endocrine pancreatic function, and some of these patients may be completely asymptomatic for years. In contrast, clinically significant impairment of pancreatic function does not have to be associated with severe ductal changes. Some 5–10% of patients with chronic pancreatitis are initially pain-free and only develop symptoms later on due to endocrine and exocrine dysfunction.2,4,8 It is difficult to judge the significance of mild or early changes in the pancreatic duct system and the pancreatic parenchyma, particularly because the normal appearance of the pancreas already varies widely with age. It may also be impossible to differentiate early chronic pancreatitis from scarring after acute pancreatitis, and from asymptomatic fibrosis of the pancreas.3–5,9 In up to 30% of cases of chronic pancreatitis or recurrent acute pancreatitis, it is not possible to determine the etiology of the disease, despite a detailed history and extensive investigations.8,10 Even if a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is established, it may still be difficult to determine the exact nature of focal cystic or solid changes within the pancreas.11 The following imaging methods are available for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis and its complications: • Radiographic methods: plain radiography, computed tomography (CT) • Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) • Endoscopic methods: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) • Abdominal ultrasonography (US), possibly with color-coded duplex sonography (CCDS). Chronic pancreatitis can be diagnosed with abdominal ultrasound in accordance with the criteria used in the Cambridge classification. This classification uses a combination of diagnostic criteria, each of which in itself is nonspecific (Table 16.1).2,5,12,13 In contrast to ERCP, which only allows investigation of the ductal system, ultrasound allows visualization of both the ductal system and of the pancreatic parenchyma. In addition, it is noninvasive, the patient is not exposed to X-rays, and, at least in theory, ultrasound should also be able to detect any complications of acute and chronic pancreatitis, particularly if it is used with CCDS.13–22 However, in comparison with the reference standard of ERCP and the secretin-pancreozymin test, the sensitivity of abdominal ultrasound is relatively low (60–70%), to a large extent probably due to the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas.5,16,17,23 The sensitivity of abdominal ultrasound is particularly low for diagnosing the early stages of chronic pancreatitis.

Stage | ERCP | Abdominal ultrasonography, CT |

Normal (0) | No pathological changes; good-quality study of the entire pancreatic duct system must be obtained | No pathological changes (main pancreatic duct < 2 mm, homogeneous parenchymal structure, normal size and shape) |

Uncertain (1) | Normal main pancreatic duct, pathological changes in fewer than three side branches | One pathological change: • Main pancreatic duct 2–4 mm • Pancreas enlarged (up to twice normal size) |

Mild (2) | Normal main pancreatic duct, pathological changes in more than three side branches | Two or more pathological changes: • Cysts < 10 mm • Irregular main pancreatic duct • Focal acute pancreatitis • Heterogeneous parenchymal structure • Hyperechoic pancreatic duct wall • Contour irregularities (pancreatic head or body) |

Moderate (3) | As “mild,” plus abnormal main pancreatic duct | All of the criteria mentioned above |

Severe (4) | As “moderate,” plus one or more of the following changes: • Cysts > 10 mm • Pancreas more than twice the normal size • Intraductal filling defects • Pancreatic duct calculi/calcifications • Duct obstruction (stricture) • Severe dilation or irregularities of the main pancreatic duct • Involvement of adjacent organs (ultrasound, CT) |

|

Endosonography of the Pancreas

In virtually all patients with normal upper gastrointestinal anatomy, EUS makes it possible to visualize the entire pancreas, the neighboring blood vessels, and the common bile duct from various scanning positions in the stomach and duodenum. This is not possible with abdominal ultrasound, and the local resolution provided by the endosonographic images is unsurpassed by any other imaging method. Despite there being some technical differences, this applies to both radial and curvilinear endosonography.9,24–28 The large majority of published data were obtained with mechanical radial scanning echoendoscopes with a transducer frequency of 7.5 MHz. In addition, electronic curvilinear, and more recently electronic radial scanning echoendoscopes also allow visualization of the large vessels adjacent to the pancreas with CCDS, and, by using ultrasound contrast enhancement, they may show perfusion as well as pathological changes within the parenchyma of the pancreas.29–38

Because of the anatomical position of the stomach, the endosonographic appearance of the pancreas when viewed with a curvilinear-array transducer resembles its appearance when viewed with abdominal ultrasound. In addition, it is possible to view different planes of the pancreatic head by positioning the transducer in the duodenum25,26,28,39 (Fig. 16.1).

In contrast to ERCP, with endosonography it is not only possible to view changes in the pancreatic duct, but changes in the parenchyma can also be taken into account for diagnostic considerations. The procedural risk of EUS is, however, much lower than that of ERCP. Limitations may arise, as with ERCP, in patients with pyloric stenoses or after surgery, particularly after complete resection of the stomach.

The normal endosonographic appearance of the pancreas is characterized by specific criteria for size, contour, parenchyma, and ducts (Table 16.2)9,25,26,28,40 However, since the imaging planes are less standardized than in CT, for example, the diameter of the pancreatic head has limited diagnostic significance.

To be able to diagnose pathological changes in the pancreas, it is also important to be aware of normal anatomic variants. For example, the width of the pancreatic duct and the echogenicity of the parenchyma increase with age.9,43 Hyperechogenicity in the pancreatic parenchyma has been observed in ≈ 25% of EUS investigations and was found to be related to age, to a higher body mass index, liver steatosis, and to a regular in take of more than 14 galcohol per week.41,42 In addition, the ventral part (the embryological “ventral anlage”) of the pancreas sonographically appears as a variably well-demarcated hypoechoic structure situated in the dorsal and inferior part of the pancreatic head, and may be detected in about 75% of patients undergoing EUS for nonpancreatic indications.44 Detection of the ventral anlage on EUS is less likely in patients with diabetes mellitus, with the sonographic features of chronic pancreatitis, with a mass lesion in the pancreatic head, or with pancreas divisum44–46 (Fig. 16.2).

With some experience, it is also possible to diagnose anatomic variants of the pancreatic duct. Pancreas divisum is present if the course of the pancreatic duct cannot be followed from its origin at the ampulla of Vater through the ventral part to the dorsal part of the pancreas, or if the pancreatic duct cannot be visualized within the ventral part of the pancreas. Architectural distortion due to chronic pancreatitis may favor false-positive diagnoses of pancreas divisum.47–49 It may also sometimes be possible to visualize the separate orifices of the common bile duct at the major papilla and of the dorsal pancreatic duct at the minor papilla (Fig. 16.3c). Conversely, it is possible to exclude pancreas divisum reliably using endoscopic ultrasound if it is possible to follow the pancreatic duct continuously from the ventral to the dorsal pancreas, or between the papilla of Vater and the pancreatic neck9,48,49 (Figs. 16.2a and 16.3a, b).

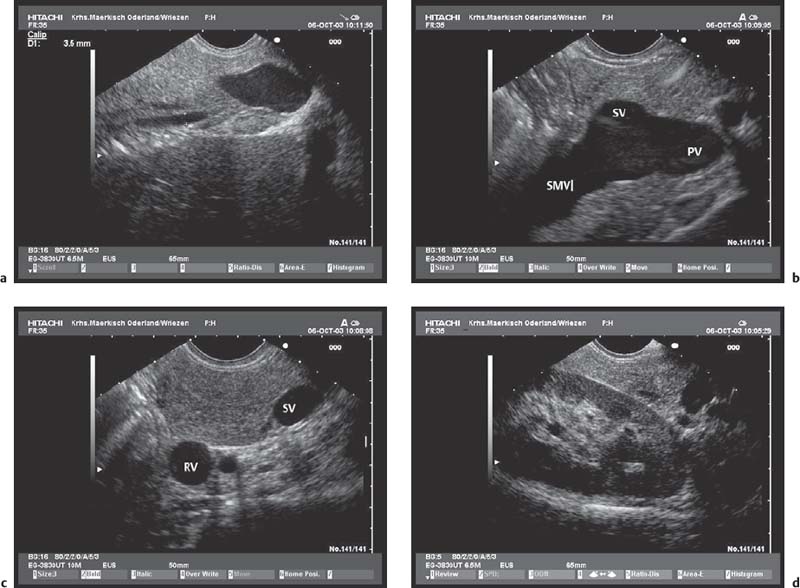

Fig. 16.1a–d The pancreas, viewed with a curvilinear-array echoendoscope.

a Seen from the gastric antrum, the confluence of the portal vein is a helpful anatomical landmark. The distal common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct are easily recognizable.

b The confluence of the portal vein and pancreatic neck. PV, portal vein; SMV, superior mesenteric vein; SV, splenic vein.

c View of the distal pancreatic body, seen from the gastric body. The splenic vein and splenic artery are anatomical landmarks. RV, left renal vein; SV, splenic vein.

d View of the pancreatic tail, adjacent to the left kidney, seen from the upper gastric body.

Characteristic | Normal appearance |

Size | Measurements as for abdominal ultrasonography and CT: • Pancreatic head: 25–30 mm • Pancreatic body: up to 20 mm • Pancreatic tail: 20–30 mm |

Contour | Smooth, fine, slightly hyperechoic outline of the pancreatic capsule. Variant: if the parenchyma is hyperechoic (“lipomatosis”), it is difficult to differentiate the pancreatic tissue from the peripancreatic fatty tissue |

Parenchyma | Medium echogenicity, regular lobulation by fine, hyperechoic internal echo reflexes (“pepper-and-salt” appearance) Variants: With increasing echogenicity of the parenchyma, the physiological heterogeneity of the parenchyma is lost and replaced by a more homogeneous appearance.41 The ventral part (embryological ventral anlage) of the pancreas can be differentiated as a variably well demarcated structure with lower echogenicity and variably regular lobulation |

Pancreatic duct | Anechoic smooth linear structure, sometimes slightly hyperechoic contour, width <2 mm (in the pancreatic body) |

Fig. 16.2a, b The embryological ventral part of the pancreas, viewed with a curvilinear-array echoendoscope.

a Viewed from the descending part of the duodenum, the pancreatic duct is seen.

b Viewed from the gastric antrum, the confluence of the portal vein can be used for orientation.

Fig. 16.3a–c Exclusion of pancreas divisum.

a, b Continuous visualization of the pancreatic duct from the ventral to the dorsal part of the pancreas.

c Pancreas divisum in a patient with recurrent acute pancreatitis: there is a separate orifice of the dorsal pancreatic duct at the minor papilla in pancreas divisum. Pancreas divisum can be confirmed and treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Endosonographic Criteria for Chronic Pancreatitis

The endosonographic criteria for chronic pancreatitis follow the ultrasound criteria, which were developed by Jones et al.13 and included in the Cambridge classification (see Table 16.1). The original 13 criteria developed in 1986 by Lees et al.21,22 were revised and modified by Wiersema et al. in 1993.50 In 30 patients in whom chronic pancreatitis had been confirmed by ERCP and/or an (intraductal) secretin test, calcifications and calculi in the pancreatic duct were found to have a positive predictive value of 100% for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis. From this study, the authors developed nine criteria, which now form the basis of most published studies on EUS in chronic pancreatitis. The five ductal criteria used by Wiersema et al. were dilation of the main pancreatic duct (MPD), calculi in the main pancreatic duct, dilated side branches, irregular ductal contour, and increased echogenicity of the main pancreatic duct wall; the four parenchymal criteria were hyperechoic foci, lobular pattern, focal hypoechoic areas, and parenchymal cysts46,50 (Figs. 16.4, 16.5, 16.6, 16.7, 16.8, 16.9 and 16.10).

In their study of the different stages of chronic pancreatitis, Catalano et al.51 modified the criteria developed by Wiersema et al.50 slightly and added “inhomogeneous echo pattern” and “lobular outer gland margin,” so that their classification included 11 criteria (the Milwaukee classification, with five ductal and six parenchymal criteria).51

There are a wide variety of views in the literature regarding the threshold number of criteria (within a range of one to five) required to diagnose chronic pancreatitis.51–63 Some authors have suggested that a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis can already be made if only one pathological feature is present, along with an appropriate clinical history.51,53 Other groups have obtained high negative and positive predictive values for EUS if the threshold for “normal” was set at a maximum of two pathological criteria, and if at least five of nine pathological criteria have to be fulfilled to establish a diagnosis of “abnormal.”9,52,58

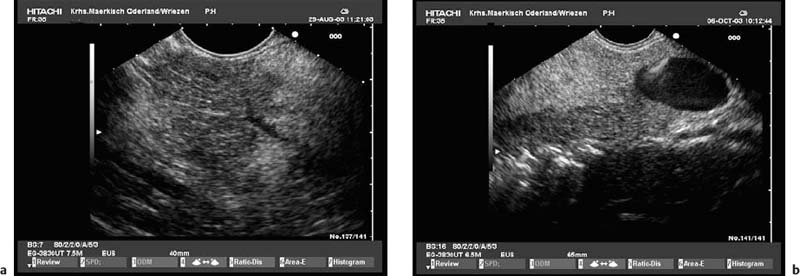

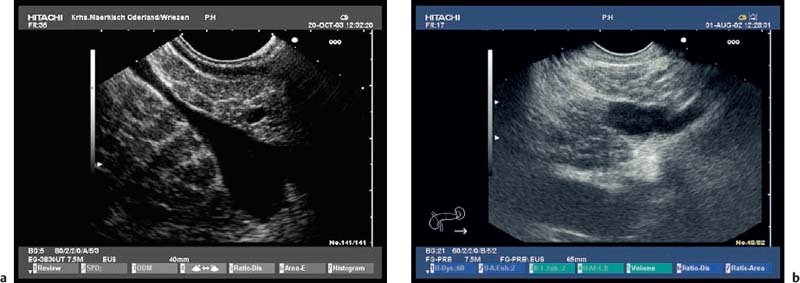

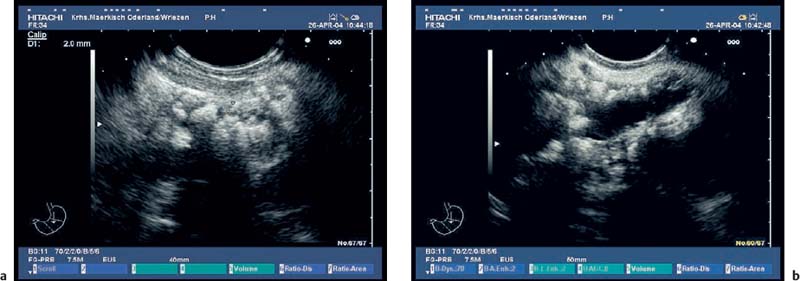

Fig. 16.4a, b Parenchymal criteria: inhomogeneities of pancreatic head (a) and body (b) caused by echogenic stranding, echogenicfoci (with and without shadowing).

Fig. 16.5a, b Parenchymal criteria: lobularity with honeycombing; increased echogenicity and slight irregularity in the pancreatic capsule.

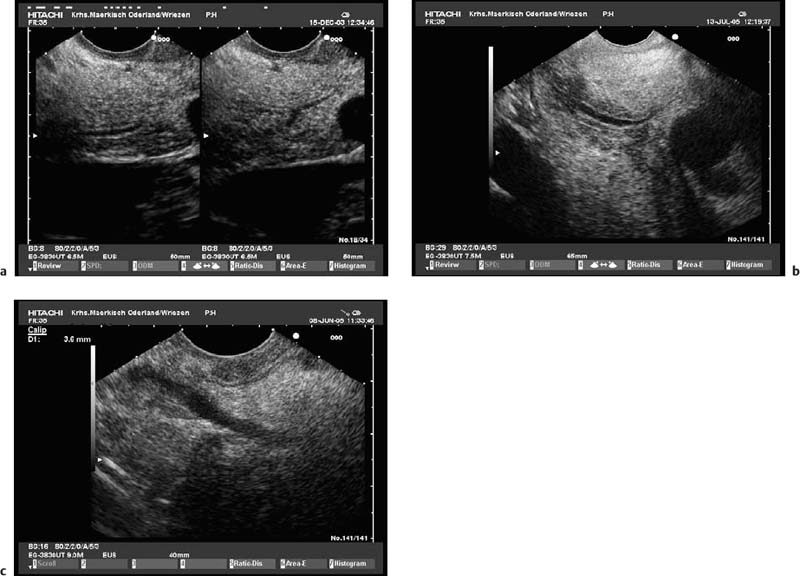

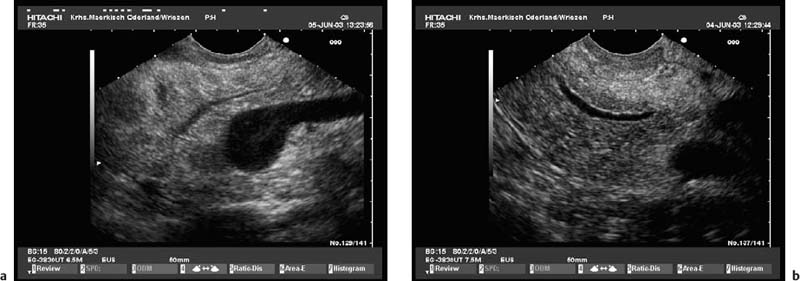

Fig. 16.6a, b Ductal criteria: hyperechoic and irregular main pancreatic duct (PD) contour in the pancreatic head and body (a, b); slight dilation of the PD in the pancreatic body.

Fig. 16.7a, b Typical endosonographic appearance of chronic pancreatitis. Moderatedilation and irregular, hyperechoiccontour of the main pancreatic duct (PD), inhomogeneous parenchyma with lobularity and stranding in the pancreatic head and neck (a); marked dilation, hyperechogenicity and irregular contour of the PD and of side branches in the pancreatic tail (b).

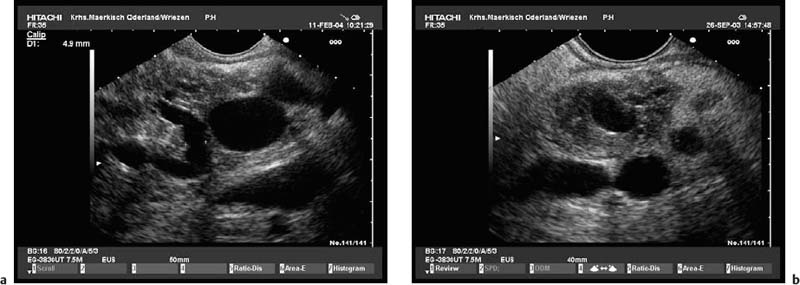

Fig. 16.8a, b Chronic pancreatitis with a small pseudocyst, which is partially filled with detritus.

a Very inhomogeneous parenchyma.

b Color power angio (CPA) mode. There is hyperperfusion around the margin of the pseudocyst.

Fig. 16.9a, b Hyperechoic reflexes with shadowing can be differentiated into pancreatic stones (a) or parenchymal calcifications (b).

Fig. 16.10a, b Advanced chronic pancreatitis with calcifications, marked parenchymal atrophy, pancreatic stones (a), and marked dilation of the distal pancreatic duct (b).

There are several further problems with using a threshold number of criteria for the EUS diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.9,40,52 Firstly, there are no consistent definitions of the various EUS features of chronic pancreatitis. Secondly, some features may be of much lesser diagnostic value if they are observed only in the relatively hypoechoic ventral pancreas and not in the body and the tail of the pancreas. Thirdly, some of the criteria used in various studies are related to each other—for example, ductal dilation and parenchymal atrophy (Fig. 16.10); echogenic stranding and honeycombing (see Figs. 16.4 and 16.5); hypoechoic parenchyma and increased echogenicity in the duct wall (see Figs. 16.6b and 16.7b). However, in cases of extreme ductal ectasia and parenchymal atrophy, it is possible that some parenchymal criteria, such as echogenic foci and stranding, may not be visualized (Fig. 16.10). In such cases, the required threshold number of criteria may not be met, although the picture would clearly be that of advanced chronic pancreatitis. In other cases, a marked honeycomb pattern in the absence of ductal ectasia may make it difficult to recognize subtle ductal changes. All studies are in agreement that echogenic foci with shadowing (parenchymal calcifications) and ductal calculi provide the highest diagnostic power.9,50–52 Further predictors of a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis are the number of endosonographic parenchymal criteria and a clinical history of alcohol abuse.52 So far, there have been no studies of the validity of the above criteria in larger groups of patients, and the criteria have only recently been correlated with clinical data such as age, sex, history of alcohol abuse, smoking, and clinical symptoms.43,54–57

Observer agreement between experienced examiners in making a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is moderate, both for radial systems64,65 and for curvilinear EUS systems.64 It is similar to the level of agreement in classifying hemorrhagic gastric ulcers using the Forrest classification. Only one study determined the agreement between radial and curvilinear systems and found it to be moderate.64 To achieve sufficient competence in interpreting endosonographic findings in suspected chronic pancreatitis, in comparison with the consensus of a panel of experts, it has been suggested that it is necessary to undergo a supervised training program consisting of 15–40 examinations of patients with chronic pancreatitis.66

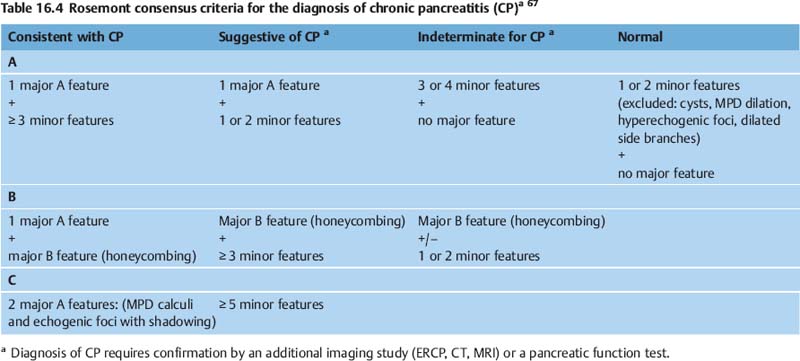

In an attempt to conclude controversies regarding the definition and threshold number of criteria, a group of experts in endosonography recently held a consensus meeting to define minor and major criteria (Table 16.3) and create a new EUS classification of chronic pancreatitis (Table 16.4).67 After an extensive review of the literature, including thorough discussion of the definitions of each EUS feature, the 32 experts who took part in the Rosemont consensus meeting achieved a good level of interobserver reliability(K >0.7) for each feature.67

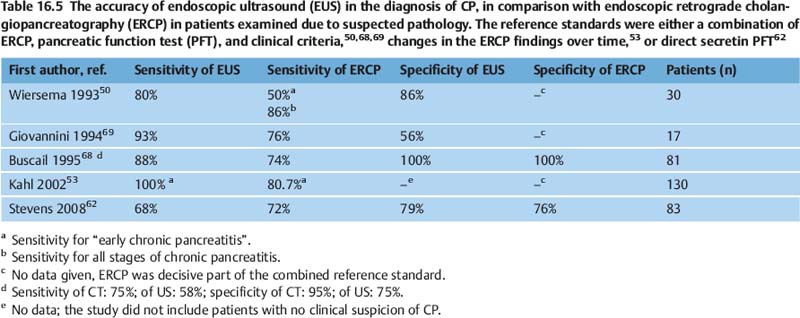

Comparison of Methods: Is EUS More Sensitive than ERCP for Diagnosing Chronic Pancreatitis?

On the basis of the criteria discussed in the previous section, the sensitivity of EUS for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis is at least as good as that of ERCP, which is commonly regarded as the morphological reference standard, and it appears to be superior to that of other imaging methods (US, CT, MRI/MRCP) (Table 16.5).7,50,53,59,60,62,68,69 However, more detailed comparison is difficult, for several reasons. Firstly, many of the endosonographic studies investigated highly selected patients, who were frequently suffering from severe chronic pancreatitis. Secondly, the diagnostic reference standard used differs between studies, with diagnostic methods used including ERCP,52,53,70–72 indirect pancreatic function test (PFT),70 a combination of ERCP and the secretin test,51 direct PFTs alone 58,62,63,80 or a combination of different tests together with clinical criteria.50,60,61,68 However, it is well known that only a small proportion of patients with slightly abnormal findings on ERCP (Cambridge categories 1 and 2) meet any of the clinical criteria for chronic pancreatitis.4 Four studies related endosonographic findings to the histology of resected pancreatic tissue, but did not compare EUS with other imaging techniques or PFT.73–76 Other studies tried to relate the endosonographic diagnosis to cytological or histological findings obtained with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA)70,77,78 or Tru-Cut biopsy (EUS-TCB).78,79

Parenchymal features |

Hyperechoic foci with shadowing (≥ 2 mm)a |

Lobularity (well-circumscribed, ≥ 5 mm structures with hyperechoic rim and relatively hypoechogenic center within the body and tail of pancreas) with honeycombing (≥ 3 contiguous lobules)b |

Lobularity without honeycombing (≥ 3 noncontiguous lobules)c |

Hyperechoic foci without shadowing (≥3; ≥ 2 mm) |

Cysts (anechoic, round/elliptic, ≥ 2 mm in short axis)c |

Stranding (≥ 3 hyperechoic lines, ≥ 3 mm in at least two different directions with respect to the imaged plane, not restricted to the ventral anlage)c |

Ductal features |

Main pancreatic duct (MPD) calculi (echogenic structures within the MPD with acoustic shadowing)a |

Irregular MPD contour (body and tail)c |

Dilated side branches (≥ 3; width ≥ 1 mm; body and tail)c |

MPD dilation (≥3.5 mm body; ≥1.5 mm tail)c |

Hyperechoic MPD margin (> 50% of MPD in body and tail, both borderlines of MPD)c |

Several studies have shown that, in patients who meet the ERCP criteria for chronic pancreatitis (Cambridge classes 2–4), a mean of 4.452 or a median of six (range three to seven) out of nine53 EUS criteria for chronic pancreatitis were present in the endosonographic examination.

Some studies have shown that, in patients with clinically suspected chronic pancreatitis, endosonography was able to identify changes consistent with this diagnosis, even though ERCP or CT did not show any signs of chronic pancreatitis.50–53,59,71,72 For example, in a study of 43 patients with clinically suspected chronic pancreatitis, Nattermann et al.71,72 found endosonographic criteria for chronic pancreatitis in 27 patients who had no changes in the pancreatic duct on ERCP. The combined results of the studies by Catalano et al.,51 Sahai et al.,52 and Wiersema et al.50 show that 25% of patients with clinically suspected chronic pancreatitis and normal ERCP had abnormal findings on EUS. Similarly, 40% of patients with clinically suspected chronic pancreatitis and normal pancreatic function tests were found to have abnormalities on EUS.4 In the study by Sahai et al., the 30 patients in whom ERCP did not support the clinically suspected diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis had a mean of 3.2 criteria of chronic pancreatitis on endosonography.52 The most commonly observed endosonographic findings in patients with clinically suspected chronic pancreatitis but normal ductography (on ERCP) were parenchymal inhomogeneities (lobularity, honeycomb pattern), increased echogenicity of the MPD wall, and changes in the contour of the pancreas. However, since the above studies used a cross-sectional design with no follow-up, the significance of abnormal endosonographic findings in patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis but normal ERCP findings and/or PFT remains controversial. There is still uncertainty regarding whether EUS can be used reliably to diagnose early chronic pancreatitis.4,9,40,46,54,74,80 This is partly due to the fact that some of the ultrasound and endosonographic criteria for chronic pancreatitis may also be present in asymptomatic individuals with no clinical symptoms of pancreatic disease, either with or without a history of alcohol abuse.43,54–57,82 However, the significance of abnormal findings on EUS in the presence of a normal ERCP may be different in symptomatic patients who have a history of alcohol abuse. In a region with a high prevalence of chronic pancreatitis, Kahl et al. studied a group of 38 patients with a history of chronic alcohol abuse and recurring upper abdominal pain who had at least one (median two) of the endosonographic (parenchymal) changes of chronic pancreatitis, but whose initial ERCP showed no ductal changes. After a median follow-up of 18 months, 22 of the patients (68.8%) developed changes typical of chronic pancreatitis on ERCP. The authors concluded that EUS may be more sensitive than ERCP for diagnosing early chronic pancreatitis, but that the endosonographic findings have to be interpreted against the background of the clinical history.53 Very similar conclusions were drawn from the clinical and CT follow-up of a small group of 16 patients in whom there was a strong clinical suspicion of chronic pancreatitis and in whom CT, MRI, or ERCP had initially been nondiagnostic. EUS correctly diagnosed chronic pancreatitis in 13 patients and in a further two patients yielded alternative diagnoses (autoimmune pancreatitis and MPD stricture of uncertain origin).59 Another study reported that in a cohort of 127 patients with dyspepsia but no clinical markers of pancreatic disease, approximately half met at least four of the pathological endosonographic criteria for chronic pancreatitis.1 On the other hand, there are conflicting results with direct PFT and EUS in the investigation of patients with suspected minimal changes in chronic pancreatitis.58,62,63,80 In view of the conflicting data and conclusions of the above studies, it is difficult to interpret the significance of such findings as long as no follow-up data for this population are available. It has been proposed that in diagnostically uncertain cases (endosonographic parenchymal criteria met, but normal ERCP; suspicion of autoimmune pancreatitis), cytological or histological examination using EUS-FNA70,78,81 or EUS-TCB78,83 may be helpful. However, since pancreatic EUS-guided biopsy carries a considerable risk, especially in patients with a history of pancreatitis,84,85 EUS-FNA in particular has a limited diagnostic yield,77,78,86 and a definite cytological or histological diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis may only have a limited influence on the clinical management, the diagnostic value of EUS-FNA and EUS-TCB remains to be determined.

In summary, then, the studies currently available suggest that EUS is at least as sensitive as ERCP in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and that it should be the diagnostic imaging method of first choice. However, the normal appearance of the pancreas may be very variable, particularly in elderly patients. In addition, it may be difficult or impossible to differentiate between residual changes of acute pancreatitis, alcohol-induced toxic fibrosis of the pancreas, and chronic pancreatitis. As is also true for ERCP and pancreatic function tests, the specificity of EUS is highly dependent on the patient group studied, or, in individual cases, on the clinical setting. If the clinical findings and the patient’s history are not taken into account, there may be a risk of overdiagnosing chronic pancreatitis when using EUS.1,4,87,88

A definite diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis can be made if the criteria of the Rosemont classification67 are met. However, in patients younger than 60 without significant regular alcohol consumption, the detection of only three or more endosonographic criteria is highly predictive of chronic pancreatitis.54,57 In such cases, further investigation is not required, and ERCP is only indicated for therapeutic interventions. Conversely, advanced chronic pancreatitis can be excluded if EUS only shows up to two minor pathological findings. ERCP, PFT, or other complex investigations for diagnosing chronic pancreatitis will probably be unhelpful and are not required. If the clinical presentation strongly suggests the presence of chronic pancreatitis (typical abdominal pain, chronic alcohol abuse), the presence of a limited number of endosonographic criteria is already suggestive for diagnosing early chronic pancreatitis. In such cases, in which EUS is suggestive of or only indeterminate for chronic pancreatitis, additional noninvasive imaging (especially MRI with MRCP),60 direct PFT, 58,62,63,80 or measurement of interleukin-8 in pancreatic juice at the time of EUS,61 or ERCP in selected cases, may be necessary in order to establish a definitive diagnosis.67 EUS-guided biopsy may be helpful to prove an alternative diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis.78,79 Long-term follow-up studies including symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with abnormal findings on EUS, but with normal ERCP and PFT, are needed.

If EUS is performed only shortly after an episode of acute pancreatitis—i.e., within 4weeks of it—it is not possible to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis reliably.88

Since the difference between acute recurrent pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis is the progression of morphological and functional changes over time in chronic pancreatitis, the diagnosis may be more easily made by repeated endosonographic follow-up examinations than by more invasive tests.

Pitfalls

• Anatomic variants. A ventral anlage is recognized in up to three-quarters of endosonographic examinations. In comparison with the dorsal pancreas, the ventral pancreas tends to show lower echogenicity and a more inhomogeneous structure. It is possible to misinterpret this hypoechoic ventral pancreas as a tumor or as focal chronic pancreatitis.9,44,46 In our experience, this is a common mistake in less experienced examiners.

• It may be difficult to differentiate the pancreas from visceral fatty tissue in patients with marked abdominal obesity (large amounts of visceral fat) who also have marked fatty changes in the pancreas.9,41,42

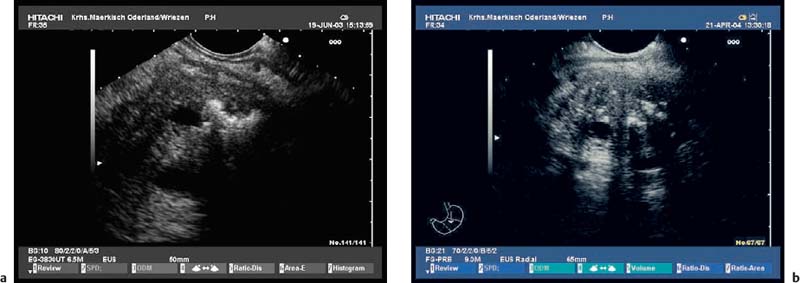

• Age-related changes in the pancreatic echo texture can be extremelyvariable. The pancreaticduct may become slightly ectatic, the echogenicity of the parenchyma and of the contours of the capsule and the ducts may increase, and the pancreas may develop an increasingly lobular structure. These changes cannot be differentiated from the changes in early chronic pancreatitis with certainty9,43,46,57 (Fig. 16.11).

• Structural changes in the pancreatic parenchyma that would be consistent with an endosonographic diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis may be present in asymptomatic patients with a history of alcohol abuse, in heavy smokers, and in patients with nonspecific dyspepsia. In such cases, a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis merely based on the EUS criteria may not necessarily be correct.1,46,54–56,87

• Hyperechogenic foci without shadowing, stranding, and a hyperechogenic or slightly irregular pancreatic duct wall are relatively nonspecific endosonographic findings, which may also be present in patients with no clinical markers of pancreatic disease. The duct wall is frequently hyperechoic in heavy smokers, and hyperechogenic foci are more common in men.82,87 These changes, as well as an increased lobular parenchymal pattern, may also be found in patients with chronicalcoholabuse who have a diffusely fibrosed pancreas but no chronic pancreatitis54–56,87 (Fig. 16.11a).

• Large calcifications and pancreatic calculi cause dorsal echo extinction and make it impossible to assess the pancreatic tissue situated dorsal to the calcification (Figs. 16.9 and 16.10a).

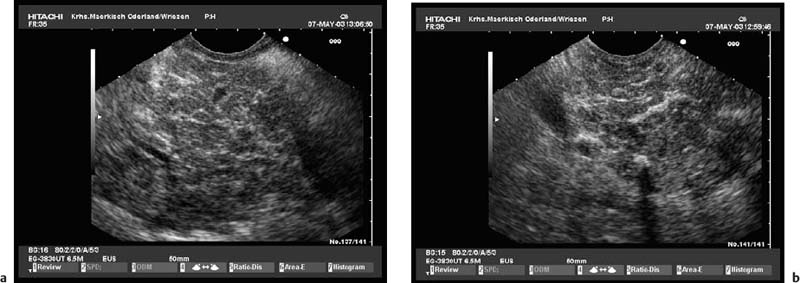

Fig. 16.11a, b Minimal changes in the echo texture of the pancreatic parenchyma.

a In a young patient with significant regular alcohol abuse.

b In an elderly woman with no clinical criteria for chronicpancreatitis.

Endosonographie Staging of Chronic Pancreatitis

EUS staging of chronic pancreatitis should follow the Cambridge classification.12 There are no internationally consistent EUS staging systems. Nattermann and Dancygier qualitatively correlated the ERCP grades in the Cambridge classification with endosonographic findings, indirectly weighting the findings into minor and major criteria.71,72 The endosonographic staging developed by Hollerbach et al. follows a similar principle.70 In contrast, Catalano et al.51 classified the presence of one or two of 11 endosonographic criteria as mild chronic pancreatitis (Cambridge category 2), the presence of three to five of 11 criteria as moderate chronic pancreatitis (Cambridge category 3), and the presence of more than five of 11 criteria as severe chronic pancreatitis (Cambridge category 4). We have suggested a staging system that accounts not only for the number of EUS features, but also takes into account the different weighting of these features.40 To make this compatible with the new Rosemont classification,67 we have modified our proposal as outlined in Table 16.6.

Cambridge class | Criteria |

Class 0 (no CP) | 0–2 features of the following: irregular MPD contour, hyperechoic MPD contour, lobularity without honeycombing, stranding |

Class 1 (uncertain)a | ≥ 1 feature of the following: cysts < 10 mm, dilation of MPD, hyperechogenic foci without shadowing, ≥ 3 side branches, lobularity with honeycombing, and ≥ 1 feature of the following: irregular MPD contour, hyperechoic MPD contour, lobularity without honeycombing, stranding or: 3–4 features of the following: irregular MPD contour, hyperechoic MPD contour, lobularity without honeycombing, stranding |

Class 2 (mild CP)a | At least 5 features including dilation of ≥3 side branches excluding dilation of MPD, hyperechogenic foci with shadowing (parenchymal calcifications), MPD calculi, and/or cysts >10mm |

Class 3 (moderate) | At least 5 features including obvious irregularities of the pancreatic duct (dilatation and/or variability of MPD, ≥ 3 dilated side branches) and lobularity with honeycombing excluding hyperechogenic foci with shadowing (parenchymal calcifications), MPD calculi and/or cysts > 10 mm, consistent with criteria of a typical pseudocyst |

Class 4 (severe) | At least 7 features including hyperechogenic foci with shadowing (parenchymal calcifications), MPD calculi and/or cysts > 10 mm, consistent with criteria of a typical pseudocyst |

Diagnosis of Complications of Chronic Pancreatitis

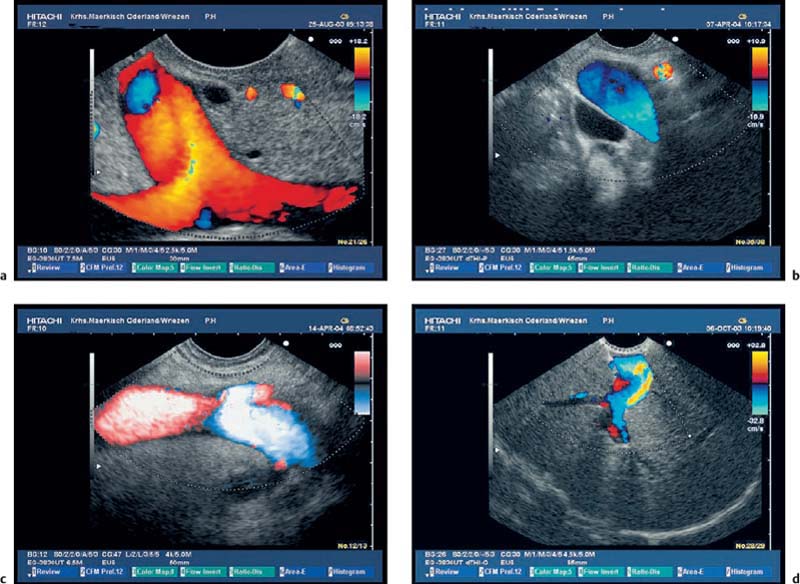

It is usually possible to diagnose the common sequelae of chronic pancreatitis or of acute recurrent pancreatitis, such as pancreatic pseudocysts, stenosis of the common bile duct, and portal or splenic vein thrombosis, using abdominal ultrasound or CT. Endosonography is therefore only rarely required.14,16–19 CCDS is more sensitive than CT for diagnosing vascular complications.15 However, if only abdominal ultrasound is used, it may still be difficult to demonstrate small pseudocysts or splenic vein thrombosis near the pancreatic tail, or, independently of the location, partial or locally restricted portal vein thrombosis. In patients in whom abdominal ultrasound is not diagnostic, endosonography with CCDS is often useful for showing thromboses and occlusions of the portal and splenic veins, as well as portosystemic shunts and gastric varices.89–92 Ultrasound contrast enhancement can be used to improve the reliability of EUS in diagnosing portal and splenic vein thromboses. In our experience, endoscopic ultrasound with systems capable of CCDS and color power angio (CPA)—electronic curvilinear and radial-array systems—can now be regarded as the most sensitive method of diagnosing vascular complications of chronic and acute pancreatitis (Figs. 16.12, 16.13, 16.14, 16.15, 16.16 and 16.17).

Fig. 16.12a–d Endosonographic imaging of the portosplenic vessels.

a The confluence of the portal vein.

b The portal vein in the portal region of the liver.

c The splenic vein within the pancreatic body.

d The splenic vessels in the hilar region of the spleen.

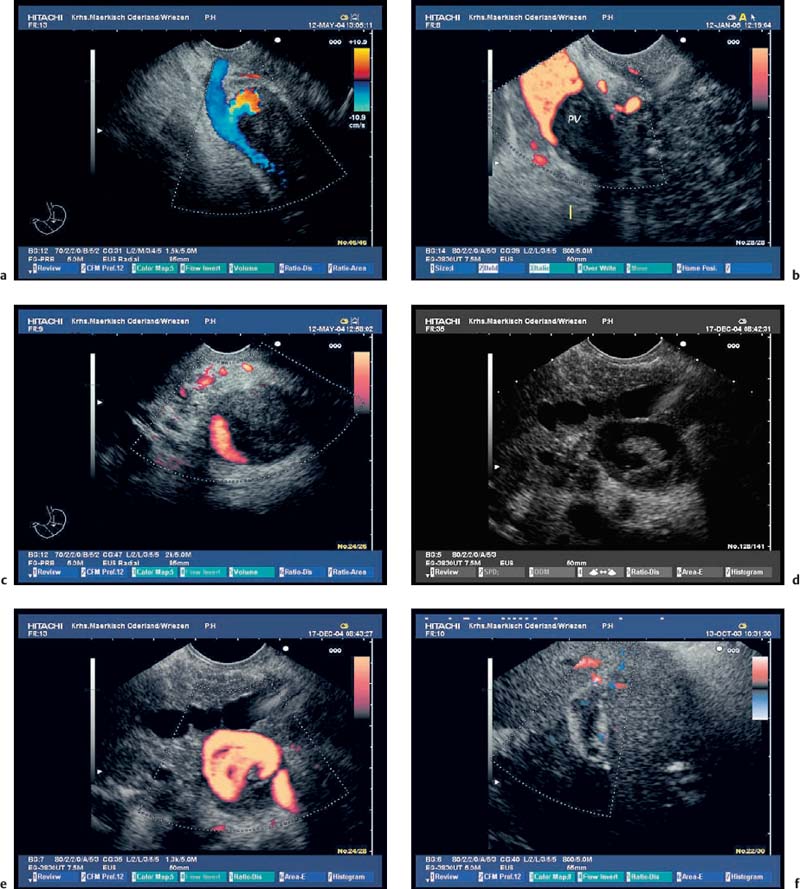

Fig. 16.13a–f Thrombosis of the portal vessels as a complication of chronic pancreatitis.

a, b Incomplete portal vein thrombosis with periduodenal collaterals. PV, portal vein.

c Dilated confluence of the portal vessels, with a large thrombus surrounded by some remaining blood flow.

d, e The confluence of the portal vessels with incomplete thrombosis; the dilation and irregular contour of the main pancreatic duct should be noted.

f Extension of a portal vein thrombus into an intrahepatic branch of the portal vein.

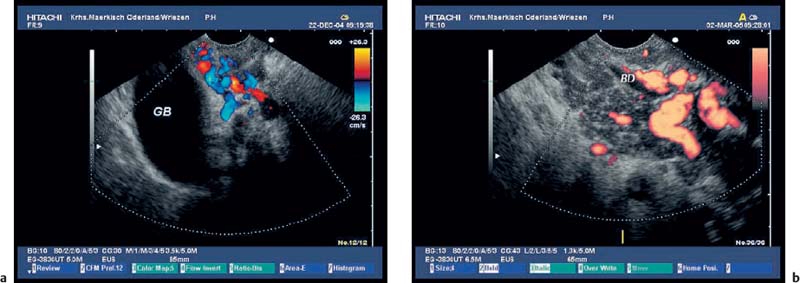

Fig. 16.14a, b Collaterals around the gallbladder (a) and around the common bile duct (b) in patients with chronic pancreatitis and thrombosis of the portal veins. BD, bile duct; GB, gallbladder.

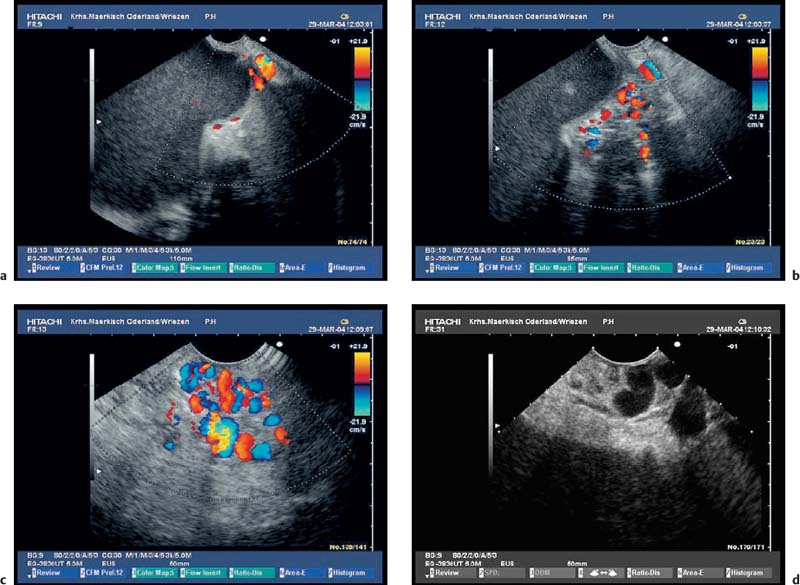

Fig. 16.15a–d a A space-occupying pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail.

b–d The lesion led to hilarsplenic vein thrombosis, with hepatopetal and hepatofugal collaterals, cavernous transformation of the splenic vein (b, c), and gastric fundic varices (d).

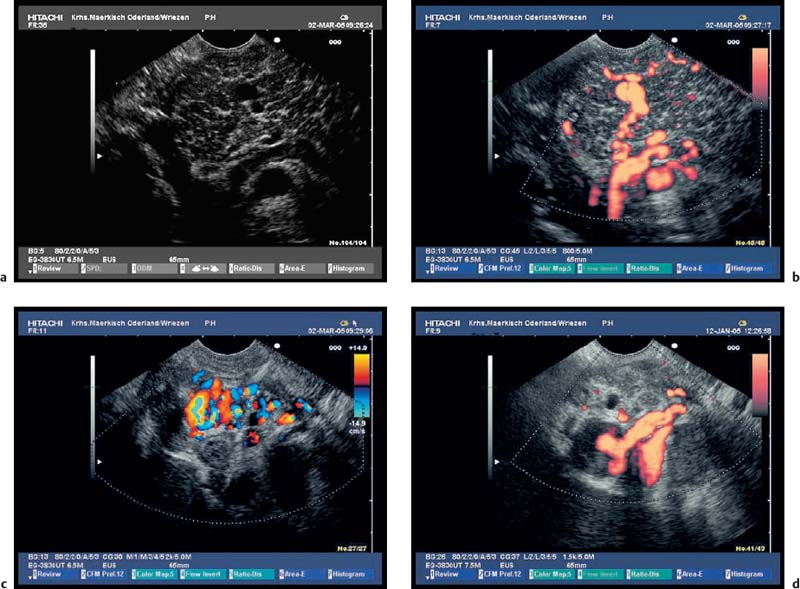

Fig. 16.16a–d Intrapancreatic hepatopetal collateralization in a patient with chronic pancreatitis and portosplenic thrombosis.

a Distinct parenchymal inhomogeneity in the pancreatic tail (echogenic foci without shadowing, stranding, lobularity with honeycombing, and also a suspicion of dilated side branches).

b Color power angio (CPA) mode reveals intrapancreatic collaterals, presumed to be dilated side branches.

c, d Color-coded duplex sonography (CCDS) also demonstrates peripancreatic collateral vessels (c)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree