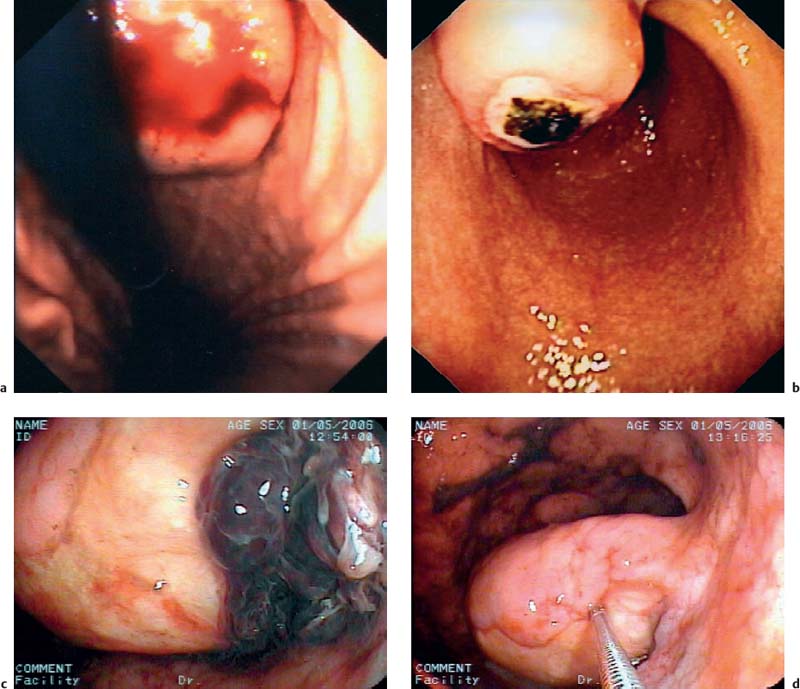

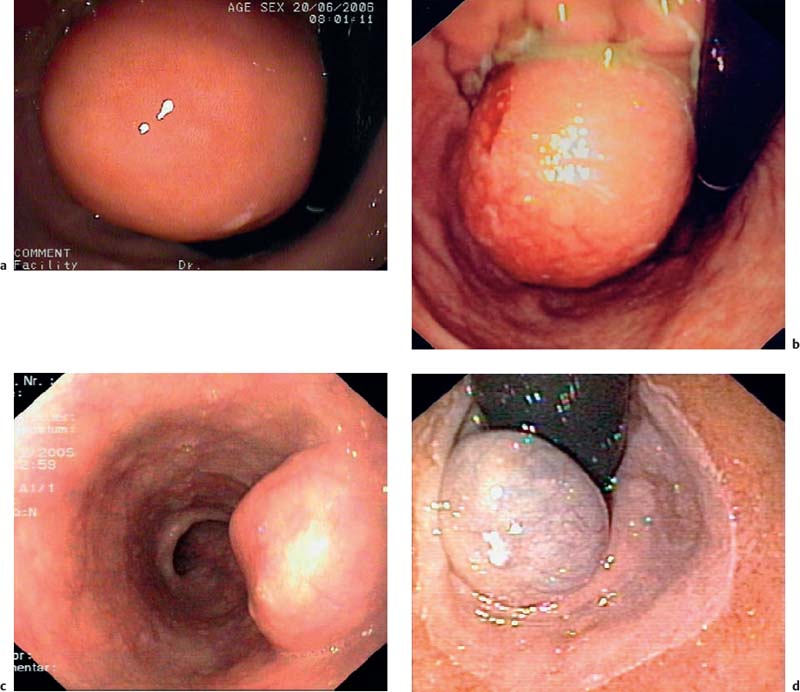

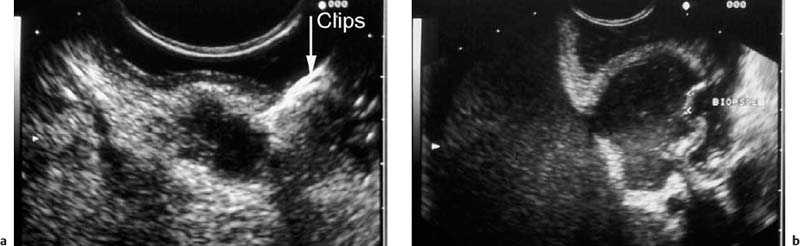

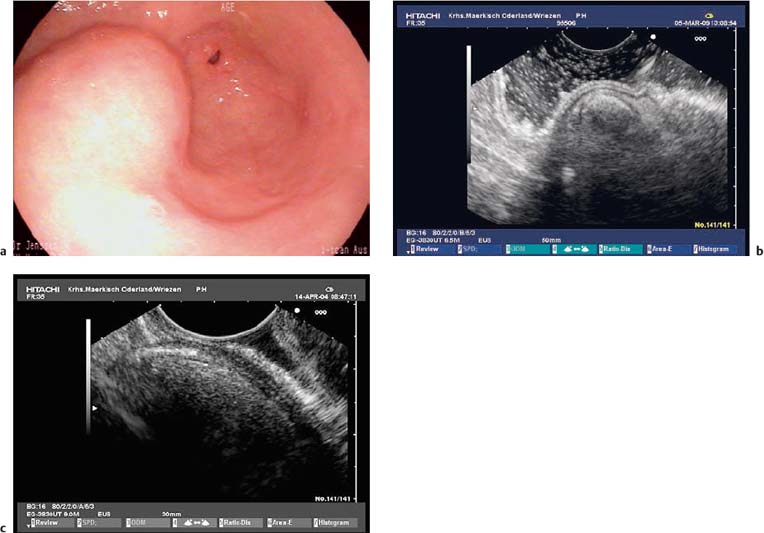

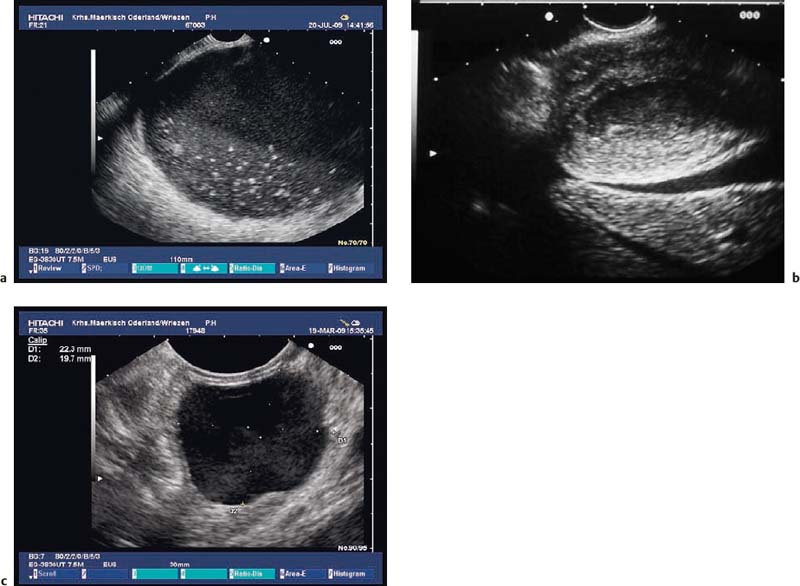

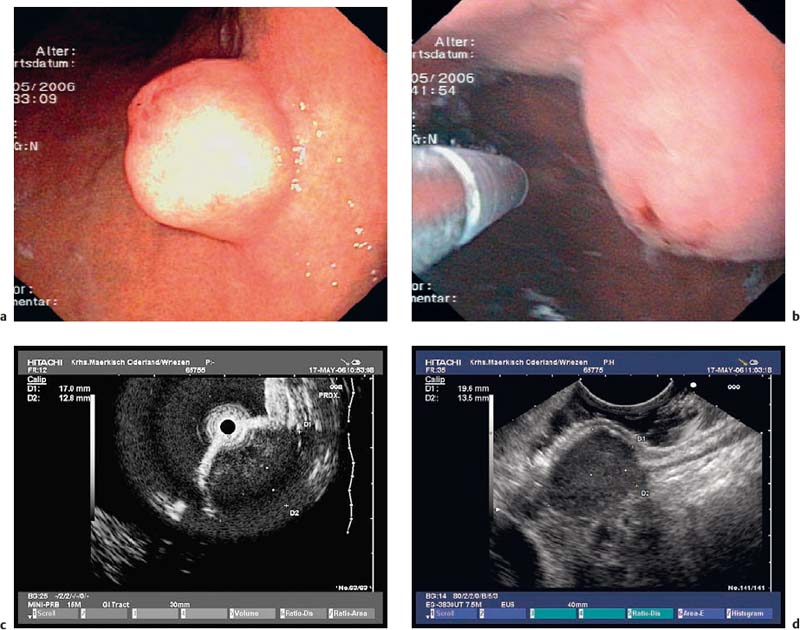

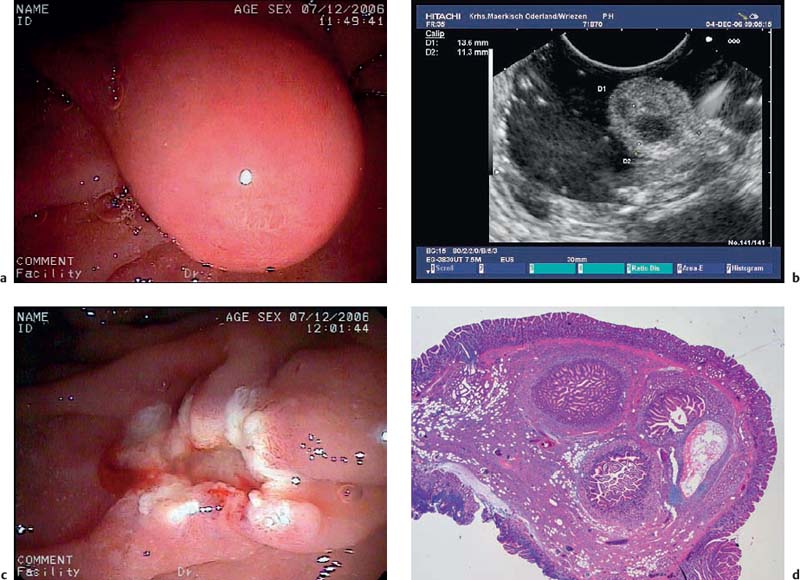

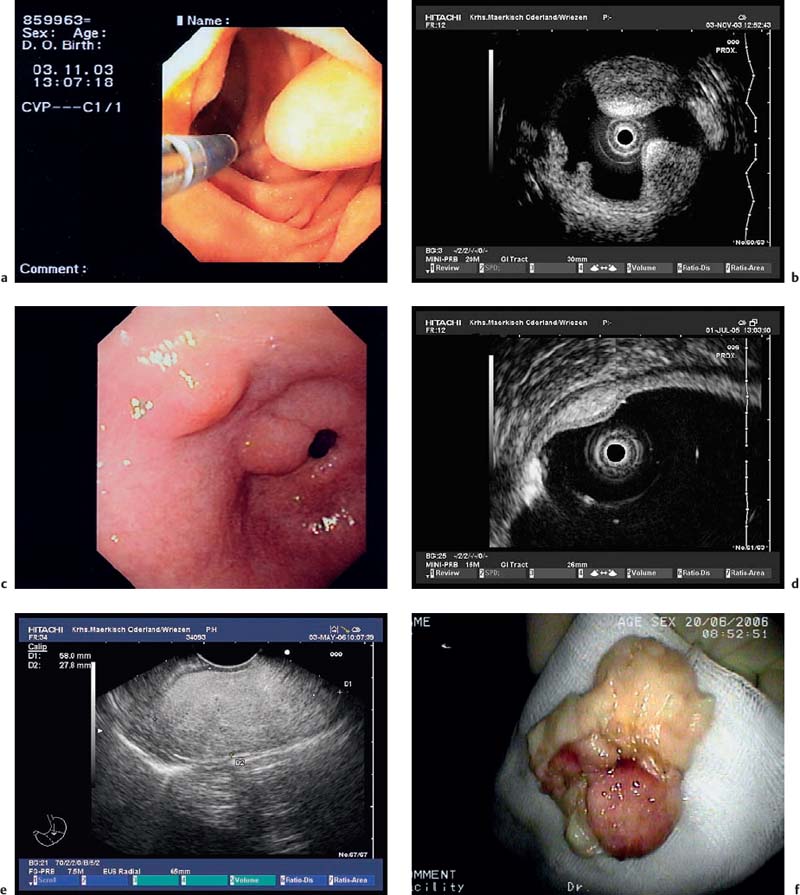

14 Endoscopic Ultrasound in Subepithelial Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract One of the classical indications for endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is the investigation of possible subepithelial tumors and the differential diagnosis, classification, and follow-up of these lesions.1–5 There are no reliable data on the incidence of subepithelial tumors and other submucosal lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, since in the majority of cases they remain asymptomatic and undiagnosed throughout life. Postmortem and surgical studies have found mesenchymal esophageal tumors (leiomyomas) in up to 8% of cases,6 and mesenchymal gastric tumors in half of all patients who died over the age of 50 years.5 In one study, “seedling” mesenchymal tumors (0.2–12.0 mm) were found in more than 50% of 150 esophagogastric resections for esophageal cancer or carcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (one or two small gastrointestinal stromal tumors in 10% of cases and 1–13 leiomyomas in 47% of cases).7 Certainly, small subepithelial tumors are diagnosed much less frequently in living patients. One older endoscopic study described subepithelial gastric tumors in only 54 of 15104 (0.36%) routine esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs).8 It can be assumed that with the increasing use of endoscopy and because of improved endoscopic imaging, they are now being discovered more often. One recent study in Asia found subepithelial tumors in 795 of 104159 upper gastrointestinal endoscopies (0.76%)9 and another in 188 of 5307 EGDs (3.5%).10 Subepithelial tumors were the third most common esophageal disease in 6683 EGDs performed for screening purposes in a Korean center (0.6%).11 Subepithelial tumors of the gastrointestinal tract are usually an incidental finding and may be entirely unrelated to the clinical question that prompted the endoscopic examination in the first place (Fig. 14.1).12–14 Over a period of 7 years, we carried out 346 endosonographic examinations for subepithelial lesions. In 87% of the examinations, the presenting symptoms did not correspond to the subepithelial lesion.15 Symptomatic subepithelial tumors present with overt or obscure gastrointestinal hemorrhage (Fig. 14.2), pain, abdominal discomfort, dysphagia, or symptoms of intestinal obstruction (Fig. 14.3).16–18,20 Fig. 14.1a–c Endoscopic view of small, asymptomatic gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors in the stomach (gastrointestinal stromal tumor, a), in the esophagus (granular cell tumor, b), and in the large intestine (leiomyoma, c). Fig. 14.2a–d Hemorrhage caused by subepithelial gastric tumors. a Overt bleeding (retrograde view). b Ulceration of a large gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with an adherent clot. c, d Avery large, ulcerated lipoma in the gastric body, causing severe gastrointestinal bleeding (c adherent clots; d extensive ulceration after removal of the clots). For the corresponding EUS image, see Fig. 14.27e. The distribution of subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract is not uniform. In endoscopic series reporting on subepithelial tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract, the stomach is the organ most frequently involved (in = 60–70% of cases); = 20–30% of subepithelial tumors are found in the esophagus, and fewer than 10% in the duodenum.12,18,19 The endoscopic findings may vary from subtle protrusions to tiny polyps or large, protruding mass lesions (Figs. 14.1, 14.2 and 14.3). As with radiographic methods, endoscopy is not capable of differentiating reliably between subepithelial tumors, intramural varices, and wall impressions caused by extraluminal lesions.1,3,14,21–27 In addition, it is not possible to diagnose the lesion type, the depth and extent of an intra mural lesion, or whether neighboring organs are involved.22,24,27 Endoscopic biopsy is usually unhelpful, as it only provides samples of the mucosa covering a subepithelial lesion, not tissue from the lesion itself. More invasive methods of tissue sampling, such as “buttonhole” or jumbo biopsies, have a low diagnostic yield and carry a high risk (Fig. 14.4).28–30 EUS is therefore an attractive noninvasive method in the investigation of subepithelial lesions of the gastrointestinal tract.15,18,31 Fig. 14.3a–d Endoscopic view of large subepithelial gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) causing symptoms. a, b Very large GISTs in the lesser curvature of the stomach (causing epigastric discomfort). c Amedium-sized subepithelial tumor in the esophagus (leiomyoma) in a patient with dysphagia. d A subepithelial tumor in the gastric cardia in an elderly patient with dysphagia and recurrent regurgitation (cavernous hemangioma; retrograde view). For the corresponding EUS image, see Fig. 14.20c, d. Fig. 14.4a, b Buttonhole biopsy of subepithelial gastric tumors. a EUS view of a subepithelial neuroendocrine tumor, with hemoclips in place after hemorrhage. b EUS view of agastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the stomach, showing a superficial defect after biopsy. Clinically, there was recurrent bleeding from the biopsy site.

| Chenetal. 200132 n = 238 (1993–2001) | Jenssen, Siebert (unpublished data, 2002–2007) n = 247 |

Patients with subepithelial tumors | 183 (76.9%) | 195 (79%) |

Patients with wall impressions caused by extraluminal structures | 55 (23.1%) | 52 (21%) |

Transient impression or not classified | 6(10.9%) | 8/52 (15.4%) |

Neighboring organs | 32 (58.2%) (10 spleen, 6 splenic vessels, 9 gallbladder, 3 liver, 3 pancreas, 1 intestine) | 30/52 (57.7%)(16 splenic vessels, 4 spleen, 4 aorta, 2 intestine, 1 pancreas, 2 liver, 1 uterus) |

Benign lesions | 12 (21.8%) (7 hepatic cysts, 2 hepatic hemangiomas, 1 splenic cyst, 2 pancreatic cysts) | 9/52 (17.3%)(3 pancreatic cysts, 3 cases of gallbladder pathology: cholecystitis, hydrops, concealed gallbladder perforation, 1 hematoma; 1 liver cyst, 1 splenic tumor) |

Malignant tumors | 5 (9.1%) (3 hepatic tumors, 1 pancreatic tumor, 1 splenic tumor) | 5/52 (9.6%)(2 pancreatic tumors, 1 splenic tumor, 1 liver tumor, 1 malignant lymphoma) |

Subepithelial Tumors versus Extramural Impressions (Lesions Mimicking Subepithelial Tumors)

Endoscopic ultrasound is a highly reliable method for differentiating between subepithelial lesions and wall impressions caused by extramural lesions.3,27,32–37 There is high interobserver agreement in the diagnosis of extramural lesions causing wall protrusion.38 In comparison with other methods such as barium contrast, endoscopy with biopsy, and computed tomography (CT), EUS shows considerable superiority in the diagnosis of such lesions, and should therefore be regarded as the investigation of first choice.21,23–25,39 There have been numerous studies reporting that among lesions endoscopically suspected to be subepithelial tumors, the proportion of extramural lesions causing wall impressions is in the range of 14–42%.24,32,33,40,41 In our own patients, we found extramural impression effects in 17.6% (74 of 420) of endosonographic examinations conducted for suspected subepithelial tumors.15 Extramural wall protrusions of this type are usually caused by neighboring structures such as the splenic artery, spleen, gallbladder, pancreas, liver, ovaries, uterus, or occasionally the intestine. More rarely, benign pathological changes in neighboring organs can cause wall impressions mimicking subepithelial tumors. In the upper gastrointestinal tract, such lesions may be cysts in the liver, pancreas, or spleen, mediastinal cysts, inflammatory lesions of the gallbladder or pancreas, benign tumors of the liver and spleen, adrenal gland adenomas, arteriovenous malformations, or arterial aneurysms. Only very rarely are external wall impressions caused by malignant tumors of the neighboring organs (e.g., carcinoma of the gallbladder, colon, pancreas, left adrenal gland, uterus or ovary, pleural, peritoneal and mediastinal malignancies, or lymphoma)5,23,26,32,33,42,43 (Table 14.1, Figs. 14.5, 14.6, 14.7 and 14.8).

Pitfalls

• High-frequency ultrasound miniprobes have a limited depth of penetration. They make it possible to exclude subepithelial tumors, but they are often insufficient to allow detailed imaging and diagnosis of extramural structures which cause external wall impressions (Fig. 14.9).

• When using a curvilinear echoendoscope, it is possible to mistake a hypertrophied pyloric sphincter for a subepithelial tumorin the fourth hypoechoic layer, especially if the hypertrophy is asymmetrical (Figs. 14.10 and 14.11).

• Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), especially in the stomach, may be connected to the fourth hypoechoic layer (tunica muscularis propria) only by a thin stalk, with the remainder of the tumor being located extraluminally (Fig. 14.12). Such tumors, especially epithelioid GISTs, are easily mistaken for a malignant lymph node, because their morphology and echogenicity may be very similar.44,45 If a fine-needle biopsy of such a tumor is carried out in the expectation of obtaining material from a suspicious lymph node, there is a danger that a GIST may be wrongly diagnosed as a metastasis from an epithelial malignancy.44

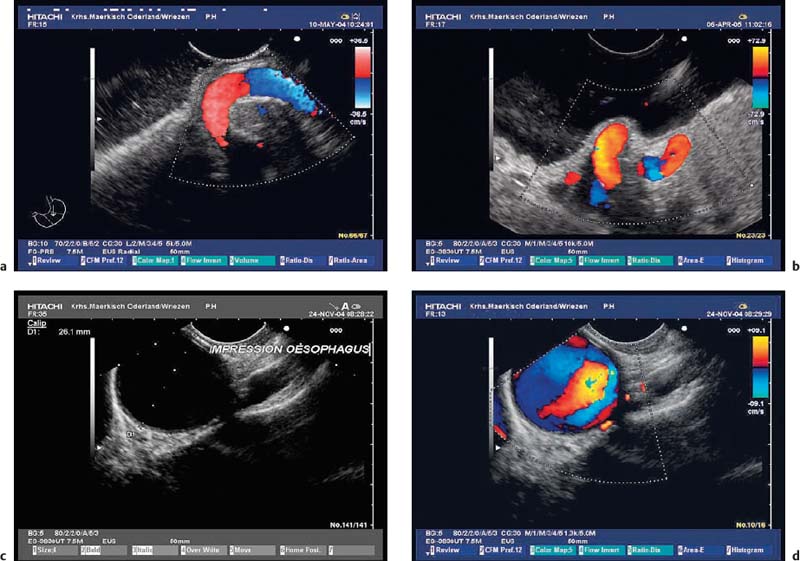

Fig. 14.5a–d Impressions on the gastric wall caused by adjacent vessels.

a, b Impressions on the gastric fundus made by elongated splenic arteries.

c, d An impression on the upper esophagus made by the aortic arch (c, gray-scale image; d, color-coded view).

Fig. 14.6a–c Impressions on the gastric wall caused by gallbladder pathology.

a, b Concealed gallbladder perforation (a endoscopic view, b EUS image).

c A sludge-filled gallbladder, with wall thickening and small calcifications (chronic cholecystitis).

Fig. 14.7a–c Impressions on the gastric wall caused by cystic mass lesions.

a An infected pancreatic pseudocyst.

b Liver abscess in a patient with an acute attack of chronic pancreatitis.

c A cyst in the left liver lobe.

Fig. 14.8a, b Impressions on the stomach wall (fundus) made by a tumor of the spleen (a) and a large carcinoma in the pancreatic tail (b).

Fig. 14.9a–d Amedium-sized gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) in the stomach.

a Endoscopic view.

b, c Attempted examination with a high-frequency ultrasound miniprobe. Delineation of the layer of origin turned out to be impossible due to the limited penetration depth.

d The longitudinal echoendoscope (7.5 MHz) makes it possible to detect the origin of the hypoechoic subepithelial tumor, in the fourth echolayer (muscularis propria).

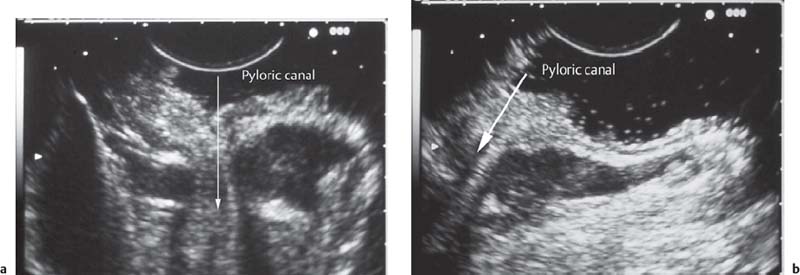

Fig. 14.10 Symmetric hypertrophy of the pyloric sphincter.

Fig. 14.11a, b Asymmetric hypertrophy of the pyloric sphincter (a, transverse view; b, longitudinal view).

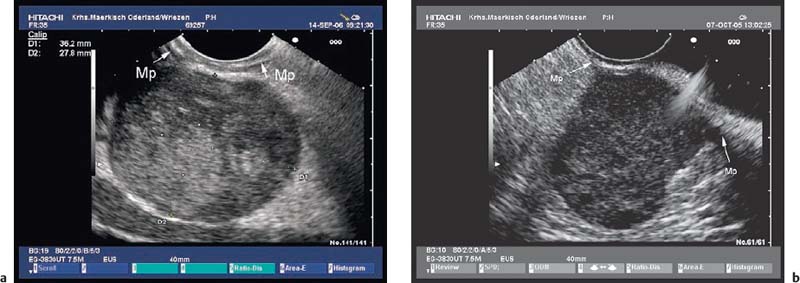

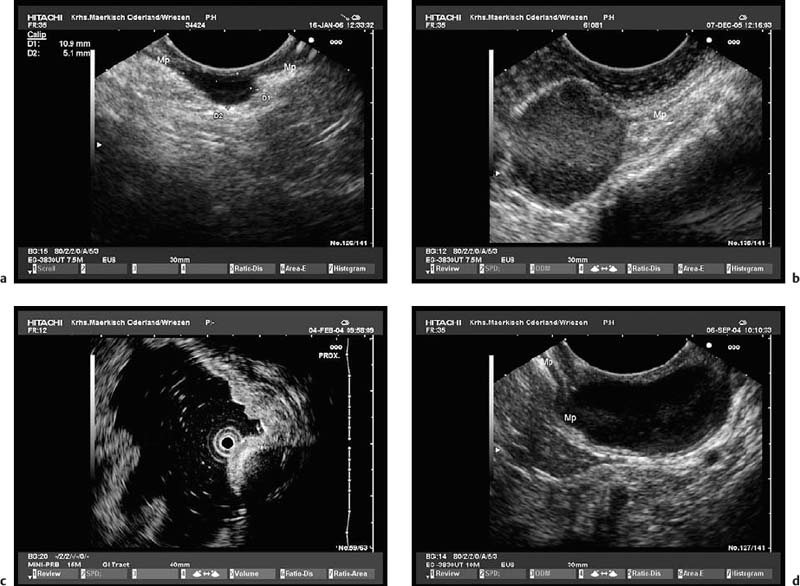

Fig. 14.12a, b Examples of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) in the stomach, with predominantly extraluminal growth. Mp, muscularis propria.

Endosonographic Description and Classification of Subepithelial Lesions

All of the echoendoscopes currently available (mechanical and electronic radial echoendoscopes, electronic curvilinear-array echoendoscopes), as well as high-frequency miniprobes, provide detailed views of the wall structure of gastrointestinal organs and make it possible to determine from which layer of the wall subepithelial lesions originate4,37,46,47 (Fig. 14.13). In addition, it is generally possible to measure the size of a lesion in two imaging planes. Two previous studies have demonstrated that EUS measures the subepithelial tumor size accurately in comparison with surgically resected specimens, with the exception of large lesions that extend beyond the sonographic penetration depth.25,48

Practical Hints

• Particularly important for follow-up studies: results obtained with radial scanning echoendoscopes (width and thickness) cannot be directly compared with measurements obtained with longitudinal scanning echoendoscopes (thickness and longitudinal diameter).

• High-frequency miniprobes are particularly useful in subepithelial lesions with a diameter of less than 20 mm, especially if an endoscopic therapeutic intervention is planned for the same session.46,47,49–51

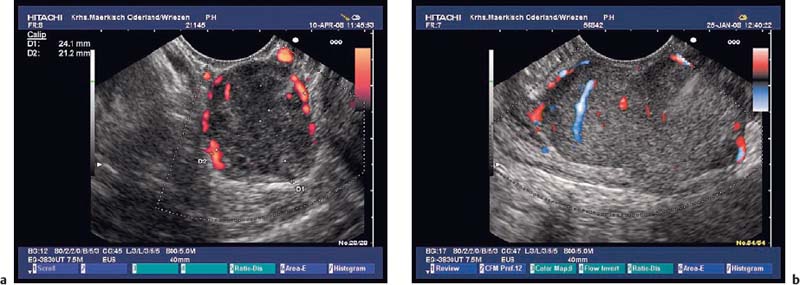

• In the investigation of subepithelial tumors, EUS not only provides B-mode views of the lesion. In addition, it is also possible to study the perfusion of a lesion using color-coded duplex sonography52 (Fig. 14.14) and to perform endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) (Fig. 14.15)18,19,54–75,206 as well as EUS-guided Tru-Cut biopsies (EUS-TCB).76–78 In addition, EUS-guided injection can be used to separate submucosal tumors from the muscular layer before endoscopic resection.81 In selected cases, EUS has been used to assist in the obliteration of subepithelial vascular malformations82 and for EUS-guided injection of ethanol or cyanoacry late for treatment of bleeding GISTs.83,84

• If the body of the stomach, the rectum, or the duodenum are being examined, we recommend filling the lumen of these organs in order to obtain adequate acoustic coupling. When the esophagus or gastric antrum are being examined, it may sometimes be helpful to use water-filled balloons.

• Good technique is essential to be able to measure the longitudinal extent of a tumor, to determine which mural layer it arises from, and to study its internal structure. Especially if a curvilinear-array echoendoscope is being used, one should remember to advance and retract slowly, to ensure optimal flexion of the tip of the endoscope, and to make certain that the endoscope attaches to the central longitudinal axis of the tumor.

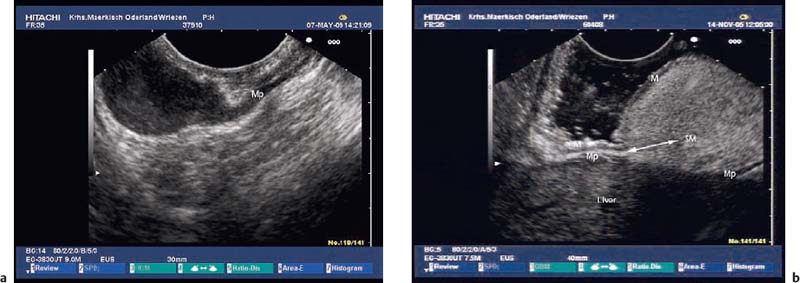

Fig. 14.13a, b Identifying the layer of origin of subepithelial tumors.

a A gastric leiomyoma, originating from the fourth hypoechoic sonolayer. Mp, muscularis propria.

b A large gastric lipoma, originating from the third hyperechoic sonolayer (submucosa) and covered by the second hypoechoic sonolayer (mucosa). M, mucosa; Mp, muscularis propria; SM, submucosa.

Fig. 14.14a, b Color-coded duplex sonography of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) in the stomach.

Fig. 14.15 EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of a hypoechoic subepithelial tumor (gastrointestinal stromal tumor) in the gastric body.

Endoscopic findings |

Localization |

Changes in the mucosa in the area of the protrusion (e.g., erythema, lymphangiectasia, erosions, ulceration, blood clots, active bleeding, color) • Sessile versus pedunculated • Additional findings: central nidus, consistency, mobility, pillow sign, tenting |

Endosonographic findings |

Diameter measured in two orthogonal planes |

Layer of origin (possible/not possible to determine; 2nd hypoechoic layer-3rd hyperechoic layer-4th hypoechoic layer; extramural) |

Margin (smooth/irregular) |

Can the lesion be distinguished from neighboring structures? (Yes/no; cannot be separated from…; clearly infiltrates…) |

Are the covering layers intact? (No mucosal defect; localized mucosal defect, mucosal and submucosal defect = ulceration; ulceration extending into the tumor) |

Solid; cystic; mixed solid and cystic |

Echogenicity (anechoic, hypoechoic, hyperechoic/mixed echogenicity) |

Texture (homogeneous, inhomogeneous—diffusely inhomogeneous versus inhomogeneous with defined internal structures) |

Defined internal structures: echogenic strains; echogenic spots (without echo extinction); calcification (echogenic reflexes with echo extinction); tubular structures; cystic structures: solitary/some/multiple |

Other findings |

If possible: show presence of blood vessels on color-coded duplex sonography (CCDS); estimate perfusion with color power angio (CPA) mode: no/some/multiple perfusion signals |

Suspicious-looking local or regional lymph nodes (morphology, location, number) |

Any hepatic lesions (in the parts of the liver that are visible): morphology, location, number |

Free fluid in the peritoneal cavity; pleural effusion |

Vascular |

Varices |

Vascular malformations and hemangiomas |

Cystic |

Simple cysts (solitary or multiple) |

Polycystic/septated cyst |

Mixed solid cystic lesions |

Solid |

Hyperechoic (homogeneous, heterogeneous, inhomogeneous) |

Hypoechoic (homogeneous, heterogeneous, inhomogeneous) |

Mixed echogenicity (heterogeneous) |

The endosonographic classification of subepithelial tumors is based on their outline, echogenicity, echohomogeneity, and internal echo pattern, as well as their demarcation from or infiltration of adjacent layers.15 Their echogenicity is compared with the muscularis propria (low echogenicity), the submucosal layer (high echogenicity), and to the lumen of the organ being examined, which should be filled with water or with water-filled balloons and there fore be anechoic.40,85 Some authors differentiate echogenicity in greater detail by also using the parenchyma of the spleen for comparison.86 Further criteria that can be used to classify subepithelial tumors are the extent of compressibility using the tip of the echoendoscope, the presence of ulceration, the presence of sonomorphologically abnormal or enlarged lymph-nodes, and the presence of a connection between the intramural lesion and extramural structures12,15,27,40,41 (Table 14.2).

Using electronic echoendoscopes with color-coded Doppler and color power angio functions makes it possible to assess the perfusion of subepithelial structures, which may sometimes simplify and accelerate the diagnostic process.52,53 As a modification of the classification used by Hizawa et al.,40 we suggest classifying subepithelial lesions according to the categories shown in Table 14.3.15

The criteria specified in Tables 14.2 and 14.3 should enable the examiner to determine the type of lesion and to judge whether or not the lesion may have malignant potential. In addition, the criteria should be helpful in deciding which further investigations and therapeutic options may be indicated. Numerous examiners have attempted to correlate the histopathological characteristics of subepithelial lesions with specific sonomorphological findings (Table 14.4).

Pitfalls

• The degree of “echogenicity” is a very subjective criterion in relation to stromal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. A study comparing the findings of five experienced endosonographers found very poor interobserver reproducibility, with a kappa value of 0.12.87

• In small lesions close to the transducer (e.g., in the esophagus), it is very difficult to differentiate between anechogenicity and low echogenicity. This can lead to diagnostic errors (e.g., cyst versus leiomyoma)88 (Fig. 14.16).

• The echogenicity of subepithelial tumors depends on their cellular density—the higher this is, the lower the echogenicity—and also on the number and size of internal structures such as cysts or blood vessels. Numerous small cystic changes or small blood vessels evoke numerous interface reflections and can cause a paradoxically high echogenicity.86,89,90

• Although no comparative studies have been published, the echogenicity of a lesion and its homogeneity appear to depend on the scanning frequency used, as well as on the various physical parameters and settings of the ultrasound system.

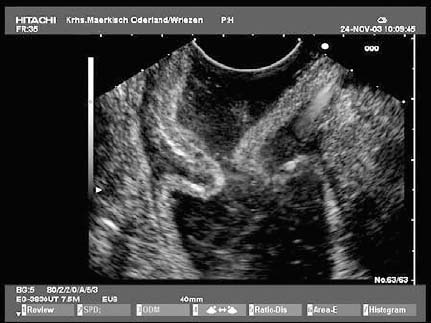

The diagnosis of vascular subepithelial lesions can usually also be made if color-coded Doppler sonography (CCDS) is not available.91 If the diagnosis has not already been made by conventional endoscopy, varices can easily be recognized by following their course, by their compressibility, and by demonstration of extramural collateral vessels. However, the diagnosis can be made more quickly using CCDS, and additional information can be obtained—for example, a portosplenic thrombosis may be recognized (Figs. 14.17, 14.18 and 14.19).

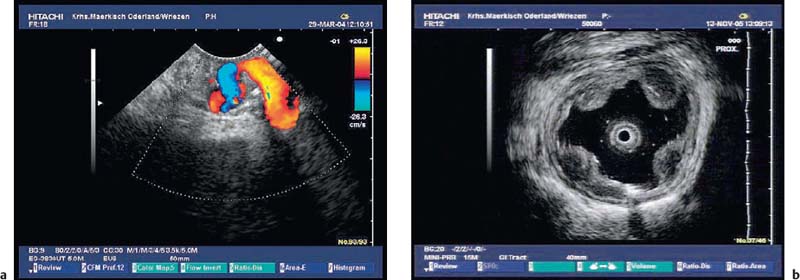

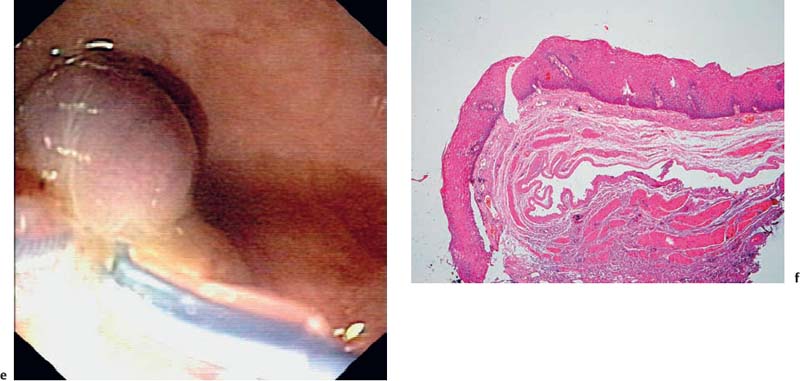

Intramural cavernous hemangiomas are very rare,92,93 but they can be diagnosed much more easily using CCDS (Fig. 14.20).

Fig. 14.16a, b It is difficult to distinguish between small, anechoic lesions and subepithelial tumors with low echogenicity. Are these cysts or solid, hypoechoic tumors in the gastric wall (a) or esophageal wall (b)?

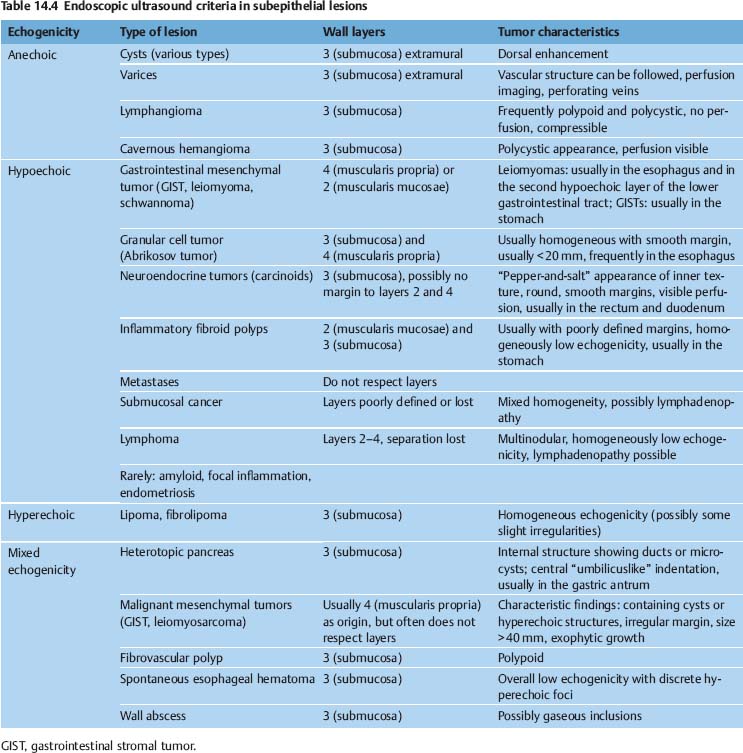

Fig. 14.17a, b Vascular subepithelial lesions: giant varices in the cardia.

Fig. 14.18a, b Vascular subepithelial lesions a Varices in the gastric body.

b Esophageal varices (15-MHz miniprobe).

Fig. 14.19a, b a Portal thrombosis (T) as a consequence of an acute attack of chronic pancreatitis. PD, dilated pancreatic duct.

b Bile duct varices as a consequence of portal thrombosis in a patient with acute pancreatitis. CBD, common bile duct.

Fig. 14.20a–f Cavernous hemangioma

a-c Acavernous hemangioma in the rectum (a, b) and gastric cardia (c, B-mode image).

d The afferent vessel, imaged using the color-power angio mode.

e Endolooping and endoscopic resection of the lesion.

f Histological image of the resected specimen (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 40). (Courtesy of S. Wagner, Konigswuster-hausen, Germany.)

Simple cystic | Duplication cysts |

Bronchogenic cysts | |

Heterotopic gastric mucosa | |

Rare: • Brunner gland hamartoma • Mucocele • Intramural pancreatic pseudocyst • Abscess of the stomach wall (low echogenicity) • Pancreatic heterotopia | |

Multicystic | Lymphangioma |

Heterotopic gastric mucosa and gastritis cystica profunda | |

Brunner gland hamartoma | |

Solid cystic | Pancreatic heterotopia |

Lymphangioma | |

Rare: • Tuberculoma • GIST with cystic degeneration |

Cystic and Mixed Solid Cystic Subepithelial Lesions

Cystic and Mixed Solid Cystic Subepithelial Lesions

Anechoic nonvascular subepithelial lesions account for a large variety of underlying diagnoses. They may represent different types of cysts (bronchogenic cysts, duplication cysts),55,94,95,103,104,106 mucosal heterotopia located in the submucosal layer,40,101,116 Brunner gland hamartomas,113–115 cystic lymphangiomas (lymphatic cysts),89,101,108,110 or more rarely pancreatic heterotopias,111 mesenchymal tumors with cystic degeneration,105,112 gastritis (colitis) cystica profunda,117–119 tuberculomas, mural abscesses or empyema,97–99,120–122 or mucoceles.100,109

This multitude of differential diagnoses makes it difficult to reach a confident diagnosis. To simplify the diagnostic process, the examiner should differentiate between simple cystic lesions, polycystic/septated lesions, and mixed solid cystic subepithelial lesions15,40,101 (Table 14.5).

Simple submucosal cysts have been found endosonographically in the esophagus, in the stomach, in the duodenum, and near the cecal pole.100–109 Simple submucosal cysts are round anechoic lesions with a smooth margin that can only be slightly compressed with the tip of the echoendoscope and which show dorsal enhancement. Occasionally, sedimented debris can be seen in the lumen of the cyst. Duplication cysts can usually be recognized through a duplicated wall, although this is not always visible. In appropriate cases, EUS-FNA can be helpful for further diagnostic and therapeutic management 5,37,55,94–96,103–106

Cystic and cavernous lymphangiomas are the most frequently encountered polycystic subepithelial lesions. They are usually found in the small and large intestine, more rarely in the stomach, and very rarely in the esophagus. They are benign lesions that consist of cavities or dilated lymphatic vessels situated in the submucosal or mucosal layers. Their inner wall is covered by an epithelial layer, and they are subdivided by irregular septal structures that consist of smooth muscle or connective tissue. Depending on their size and location, they may occasionally cause symptoms. Endoscopically, they usually appear as soft, broad-based polypoid structures, which are covered with normal or erythematous mucosa. They are easily compressible with forceps. In the duodenum and small intestine, it is often possible to find mucosal lymphangiectasia, evident from multiple dot-shaped whitish mucosal elevations. Somewhat more rarely, cystic lymphangiomas may have a pedicle.107 Endosonographically, lymphangiomas are usually found in the third hyperechoic layer, although sessile lesions in particular may extend to the second hypoechoic layer. The endosonographic picture may vary depending on the size and number of the dilated lymphatic vessels and depending on the extent to which bundles of smooth muscle and connective tissue subdivide the lesion. If the lymphangioma consists of moderately dilated tortuous lymphatic vessels, or if it contains small cysts, EUS will usually show multiple hypoechoic or anechoic structures, possibly with hyperechoic subdivisions. Such lymphangiomas may also appear as simple or septated round or oval anechoic lesions in the third hyperechoic layer (Fig. 14.21). However, if the lymphatic vessels are very small (diameter < 1 mm), the lymphangioma will appear as a slightly inhomogeneous submucosal tumor with medium echogenicity.89,101,107–110

Heterotopia of the gastric mucosa, submucosal hyperplasia of Brunner glands, submucosal hamartomas, enteral cysts. A very similar appearance with the same endosonographic localization in layers 2 and 3 can be found for the different types of subepithelial heterotopia of the gastric, duodenal, and enteral mucosa (Figs. 14.22 and 14.23).40,113–116 The range of endosonographic findings extends from simple submucosal cysts, which may also be multiple, through polycystic lesions with hyperechoic septa, to inhomogeneous hyperechoic submucosal tumors with small cystic areas. A special scenario is gastritis cystica profunda, which appears as a polycystic lesion and can often be found near the anastomosis after gastric surgery117,118 (Fig. 14.24).

Endoscopically, these lesions appear as broad-based or stalked polyps. Subepithelial heterotopia of the gastric mucosa in Japanese patients is frequently (19–100%) associated with gastric cancer, particularly if multiple lesions are present. Occasionally, the carcinoma may arise from the subepithelial heterotopia (Fig. 14.25).101,116–119,123,124

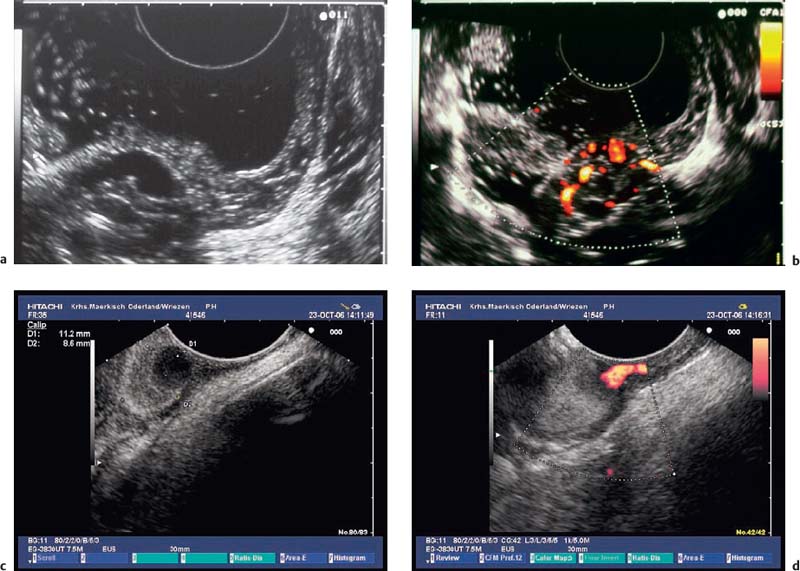

Heterotopic pancreatic tissue (aberrant or ectopic pancreas). A further differential diagnosis of mixed solid cystic, heterogeneous solid, and rarely of cystic subepithelial lesions is heterotopic pancreas, which is usually located in the stomach, or more rarely in the esophagus, the small intestine, the duodenum, the papilla, or in other organs. Its incidence in autopsy series varies between 0.6% and 13.7%.125 It is typically diagnosed incidentally during endoscopy, surgery, or postmortem examination. Rarely, it causes symptoms such as gastric outlet obstruction or intestinal obstruction, ulceration and bleeding, obstructive jaundice, ectopic pancreatitis, cystic dystrophy, and pseudocyst development.125–134 Adenocarcinoma, mucinous neoplasia, or neuroendocrine tumor arising within ectopic pancreas are very rare occurrences.135–140,281 The endosonographic appearance is determined by the histological type of the lesion.141,142 Type I heterotopia consists of complete pancreatic tissue (acini, ducts, Langerhans islets), type II of pancreatic tissue without any ducts, and type III of pancreatic ducts only. Heinrich type III ectopic pancreas is traditionally also known as adenomyoma.143 Type III pancreatic heterotopia as well as pancreatic heterotopia with pseudocyst may appear as a simple or septated anechoic lesion with smooth margins, which is located in the third echogenic layer.105,144 Heinrich types I and II pancreatic heterotopia appear as heterogeneous and hypoechoic subepithelial lesions with poorly defined margins, finely scattered hyperechoic spots, and occasionally calcifications, and in about one-third of cases with small cystic spaces and ductlike structures.40,101,141,142,145 The irregular margins are caused by lobulated acinar tissue, and the mixed echogenicity is due to ducts, small cysts, lobulated tissue, areas of fat, and bundles of muscle fibers.141 A characteristic feature of submucosal pancreatic heterotopia is a thickening of the fourth layer adjacent to the mass. In a series of 10 pancreatic heterotopias located in the stomach that were studied both endosonographically and histologically, five were only located in the third echogenic layer (submucosa) and were easily differentiated from the fourth layer (separate type, Fig. 14.26c, d, Fig. 14.50a). In the remaining five cases, the lesion extended into the third echogenic and fourth hypoechoic layer (fusion type, Fig. 14.26a, b).141 When the endoscopic findings (usually situated in the gastral antrum, central umbilication) are also taken into account, pancreatic heterotopia may be diagnosed endosonographically with a reasonable degree of certainty (Fig. 14.26b, Fig. 14.50b).142,146 In a study of six patients, an endosonographically suspected diagnosis of pancreatic heterotopia was confirmed histologically in all cases after endoscopic resection.88

Fig. 14.21 A submucosal lymphangioma in the esophagus.

Fig. 14.22a, b Submucosal cystic heterotopia in the gastric mucosa, situated in the gastric antrum. a Radial 15-MHz ultrasound miniprobe.

b Histological confirmation after endoscopic resection. (Histological image courtesy of S. Wagner and S. Bartho, Königswusterhausen, Germany).

Fig. 14.23a–d A subepithelial solid cystic lesion in the descending duodenum, near the papilla.

a Endoscopic image.

b EUS image.

c Endoscopic snare resection.

d Histological diagnosis of an enterogenic cyst (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification × 40). (Courtesy of S. Wagner, Konigswuster-hausen, Germany.)

Fig. 14.24 Gastritis cystica profunda close to the anastomosis after a Billroth II gastrectomy (with a mechanical radial echoendoscope). (Courtesy of M. Mayr, Berlin).

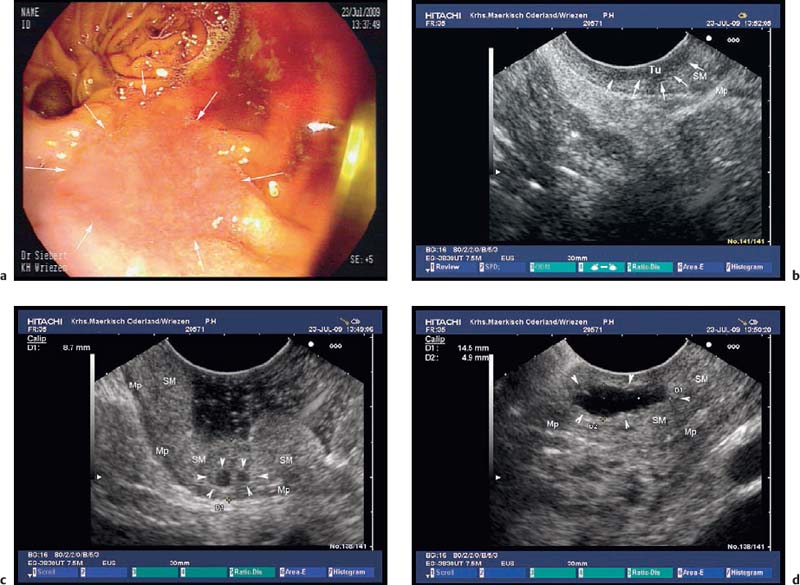

Fig. 14.25a–d Submucosal cysts in a patient presenting with cancer of the gastric remnant 20 years after partial gastric resection because of complicated ulcer disease.

a A flat-depressed lesion near the anastomosis (arrows): histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma.

b EUS image of the hypoechoic thickening of the mucosa, focally infiltrating the submucosal layer (arrows): stage T1a cancer. Mp, muscularis propria; SM, submucosa; Tu, tumor.

c, d EUS image of cysts (arrowheads) in the thickened submucosal layer of the gastric remnant. Mp, muscularis propria; SM, submucosa.

Fig. 14.26a–d Heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the stomach.

a The typical EUS features of the fusion type—i.e., with the muscular layer also affected, as confirmed histologically after surgical resection.

b-d The separate type—i. e., with only the submucosa affected.

b The endoscopic image, with central umbilication.

c The EUS appearance.

d Histological confirmation after endoscopic resection (histological image courtesy of S. Bartho and S. Wagner, Königswusterhausen, Germany).

Echogenic subepithelial tumors—lipomas, fibromas, and fibrovascular polyps. Lipomas are the most common echogenic subepithelial lesions. They usually appear as flat or sessile polypoid lesions, although they may have a stalk. They are classically located in the right colon, but can also appear in the stomach and duodenum. Frequently, an endosonographic examination is not required if the endoscopic findings are unequivocal (slightly yellow shimmering through the mucosa, pillow sign).12,27 Endosonographically, lipomas appear as intensely hyperechoic, entirely homogeneous well-demarcated lesions located in the third echogenic layer (submucosa). Some inhomogeneities can sometimes be seen, particularly if the tumor is large 12,23,25,27,36,37,40,109,147 (Fig. 14.27).

Interobserver agreement for diagnosing a lipoma is good.38 The differential diagnosis includes fibromas and, in the esophagus, fibrovascular polyps (fibrolipomas). The latter consist of a mixture of mesenchymal tissues and also contain fatty tissue. Only the lipomatous areas appear homogeneously echogenic, whereas the fibrous and muscular parts of these polyps show less echogenicity.148

In exceptional cases, inflammatory fibroid polyps (IFPs) may appear hyperechoic if numerous small blood vessels cause multiple interface reflections.86,149

Hypoechoic subepithelial tumors are a very heterogeneous group. In our own patients, 247 of 346 (71.4%) nonvascular subepithelial lesions showed low echogenicity.15 They present the examiner with several problems. The range of diagnoses includes benign tumors such as leiomyomas, glomus tumors, granular cell tumors, schwannomas, pancreatic heterotopias, and inflammatory fibroid polyps (IFPs), but also includes (potentially) malignant lesions such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), neuroendocrine tumors, leiomyosarcomas, malignant lymphoma (Fig. 14.28), and submucosal metastases.13 Very rarely, amyloidosis,150 endometriosis,63,109,151,152 cavernous hemangiomas,92,93 tuberculosis, inflammatory tumors, and abscesses98,99,122 (Fig. 14.29) may present as hypoechoic subepithelial lesions.

Fig. 14.27a–f Submucosal lipomas in the upper gastrointestinal tract.

a In the water-filled duodenal lumen, a radial 15-MHz ultrasound miniprobe has been introduced through the endoscope’s working channel.

b The corresponding EUS image (15-MHz miniprobe).

c, d Flat submucosal lipomas in the gastric antrum, with the endoscopic view (c) and corresponding EUS image (15-MHz miniprobe) (d).

e, f A huge lipoma in the gastric body, with the EUS image (e) and endoscopically resected tumor (f). For the corresponding endoscopic images, see Fig. 14.2c, d.

Fig. 14.28a, b Endosonographic images of a submucosal mantle cell lymphoma in the gastric body (images reproduced with permission from Jenssen and Dietrich15).

a Examination with the 15-MHz ultrasound miniprobe.

b With the longitudinal echoendoscope.

Fig. 14.29a, b Submucosal abscesses following acute episodes of chronic pancreatitis.

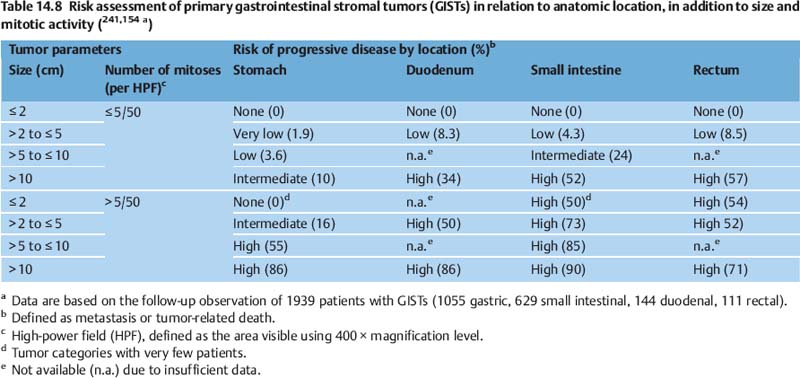

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) represent the largest group of mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and include tumors with a very variable clinicopathological spectrum and biological behavior. The most common locations are the stomach (60%), small bowel (30%), and duodenum (5%). Only small numbers of cases have been detected in the large bowel (< 5%), lower esophagus and appendix (<1%), and in the omentum, mesenteries, or retroperitoneum.153–155 In the early large endosonographic series,21,23,25,36,37,39 hypoechoic mesenchymal tumors arising from one of the two muscular layers and histologically showing either a spindle cell or an epithelioid structure were either classified as myogenic tumors (leiomyomas, leiomyoblastomas, and leiomyosarcomas) or neurogenic tumors (schwannoma, neurofibroma). GISTs were only recognized as a separate entity fairly recently. They now can be differentiated from leiomyomas and schwannomas by their immunohistochemical and genetic characteristics20,75,102,153,155–157 (Table 14.6). GISTs are now defined as mesenchymal spindle cell, epithelioid, or rarely pleomorphic tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, which—in contrast to myogenic or neurogenic tumors-are driven by oncogenic, mutational gain-of-function activation of KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-a (PDGFR-a). Most GISTs express KIT protein (stem cell factor receptor protein, CD117) (= 95%), the chloride channel protein DOG1 (>95%), and CD34 (70%)20,154,155,157,159–162 (Table 14.6). Histogenetically, these tumors probably originate from gastrointestinal pacemaker cells (interstitial cells of Cajal) or a pluripotent precursor cell. The relative risk of malignant behavior of a GIST primarily depends on the number of mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPF), on its size, on certain types of mutation, and on its location in the gastrointestinal tract. If their anatomic site is not taken into consideration, only GISTs smaller than 5 cm and with a low mitotic index (<5/50 HPFs) have a low risk of malignant behavior.20,153,163 Taking the anatomic location into account, clinically malignant behavior is less frequent in the case of gastral GISTs (20–25%) in comparison with GISTs located in the small intestine or rectum (40–50%)154,155,164–166 (Tables 14.7 and 14.8).

Myogenic tumors (leiomyoma, glomus tumor, leiomyosarcoma) |

Leiomyoma: 75% spindle cell pattern, 25% epithelioid pattern; always benign; in the esophagus in almost all cases arising from the muscularis propria, in the large intestine preferentially from the muscularis mucosae |

Immune phenotype: • Positive: smooth muscle actin (SMA) (100%), desmin (100%) • Negative: NSE, PGP9.5, S100, CD117, CD 34, DOG1, vimentin |

Leiomyosarcoma: very rare, arising always from the muscularis propria |

Immune phenotype: • Positive: SMA (100%), desmin (63%) • Occasionally positive: CD34 • Negative: CD117 |

Neurogenic tumors (peripheral nerve sheath tumors = schwannoma) |

Rare, usually located in the stomach, very rarely in the esophagus or intestine |

Nearly always benign |

Typically spindle cell pattern, rarely epithelioid or plexiform pattern |

Immune phenotype: • Positive: S100 (100%), glial fibrillary acidic protein (64–100%), collagen type IV • Occasionally positive: CD34 • Negative: SMA, desmin, CD117, DOG1 |

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) |

70–80% spindle cell type, 20–30% epithelioid type, 10% mixedtype |

c-kit mutations in 75–80%, PDGFRα mutations in 8% |

< 5% associated with tumorsyndromes (neurofibromatosis type I/von Recklinghausen disease, Carneytriad, familial GIST syndrome) |

Association with other malignancies (4.5–33%, mean 13%) |

Inherent potential for malignant behavior (stomach 20–25%; small intestine, rectum: 40–50%) |

Subgroup: gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumor (GANT) |

Occurrence: 60% stomach, 20–30% small intestine, 5% duodenum, 5% large intestine and rectum, <5% esophagus, 1% extra-intestinal |

Immune phenotype: • Positive: CD117 (>90%), DOG1 (>90%), CD34 (overall 60–70%; rectum and esophagus: 95–100%; stomach: 80–85%; small intestine: 50%), vimentin • Occasionally positive: SMA (20–40%) • Negative: glial fibrillary acidic protein, desmin (<2%), S100 (< 5%) |

CD34, transmembrane sialomucin glycoprotein of unknown function; CD117, transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor protein KIT; c-kit, c-kit proto-oncogene, coding for the transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor protein KIT; DOG1 (discovered on GIST-1), antibody against a chloride channel protein (protein kinase C theta) of unknown function; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; PDGFRa, platelet-derived growth factor receptor a; PGP9.5, protein gene product 9.5; SMA, smooth muscle actin; S100, dimeric acidic calcium-binding protein, regulating calcium flux of nerve cells.

Risk of malignant behaviora | Tumor size (cm) | Number of mitoses per HPFb |

Very low risk | <2 | <5/50 |

Low risk | 2–5 | <5/50 |

Intermediate risk | <5 | 6–10/50 |

5–10 | <5/50 | |

High risk | >5 | >5/50 |

>10 | Any mitotic rate | |

Any size | >10/50 |

a Defined as metastasis or tumor-related death.

b High-power field (HPF), defined as the area visible using 400x magnification level.

Older reports need to be viewed in the light of the recent change in the classification of mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. A recent pathological study that examined archived tissue of subepithelial mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, previously classified as smooth-muscle tumors (leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas), showed that with the exception of esophageal tumors, most of the lesions were actually GISTs.154,196

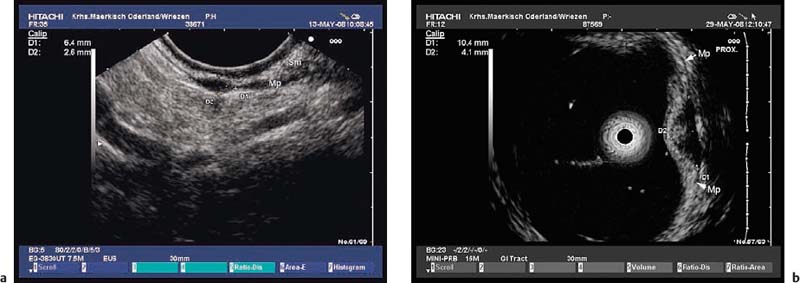

Epidemiological data on the frequency and the natural course of GIST are scarce. The incidence of clinically relevant GISTs is = 10–20 per 1 million people. Most of the tumors are detected in individuals in the fifth or sixth decades of life.16,155 A recent systematic review has shown that gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common presentation of GIST, with a pooled prevalence of 33%. Other common symptoms are abdominal pain (pooled prevalence 19%), iron-deficiency anemia (8.9%), palpable abdominal mass (6.9%), weight loss (4%), dysphagia (3%), and intestinal obstruction (3%).17 In large population-based studies, only 15–30% of GISTs were discovered incidentally. On the other hand, very small GISTs (minute GISTs, microscopic GISTs, seedling GISTs, GIST tumorlets: 0.2–12.0 mm) are a very common finding in postmortem examinations and surgical resections of the proximal stomach and esophagogastric junction (9–35%), but not in intestinal resection specimens (≤ 0.1%) (Fig. 14.30).7,158,167–170

The clinical presentation of GISTs varies widely and includes incidentally found small benign tumors, tumors of uncertain prognosis, and clinically overt malignant tumors with predominantly hepatic and peritoneal metastases. Conversely, lymph-node metastases are exceedingly rare and occur preferentially in patients under the age of 40.12,171

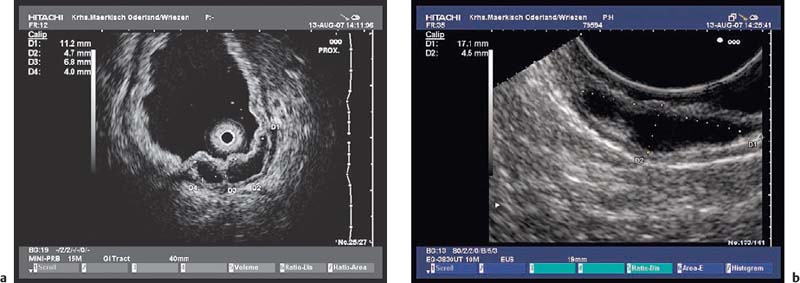

Fig. 14.30a, b “Seedling” mesenchymal subepithelial tumors of the stomach, < 10 mm in size. Mp, muscularis propria; Sm, submucosa.

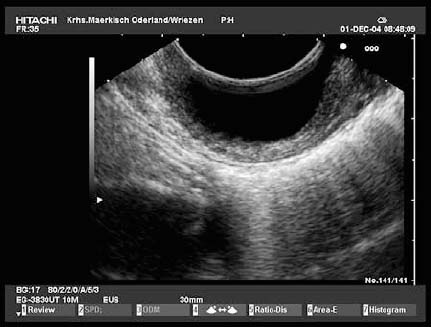

Leiomyomas (i.e., benign gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors with muscular differentiation) are most often found in the esophagus, sometimes also in the gastric cardia and colon, and in rare cases in the stomach, small intestine, and rectum. They are related to the second hypoechoic layer (lamina muscularis mucosae) as well as to the fourth hypoechoic layer (tunica muscularis propria). Endosonographically, they appear as homogeneously hypoechoic, sometimes almost anechoic tumors with smooth margins. Occasionally, leiomyomas may contain calcifications (Fig. 14.31).172,173,183–185,212,216,217

Leiomyosarcomas are very rare in the gastrointestinal tract and occur in the intestine with a frequency of 2–10% of that of GISTs.102,155,156,173,185,212,216,217

Schwannomas (peripheral nerve sheath tumors) are the most infrequent subepithelial mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Of 191 gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors evaluated by Kwon et al., only 12 (6.3%) were schwannomas.174 They originate from the tunica muscularis propria and usually occur in the stomach (60–70%) or colon (20–30%), or rarely in the small intestine, rectum, and esophagus. With regard to their gross morphology, these S100-positive spindle cell, rarely epithelioid and in some cases plexiform tumors resemble GISTs. A peripheral lymphoid cuff is observed in almost all cases; a fibrous capsule, on the other hand, is rare. Gastrointestinal schwannomas always behave in a benign fashion.156,174–177 Endosonography typically shows very hypoechoic, homogeneous, well-demarcated masses arising from the deep muscle layer with a marginal hypoechoic halo, corresponding to the lymphoid cuff.178–180

Depending on their size and age, leiomyomas, low-risk GISTs, and schwannomas may develop regressive changes that appear as anechoic or hyperechoic regions, and they may develop an irregular shape, which may make it difficult or impossible to differentiate them from malignant mesenchymal tumors.

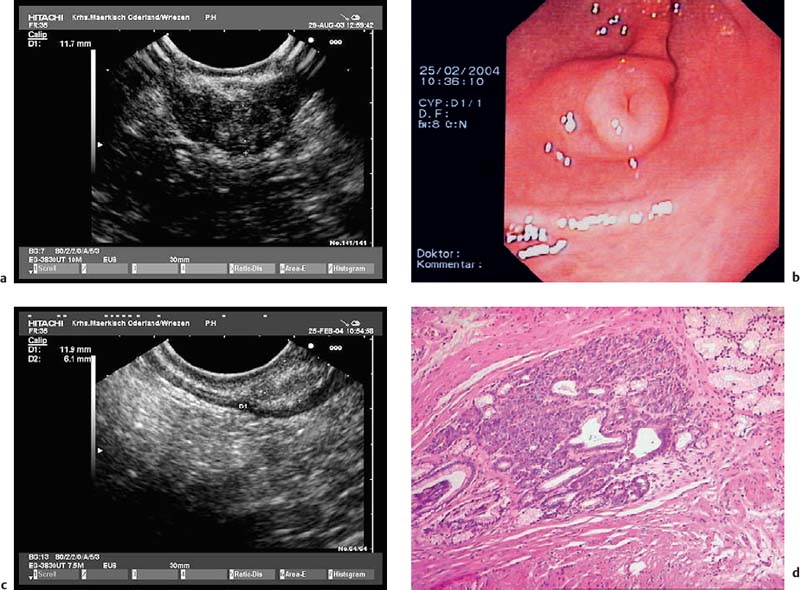

Fig. 14.31a—d Subepithelial leiomyomas in the esophagus and stomach.

a, b Hypoechoic, homogeneous tumors with smooth margins originating from the fourth echolayer in the esophagus. Mp, muscularis propria.

c A small subepithelial tumor in the gastric body, with extensive calcification and dorsal signal extinction, making it impossible to identify the layer of origin (15-MHz ultrasound miniprobe).

d A leiomyoma in the gastric cardia: very hypoechoic, middle-sized tumor, originating from the fourth sonographic layer. Mp, muscularis propria.

Endosonographic differentiation of subepithelial mesenchymal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract. It is mandatory to distinguish between GISTs and other mesenchymal subepithelial tumors, as leiomyomas and schwannomas are truly benign and their clinical management therefore differs considerably from that of GISTs. However, only two studies, including 77 gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors, have reported endosonographic differences between GISTs, myogenic, and neurogenic mesenchymal gastrointestinal tumors. A marginal halo is a common feature of both GISTs and schwannomas, but not of leiomyomas. GISTs are usually less hypoechoic than the normal tunica muscularis propria. By contrast, the echogenicity of leiomyomas and schwannomas is quite similar to that of the deep muscle layer. Inhomogeneity of the tumor, hyperechogenic spots and (only in one of the two studies) lobulation of the tumor surface were observed more frequently in GISTs than in leiomyomas.181,182 However, endosonographic criteria alone are not sufficient to distinguish reliably between GISTs and other mesenchymal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract.12,18,27,34,182 In various studies, 74–83% of mesenchymal tumors in the esophagus were small muscle tumors (leiomyoma and very infrequently leiomyosarcoma).75,157,173,185 Small mesenchymal tumors in the muscularis mucosae of the colon and rectum are always benign leimomyomas.183 Conversely, a hypoechoic tumor of the stomach has a 69–94% likelihood of being diagnosed as a GIST on histopathological examination.75,157,196 Similarly, subepithelial mesenchymal tumors in the duodenum (93%)157,212 and small intestine (83–100%)186 are most likely to be GISTs. The anatomic location is therefore a more important clue to the differential diagnosis of a hypoechoic tumor of the gastrointestinal tract than subtle differences in the endosonographic appearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree