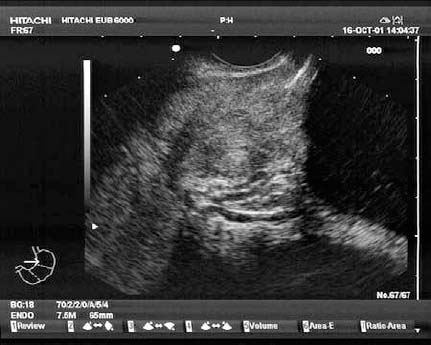

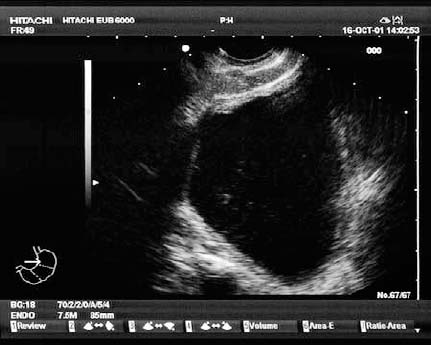

26 Endoscopic Ultrasound of the Colon Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) examination of the colon is possible, particularly using radial scanning techniques with an orthograde endoscopic view. Longitudinal probes in which the endoscopic view is not orthograde are more difficult to use, and this may complicate examinations in certain cases. Endosonography can be helpful in evaluating submucosal colonic tumors in which the benign or malignant status is unknown. In these cases, the ideal combination of diagnostic methods—such as colonoscopy for precise localization and visualization of the findings and subsequent endosonography (e.g., using instilled water for optimal imaging conditions)—remains a challenge. Miniprobe technology has proved to be superior to conventional endosonography in the colon (with the exception of the rectum), since tumors or polyps can be visualized, examined, and classified in the same way as in the approach used for esophageal, gastric, and duodenal wall endosonography. Although the place of miniprobe technology has not yet been sufficiently evaluated, it will probably offer a wide range of further indications. Fig. 26.1 The prostate, with the urethra. The relevance of flexible endosonography techniques in the lower intestinal tract is a matter of controversy.1–14 There are as yet no universally accepted indications for endosonography of the colon. In contrast, rectal endosonography using rigid probes is widely used and, in the hands of an experienced examiner, can play an important role in the diagnosis of complicated fistulas and in the staging of rectal carcinomas. In some cases, endosonography may also be helpful for EUS-guided puncture. With further technical improvements and more widespread use of high-frequency miniprobe technology, an extended range of indications for endosonography in the lower gastrointestinal tract can be expected, particularly since lesions can be visualized endoscopically and their intramural and transmural extension can be assessed during the same examination. The cecal pole and ileocecal valve can be reached with guidance from landmark structures and surrounding organs such as the prostate, seminal vesicle, urinary bladder, psoas muscle, left kidney with hilum, spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, liver, right kidney, and head of the pancreas (Figs. 26.1, 26.2, 26.3, 26.4, 26.5, 26.6, 26.7, 26.8, 26.9, 26.10, 26.11, 26.12, 26.13, 26.14, and 26.15). Fistulas, abscesses, and other pathological transmural findings can be visualized with a high level of sensitivity (Figs. 26.16 and 26.17). Fig. 26.2 The urinary bladder, with sporadic echoes caused by sediment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree