Fig. 20.1

Lateral View: A 16 g Coude needle enters the caudal canal

4.

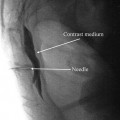

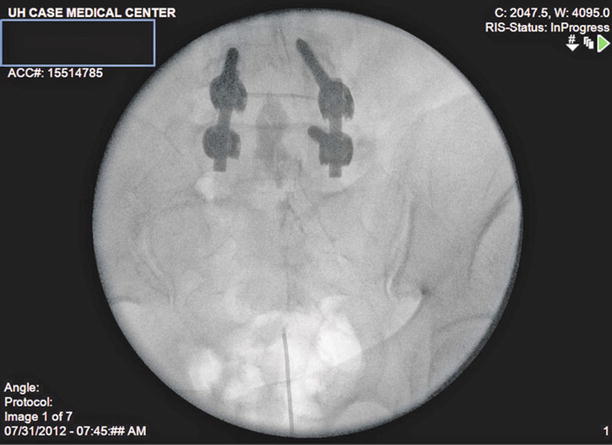

After negative aspiration for cerebrospinal fluid and blood, 5–10 ml of nonionic water soluble contrast (either Omnipaque 240 or Isovue 300) is injected smoothly under live fluoroscopy. An unremarkable epidurogram may have a “Christmas tree” pattern, the central canal making up the “trunk” of the tree and the nerve roots the “branches.” An abnormal epidurogram will reveal filling deficits in areas of the presumed fibrosis (Fig. 20.2). This filling deficit should clinically correlate with the patient’s symptoms before proceeding with the next step. There are some clinicians that perform the epidurogram after the catheter is in place by the suspected site of fibrosis (Fig. 20.3).

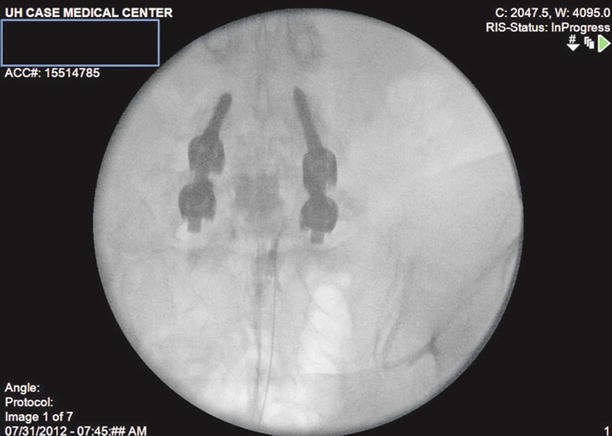

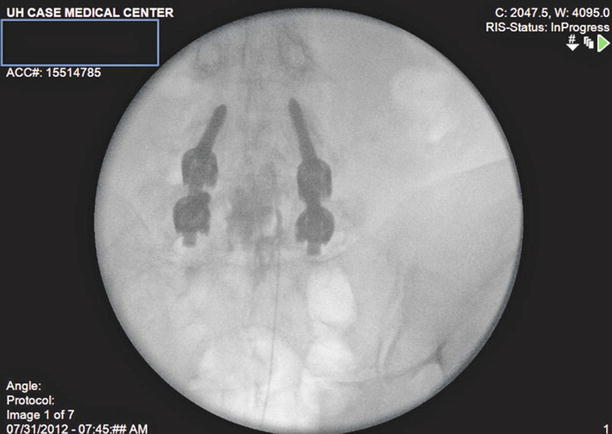

Fig. 20.2

Epidurogram: Injection of 2 ml of iohexol 240 with spread of contrast to L4/L5 junction with filling defect along right L5 nerve root

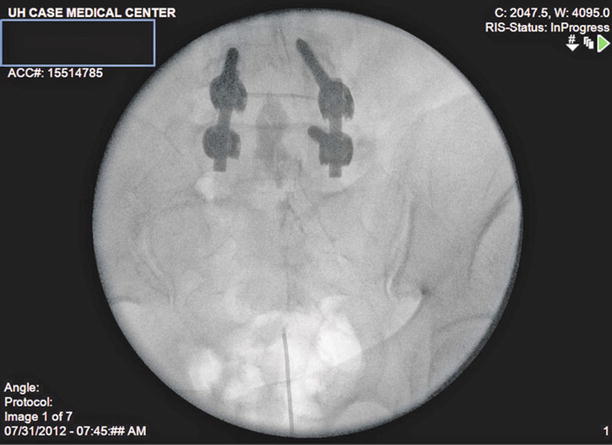

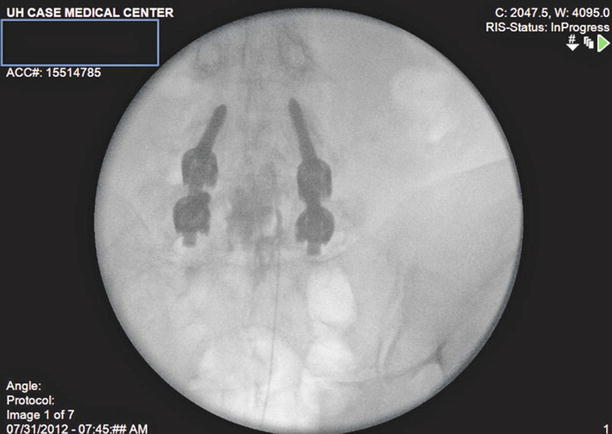

Fig. 20.3

Lateral View: The Racz catheter is advanced into the anterior epidural space until resistance is met

5.

If the filling deficit correlates with symptoms, then a Racz Tun-L-Kath® or similar flexible catheter should be directed toward the area of filling deficits (Fig. 20.4). Placing a small bend to the tip of the catheter may improve the ability to steer toward these areas of filling deficits. A 30° bend in the first 1–2 cm of the catheter should be sufficient. Ventral placement of the catheter should be confirmed under lateral fluoroscopy.

Fig. 20.4

AP View: The Racz catheter is seated more towards the filling defect on the right. The bevel is biased to the right side

6.

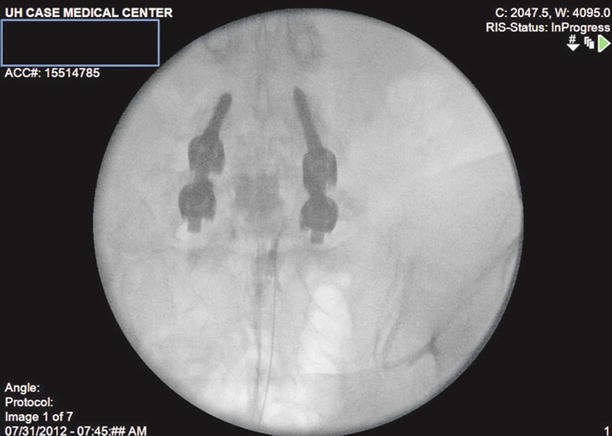

After correct placement, inject 10 ml of preservative-free normal saline with or without 1,500 units of hyaluronidase into the area surrounding the filling defect. Follow this with 2–3 ml more of contrast to visualize opening of the scarred area and spread of the injectate in the epidural space (Fig. 20.5).

Fig. 20.5

Repeat injection of local anesthetic with mechanical manipulation of catheter results in advancement of the catheter to top of L5 vertebral level

Fig. 20.6

Further catheter manipulation and contrast injection results in expansion of contrast spread to mid L4 vertebral level

Fig. 20.7

Final medication spread after depositing local anesthetic and steroids. Contrast has spread well into L4 and along the contour of the right L5 nerve root

7.

Prepare a 10-ml syringe of 9 ml of 0.5 % lidocaine and 40 mg/ml of triamcinolone diacetate. Other common corticosteroid preparations include 40–80 mg methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol®), 25–50 mg triamcinolone diacetate (Aristocort®), 40–80 mg triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog®), and 6–12 mg betamethasone (Celestone Soluspan®) [36]. Administer a 3-ml test dose and wait for several minutes to confirm no signs of intrathecal injection. Resume the smooth injection of the rest of the syringe if the test dose reveals no untoward signs.

8.

Remove the needle under live pulsed fluoroscopy and secure the catheter to the skin with tape. Place triple antibiotic ointment over the puncture site and place sterile dressings. Attach a bacteriostatic filter to the catheter.

In the postanesthesia care unit 20 min later:

1.

Infuse 10 ml of 10 % hypertonic saline over the course of 30 min. If the patient complains of pain, add several ml of 0.5 % lidocaine, wait for 5 min, and then resume.

2.

At the end of the infusion, flush the catheter with preservative-free normal saline.

On days 2 and 3:

1.

Inject 10 ml of 0.5 % lidocaine, wait for 25–30 min, and then infuse 10 ml of 10 % hypertonic saline over 30 min.

2.

Flush catheter with 2 ml of preservative-free NS.

3.

Repeat above on day 3, remove catheter, and place sterile dressings.

Modified Techniques [23] (Day 1)

The entrance into the caudal space is performed as described above. Adhesiolysis is carried out utilizing a Racz® catheter (EpiMed International, Inc.), with final positioning of the catheter on the side of the defect and the source of pain and an additional injection of contrast to identify successful adhesiolysis.

1.

Following the completion of the adhesiolysis and repositioning of the catheter, an injection of 5 ml of lidocaine 1 % preservative-free with 6 mg of betamethasone phosphate acetate mixture should be injected.

2.

After waiting 10–15 min, provided that there is no evidence of subarachnoid blockade, 6 ml 10 % sodium chloride solution in two divided doses of 3 ml over 10–15 min is administered. The catheter is then removed, and the patient may be discharged home when stable.

Endoscopic Lysis of Adhesions

The first in vivo exam of the spinal canal was performed by J. L. Pool in 1937 and was complicated by hemorrhage. Through persistence and refinement of his technique, he was able to document over 400 cases by 1942 with successful observation and identification of neuritis, herniated nucleus pulposus, hypertrophied ligamentum flavum, neoplasms, and arachnoid adhesions [37, 38].

Further improvements in endoscopy and fiber-optic light sources improved percutaneous placement. Ooi and Morisaki from Japan were credited for these advancements throughout the 1960s and 1970s [37]. Shimoji and associates were the first to report the concomitant use of fiber-optic light sources and flexible fiber-optic catheters instead of rigid metal endoscopes. Fluoroscopy was used in conjunction with their technique which aided in identifying the spinal level in view. Significant anatomical findings including aseptic adhesive arachnoiditis and clumped nerve roots were also visualized with the use of this new technology [39]. Epiduroscopy may be useful in confirming a physiological basis for radiculitis when other diagnostic studies such as MRI are negative [37]. Direct visualization can be used to confirm clinical observations that may not otherwise be discovered by traditional tests. This would be a strong indication to use this technique over a percutaneous route if the practitioner has had appropriate training and experience.

Endoscopic Technique

The patient is placed into a prone position. Standard American Society of Anesthesiology recommendations for moderate sedation should be used. Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered prior to the start of the procedure.

1.

After proper sterile preparation and draping, a skin wheal is raised over the sacral hiatus using 1–2 ml of 1 % lidocaine with a 25-gauge needle. A 16-gauge RK needle is then advanced into the hiatus under lateral and AP fluoroscopy.

2.

An epidurogram is then performed with the injection of 10 ml of nonionic contrast dye.

3.

A 0.9-mm guide wire is inserted through the needle, which is then advanced under fluoroscopic guidance to the level of suspected pathology and contrast filling defect. This is followed by a small incision with a #11 blade and advancement of a 9-French dilator with catheter (sheath) over the guide wire.

4.

Once the catheter is advanced to the tip of the guide wire, the wire is removed. Following this, a 0.8-mm fiber-optic spinal endoscopic video-guided system is introduced into the catheter through the valve and is advanced until the tip is positioned at the distal end of the catheter, as determined by video and fluoroscopic images. The endoscope should be placed ventrolaterally toward the suspected side of the lesion.

5.

In conjunction with gentle irrigation using normal saline, the catheter and fiber-optic endoscope are manipulated and rotated in multiple directions, with visualization of the nerve roots at various levels. Gentle irrigation is carried out by slow, controlled infusion. It is recommended that the infusion rate of saline irrigation should not exceed 30 ml/min and that the total infused volume should be less than 100 ml. (There will be retrograde flow that should not be counted toward the total volume) [37]. For prolonged cases with larger irrigation volumes, a continuous subarachnoid needle may be placed for continuous CSF pressure monitoring. Adhesiolysis and decompression are carried out by distension of the epidural space with normal saline and by mechanical means utilizing the fiber-optic endoscope. Visualization will be achieved only if the epidural space is kept distended by repeated injections of saline. Some structures that may be easily visualized include the dura mater.

6.

Confirmation is accomplished with the injection of nonionic contrast material, and an epidurogram is performed on at least two occasions. Following completion of the procedure, generally, lidocaine 1 %, preservative-free, mixed with 6–12 mg of betamethasone acetate or 40–80 mg of methylprednisolone is injected after assuring that there is no evidence of subarachnoid leakage of contrast.

7.

If pathology is determined to be at multiple levels, the procedure can be carried out at multiple levels, and the injectate should be injected in divided doses.

Complications

The usual risks of an invasive epidural procedure exist. The most commonly reported complications in percutaneous and endoscopic adhesiolysis include dural puncture, bleeding, infection, damage to blood vessels and nerves, unintentional dural puncture, inadvertent injection of medications, and catheter shearing [40].

Catheter shearing can occur as a result of frequent adjustment of the catheter against the needle. A Tuohy needle should not be used for this procedure as the back edge of the needle is a cutting surface and would shear the catheter [33]. Methods to minimize this include placement of the initial needle tip in the direction of the suspected lesion. This will minimize the amount of times the catheter will need to be adjusted and steered. Catheter shearing can present a problem of retained hardware. Removal of the catheter can require surgical intervention or the use of epidural endoscopy. Manchikanti described a case where this occurred, and the use of endoscopy alone was not sufficient, ultimately arthroscopy forceps where utilized to remove the catheter [41].

Other cases have been reported where fragments of the Racz catheter were sheared off and trapped in an L5-S1 foramen. Karaman and colleagues report on an incident where the catheter fragment was left in position in the epidural space. Careful monthly follow-up for a year revealed the patient to respond well to the neurolysis, and a decision was made to forgo an aggressive surgical resection to recover the very small fragment [42].

Until recently, there had been no published reports of serious side effects like arachnoiditis, paralysis, or bowel or bladder dysfunction. Justiz and colleagues describe the case of a 73-year-old woman who opted for endoscopic lysis of adhesions for severe scarring of the epidural space. Subsequently, the patient developed a neurogenic bladder with urinary retention. Three years later, she experienced resolution of the neurogenic bladder symptoms that coincided with the use of the antibiotic nitrofurantoin. Upon discontinuation of the antibiotic, the patient noted that she was unable to void spontaneously. With reinstitution of nitrofurantoin, the patient was once again able to void effectively and has been maintained on nitrofurantoin for >3 years [2].

Infection is a frequent concern when performing any neuraxial technique. Strict aseptic technique should be standard practice; however, infections still occur. Meningitis is a rare but reported complication of this particular procedure as well. Wagner and colleagues reported an incidence of severe meningitis with significant neurological sequelae after an epidural lysis of adhesions for unspecific low back pain. They cautioned that this procedure should be done under strict aseptic technique [43]. It is recommended to proceed with careful patient selection before embarking on this intervention to reduce overall complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree