Epidural steroid injections have been used for decades as part of a rehabilitation program to relieve back or neck pain and the associated radicular nerve component that often accompanies these problems. These injections are minimally invasive and offer many patients substantial relief without the need for more invasive procedures. Although effective and generally simple, they must be performed accurately and properly for maximum benefit and complication avoidance. This article discusses the various technical aspects of the procedure that must be observed by the operator to accomplish these ends.

Low-back and neck pain are frequent complaints among patients, as well as a leading cause of doctor visits and loss of work in the United States each year. It is estimated that up to 5% of adults seek medical attention for back pain annually. The cost of back pain exceeds 100 billion dollars in the United States alone. Many of these patients may proceed to surgery in an attempt to eliminate pain and recover functionality, which adds additional cost and complexity to the treatment paradigm and is now believed to offer no long-term advantage compared with more conservative treatment modalities for the vast majority of patients experiencing pain without motor symptoms. In the prospective Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), surgery was found effective for rapid pain relief but both groups (surgical and conservative management) faired similarly in matched-control comparisons at 2-year follow-up. There was no demonstrated risk in undergoing conservative management compared with early surgical intervention (a long-term warning that has been heard from surgeons lobbying against conservative treatment and for early surgery).

Because many patients will recover from back pain without surgery, it seems reasonable, as well as cost effective, to try conservative therapy in the vast majority of patients before progressing to surgery. Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) serve as a part of a conservative, therapeutic approach to pain management in these individuals.

History

Epidural injections of anesthetics were reported over a century ago in Europe. Steroid injections into the epidural space began in the 1950s. Since then, there have been numerous publications attempting to analyze the results of these injection procedures for control of back and radicular pain. The results are mixed, and most opinions can be supported by selected data. Therefore, trying to prove utility, or not, is difficult on the basis of available data (much of which was anecdotal and without control). There is definitely a body of information that indicates improved outcome (reduced pain and quicker return to work) with epidural steroids. Those who administer ESIs daily in pain practices see a substantial percentage of patients who get welcome benefit from these simple procedures. They have become a common component in the process of providing pain relief and increased mobility while patients undergo other rehabilitation procedures and recovery.

Historically, referrals for ESIs came from surgeons. Patients were sent to them by primary care providers for surgical evaluation. Many patients had been treated with pain medicines and had been waiting for the magic referral only to find out that now they would need to have imaging, rehabilitation, or ESI. It is likely that the process had already been weeks long. Today, ESI referrals are more often directly from the primary care physician. The process of ESI can be started early while the patient is waiting to see the surgeon. This allows early intervention of pain and better participation in the rehabilitation procedures while awaiting the surgical consult (which could be canceled as pain improves with conservative treatment and time).

Patient selection

The patient considered for an ESI experiences pain that originates from the area to be treated. Patients with a short history of pain seem to do better than those with chronic pain (for longer than 6 months). Patients with pain resulting from disc herniation respond better to ESI than do patients with pain resulting from spinal stenosis. Patients who have not been operated on get better relief than those previously operated on and with epidural scar. Prior operation, chronic pain, or pain resulting from spinal stenosis is not a contraindication but does suggest that there will likely be a poorer outcome than for other groups.

Imaging is always helpful to correlate anatomic defects or abnormalities with the clinical presentation. However, imaging does not visualize pain, and, therefore, the clinical examination is of primary importance in determining where treatment should be applied. If there are no specific contraindications to ESI, the ESI can be initiated on the basis of clinical findings before imaging or while waiting for imaging to be obtained.

Patient selection

The patient considered for an ESI experiences pain that originates from the area to be treated. Patients with a short history of pain seem to do better than those with chronic pain (for longer than 6 months). Patients with pain resulting from disc herniation respond better to ESI than do patients with pain resulting from spinal stenosis. Patients who have not been operated on get better relief than those previously operated on and with epidural scar. Prior operation, chronic pain, or pain resulting from spinal stenosis is not a contraindication but does suggest that there will likely be a poorer outcome than for other groups.

Imaging is always helpful to correlate anatomic defects or abnormalities with the clinical presentation. However, imaging does not visualize pain, and, therefore, the clinical examination is of primary importance in determining where treatment should be applied. If there are no specific contraindications to ESI, the ESI can be initiated on the basis of clinical findings before imaging or while waiting for imaging to be obtained.

Contraindications

Because ESI is an injection into a space that contains vascular elements and that is out of reach to direct pressure, it cannot be used in patients who are on anticoagulants or who have coagulation defects. Coumadin and heparin obviously are contraindications to ESI because of the risk of epidural hematoma. Even with the use of 25- or 27-gauge needles, the risk is not completely eliminated. Less clear is the risk for patients taking platelet inhibitors such as aspirin or ticlopidine. Guidelines for cessation of antiplatelet drugs before epidural injections vary; so each individual society should be checked for their most recent recommendations. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia recommends being off ticlopidine for 14 days and off clopidogrel for 7 days. Recommendations are less specific for aspirin but seem to vary between 5 to 7 days.

Diabetes is not a contraindication, but steroid injections raise glucose levels and make their control more erratic for several days. Patients with brittle diabetes or those with poor control may need medication changes or closer monitoring after ESI.

ESI for patients with active infection (during antibiotic therapy) should usually be postponed until therapy is completed and signs of infection have cleared.

Image guidance

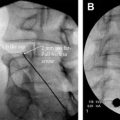

ESI without image guidance should be avoided. Evaluations have shown a 25% to 40% miss rate when these injections are performed without guidance. Misplaced injections result in lesser pain relief and raise the risk of secondary complications from steroid placed in unwanted locations such as the intrathecal space. Intrathecal steroid injections are associated with arachnoiditis.

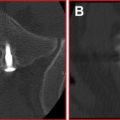

Generally, fluoroscopy is the method of choice for ESI. It offers quick, accurate, and cost-effective image guidance. Johnson and colleagues used fluoroscopy-guided ESIs in a large cohort of more than 5000 patients, with a complication rate of 0.07%. Several reports have described computed tomography (CT) for guidance, but all have comprised small numbers of patients and were anecdotal in quality. There is no proof that CT offers any advantage over fluoroscopy for safety and is definitely negative for time efficiency and cost.

Technical considerations

Local anesthesia is used before the introduction of the epidural needle. One percent lidocaine with bicarbonate is a commonly used local anesthetic. This material still has considerable sting and discomfort. For this reason, the author prefers a “no sting” mix that includes lidocaine, bicarbonate, and Ringer lactate ( Table 1 ). This mixture eliminates essentially all the discomfort to the anesthetic. It contains no preservative, and any excess must be discarded at the end of each day.

| Solution | Lidocaine (4%) (mL) | Lactated Ringer (mL) | Bicarbonate (mL) | Epinephrine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 24 | 2 | 0 mL |

| 2 | 4 | 24 | 2 | 0.15 mL |

| (1:1000) | ||||

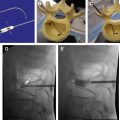

The needles used for ESI by the anesthesiologist were traditionally of the Tuohy type. This needle was rather blunt (to protect from easy puncture of the dura) and large (14 to 18 gauge). With image guidance there is no need for needles of this size or type. Routine use of a 25- or 27-gauge spinal (Quinke) needle allows easy epidural access with minimal trauma and discomfort.

Epidural injection of radiographic contrast is commonly done with image guidance to confirm appropriate epidural positioning before steroid injection. Nonionic contrast approved for intrathecal use is recommended, which prevents complications with inadvertent intradural injections. In patients with contrast allergy, loss of resistance technique can be used with only minimal loss of accuracy, as image guidance is still used for regional needle localization. This technique does eliminate the opportunity to prevent intravascular needle placement (and negative aspiration for blood does not exclude the possibility of intravascular positioning).

Some operators perform a full epidurogram before injecting steroids, although not necessary in the routine procedure. The epidurogram adds volume to the procedure (which can be problematic as some patients experience local pain during injection), and the information gained is rarely used to change the procedure in any meaningful way. Only a small volume of contrast, usually no more than 1 to 2 mL, is needed to confirm appropriate epidural location before injecting steroid. A small volume is all that is needed to insure that an intravascular position has been avoided as well. The site of the injection should be the expected site of abnormality based on clinical presentation. In some patients with spinal stenosis, injection of the level above is necessary to prevent barotrauma that can be produced by adding fluid volume to an already tight space. By injecting above the level, gravity helps move the steroid solution into the adjacent level while avoiding the barotrauma. Transforaminal injection in this situation is also a consideration.

ESI is usually a minimally painful procedure. Patients often experience a feeling of pressure but actual pain is uncommon. Pain may result from injecting too rapidly and discomfort can be volume related. When there is pain or discomfort, simply stopping or slowing the injection often results in quick subsidence or reduction of the discomfort. The injection can be completed with a slower infusion rate. Pain that is persistent or not responsive to stopping the injection should be a sign to move the injection to an adjacent level or to use another administration route. Paresthesia or pain can be a sign of an intraneural injection.

Transforaminal injections are an alternative to the traditional interlaminar route. Although low in risk (in the hands of an experienced operator), this route should be used for specific indications and not as the initial or routine method. There is more pain and discomfort associated with the transforaminal route and also more chance of complication. Complications with this method are rare in the lumbar area but frequent enough in the cervical region that some pain practices have abandoned this method entirely. The use of CT, nonparticulate steroid (dexamethasone), or needle placement within a specific location within the foramina does not eliminate this risk. The operator is faced with a potentially devastating complication (cervical cord or brainstem stroke) while trying to treat a benign disease with a temporary therapy. This is a sure prescription for a lost malpractice case. (The author stopped doing cervical transforaminal injections in 2005 because of the awareness of multiple such malpractice cases and has seen no significant loss of effectiveness with standard cervical ESI alone.)

After a successful injection, the patient is returned to the observation area or waiting room and released after a 30-minute interval of uneventful recovery.

There is a long history of use associated with ESI treatments that have contributed to an entrenched dogma concerning the number of injections per year and interval between injections. None of these beliefs are based on scientific data or significant trial outcomes and therefore should be flexible. Treatment should be individualized to the patient’s presentation, needs, and response to therapy. The author routinely sees ESI patients for a reevaluation in 7 to 14 days after the prior treatment. Based on response to therapy, a repeat ESI is performed as needed at that time. Only 3 ESIs in a 6-month period, fewer if possible, are recommended to limit steroid exposure. The usual limit of 3 injections is more a historical one than a hard limit and can be adjusted as needed for some individuals. (However, if 3 or 4 injections do not fix the problem, then neither will 30.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree