Pain that develops in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spine is typically initiated from a clinical condition called spondylosis. Radiofrequency ablation is a key element in the treatment protocol of patients with spondylosis of the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacroiliac joint pain. A diagnosis can be made by blocking the median branch nerve that innervates each joint. Once this has been confirmed, an ablation procedure can be performed to increase the duration of pain relief desired by the patient with chronic pain originating from spondylosis. Radiofrequency neurolysis is a common technique used in the treatment of chronic pain, particularly facet (zygapophyseal joint) arthralgia. The technique involves an insulated needlelike cannula; x-rays passing through the patient show the projected relative radioopaque bony landmarks and the metallic cannula.

Lumbar facet joints were recognized as potential sources of back pain by Goldthwait as early as 1911. The term facet syndrome, defining lumbosacral pain with or without sciatic pain, was coined by Ghormley in 1933. Badgley in 1941 suggested that facet joints themselves could be a primary source of pain separate from spinal nerve compression pain; he attempted to explain the role of facet joint pain in large numbers of patients with low back pain whose symptoms were not caused by a ruptured disc. Multiple investigators described the pattern of pain caused by facet joint stimulation. Bogduk and colleagues showed that facet joint pain can be relieved by anesthetizing the facet joints responsible for low back pain, mainly by anesthetizing the median branch nerve that innervates the actual joint.

The prevalence of persistent low back pain secondary to the involvement of lumbosacral facet joints has been described in controlled studies as varying from 15% to 45% based on types of population and settings studied. Lumbar facet joint interventions are useful in the diagnosis and the therapeutic management of chronic low back pain. Common indications for lumbar diagnostic facet joint interventions are:

- ■

Somatic or nonradicular low back and/or lower extremity pain . Duration of pain of at least 3 months with an average pain level of greater than 5 on a scale of 0 to 10. Intermittent or continuous pain causing functional disability, failure to respond to more conservative management, including physical therapy modalities with exercises, chiropractic management, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, aqua therapy, and medical management.

- ■

Lack of disc herniation or evidence of radiculitis with no contraindications with understanding of consent, nature of the procedure, needle placement, and sedation . No history of allergy to contrast administration used, no contraindications or inability to undergo physical therapy, chiropractic management, or inability to tolerate nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications. Positive response to controlled comparative local anesthetic blocks for therapeutic interventions.

Common contraindications for lumbosacral facet joint interventions are:

- ■

Suspected or proven discogenic, sacroiliac joint, or myofascial pain infection

- ■

Anticoagulant therapy

- ■

Nonaspirin combination antiplatelet therapy

- ■

Pregnancy

- ■

Bleeding diathesis.

Pathophysiology

Lumbar facet joints have been shown to produce low back and referred lower extremity pain in normal volunteers. Stimulation of lumbar facet joints with injections of hypertonic saline or contrast medium produces back pain and somatic referred pain identical to that commonly seen in patients.

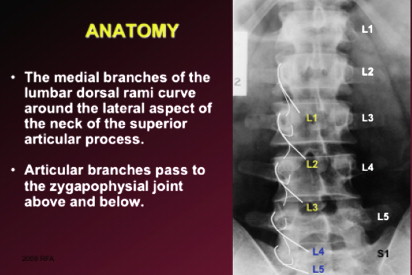

This pain also can be relieved by anesthetizing the lumbar facet joints deemed to be responsible for low back pain or the median branch nerve that innervates the joint itself. Pain originating from lumbar facet joints is predominantly present in the low back, buttocks, and thighs; however, it does not follow a reliable segmental pattern. The radiation of referred pain below the knee as far as the foot has been described, but typically pain predominantly involves the proximal parts of the lower extremity.

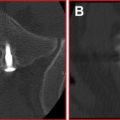

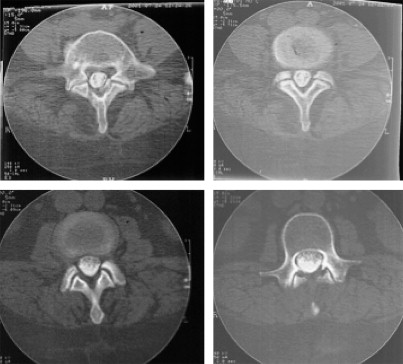

The prevalence of facet joint pain as a cause of low back pain has been studied extensively but its pathophysiology and diagnosis remains elusive. Lumbar facet joints can be affected by rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or ununited epiphyses of the inferior articular processes. The intraoperative reports excising the facet joints have demonstrated changes similar to those of chondromalacia of the patella. Evidence from controlled studies has been unable to establish that facet joint pain is caused by osteoarthritis of facet joints. On plain radiographs, facet joint arthritis appears as commonly in asymptomatic individuals as in patients with back pain. The data from radiological evaluation preclude making the diagnosis of pain of facet joint origin from either plain radiography or computerized tomography (CT) scanning ( Figs. 1 and 2 ).

The data also indicate either that osteoarthritis is not a cause of facet joint pain or, when it is, that the pain is caused by some factor other than the simple radiological presence of this condition.

Assertions that facet joint arthritis is usually secondary to disc degeneration or spondylosis may not be true, because in approximately 20% of cases facet joint arthritis can be a totally independent disease; and correlation between discogenic pain and facet joint pain or a combination of discogenic and facet joint pain has not been established thus far.

Diagnostic facet joint blocks

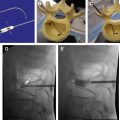

Lumbosacral facet joints can be anesthetized either with intraarticular injection of local anesthetic or by anesthetizing the medial branches of the dorsal rami that innervate the target joint ( Fig. 3 ).

The joint may be considered to be the source of pain if the pain is relieved by joint blockade. It is crucial to follow the required steps to eliminate false-positive responses. True-positive responses may be obtained only by performing controlled blocks. The controlled diagnostic blocks are performed either by placebo injections or by comparative local anesthetic blocks.

Neurophysiologic studies have shown that facet joint capsules contain low-threshold mechanoreceptors, mechanically sensitive nociceptors, and silent nociceptors. The lumbar facet joints have been shown to be capable of being a source of low back pain and referred pain in the lower limbs of normal volunteers ( Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Imaging technologies have not provided valid or reliable means of identifying symptomatic joints. The use of controlled local anesthetic facet joint blocks for the diagnosis of chronic low back pain has been reviewed and validated. Thus, placebo-controlled blocks or comparative local anesthetic blocks using 2 different local anesthetics of differing duration of action on 2 separate occasions, are the only means of confirming the diagnosis of facet joint pain.

Reliability

The face validity of intraarticular facet injections and medial branch blocks has been established by injecting small volumes of local anesthetic into the joint or onto the sensory nerves of the joint. The construct validity of facet joint blocks has been established.

The placebo effect of facet joint injections may be controlled by using strict criteria for determining positive response to controlled anesthetic blocks.

The theory that testing a patient first with lidocaine and subsequently with bupivacaine to identify placebo responders has been tested and proved.

Pain provocation response of facet joint injections has been shown to be unreliable. False-positive rates for lumbar facet joint blockade have been reported to be 17% to 49%. The false-negative rate for diagnostic facet joint blocks has been shown to be approximately 8% because of unrecognized intravascular injection of local anesthetic. There is a paucity of literature on the role of therapeutic facet joint blocks. However, facet joint pain may be managed by intraarticular injections, medial branch blocks, or neurolysis of medial branches.

Anatomy

The lumbar facet joints are formed by the articulation of the inferior articular process of 1 lumbar vertebra with the superior articular process of the next vertebra. The lumbar joints exhibit the features typical of synovial joints. The articular facets are covered by articular cartilage and a synovial membrane bridges the margins of the articular cartilages of the 2 facets in each joint. Surrounding the synovial membrane is a joint capsule that attaches to the articular processes a short distance beyond the margin of the articular cartilage. Ligaments connect the spinous process, laminae, and bodies of adjacent vertebrae. Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments help to stabilize these joints. The articular capsule surrounds facets and allows gliding motion. In the lumbar spine L4/L5 permits most flexion. The anterior longitudinal ligament attaches to anterior bodies and intervertebral discs. It is strong and prevents hyperextension. The posterior longitudinal ligament attaches to posterior bodies and intervertebral discs. It is weaker than the anterior longitudinal ligament and permits hyperflexion.

The ligamentum flava connects adjacent laminae of vertebrae and limits flexion. Intraspinal ligaments connect the spine; these are weak ligaments. Intraspinous ligaments and supraspinous ligaments connect spinous tips. Supraspinous ligaments are stronger than the intraspinous ligament and limit flexion. Intertransverse ligaments connect transverse processes and are weak ligaments.

Innervation

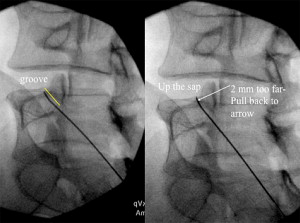

Each lumbar facet joint has dual innervation, being supplied by 2 medial branch nerves. The medial branches are of paramount clinical importance and relevance because they provide sensory innervation to the facet joints. The medial branches of the L1/L4 dorsal rami assume a constant and similar course. Each nerve emerges from its intervertebral foramen and enters the posterior compartment of the back by coursing around the neck of the superior articular process ( Fig. 6 ).

Hugging the neck of the superior articular process, the medial branch passes caudally and slightly dorsally, covered by the mamillo-accessory ligament, hooking medially around the caudal aspect of the root of the superior articular process to enter the multifidus muscle. Intermediate and lateral branches arise from the dorsal ramus at the same point as the medial branch. The medial branch crosses the vertebral lamina where it divides into multiple branches that supply the multifidus muscle, the interspinous muscle and ligament, and 2 facet joints.

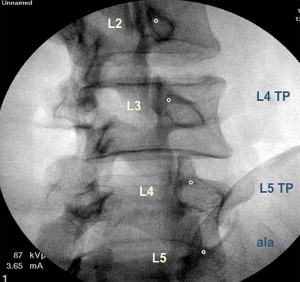

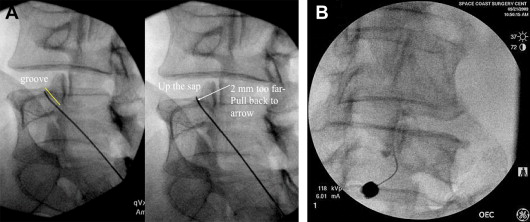

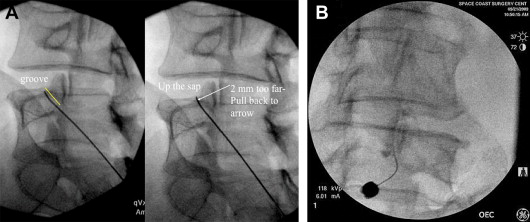

The medial branch of the L5 dorsal ramus has a different course and distribution than those of the L1/L4 dorsal rami. Instead of crossing a transverse process, the L5 dorsal ramus crosses the ala of the sacrum. The L5 dorsal ramus is much longer than typical lumbar levels. From the L5/S1 intervertebral foramen, the medial branch of the L5 dorsal ramus runs along the groove formed by the junction of the ala and the root of the superior articular process of the sacrum before hooking medially around the base of the lumbosacral facet joint ( Fig. 7 ).

Diagnostic facet joint blocks

Lumbosacral facet joints can be anesthetized either with intraarticular injection of local anesthetic or by anesthetizing the medial branches of the dorsal rami that innervate the target joint ( Fig. 3 ).

The joint may be considered to be the source of pain if the pain is relieved by joint blockade. It is crucial to follow the required steps to eliminate false-positive responses. True-positive responses may be obtained only by performing controlled blocks. The controlled diagnostic blocks are performed either by placebo injections or by comparative local anesthetic blocks.

Neurophysiologic studies have shown that facet joint capsules contain low-threshold mechanoreceptors, mechanically sensitive nociceptors, and silent nociceptors. The lumbar facet joints have been shown to be capable of being a source of low back pain and referred pain in the lower limbs of normal volunteers ( Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Imaging technologies have not provided valid or reliable means of identifying symptomatic joints. The use of controlled local anesthetic facet joint blocks for the diagnosis of chronic low back pain has been reviewed and validated. Thus, placebo-controlled blocks or comparative local anesthetic blocks using 2 different local anesthetics of differing duration of action on 2 separate occasions, are the only means of confirming the diagnosis of facet joint pain.

Reliability

The face validity of intraarticular facet injections and medial branch blocks has been established by injecting small volumes of local anesthetic into the joint or onto the sensory nerves of the joint. The construct validity of facet joint blocks has been established.

The placebo effect of facet joint injections may be controlled by using strict criteria for determining positive response to controlled anesthetic blocks.

The theory that testing a patient first with lidocaine and subsequently with bupivacaine to identify placebo responders has been tested and proved.

Pain provocation response of facet joint injections has been shown to be unreliable. False-positive rates for lumbar facet joint blockade have been reported to be 17% to 49%. The false-negative rate for diagnostic facet joint blocks has been shown to be approximately 8% because of unrecognized intravascular injection of local anesthetic. There is a paucity of literature on the role of therapeutic facet joint blocks. However, facet joint pain may be managed by intraarticular injections, medial branch blocks, or neurolysis of medial branches.

Anatomy

The lumbar facet joints are formed by the articulation of the inferior articular process of 1 lumbar vertebra with the superior articular process of the next vertebra. The lumbar joints exhibit the features typical of synovial joints. The articular facets are covered by articular cartilage and a synovial membrane bridges the margins of the articular cartilages of the 2 facets in each joint. Surrounding the synovial membrane is a joint capsule that attaches to the articular processes a short distance beyond the margin of the articular cartilage. Ligaments connect the spinous process, laminae, and bodies of adjacent vertebrae. Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments help to stabilize these joints. The articular capsule surrounds facets and allows gliding motion. In the lumbar spine L4/L5 permits most flexion. The anterior longitudinal ligament attaches to anterior bodies and intervertebral discs. It is strong and prevents hyperextension. The posterior longitudinal ligament attaches to posterior bodies and intervertebral discs. It is weaker than the anterior longitudinal ligament and permits hyperflexion.

The ligamentum flava connects adjacent laminae of vertebrae and limits flexion. Intraspinal ligaments connect the spine; these are weak ligaments. Intraspinous ligaments and supraspinous ligaments connect spinous tips. Supraspinous ligaments are stronger than the intraspinous ligament and limit flexion. Intertransverse ligaments connect transverse processes and are weak ligaments.

Innervation

Each lumbar facet joint has dual innervation, being supplied by 2 medial branch nerves. The medial branches are of paramount clinical importance and relevance because they provide sensory innervation to the facet joints. The medial branches of the L1/L4 dorsal rami assume a constant and similar course. Each nerve emerges from its intervertebral foramen and enters the posterior compartment of the back by coursing around the neck of the superior articular process ( Fig. 6 ).