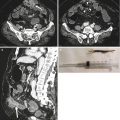

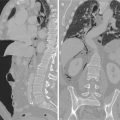

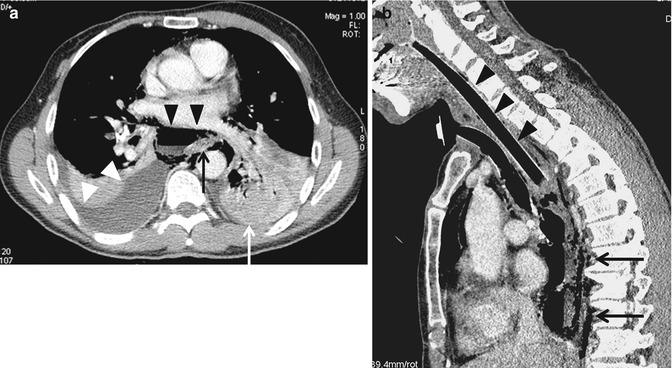

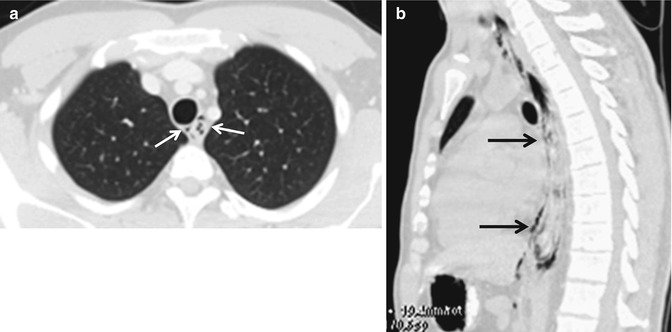

Fig. 4.1

Esophageal-pleural fistula after caustic ingestion: thickened esophageal (white arrow) and gastric (white arrowheads) walls; left pleural effusion (black arrows)

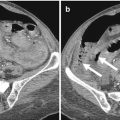

4.2 Iatrogenic Injuries

Iatrogenic injuries are the most common causes of EP. Many endoscopic procedures such as EGS, TEE, and EUS can result in an abnormal wall tension from instrumentation and subsequent transmural perforation (Fig. 4.2a, b). CT appearances of iatrogenic EP are variable depending on the site and size of perforation and the time elapsed since the onset of symptoms [7]. Beyond these frequent causes, we must remember palliative treatment of esophageal stenosis using laser therapy, electrothermal therapy, and stent placement (Fig. 4.3a, b). EP can also be a complication of sclerotherapy of esophageal varices and surgery of hiatal hernias and rarely occur during placement of Sengstaken-Blakemore tube or insertion of nasogastric tube [8]. A large number of most patients present the classic Mackler’s triad but someone have atypical symptoms and the diagnosis of EP is not initially suspected. Other patients have only one or two of the Mackler’s triad symptoms. In these cases, a history of a recent endoscopic procedure should recommend the execution of a CT scan because an early diagnosis improves the prognosis of these patients [2, 9].

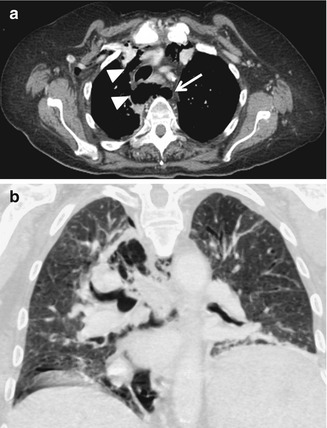

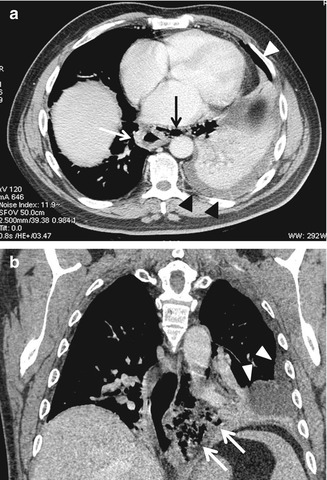

Fig. 4.2

(a, b) Iatrogenic perforations during endoscopy: esophagus (arrow) and extensive pneumomediastinum (arrowheads) with early subcutaneous emphysema on the right axilla

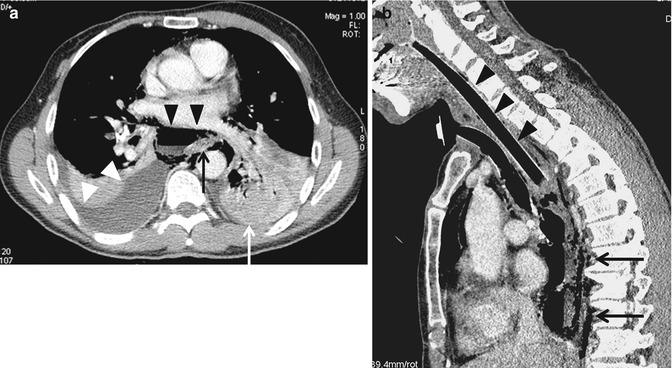

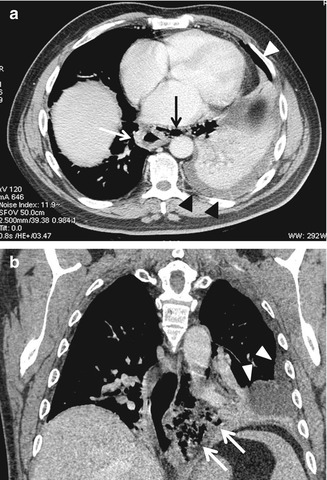

Fig. 4.3

(a, b) Esophageal perforation after stent placement: (a) pneumomediastinum (black arrowheads); Rigth pleural effusion (white arrowheads) left pleural effusion (white arrow); thickened esophageal wall (black arrow); (b) intraluminal esophageal stent (black arrowheads); pneumomediastinum (black arrows)

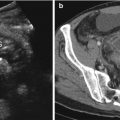

4.3 Intraluminal Pressure Increase

Intraluminal pressure increase is a frequent cause of EP. This increase may occur for iatrogenic causes, such as during stricture dilation as in achalasia (Fig. 4.4a, b) or, spontaneously, as in Boerhaave’s syndrome, in which an incomplete cricopharyngeal relaxation during vomiting results in abruptly intraluminal pressure increase, sufficient to breach esophageal wall [10]. In these cases the distal left posterior wall is the most common site of rupture, which results in a pneumomediastinum and left pleural effusion.

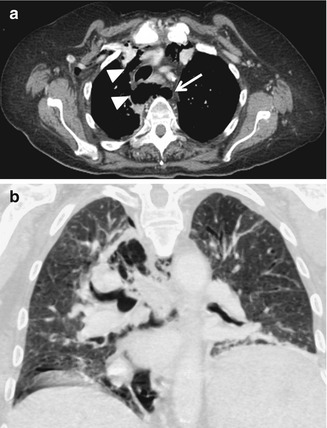

Fig. 4.4

(a, b) Esophageal perforation after stricture dilatation in achalasia: (a) thickened esophageal wall (white arrow); pneumomediastinum (black arrow); left pleural effusion (black arrowheads); pneumothorax (white arrowhead); (b) pneumomediastinum (white arrows); pleural effusion (white arrowheads)

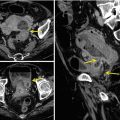

4.4 Foreign Bodies and Other Causes

The esophagus is a common site of impaction of swallowed foreign bodies. EP can occur directly, by full-thickness wall lesion, or indirectly by snap intraluminal pressure increase due to vomiting with an esophageal obstruction [11]. Direct wall perforation may be caused by sharp objects such as bones, dental work with hooks, pins and screws, or nails. In these cases, it can realize a periesophageal abscess formation [11, 12]. Improper foreign body removal by endoscopy can also cause determinate EP. In more difficult cases with a transfixed foreign body, you would prefer to shatter and then pull it out. Sometimes foreign bodies can cause only a mucosal lesion which can cause parietal pneumatosis (Fig. 4.5a, b). Neoplasm can also cause determinate EP. This happens in advanced lesions that cause a progressive wall erosion. Such events are often associated with bleeding [3]. EP due to gunshot or penetrating chest trauma are extremely rare. In most cases it comes to autopsy. However, in patients who have a thoracic gunshot or knife lesion that are submitted to CT scanning, EP must be considered [13].

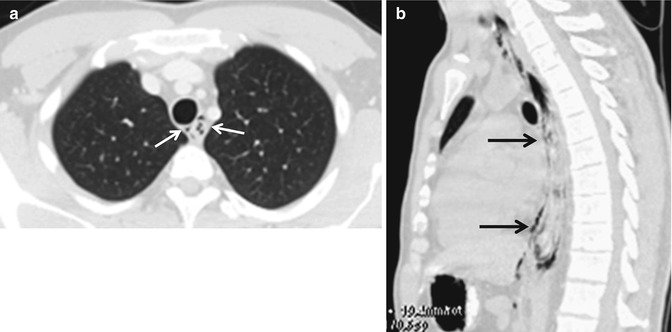

Fig. 4.5

(a, b) Esophageal parietal pneumatosis after foreign body ingestion: (a) white arrows; (b) black arrows

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree