13 Esophagus, Stomach, Duodenum Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an extremely valuable tool for the local staging of various types of gastrointestinal tumor. Initial enthusiastic reports on the technique’s diagnostic value were later qualified, but EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has extended the method’s range of applications. Wall Layers in the Esophagus, Stomach, and Duodenum The accuracy of EUS measurement of the thickness of the gastrointestinal wall depends on physiological peristalsis; a contracted segment can resemble a thickened intestinal wall. Published studies provide some reference values for the “normal” thickness of the gastrointestinal wall, but these tend to have a wide range due to the use of different examination techniques (e.g., more or less application pressure) and technical parameters (such as the frequency used and the accuracy of measurement), and in addition there is considerable interobserver variability. As in conventional transabdominal ultrasound of the bowel, EUS can delineate five layers in the wall of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (Table 13.1). In the esophagus, the muscularis propria can be divided into a hypoechoic inner layer (ring) and a hypoechoic outer layer (longitudinal). A hyperechoic connective-tissue layer can be detected between these two layers of muscle (Fig. 13.1, Table 13.1). Further differentiation of the mucosa is possible in some cases, but is of less clinical significance. Although acoustic changes in the impedance cannot in principle be equated with the histological structure of the intestinal wall, the endosonographic image of the layers can provide orientation. Edema, cellular infiltration, cicatricial changes, and neoplastic masses can produce an endosonographic image of a thickened intestinal wall. Hypoechoic parts of the intestinal wall predominate when there are active inflammatory processes. However, echogenicity alone is not a sufficient marker of inflammatory activity. In addition, echogenicity may be biased by the frequency of the transducer used. Mucosal edema with normal or slightly reduced peristalsis can lead to accentuated intestinal layers. By contrast, the typical layers of the intestinal wall can be disrupted by invasive processes (such as neoplasms and lymphomas) (Figs. 13.2 and 13.3).

EUS morphology of the intestinal wall | Interpretation |

Hyperechoic (echo-rich) inner layer | Physical entrance echo (transition between the lumen and the mucosa) |

Hypoechoic (echo-poor) inner layer | Mucosa |

Hyperechoic middle layer | Submucosa |

Hypoechoic outer layer | Muscularis propria |

Hyperechoic outer layer | Physical emission echo (serosa, adventitia/surroundings) |

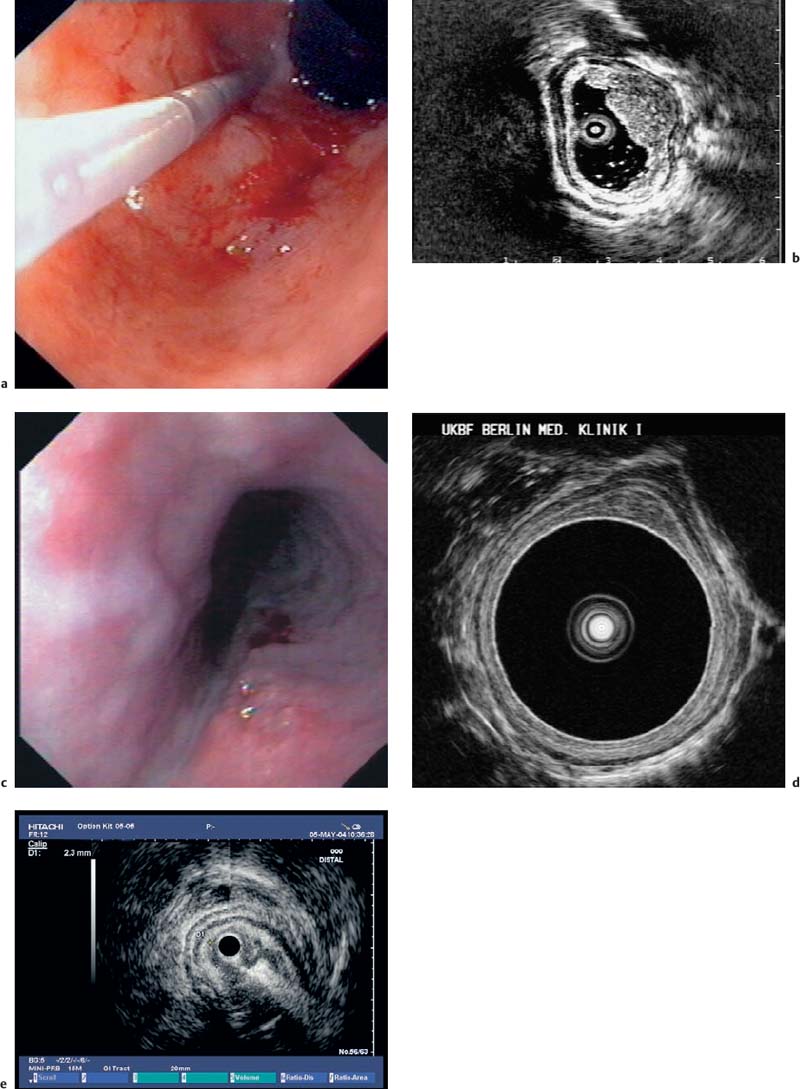

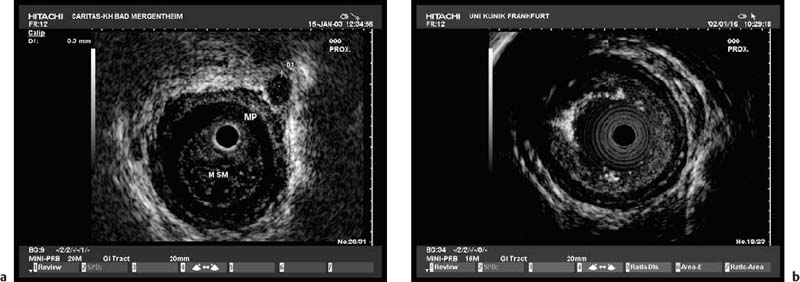

Fig. 13.1a, b The layers of the esophageal wall. a Normal esophageal layers, showing the mucosa (M) and submucosa (SM; not clearly defined here), as well as the muscularis propria (MP). A small normal periesophageal lymph node is indicated between the markers.

b The inner (ring) muscular layer and outer (longitudinal) muscular layer are circumscribed.

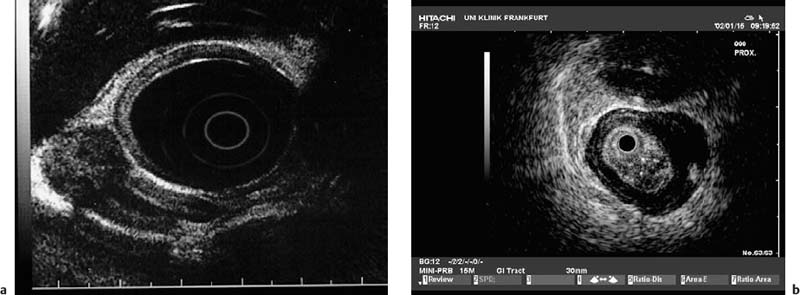

Fig. 13.2 Disrupted layers of the esophageal wall in a patient with a mucosal tear. This type of mucosal tear, as well as a conventional biopsy, can lead to intramural bleeding or edema, with considerable changes in the layers that prevent adequate endosonographic assessment.

Fig. 13.3 Disrupted layers of the esophageal wall after radiotherapy. Due to a variety of changes, and particularly as a result of fusion of the anatomical layers, re-staging with EUS after radiotherapy is not reliably possible.

Thorough anatomical knowledge of the abdominal and thoracic region, familiarity with different imaging qualities (e.g., radial or linear EUS and the effects of the angle of the acoustic level relative to the tip of the EUS probe), a feeling for the position of the probe tip, and a strong three-dimensional spatial sense are necessary for correct anatomical classification of findings in the intestinal wall. In addition to having good endoscopic skills and familiarity with ultrasound, examiners have to go through an extensive learning process to be able to grasp the different and variable acoustic levels in EUS. Basically, the gastrointestinal tract and the adjacent organs can be examined at the horizontal, sagittal, frontal, and subsequently at mixed and variable levels. With the radial EUS scanners currently available, the acoustic level that is mapped is pivotable in a user-defined way. This means that different views from cranial and caudal can be obtained without moving the probe tip.

Older EUS devices (e.g., the Olympus UM-3 generation) only had two settings. However, these systems already had remarkable spatial resolution. In addition to anatomical knowledge and a basic understanding of the special imaging view provided by EUS devices, observing specific conventions during the course of an examination is useful for maintaining continuous anatomical orientation. In the ideal case, the EUS device can be passed through the gastrointestinal tract with only ultrasound and manual guidance, without endoscopic viewing. Rotating the stem of the EUS device produces comparable rotation of the EUS image, so that optional imaging positions can be achieved. In EUS, the esophagus is usually examined with the spine at the 6-o’clock position and the patient’s left side at the 3-o’clock position. This approach facilitates comparison with other imaging modalities (such as computed tomography). However, other different approaches are also used.

Filling the organ with water and/or using a water-filled balloon at the tip of the EUS device can help provide a better view. Starting in the distal part of the esophagus, water filling can be carried out to improve the imaging quality. Filling the balloon slightly after inserting the scope can help prevent mucosal damage by smoothing the potentially traumatic tip of the device. Water filling of the lumen is contraindicated in the proximal part of the esophagus, due to the risk of aspiration.

EUS is indicated for staging malignant tumors in patients with no distant metastases, and for clarifying unclear findings. Endosonographic assessment of the esophageal wall is the method of choice and provides unrivaled resolution (Fig. 13.1).

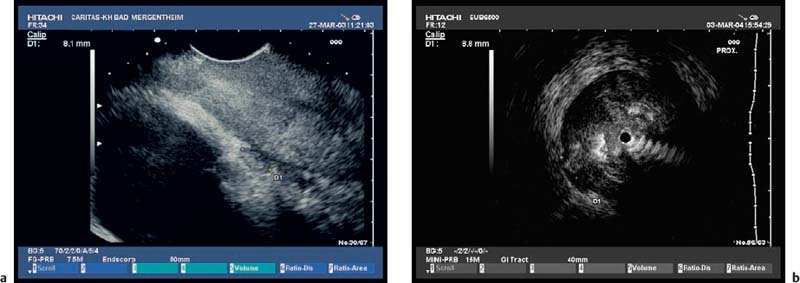

Fig. 13.4a, b A leiomyoma is visible in the outer muscular layer on radial EUS (a) and with the miniprobe (b).

Fig. 13.5 Lipoma. EUS demonstration of a lipoma, achieved by assigning the submucosa as the underlying anatomic layer. The echogenicity depends on the size of the fat droplets and the EUS frequency used. Lipomas may be hypoechoic but are more often hyperechoic or mixed.

The value of EUS in histologically confirmed benign diseases of the esophagus is unclear. There have been no large prospective studies on the clinical impact of EUS in benign esophageal diseases. Depending on the presence of Barrett’s epithelium, differences in the thickness of the esophageal wall can be measured endosonographically, but as these lie in a range of less than 1 mm they have not become clinically relevant. However, EUS is helpful for clarifying submucosal lesions and assessing impressions on the esophageal wall. EUS can distinguish between mesenchymal tumors, which are often encountered—e.g., leiomyoma (Fig. 13.4), fibroma, lipoma (Fig. 13.5), hemangioma, myxoma—and rare epithelial tumors (such as cysts and papillomas). The symptoms of the various lesions are not characteristic; the principal symptom is dysphagia. Before endoscopic resection of such tumors, vessels need to be excluded as the cause of mucosal or submucosal swelling to avoid fatal complications.

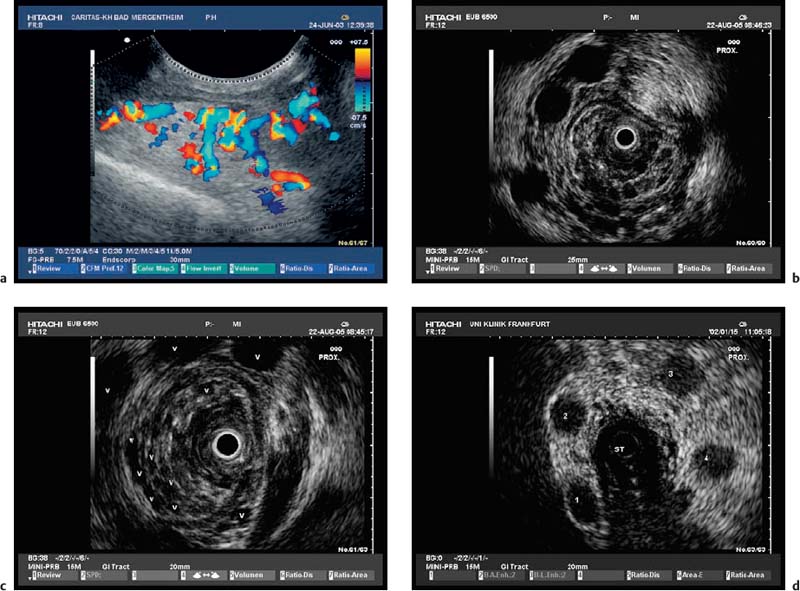

The success of treatment for esophageal varices is assessed endoscopically. Conventional EUS can provide adequate assessment of intraluminal and extramural varices that are not endoscopically visible, but the management implications of this are not clear (Fig. 13.6).

Malignant Tumors of the Esophagus

Malignant Tumors of the Esophagus

Malignant intratumoral and extramural tumor growth can normally be evaluated very well with EUS. However, tumor-related esophageal stenoses that prevent passage of the endoscope are problematic, since in these cases the transverse acoustic level leads to overestimation of the extent of the tumor.

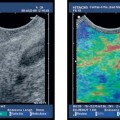

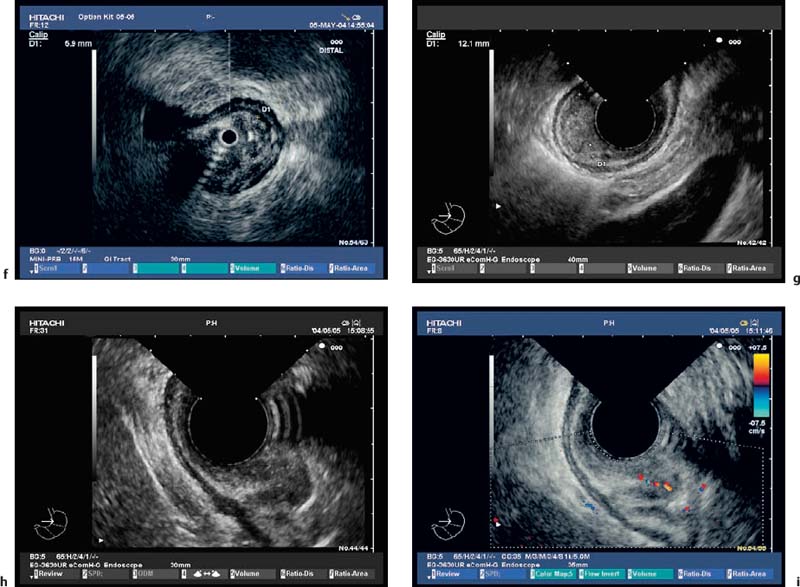

Some studies have shown that small T1 esophageal carcinomas cannot be definitely assigned to the mucosa or submucosa using conventional EUS, which is in contrast to our own experience. However, the distinction is essential for assessing whether endoscopic mucosal resection of these small tumors is possible. Whether a T1 carcinoma has only infiltrated the mucosa or has already penetrated into the submucosa has substantial prognostic relevance. In patients with submucosal tumor invasion, and depending on the depth of submucosal infiltration, the rate of lymph-node metastases is much higher in comparison with those who only have mucosal invasion. T1 tumors with submucosal invasion are there fore not suitable for primary endoscopic therapy. Clear differentiation between T2 and T3 esophageal carcinomas is also challenging in relation to the prognosis and surgical strategy. Peritumoral edema or inflammatory infiltration, or both, can give tumors a hypoechoic margin that is difficult to distinguish from the tumor itself. Elastography may be helpful for differentiating between soft inflammatory tissue and harder neoplastic infiltration. The malignant status of circumscribed esophageal lesions can only be assessed with histological examination of representative biopsies (as the gold standard). Attempts have been made to develop EUS criteria for malignancy, but the initial cancer diagnosis in the gastrointestinal tract is always established using a histological examination of endoscopic biopsies.

Fig. 13.6a–d Esophageal varices. Conventional EUS with color Doppler is helpful for identifying submucosal or extramural esophageal varices (a). Esophageal varices can also be detected with miniprobe EUS, demonstrating extramural vessels (a, b), intramucosal varices (c), and thrombosed vessels after therapy (d). ST, stomach.

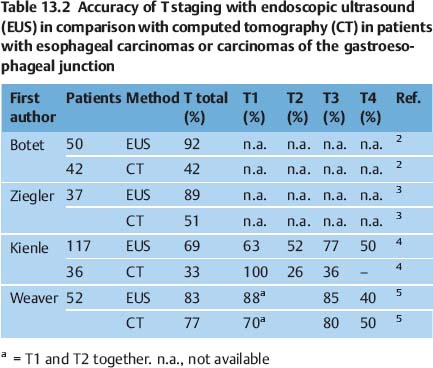

Operability is the deciding criterion in the assessment of malignant esophageal tumors. The reported accuracy of EUS for assessing the extent of tumors (T staging) is 80–90%, slightly higher than that in the stomach. EUS examination of the esophagus is an established diagnostic method that still provides the only way of distinguishing between the different layers of the esophageal wall.

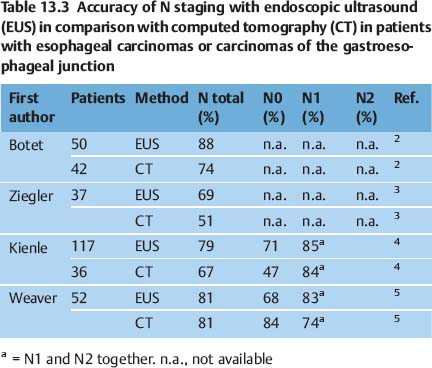

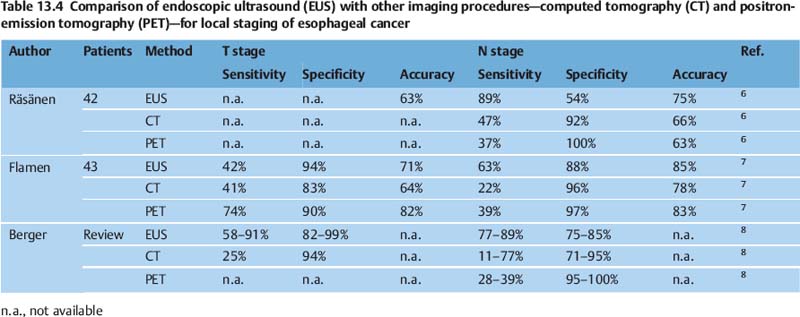

Several publications have shown that EUS is superior not only to computed tomography (CT) but also to more recent imaging techniques such as positron-emission tomography (PET) (Tables 13.2, 13.3 and 13.4). CT of the chest and magnetic resonance imaging have a sensitivity of only around 40–60% for mediastinal lymph-node involvement; however, studies do vary. For mediastinal lymphnode involvement, thoracoscopic procedures for tissue biopsy carry a risk of complications in up to 35% of cases. PET has been shown to be beneficial for detecting metastatic disease; however, the detection rate for locoregional metastases is limited. A meta-analysis was recently conducted to examine the role of EUS in the staging of esophageal cancer for locoregional spread.1

The sensitivity of EUS for T staging in esophageal carcinoma is 85–95%. However, there is some variation in the accuracy depending on the specific T stage.

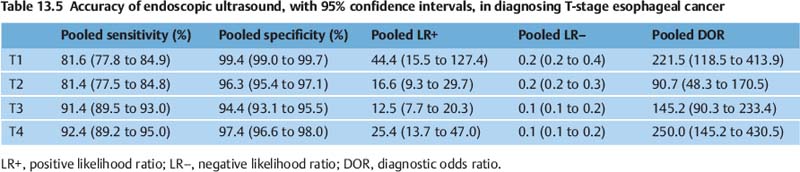

In the meta-analysis mentioned above, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of EUS for diagnosing T1 cancer were 81.6% (95% CI, 77.8 to 84.9) and 99.4% (95% CI, 99.0 to 99.7), respectively. For T2 staging, EUS had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 81.4%(95% CI, 77.5 to 84.8) and 96.3% (95% CI, 95.4 to 97.1), respectively. For T3 staging, EUS had a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 91.4% (95% CI, 89.5 to 93.0) and 94.4% (95% CI, 93.1 to 95.5), respectively. For diagnosing T4 cancer, EUS had a pooled sensitivity of 92.4% (95% CI, 89.2 to 95.0) and specificity of 97.4% (95% CI, 96.6 to 98.0). Table 13.5 shows the pooled accuracy estimates of EUS for T staging in esophageal cancer.1

In addition, as EUS is not capable of differentiating between tumor infiltration and concomitant inflammatory reactions, over staging on EUS continues to be a problem (Figs. 13.7, 13.8, 13.9, 13.10, 13.11 and 13.12).

Studies have shown that EUS has a sensitivity of 70–80% for N staging in esophageal carcinoma.

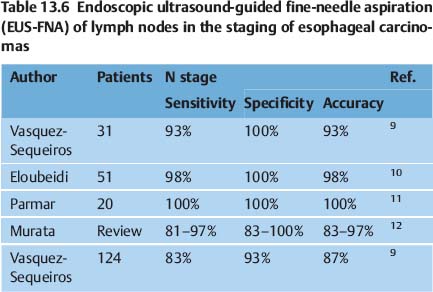

EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) can improve the results in the staging of esophageal carcinomas, as has been shown by several reports comparing the method with CT and with conventional EUS without FNA (Tables 13.6 and 13.7).

With FNA, the sensitivity of EUS for diagnosing N-stage cancer improved from 84.7% (95% CI, 82.9 to 86.4) to 96.7% (95% CI, 92.4 to 98.9). The specificity of EUS improved from 84.6% (95% CI, 83.2 to 85.9) to 95.5% (95% CI, 91.0 to 98.2) with FNA. The accuracy estimates for EUS alone and EUS with FNA are shown in Table 13.8.

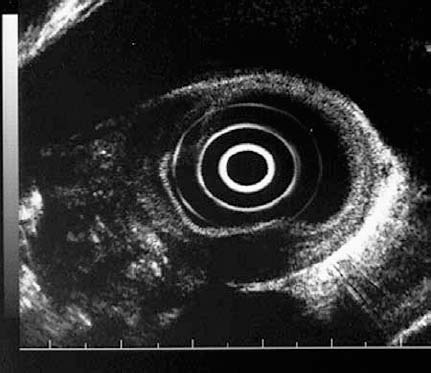

Fig. 13.7a–i T1 esophageal cancer, with mucosal and submucosal invasion.

a-d Ideally, the EUS miniprobe should be used under endoscopic vision without pressure. The EUS miniprobe provides unrivaled optical resolution.

e-g Other forms of T1 m (e) and T1sm tumors (f, g) are also shown. The morphology depends on the inflammatory reaction.

Fig. 13.8 EUS miniprobe findings in T2 esophageal cancer, with invasion of the submucosal (SM) and muscular layers (T2). In this case, the different depth of invasion is very well demonstrated. R, internal (ring) muscular layer; L, external (longitudinal) muscular layer. Due to the limited acoustic penetration with EUS miniprobes, adequate staging of periesophageal lymph nodes is not possible.

Fig. 13.9 T2 N1 esophageal carcinoma. Due to the limited acoustic penetration of EUS miniprobes, adequate staging of periesophageal lymph nodes is not possible. Conventional EUS is therefore recommended for periesophageal lymph-node staging (as in the 4-mm periesophageal lymph node shown here). Conventional EUS also allows EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of lymph nodes, particularly for assessment of celiac lymph-node metastases.

Fig. 13.10a, b T3 esophageal carcinoma. Tumor invasion into the periesophageal connective tissue can be detected reliably with conventional EUS (a, between the marks), as well as with the EUS miniprobe (b, between the marks). Inflammatory reactions and atypical vessels affecting the T3 stage need to be taken into consideration.

Fig. 13.11 T4 esophageal carcinoma. The T4 stage of esophageal carcinoma is defined as infiltration of the mediastinal vessels (such as the aorta, in this case) or infiltration of the heart.

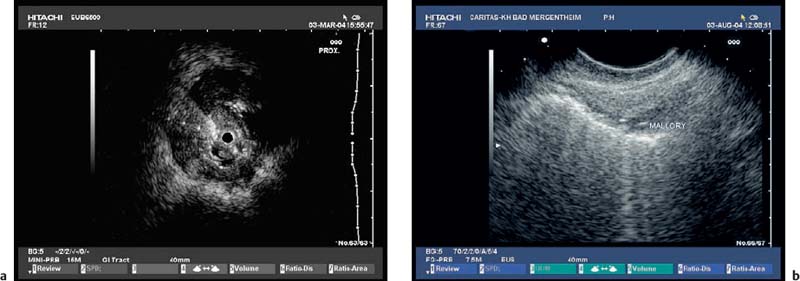

Fig. 13.12a, b EUS staging after dilation.

a Due to intramural bleeding and edema, EUS staging after dilation of malignant esophageal stenoses is not reliable, leading to an over-staging, as seen in this case in a patient with a T2 carcinoma.

b In a patient with a Mallory-Weiss lesion, air echoes are seen deep in the esophageal wall, showing that EUS staging is only of value in patients with histologically confirmed malignancies.

EUS studies were grouped into three periods in order to standardize changes in EUS technology and changes in EUS criteria for tumor staging: 1986–1994, 1995–1999, and 2000–2006.1 The pooled estimates of studies during these periods are shown in Table 13.9.

EUS as an imaging modality has high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing N-stage esophageal cancer. This meta-analysis shows that FNA substantially improves the sensitivity (85–97%) and specificity (85–96%) of EUS for evaluating N-stage esophageal cancer. EUS with FNA should therefore be the diagnostic test of choice.

During the last 20 years, the specificity of EUS for diagnosing T-stage cancer has remained high. The method’s sensitivity for T staging has also improved, particularly for early disease (T1), during the last 20 years, possibly due to improvements in imaging technology or training. For nodal staging, all the studies in which FNA was performed were from the most recent periods. The sensitivity and specificity of EUS alone for diagnosing N-stage cancer has not improved during the last 20 years. The meta-analysis shows that the sensitivity and specificity of EUS markedly improved with FNA.1

In summary, EUS has excellent sensitivity and specificity for accurately diagnosing T-stage esophageal cancer. EUS performs better with advanced (T4) than early (T1) disease. FNA substantially improves the sensitivity and specificity of EUS in evaluating N-stage esophageal cancers. EUS should be the test of choice for TN staging of esophageal cancer.

The accuracy of re-staging with EUS after chemoradiotherapy for esophageal and gastric tumors is currently a matter of controversy. After chemoradiotherapy, inflammatory and cicatricial processes cannot be distinguished from malignant infiltration, and routine EUS after radiotherapy is not at present accepted. However, local tumor recurrence in the anastomotic region after adequate previous surgery is an exception to this. As in primary tumor staging, local tumor recurrences also have to be confirmed histologically. Due to the underlying inflammatory and cicatricial changes, EUS of suspected local tumor recurrences has a relatively high level of sensitivity, but with low specificity.

| EUS | EUS-FNA |

Studies | 44 | 4 |

Pooled sensitivity (%) | 84.7 (82.9 to 86.4) | 96.7 (92.4 to 98.9) |

Pooled specificity (%) |

Orientation

Orientation Optimizing the Examination

Optimizing the Examination Indications

Indications

Benign Diseases

Benign Diseases

T Stage

T Stage

N Stage

N Stage