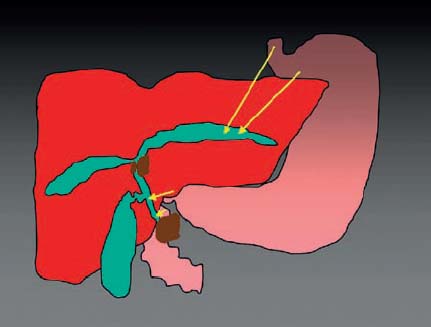

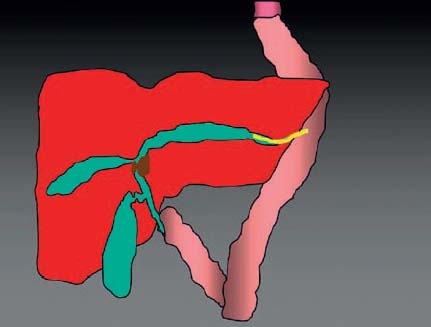

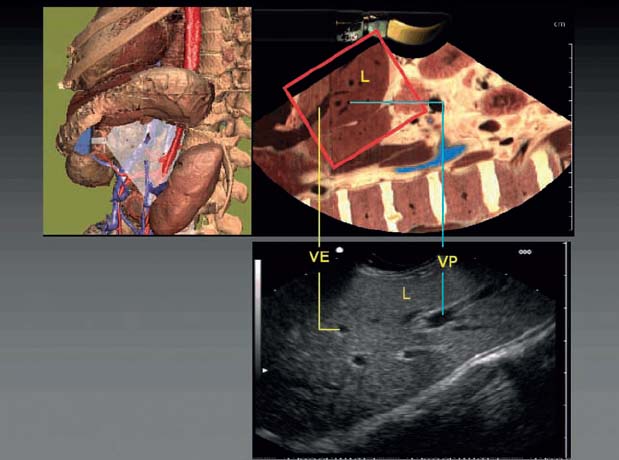

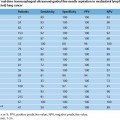

31 EUS-Guided Biliary Drainage Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) with stenting of the bile duct is a well-established procedure for palliative treatment of malignant pancreaticobiliary strictures.1,2 In 5–10% of cases, it is not possible to obtain access to the bile duct and place a stent, due to previous surgical procedures such as gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y anastomosis, Billroth II surgery, or Whipple resection. Other reasons may include failed bile duct cannulation, infiltrations of the papilla of Vater, complete stenosis of the common bile duct, obstruction of the pylorus or duodenum in tumor infiltration, and anatomic variations such as upside-down stomach. When ERCP fails, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) has so far been the alternative method and is successful in 90% of the patients.3–6 However, PTBD can be associated with complications such as bleeding, peritonitis, cholangitis, infections, hemobilia, and injuries to the adjacent lung and pleura. If subsequent internal drainage fails, it leads to a significant impairment of quality of life, and the patient has to accept long-term external biliary drainage. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided internal biliary drainage is a potential alternative in these cases. As in other EUS-guided interventions, use of a therapeutic linear echoendoscope with a working channel of 3.7–3.8 mm and an Albarran is strongly recommended in EUS-guided biliary drainage (e.g., Hitachi EG-3870-UTK, EG3830-UT, Olympus GF-UCT140-AL5, Fujinon EG-53 0UT). The procedure is carried out under endosonographic and fluoroscopic control. Administering prophylactic antibiotics reduces the risk of cholangitis, especially if the procedure fails. The access route to the bile duct system depends on the anatomy: • Normal anatomy or Billroth I resection: common bile duct or left hepatic duct (Fig. 31.1) • Billroth II resection or gastrectomy: left hepatic duct (Fig. 31.2) The technical success of the procedure is greater if the shortest route to the dilated duct is chosen; the water-filled balloon on the transducer can sometimes be used to stabilize the position of the device after needle puncture. In normal anatomy or after Billroth I resections, the transducer can be placed either at the level of the cardia for the left hepatic duct or in the duodenum for the common bile duct, depending on the site of infiltration. In Billroth II anatomy, transgastric EUS, or in cases of gastrectomy transjejunal EUS, provides excellent imaging of the dilated intrahepatic ducts in the left liver lobe in patients with biliary obstruction (Figs. 31.3 and 31.4). The EUS transducer has to be placed at the level of the cardia. Fig. 31.1 Normal anatomy, showing possible access routes for EUS-guided biliary drainage (arrows). Fig. 31.2 A possible access route for EUS-guided biliary drainage following gastrectomy. Fig. 31.3 EUS meets Voxel-MAN. The transducer is directed toward the left liver lobe (L), with visualization of the portal vein (VP) and hepatic veins (VE). Fig. 31.4 EUS, showing dilation of the left intrahepatic bile duct. Fig. 31.5 Color Doppler, showing a dilated left intrahepatic ductand the portal vein. Fig. 31.6 EUS: puncture of the bile duct with a 19-gauge needle. To reduce the risk of bleeding, puncture should be carried out with color Doppler ultrasound imaging in order to avoid interposed vessels (Fig. 31.5). A 19-gauge aspiration needle (EchoTip Ultra Echo-19, Wilson-Cook; EZ Shot 19 G, Olympus Medical) is inserted into the dilated bile duct through the gastric or intestinal wall (Fig. 31.6). After removal of the stylet and bile aspiration, contrast medium is injected to obtain a cholangiogram (Fig. 31.7). Particularly in patients with Klatskin tumors, complete imaging of the intrahepatic ducts is necessary in order to obtain information about the location of the stenosis or occlusion, the length of the stenosis, the involvement of both ducts, or whether it is possible to reach the duodenum via a guide wire. Fig. 31.7 Fluoroscopy: puncture of the left hepatic duct. Fig. 31.8 EUS, showing an inserted guide wire. A 0.035-inch guide wire is inserted into the bile duct via the needle (Hydra Jagwire 0.035, Boston Scientific; Tracer Metro Guide 0.035 inch, Cook-Medical; Nitinol 0.035, MTW). To reduce the risk of wire dislocation, it is recommended to insert as much as possible of the wire into the duct (Figs. 31.8 and 31.9). In patients with normal anatomy or Billroth I resection, an attempt should always be made to pass the guide wire into the duodenum across the biliary stricture, with subsequent rendezvous ERCP drainage. In all other cases, the wire is placed at the level of the bile duct bifurcation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree