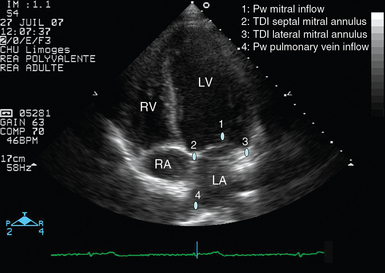

34 Weaning failure is a major complication of mechanical ventilation with associated morbidity and mortality. It is usually defined as an unsuccessful spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) or need for tracheal reintubation within 48 hours following extubation.1 According to study populations and diagnostic criteria, the incidence of weaning failure ranges from 25% to 42% in large cohorts.1 Although the mechanisms are varied and potentially complex, failure to wean a critically ill patient from the ventilator frequently has a cardiac origin. Indeed, the transition from positive-pressure ventilation to spontaneous breathing abruptly alters cardiac loading conditions and has been compared with an exercise test that increases cardiac and breathing workload and metabolic expenditure.2 Accordingly, patients at high risk for weaning failure have long been identified as those with cardiovascular disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).3,4 Since transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is usually informative in this specific clinical setting, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is rarely required and performed only as an adjunct to TTE in a patient reconnected to the ventilator. The apical four-chamber view is mainly used to obtain the requested information because it allows evaluation of global and regional ventricular systolic function, left ventricular (LV) diastolic properties and filling pressure, valvular function, intraventricular pressure gradient, and systolic pulmonary artery pressure (Figure 34-1). Figure 34-1 Apical four-chamber view disclosing the positioning of pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler imaging samples for assessment of left ventricular filling pressure (blue dots). In addition, this transthoracic echocardiographic view allows evaluation of ventricular function and identification of mitral or tricuspid regurgitations via color Doppler mapping and continuous wave Doppler. LA, Left atrium; LV, left ventricle; Pw, pulsed wave Doppler; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; TDI, tissue Doppler imaging. Interestingly, TTE may be combined with chest ultrasound to best guide the diagnostic workup of patients with weaning failure at the bedside. After completion of TTE, chest ultrasonography can be performed to obtain valuable morphologic information on the lungs and pleurae, both of which are potentially involved in the weaning failure. For example, chest ultrasonography allows a quantitative diagnosis of pleural effusion and helps in deciding whether to perform thoracentesis in hypoxemic ICU patients.5 The transition from positive-pressure ventilation to spontaneous breathing abruptly increases ventricular preload and LV afterload, decreases effective LV compliance,3 and may even induce cardiac ischemia.6 All these factors tend to increase LV filling pressure, which may result in weaning-induced cardiogenic pulmonary edema, especially in patients with left-sided heart disease.7 Nevertheless, in the absence of left heart failure (e.g., COPD patients), the rise in pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP) remains limited.8 In 117 ICU patients fulfilling the criteria for weaning, we performed TTE immediately before and at the end of a 30-minute SBT. The SBT significantly increased LV stroke volume (and hence cardiac output) and LV filling pressure over baseline values as reflected by a higher mitral Doppler E/A ratio and shortened E-wave deceleration time.9 Similarly, Ait-Ouffela et al10 showed that SBTs increase the mitral E/A ratio and shorten the E-wave deceleration time. We previously showed that ICU patients who failed ventilator weaning had a significantly lower LV ejection fraction (median [25th to 75th percentiles]: 36% [27% to 55%] vs. 51% [43% to 55%], P = .04) and higher LV filling pressure (E/E′ ratio: 7.0 [5.0 to 9.2] vs. 5.6 [5.2 to 6.3]; P = .04) before the SBT than did patients who were successfully extubated.9 Papanikolaou et al11 reported that a lateral E/E′ ratio higher than 7.8 at baseline (pressure-support ventilation) predicted SBT failure in 50 ventilated ICU patients with a sensitivity and specificity of 79% and 100%, respectively. Cardiogenic pulmonary edema induced by weaning from the ventilator is suspected in high-risk patients when alternative causes of weaning failure have been confidently ruled out.7 It is a leading cause of weaning failure. In a TTE study performed in 117 ventilated ICU patients, we showed that weaning failure was of cardiac origin in 20 of 23 patients (87%) with an unsuccessful SBT or extubation.9 In patients in whom weaning-induced pulmonary edema develops, echocardiography depicts the presence of increased LV filling pressure and helps identify the potential underlying cause to guide therapy. Using right-heart catheterization, Lemaire et al3 have long reported that patients in whom weaning-induced pulmonary edema developed exhibited a marked increase in PAOP from a mean value of 8 mm Hg to 25 mm Hg after disconnection from the ventilator. TTE diagnosis of pulmonary edema induced by weaning relies on depiction of elevated LV filling pressure during spontaneous breathing by means of mitral inflow and pulmonary vein Doppler velocity profiles (Figure 34-2

Evaluation of patients at high risk for weaning failure with doppler echocardiography

(CONSULTANT LEVEL EXAMINATION)

Overview

Echocardiographic examination

Hemodynamic changes induced by spontaneous breathing trials

Identification of patients at high risk for pulmonary edema during weaning

Identification of pulmonary edema during weaning

Identification of elevated left ventricular filling pressure

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Evaluation of patients at high risk for weaning failure with doppler echocardiography: (CONSULTANT LEVEL EXAMINATION)