21 Extremity Venous Anatomy and Technique for Ultrasound Examination

The three main goals in diagnosing venous thrombosis are to determine the following:

1. The presence or absence of thrombus

2. The relative risk for the thrombus dislodging and traveling to the lungs

Venous duplex is uniquely suited for each of these tasks.

In order to perform venous duplex ultrasound of the veins, the examiner must understand the venous anatomy1–4 and be fully acquainted with the examination protocols for imaging the veins. In this chapter we will review the venous anatomy and the examination protocols.

Anatomy of the Lower Extremity

There are three kinds of veins that will be examined by duplex imaging:

Superficial Veins

There is a mistaken idea that clots within the superficial veins pose no threat of producing a pulmonary embolism. Clots can and do break loose from superficial veins and travel to the pulmonary arteries. These clots in the superficial system are less likely to cause major, clinically significant pulmonary embolism because they are usually smaller than clots found in the deep veins, and they are less likely to be dislodged because they are not surrounded by muscle. Examination of the superficial veins is still an important part of a complete evaluation of the lower extremity because superficial clots may become large (as the normally small superficial vein is expanded by the contained thrombus) and cause considerable discomfort. There is also potential danger that a superficial vein clot can extend into the deep system.

Venous Duplex Imaging Examination Technique and Protocol

Patient Positioning for the Lower Extremity

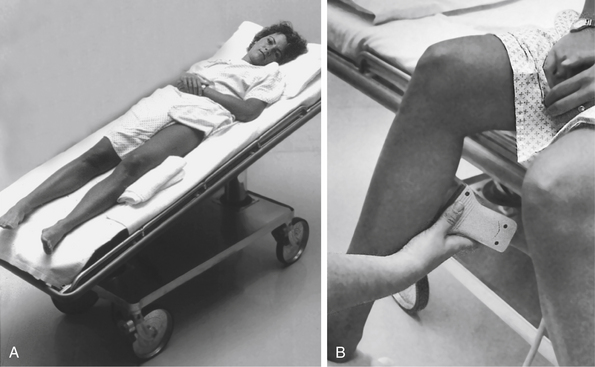

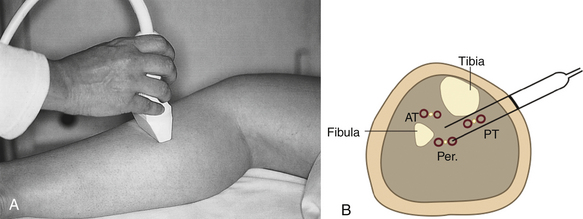

When imaging the lower extremity, the bed should be tilted to allow blood to dilate the leg veins so they can be imaged clearly. Omitting this seemingly insignificant step is one of the most common reasons for missing small clots, especially in the calf. The bed should be placed in a reversed Trendelenburg’s position (head elevated) at about 20 degrees (Figure 21-1, A). Another technique to distend the calf veins is to allow the patient to sit up during calf evaluation (Figure 21-1, B). This is extremely effective but is clumsy and can make the veins difficult to compress. In this situation, veins filled with stagnant flow may be mistaken for thrombus-filled veins.

After the bed is tilted, the patient must be positioned properly. For the lower extremity, this means having the knee slightly bent and the hip externally rotated (Figure 21-2). This allows full access to the medial portion of the thigh and calf and also allows access to the popliteal fossa. Trying to image the leg without proper positioning will lead to inadequate views and errors in diagnosis.

Patient Positioning for the Upper Extremity

The upper extremity veins are examined with the bed flat and the patient in the supine position. It is especially important that the bed be flat while the jugular and subclavian veins are examined because they will collapse if the head of the bed is up. Once these vessels are imaged, the bed can be raised to allow for imaging of the arm veins. The arm is positioned at the patient’s side for examination of the neck veins and the subclavian vein. When examining the axillary veins, the arm is repositioned with the arm raised to allow access to the axilla. It is repositioned again in a slightly lower position with the arm externally rotated to allow access to the medial portion of the upper and lower arm.

Proper Technique and Diagnostic Criteria

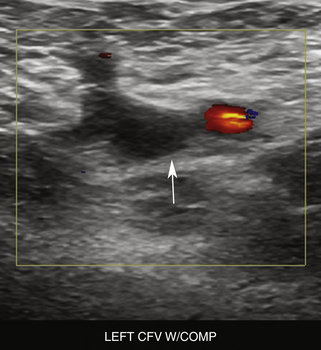

Before the 1980s, venograms were the only method available for looking inside the veins of the extremities. It was thought that ultrasound would not be useful in imaging the veins because clots were thought to be invisible to ultrasound (this was the so-called wisdom of the experts of the day). Despite this false assumption, attempts to image the veins with ultrasound began in the early 1980s. In attempting to find diagnostic criteria for identifying clots, investigators discovered not only that you actually could see clot on ultrasound, but also that normal veins are so easily compressed with light probe pressure that vein compression could be used to unequivocally determine the absence of thrombus in that vein.5 Defining compression of the vein as the primary criterion for duplex imaging for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) was the major factor in its universal acceptance. Using compression in this way allows for the examination to quickly progress in a transverse plane to evaluate the extensive venous anatomy.6–10

Imaging Normal, Thrombus-Free Veins

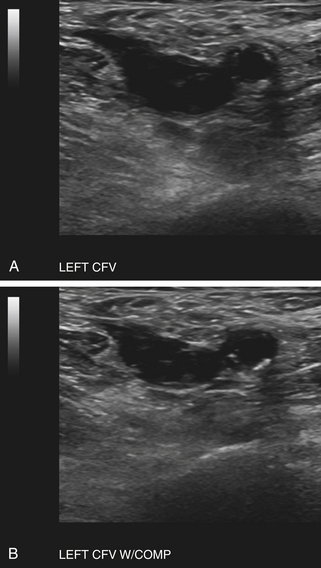

If the vein is thrombus-free, it will compress completely so that the inner vein walls actually touch each other. When the vein collapses completely with light probe pressure, it can be determined to be unequivocally thrombus-free at that location (Figure 21-3). This is the key to venous duplex imaging of the veins. The pressure on the vein is released, and the vein will reopen. The examiner then moves the probe along the length of the vessel, compressing every centimeter or so, until the entire vein has been imaged in this way. It is important to ensure that these compression maneuvers are as close together as possible. If the “cuts” are too far apart, a major section of vein containing thrombus can be missed. As a rule, the smaller the cuts, the less chance there is of missing a thrombus.

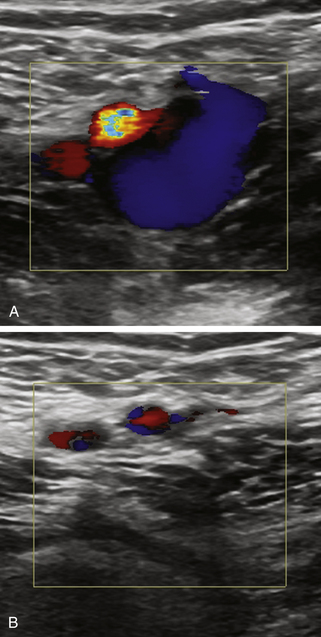

After the entire segment of vein has been evaluated in the transverse plane, the examiner can rotate the probe and rescan the segment in the longitudinal plane and add color and pulsed Doppler (Figure 21-4). These views provide additional information regarding blood flow through the venous system. These longitudinal views, however, are only an addition to the information already gathered by the transverse compression views and cannot substitute for them. Substituting longitudinal views with color Doppler for the transverse compression views will result in missing partially obstructive thrombus.

Color and Doppler Information Added to Transverse Compression Views

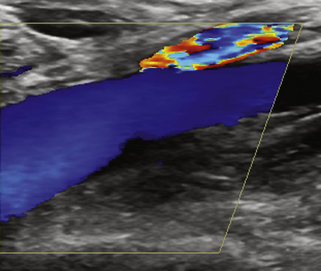

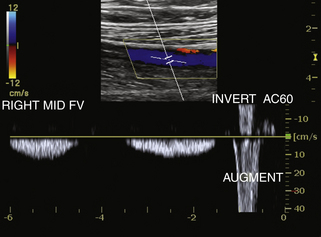

Present accreditation protocols require transverse compression views and longitudinal views with color and pulsed Doppler information to be performed at specific levels. Doppler signals in the normal leg vein will be phasic (suggesting an absence of obstruction of the major veins above the level of the probe). The flow in the vein should stop completely as the patient takes a breath in and should resume spontaneously as the patient exhales. Squeezing of the leg distal to the level of the transducer should produce an augmentation of flow during this maneuver (Figure 21–5). This indicates the lack of an obstruction of the major veins from the level of the squeeze to the level of the transducer. The examiner must understand the limitations of information gathered by pulsed or color Doppler; a partially obstructive thrombus may be missed using these methods—thus the need for the transverse compressions.

Determining the Presence of Thrombus

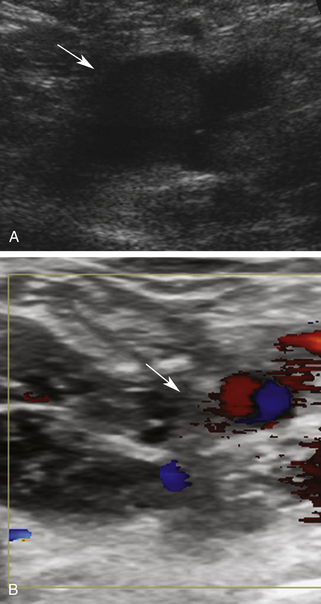

Thrombus is present within the vein when echogenic material is identified within the lumen of the vein (Figure 21-6) and when full compression of the vein is impeded. It is crucial to note that both of these things must occur together to definitively make the diagnosis of thrombus in the vein (Figure 21-7). Too many institutions simply look for noncompressibility of the vein (some institutions refer to duplex venous imaging as “compression ultrasound”). Failure to link these two will result in false-positive results in cases where the veins are difficult to compress—not because of the presence of thrombus—but because of a myriad of other factors. For example, proximal compression of the vein causing stagnation and increased echogenicity of blood flow may simulate intraluminal thrombus. Complete compression of the vein lumen excludes thrombus (Figure 21-8). Other pitfalls include incomplete compression from a patient bearing down in response to painful probe compressions (Figure 21-9), compression being limited by a nearby bone, and other factors. In the case where the vein is not compressing but thrombus cannot be seen directly (poor views or views of very small or deep structures), an additional maneuver is essential to determine whether the noncompressibility is due to the presence of thrombus or some other factor. This additional maneuver may involve compressing harder until the artery next to the vein starts to compress. If the artery next to the vein compresses and the vein does not, thrombus is likely to be present within the vein despite the fact that the clot is relatively anechoic or is not directly visualized. Augmentation of flow through the noncompressible segment may also demonstrate patency, although this maneuver may not exclude a partially occlusive clot. If there is uncertainty regarding the presence of DVT, a correlative study with magnetic resonance venography or computed tomographic scanning may be required for further evaluation.

Characterization of Thrombus

Characteristics usually associated with chronic clot are the following:

Acute Thrombus

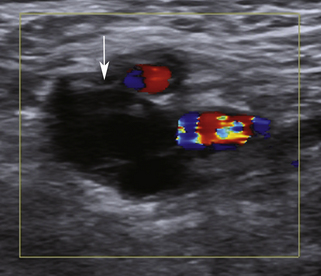

When a thrombus has just formed, it is very faintly echogenic—almost invisible. When the clot is acute, it may be detected by limiting the compression of the vein and by the presence of a faintly visible edge to the thrombus (Figure 21-10). The experienced examiner will spot faint echoes within the vein and note the difficulty in compression (Figure 21-11). Thrombi at this stage are extremely spongy in texture, so the vein will deform with probe compression (but still not allow complete collapse of the vein). Thrombi at this stage of formation may be attached to the vein wall over only a small area with the remainder of the clot looking like a snake that sways back and forth in the flow stream (“free-floating” DVT) (Figure 21-12). The fact that these poorly attached clots might be more likely to break loose seems logical, although this seemingly obvious conclusion is not universally accepted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree