2Barts Health NHS Trust, The London Hospital School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK

3The London Independent Hospital, London, UK

- Up to 70% of RTAs sustain facial injuries, mainly soft tissues. Head and cervical spine injuries must be ruled out before imaging the face

- Understand anatomy and classification of injuries

- Injuries occur mainly to the midface and mandible

- Always look for a second fracture in the mandible

- Plain radiographs are difficult to interpret and provide limited information. There should be a low threshold for use of CT and coned beam CT

The face is often injured in road traffic accidents, fights and assaults. Up to 70% of people who are in road traffic accidents sustain facial injuries, and most of these are soft tissue injuries. Associated injuries occur in up to half of patients with facial fractures, but, surprisingly, only 2% of these associated injuries occur to the cervical spine. The distribution of injuries to the face varies with patient population, but injuries usually occur to the midface or mandible.

Head and cervical spine injury should be excluded before patients are positioned for plain radiographs, in particular to avoid causing secondary neurological injury. Accurate radiological diagnosis is central to the management of maxillofacial trauma and other medical and surgical conditions that affect the facial bones. Although computed tomography (CT), and the more recently introduced cone beam CT (CBCT), is used increasingly in emergency assessment of such patients, plain radiographs play a central role in the initial management.

Plain radiographs are difficult to interpret, findings are subtle and there should be a low threshold for further imaging, in particular thin section MDCT with multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs) and 3D and CBCT. Using a systematic approach with a meticulous technique is essential, in particular studying the air-bone interfaces, cortical continuity, and symmetry helps the non-specialist to assess the facial bones.

- Frontal sinuses—posteroanterior (PA) and lateral

- Orbits including detection of foreign bodies (FBs)—PA20 and occipitomental (OM)

- Midface—OM and OM30

- Nasal bone—none usually or a coned lateral

- Mandible—OPG, PA mandible and lateral oblique

Anatomy

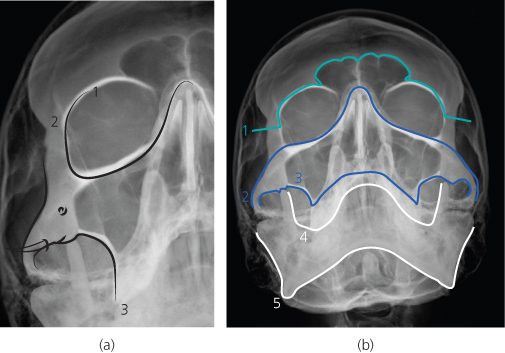

The key to interpretation of imaging of maxillofacial injuries is to understand the basic anatomy and the radiological appearances of the face. The face can be divided into three areas (Figures 9.1 and 9.2):

- Midface (maxilla, zygoma, and nasal bones)

- Upper face (orbit and frontal sinuses)

- Lower face (mandible)

Figure 9.1 Anatomical division of the face into upper, mid and lower regions.

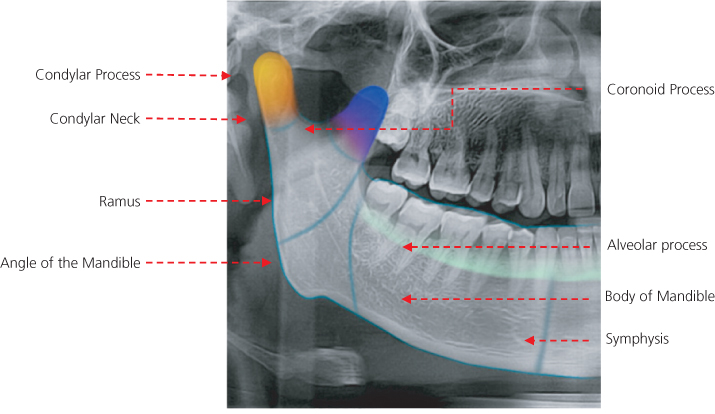

Figure 9.2 Anatomy of the face. 1, frontal bone; 2, frontal sinus; 3, supra orbital rim; 4, orbit; 5, infra-orbital rim; 6, zygomatic frontal suture; 7, maxillary sinus; 8, nasal septum; 9, nasal cavity; 10, zygomatic bone; 11, maxilla; 12, postero-lateral wall of maxillary; 13, zygomatic arch; 14, coronoid process; 15, condylar process; 16, mandible.

ABCs systematic assessment

- Adequacy: choose the correct view and ensure correct positioning and exposure

- Alignment: check Dolan’s lines, McGrigor’s lines, and Campbell’s lines

- Bone: check all the bones in the midface and above and below the midface

- Cartilage and joints: check the zygomaticofrontal sutures and temporomandibular joints

- Sinuses: check for opacification and polyps, and check for the presence of an air-fluid level

- Soft tissues: look for soft tissue swelling and surgical/orbital emphysema. Check for FBs

Adequacy

The standard views are the occipitomental 0° (OM0) and occipitomental 30° (OM30) views. Lateral radiograph for facial injuries is rarely helpful and has been discarded as a routine view. It is important to obtain good quality radiographs in an emergency situation, although this is not always possible because patients can be uncooperative, intoxicated, or unconscious. Additional views may be requested such as a posteroanterior (PA) views to look for injuries of the upper face or to look for radiopaque FBs (in particular glass, debris or metal) and submentovertical (SMV) to look for fractures of the zygomatic arch).

Thin-section MDCT provides exquisite detail of bony and soft tissue injuries and is able to add significant valuable information. MPR and three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions can be done in seconds using relatively low doses.

ABC assessment

The remainder of the ABCs systematic assessment is dealt with under each individual view.

Occipitomental view

This view is simple to acquire and is usually obtained at 0° or 30°. It is able to demonstrate clearly most of the midface. Dolan described three lines that resemble an elephant’s head and trunk.

Figure 9.3 (a) Dolan’s lines representing elephants head with its tusk and trunk; (b) McGrigor’s (1–3) and Campbell’s (4–5) lines.

Figure 9.4 Anatomy of the mandible: 1, condylar process; 2, condylar neck; 3, coronoid process; 4, ramus; 5, alveolar process; 6, angle of the mandible; 7, body of mandible; 8, symphysis.

Several other lines can be used to trace and look for step deformities, radiolucent lines, radio opaque areas and changes of contour. The left and the right sides of each image should be used to compare for symmetry (Figure 9.3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree