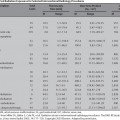

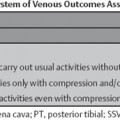

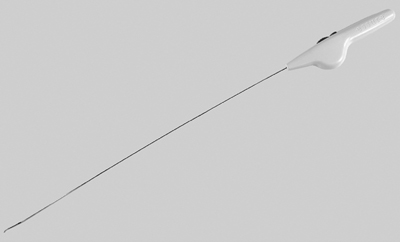

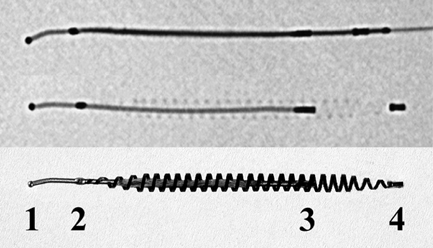

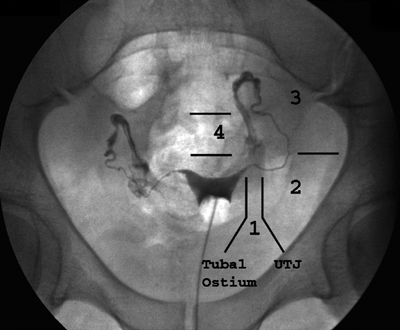

13 Fallopian Tube Occlusion Hugh McSwain and Mark F. Brodie Permanent sterilization, which includes bilateral tubal sterilization (BTS) and vasectomy, is a widely used method of birth control because of its proven safety and effectiveness. An estimated 220 million people worldwide use permanent sterilization for birth control.1 Approximately 10.7 million and 4.2 million American women currently rely on BTS and vasectomy for contraception, which represents 27.7% and 10.9%, respectively, of all contraceptive users in the United States.2 BTS is the most common birth control method in the United States with over 700,000 procedures performed annually. With 500,000 vasectomy patients per year, the estimated annual market in the United States for permanent sterilization is 1.2 million patients. Although both methods of permanent sterilization are effectively equivalent, BTS is more popular despite having greater morbidity.3,4 Over the past 40 years, vasectomy has dropped in popularity relative to BTS; this is possibly due to the increasing safety of tubal ligation.3 A recent development in female sterilization decreases the morbidity of BTS by accessing the fallopian tubes transcervically, thus eliminating the need for laparoscopy and the inherent risks of general anesthesia and the procedure itself.5,6 In November 2002, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for transcervical hysteroscopic placement of the Essure device (Conceptus Inc., Mountain View, CA) for permanent birth control. Fluoroscopic placement of the device is possible and currently performed as an off-label use of the product.7 The first known description of a method for fallopian tube occlusion was written by Blundell and published in 1828.8 The method described bilateral partial salpingectomy with the theoretical result of permanent sterility, but no known attempts by Blundell to perform this procedure were published. Friorep followed in 1849 with his transcervical technique for tubal sterilization.9 This is the earliest documented record of a transcervical method for tubal sterilization (TTS). His method used an application of silver nitrate solution into the proximal fallopian tubes to induce tubal occlusion. Pantaleoni built on the early work of Bozzini and used hysteroscopy as a diagnostic tool in 1869.10 In 1934, Schroeder used hysteroscopy with electrocoagulation on two patients for TTS.11 However, both patients had tubal patency when studied with a follow-up hysterosalpingogram (HSG). Hysteroscopic electrocoagulation for TTS was used in the 1970s with Quinones et al reporting a bilateral tubal occlusion rate of 80%.12 Subsequent work did not reproduce this success and the method fell into disfavor. Concurrent development of female sterilization via abdominal access proceeded in the early 20th century.10 Laparotomy was most commonly used to access the fallopian tubes. Laparoscopic tubal sterilization using electrocoagulation was reported by Boesch in 1936.13 Frangenheim first applied the method of bipolar electrocoagulation for tubal sterilization in 1972;14 today, it is the most common method in the United States for laparoscopic tubal sterilization.15 Other techniques use mechanical devices (e.g., Filshie clip, Falope ring, Hulka clip) to occlude the fallopian tube, which cause less destruction of the fallopian tube and pose no risk of electrical burns. Preserving the maximal amount of tube should always be considered given the possibility that a fallopian tube reconstruction procedure may be desired in the future. Reconstruction procedures are performed when a patient desires to regain her fertility after previous tubal sterilization. Many methods for TTS have been reported in the literature. Though these methods vary greatly in design, the common endpoint is tubal occlusion. This is mediated via mechanical occlusion,16–21 inflammation,22–28 or a combination of the two.5,6,29–34 Thurmond et al performed the initial evaluation of the Essure device in rabbits using hysteroscopy and fluoroscopy during the placement procedure.35 This success led to FDA clinical trials of the device with subsequent approval for permanent birth control. Tubal sterilization is indicated when a woman does not want or cannot tolerate a pregnancy. This includes multiparous women not yet at menopause and women whose medical conditions are aggravated by or whose lives may be at risk during a pregnancy. The typical patient is a woman older than 30 years of age with two or more children and no plans for future childbearing. A patient should be screened carefully to determine if permanent sterilization is the correct form of birth control for her particular situation. For example, if she is concerned about protection against sexually transmitted disease and human immunodeficiency virus or regulating her menstrual cycle, permanent tubal sterilization may not be the best choice for her. The foremost contraindications to tubal sterilization are a desire to maintain childbearing potential and concerns about permanent sterility. Other contraindications include pregnancy or a recent or current pelvic infection given the possibility of infecting the implanted device. Specific contraindications for the Essure device include patients who have had prior tubal ligation, termination of a pregnancy or child delivery <6 weeks prior to placement, the limitation of one coil for placement in the patient (i.e., uterine anomaly with single fallopian tube or proximal tubal occlusion on the contralateral side), immunosuppression, and menorrhagia/menometrorrhagia without a diagnosis.36 Additional contraindications, which are annotated in the package insert for this device, are a known allergy to iodinated contrast media and a known hypersensitivity to nickel confirmed by a skin test. A contrast allergy can be addressed by premedicating the patient using prednisone and diphenhydramine. Nickel hypersensitivity with intravascular stents and orthopedic prostheses has been addressed in the literature.37–39 The possibility of early restenosis with nitinol intravascular stents in patients who exhibit nickel hypersensitivity has been debated.38,39 Although no work has been published concerning hypersensitivity with nitinol in the fallopian tubes, nickel allergy is likely to remain a relative contraindication given the unknown long-term effects that may result from this condition. The optimal setup for performing fluoroscopy-guided transcervical tubal sterilization includes an all-purpose fluoroscopy room with a rotating C-arm. The use of lithotomy stirrups is highly recommended. A kit for sterilely preparing the perineum and vagina is needed; draping the legs and abdomen is also necessary. Either a metal speculum that can be resterilized after use or a disposable plastic speculum can be used to access the vaginal vault and visualize the cervix. A transcervical catheter is needed for uterine cavity access; we use a 12F catheter with a 5F catheter inner diameter and a side arm (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN) for injecting contrast and saline. A sterile cervical tenaculum for traction and sterile set of disposable cervical dilators (Cook Medical) should be available for every case, but may not be needed necessarily. Long-handle sponge forceps are useful to keep the vaginal vault dry during and after the procedure. Iodinated contrast (Visipaque 320; Amersham Health, Princeton, NJ) is used to perform the initial hysterosalpingogram (HSG) with selective salpingograms, if necessary. A 40 cm angled-tip 4F catheter (Cook Medical) is preferred for the selective salpingograms. Because only the Essure device (Conceptus) is FDA-approved for transcervical BTS, all further references to the coil(s) will refer to this device (Fig. 13.1). The coil measures 4 cm in length with a maximum diameter of 2 mm when fully expanded (Fig. 13.2). An outer Nitinol coil surrounds a flexible stainless steel core wire containing polyethylene terephthalate fibers (Dacron; Invista Inc., Wichita, KS). The Dacron causes an inflammatory reaction in the fallopian tubes with resultant fibrosis limiting the possibility for tubal recanalization. The fibrotic in-growth occluding the tube at 3 months postprocedure has been well documented histologically.40 Fig. 13.1 The Essure device. The device contains the coil in its constrained configuration with a 10-degree angled tip to aid in selecting out the tubal ostium for placement. The outer diameter of the device shaft is 4.3F. Fig. 13.2 From top to bottom, fluoroscopic images of the Essure device and a deployed coil with a photograph of a deployed coil. The radiopaque markers are labeled 1 to 4. The third marker is ideally placed at the tubal ostium. The fallopian tube provides a conduit from the ovary to the uterus and consists primarily of circular and longitudinal smooth muscle fibers with multiple epithelial folds. The smooth muscle layers become thinner as the tube tracks from the uterus to the ovary; the diameter of the tube also increases correspondingly. The average fallopian tube measures 11 cm in length (range 7 to 16 cm) and is divided into four segments (Fig. 13.3): intramural (interstitial), isthmic, ampullary, and infundibular. The intramural segment is contained in the wall of the uterus beginning at the uterotubal ostium and ending at the uterotubal junction (UTJ). It measures 1.5 to 2.5 cm in length with a lumen of 0.8 to 1.4 mm in diameter in in vivo specimens.41 The narrowest point of the fallopian tube is at the UTJ. The isthmus begins at the UTJ and ends at the ampullary—isthmic junction. Its length ranges from 2 to 3 cm with a diameter of 1 to 2 mm, making it the narrowest extrauterine segment. The ampullary segment is the most variable; it ranges from 5 to 8 cm in length with a diameter of 1.5 mm at the ampullary—isthmic junction to 10 mm at the ampullary—infundibular junction. The infundibular segment contains the fimbria and the opening to the peritoneal cavity. The preprocedure workup prior to fallopian tube occlusion includes documentation of a recent pelvic examination with a normal Pap smear and negative gonorrhea and Chlamydia cultures. Fallopian tube embolization should be performed in the follicular phase (day 7 to 14) of the patient’s menstrual cycle to limit the chance of a luteal phase pregnancy. A qualitative urine human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) test is performed on the day of the procedure and the negative result documented before the start of the procedure. Preprocedure medications include 30 mg of ketorolac and 1 g of ceftriaxone intravenously. Ketorolac, a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID), is helpful for postprocedure pain and cramping and may help with tubal spasm. With radiologic procedures such as HSGs and fallopian tube recanalizations (FTR), periprocedural administration of antibiotics (i.e., doxycycline) is widely practiced, but not universally. At our institution, we administer antibiotics for all gynecologic interventions. No preoperative antibiotics were given during the Essure pivotal trial with 507 attempted hysteroscopic device placement procedures and there were no reported cases of infection.6 Fig. 13.3

Background

Patient Selection

Indications

Contraindications

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree