The undifferentiated gonads arise in utero prior to 7 weeks’ gestation from the interaction of primordial germ cells, sex cords (formed from mesenchymal tissue), and epithelium.

9 The Wolffian (mesonephric) structures and Mullerian structures are located lateral to the developing gonads. In girls, the gonads differentiate into ovaries between 7 and 8 weeks’ gestation by the complex interaction of several genes, including Wnt4,

23,

24 Foxl2,

23 CYP19,

24 RSPO1,

24 Pod1,

23 Dax1,

23,

25 and Fst,

23 and under the influence of multiple hormones, including B-catenin

24 and cytochrome P-450 aromatase.

25 Once ovarian differentiation begins, the primordial germ cells develop to form ˜2 million primordial follicles by the time of birth, eventually decreasing to around 400,000 by menarche. The sex cord cells become granulosa cells that surround the follicles in the outer, cortical portion of the ovary, whereas the central or medullary portion of the ovary is primarily connective and vascular tissues.

Ectopic, Supernumerary, and Accessory Ovary

The ovaries have been shown to have a higher incidence of maldescent in association with several Mullerian duct anomalies, specifically didelphys, unicornuate, and bicornuate uteri.

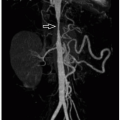

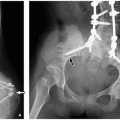

27 Maldescent is defined as the ovarian upper pole at or above the iliac vessel bifurcation (

Figs. 19.3 and

19.4). Ectopia of the ovary within the inguinal canal has been reported in a case of Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome.

28 Supernumerary ovaries are additional loci of ovarian tissue located above the pelvis, distinct from and unconnected to the orthotopic ovaries,

29 and they may be found in the omentum, retroperitoneum, or kidney. Supernumerary ovaries may be the result of disruption of the gonadal ridge tissue or abnormal gonadocyte migration prior to gonadal differentiation. Accessory ovaries are found within adnexal structures connected to the orthotopic ovary by shared blood supply and may be the result of splitting of the developing ovarian primordium.

29 Although rare, ectopic, supernumerary, and accessory ovaries are as equally prone to ovarian pathology as orthotopic ovaries.

29,

30 Supernumerary and accessory ovaries can be associated with other genitourinary tract anomalies.

Ovarian Dysgenesis

Ovarian dysgenesis encompasses disorders that result in an abnormal ovarian morphology and function, typically in the setting of DSD. 46XX testicular and ovotesticular dysgenesis are related to genetic mutations that alter gonadal cord development to include purely testicular or mixed ovarian and

testicular tissue in genotypic females.

19 46XY gonadal dysgenesis may also result in different degrees of ovotesticular dysgenesis with ambiguous internal and external organs. Turner syndrome (45XO) is characterized by streak ovaries due to loss of germ cells after 22 weeks’ gestation, despite initially normal ovarian development. Streak ovaries containing no germ cell components can also be found in 46XX ovarian dysgenesis.

31 45X/46XY mosaicism and 46XX/46XY chimerism result in ovotesticular dysgenesis because of mixed genetic signals during gonadal development.

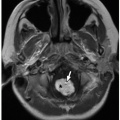

19Dysgenetic and streak gonads (

Fig. 19.5) are often not seen at imaging because of their small size and uncharacteristic appearance, having ill-defined margins and lacking the characteristic ellipsoid shape. Ovotesticular or testicular dysgenesis can have normally sized gonads that may be normal or ectopic in position and may be associated with abnormal Mullerian duct development and ambiguous genitalia.

9,

19 It is important to note that gonads appearing as morphologically ovarian or testicular tissue may be dysgenetic or can even represent abnormal fallopian tube or epididymis. Surgical biopsy with histologic evaluation is required for definitive gonad characterization.

9,

32Complications of dysgenetic and streak gonads include premature ovarian failure and primary amenorrhea; patients with a normal physical exam at birth may later present with delayed puberty because of hypoestrogenism.

31 In some cases, the abnormal germ cell derivatives may lack the genetic influence to mature completely, placing the patient at increased risk for malignancy.

8,

9,

19 Prophylactic removal of dysgenetic gonads is usually recommended in patients raised as girls because of the increased risk of neoplasia, including gonadoblastoma.

32

Ovarian Cyst and Follicle

A graafian or primordial follicle is tiny, measuring about 0.25 mm; this is the only type of follicle present in prepubertal children. In the neonatal ovary, subcentimeter follicles may be visible, but involute as the effects of maternal hormones subside.

1,

33,

34 Management of larger neonatal ovarian cysts is somewhat controversial. Lesions larger than 4 cm are prone to torsion

33,

34; however, some authors believe that many of these lesions arise in ovaries that have already infarcted from torsion in utero.

35 The differential diagnosis of these lesions includes mesenteric/omental cyst (lymphatic malformation) and enteric duplication cyst.

33 Ovarian neoplasms, including teratomas, are rare in neonates.

Torsed, infarcted ovaries may appear as abdominal or pelvic cysts or small calcified masses at birth.

2 Imaging evaluation of neonatal ovarian cysts is usually carried out using ultrasound (

Fig. 19.6). Some authors advocate intervention to prevent the complications of torsion, hemorrhage, or bowel obstruction with either ultrasound-guided aspiration for optimal ovarian salvage

34 or cystectomy, particularly in cases of suspected acute torsion. Follow-up ultrasound to document cyst involution is an alternative approach for smaller lesions.

35In the older child, as follicles mature, their walls thicken and their centers fill with fluid. The mature or dominant follicle can reach a size of up to 3 cm before rupturing and discharging the ovum.

36 After ovum release, follicular lining cells

luteinize, then regress as vascular tissue grows into the folds of the collapsed follicular walls, eventually involuting to form the corpus albicans.

At ultrasound, a corpus luteum can vary in appearance from an irregular, thick-walled cyst to a more solid appearing, collapsed lesion with low-resistance spectral Doppler waveforms in their wall.

36 At contrast-enhanced CT and MRI, the walls of these cysts usually appear thickened and hyperenhancing with crenated margins. The ovulating ovary and corpora lutea also show increased uptake on

18F-FDG-PET (

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography), simulating pelvic lymphadenopathy or ovarian neoplasm.

37Failed ovulation can result in a functional cyst that usually remains simple, but may grow causing pain.

36 In postpubertal girls, simple ovarian cysts up to 3 cm most likely represent a dominant follicle (with rupture either impending or failing to occur) or persistence of the corpus luteum as a cyst after ovulation.

1,

36 Although uncommon, autonomously functioning follicular cysts (

Fig. 19.7) are a common cause of peripheral precocious puberty.

14 A cyst larger than 9 mm in a girl with precocious puberty should raise a question of an autonomously functioning follicular cyst or hormone-producing tumor

14 requiring resection. Observation is generally sufficient for nonfunctioning cysts; however, aspiration may be needed for large ovarian cysts to minimize the risk of future ovarian torsion.

14Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts are generally from corpora lutea, which typically have bloody contents (

Fig. 19.8); they vary in appearance depending upon the age of the hemorrhage.

1,

36,

38 At ultrasound, they may appear echogenic without posterior acoustic shadowing; may contain dependent debris, fluid-debris levels, or retracted, avascular, lobulated blood clot (

Figs. 19.9 and

19.10); or may contain lacy or cobweb-appearing fibrinous strands. Retracted blood clot within a cyst does not have blood flow on color Doppler ultrasound and may move with ballottement with the transducer (this is evaluated by applying gentle pressure with the transducer followed by release to assess movement within the fluid), whereas a solid tumor nodule does not. The cyst contents should not have

blood flow on Doppler ultrasound evaluation and should not enhance on CT or MRI. At contrast-enhanced CT, a hemorrhagic cyst may appear hyperdense compared to other follicles, but is still less attenuating than surrounding enhanced ovarian stroma. A hematocrit effect may be observed. The MRI appearance depends upon the age of the hemorrhage. Signal hyperintensity on both non-fat-saturated and fat-saturated T1-weighted MR images is a reliable indicator of the presence of hemorrhage. These lesions may show lower than expected signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images, often referred to as “T2 shading,” which is the result of evolving blood products (

Fig. 19.10). Other causes of blood-filled ovarian cysts besides corpora lutea include posttorsion/infarct and endometriotic cyst, both rare in childhood.

Functional hemorrhagic cysts typically resolve or at least decrease in size over 1 to 2 menstrual cycles.

1 If there is acute and sometimes painful cyst rupture, the cyst may appear collapsed or may be no longer visible with a variable amount of free pelvic fluid that may contain low-level echoes due to hemorrhage. Management is usually conservative. For simple cysts in postmenarchal girls measuring 3 to 5 cm, follow-up is commonly not required.

36 Follow-up ultrasound is recommended for simple cysts measuring >5 cm and less than or

equal to 7 cm,

36 although aspiration may be warranted to prevent potential torsion. Intervention may also be required for larger cysts for pain control or in case of suspected ovarian torsion, with laparoscopic cyst aspiration or cystectomy most often performed. Simple cysts larger than 7 cm require further evaluation with MR imaging or laparoscopy.

36

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) consists of hyperandrogenism, enlarged polycystic ovaries, and obesity. Affected patients often present with menstrual cycle irregularity and may have insulin resistance.

39 The incidence of PCOS in adolescents is about 3%,

40 although 16% of girls presenting with menstrual irregularity were diagnosed with PCOS in one study.

41 There is likely a genetic basis for the disease, which has been proposed to represent a form of arrested adrenarche.

40 Given the association of this syndrome with insulin resistance and hypertension, implications for long-term cardiovascular health make PCOS important to detect.

Diagnostic criteria include physical examination evidence of hyperandrogenism; hormonal imbalances, including testosterone elevation and an elevated LH/FSH ratio; oligo- or amenorrhea; insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia; and polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM).

40 Accelerated bone maturation may also be present.

42 Because ovaries containing multiple follicles of up to 1 cm can be normal during adolescence,

43 a diagnosis of PCOS should be only be considered if the abnormal ovarian morphology is accompanied by other clinical or laboratory evidence of PCOS.

20,

39,

40 Normal ovarian morphology does not exclude the diagnosis of PCOS.

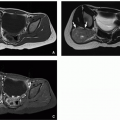

The criteria for PCOM include an ovarian volume of more than 10 mL with or without 12 or more follicles in each ovary measuring 2 to 9 mm in diameter

44 (

Fig. 19.11). Follicular distribution and stromal hyperechogenicity are not included

in these criteria. Although both ovaries are typically affected, findings may be seen in only one ovary.

Transvaginal ultrasound is the ideal imaging modality for evaluation of ovaries and ovarian follicles in adolescent pediatric patients with clinically suspected PCOS; however, transvaginal ultrasound may not be appropriate in girls who are not sexually active. When evaluating PCOM with ultrasound, ovarian volumes should be calculated utilizing the simplified formula for a prolate ellipsoid (0.52 × length × width × height).

44 If a dominant follicle (>10 mm) or a corpus luteum is encountered, repeat ultrasound is recommended during the next menstrual cycle. Some authors

36,

45 have suggested a threshold of at least 19 or more follicles as criteria for diagnosing PCOS; however, these studies were performed using transvaginal probes.

Current treatments for PCOS include weight reduction, hair growth suppression and/or removal, insulin-sensitizing agents (e.g., metformin), and hormonal therapy with oral contraceptives or antiandrogens.

39,

40