External and Internal Genitalia

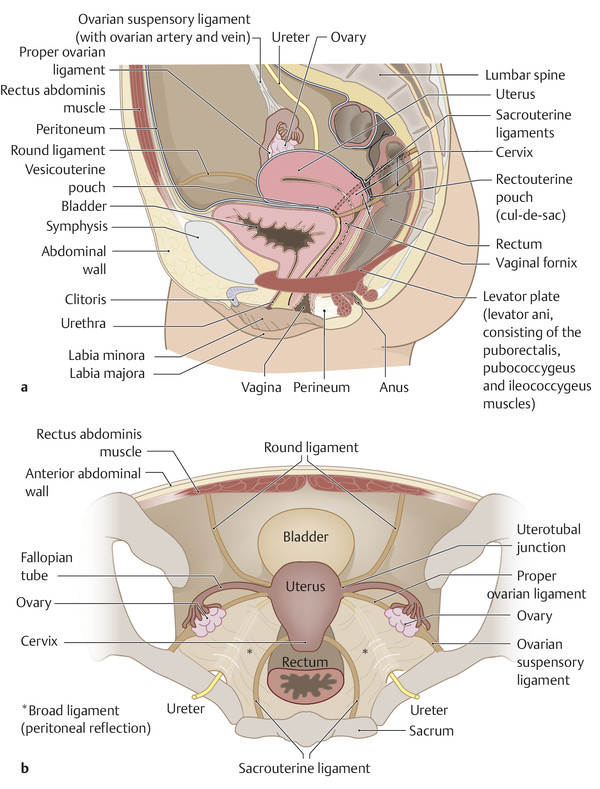

The female external genitalia (vulva) extend from the mons pubis across the introitus (opening of the urethra and vagina) to the perineum. The internal genitalia consist of the uterine corpus, cervix, vagina, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. The pelvic organs are invested by peritoneum. Anterior to the uterus, the peritoneal cavity extends between the uterine isthmus and posterior bladder wall to form the vesicouterine pouch. The rectouterine pouch, called also the cul-de-sac or pouch of Douglas, is the extension of the peritoneal cavity between the rectum and the cervix and posterior uterine wall (▶ Fig. 12.1).

Fig. 12.1 Lateral and axial views of the female pelvis. (a) Diagram illustrating the position of the pelvic organs, the peritoneal pouches, the major suspensory ligaments, and the pelvic floor muscles for orientation and reporting. (b) Cross section through the female pelvis to display the relationships of the organs and suspensory ligaments.

Because the female internal genitalia are stabilized within the pelvis by suspensory ligaments, the uterus is subject to a number of positional variants that are influenced by the degree of bladder and rectal distention. In approximately 90% of cases the uterus occupies an anteflexed and anteverted position. The size of the uterus is also variable and depends upon age, hormonal status, pregnancy, and any prior radiation exposure.

The main parts of the uterus are the corpus (body), fundus, isthmus, and cervix (▶ Fig. 12.2). The uterine corpus is composed of three layers:

Endometrium: the inner mucosal layer, whose thickness depends on age and hormonal status.

Myometrium: the middle muscular layer, separated from the endometrium by a very thin junctional zone (the inner myometrium).

Perimetrium: a thin peritoneal layer.

Fig. 12.2 Anterior view of the female pelvic organs. Diagrammatic representation of the arterial blood supply and venous drainage of the pelvic organs.

The vagina is located between the urethra, the bladder, and the rectum. Its superior portions are the anterior and posterior fornices. It terminates distally at the vaginal orifice. The approximately 10-cm-long muscular tube of the vagina is surrounded by connective tissue—the paracolpium.

The fallopian tubes (uterine tube, salpinx) are each approximately 10 to 14 cm long and 1 to 4 mm in diameter. Each of the paired fallopian tubes arises from a superiorly tapered extension of the uterine cavity called the intramural or interstitial part of the tube. The narrow proximal tubal segment, called the isthmus, widens laterally to form the ampulla before terminating at the fimbriated end close to the ovary. An open communication exists between the fallopian tube and the abdominal cavity. The tube runs at almost a 90° angle at its junction with the uterine corpus; this area is called the uterotubal junction or uterine horn. Each of the fallopian tubes lies lateral to the uterus and is attached to the uterine broad ligament via the mesosalpinx (see ▶ Fig. 12.2). 1, 2

The ovaries are paired gonads located within the ovarian fossa on the lateral wall of the lesser pelvis (within the bifurcation of the common iliac artery). Structures in close relation to the ovary are the obturator nerve, ureter, external iliac vein, internal iliac artery and vein, umbilical artery, and obturator artery. Each ovary measures approximately 4 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm, has an ovoid shape, and is attached to the back of the uterine broad ligament by the mesovarium. The ovary is attached to the uterus at the level of the uterine horns by the proper ovarian ligament, and it is bound to the pelvic sidewall by the ovarian suspensory ligament (infundibulopelvic ligament; see ▶ Fig. 12.2). 1, 2, 3

The ovarian stroma consists of two zones 1:

Cortex: The ovarian cortex contains follicles at various stages of maturity and also the corpora lutea.

Medulla: The ovarian medulla is composed of connective tissue, smooth muscle cells, and elastic fibers and is traversed by blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves.

The zonal anatomy of the ovary is less clearly defined in postmenopausal women than in women of reproductive age. The postmenopausal ovaries are frequently atrophic, and the stroma undergoes increasing fibrous transformation.

The fallopian tube and ovary are often referred to collectively as the adnexa.

12.1.2 Suspensory Apparatus

The pelvic organs are held in place by a suspensory apparatus consisting of various ligaments, connective tissue, and smooth muscle cells (see ▶ Fig. 12.1).

Broad ligament: The broad ligament is a transverse reflection of peritoneum that attaches the uterus to the pelvic sidewall and envelops the fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Round ligament: This superiorly placed ligament originates at the uterine horns, curves along the pelvic sidewall, then passes through the inguinal canal and inserts into the labia majora.

Cardinal ligament (transverse cervical ligament): The cardinal ligament is located at the base of the broad ligament. It is considered part of the parametria and is traversed by the ureter and blood vessels on each side.

Parametria: The parametria are suspensory structures that include the pubocervical fascia (pubocervical ligament, pubovesical ligament), which runs anteriorly along the bladder to the pubis, and the sacrouterine (rectouterine) ligament, which runs posteriorly along the rectum to the sacrum.

12.1.3 Pelvic Floor

The lesser pelvis is bounded inferiorly by the pelvic floor, which stretches between the symphysis, the pubic rami, and the ischial tuberosities. It consists of a total of three layers, which are formed by several muscles that blend together and function chiefly to suspend the pelvic organs and prevent descent of the pelvic floor 2:

Superior layer (posterior portion of the pelvic floor): This layer forms the pelvic diaphragm and contains the coccygeus muscle and the levator ani comprising portions of the ileococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis muscles.

Urogenital diaphragm (anterior portion of the pelvic floor): This is a fibrous layer composed of tough connective tissue stretching between the pubic rami and the ischia and containing the deep transverse perineal muscle (m. transversus perinei profundus) and, at its inferior border, the superficial transverse perineal muscle (m. transversus perinei superficialis).

Inferior layer (sphincter plane): This layer consists of the external pelvic floor muscles and perineal muscles and contains the external anal sphincter, bulbospongiosus, and ischiocavernosus muscles (see ▶ Fig. 12.1).

12.1.4 Blood Supply

The female pelvic organs receive most of their arterial blood supply from the paired ovarian arteries, each of which arises directly from the infrarenal abdominal aorta and runs retroperitoneally down the psoas muscle and along the ovarian suspensory ligament to the ovary (supplying the ovary and fallopian tube). The ovarian artery runs over the uterine artery, which arises from the internal iliac artery on the corresponding side, and passes distally into the uterine broad ligament, crossing anterior to the ureter. At the cervical level it divides into two tortuous branches, an ascending branch (supplying the ovary, fallopian tube, and uterus) and a descending branch (supplying the vagina and cervical ring).

Blood is collected by venous plexuses on the cervix, vagina, uterus, and ovary, from which it drains chiefly through the internal iliac veins. The ovarian vein opens directly into the inferior vena cava on the right side; on the left side it opens into the left renal vein (see ▶ Fig. 12.2). 2

12.1.5 Lymphatic Drainage

Because the lymphatic vessels in the pelvis form an arborizing system composed of multiple trunks, vessels, and anastomoses, the lymphatic return from the female pelvic organs drains to various groups of lymph nodes, some of which are not directly adjacent to the organ 3:

Lymph from the ovary and distal fallopian tube drains primarily to upper para-aortic lymph nodes and to pelvic or inguinal lymph nodes. 4

Lymph from the uterine corpus and proximal fallopian tube can drain primarily to locoregional parametrial lymph nodes, iliac and sacral lymph node groups, directly to para-aortic lymph nodes at the level of the renal vein, or to inguinal lymph nodes.

Lymph from the cervix drains primarily to parametrial, sacral, and iliac nodal groups.

Lymph from the upper two-thirds of the vagina drains primarily to iliac lymph nodes above the inguinal ligament, while the lower one-third of the vagina and the vulva are drained primarily by inguinal and femoral lymph nodes. 3, 5

Caution

An understanding of the various lymph node groups is relevant in patients with pelvic malignancies to avoid missing lymph node metastases that could potentially alter the treatment strategy.

12.2 Imaging

If the pelvic examination and ultrasound scans yield equivocal findings, more detailed imaging studies should be performed for the exclusion of malignancy or the staging of confirmed disease.

The sectional imaging modality of choice is MRI because of its excellent soft-tissue contrast, high level of detail, and variable sequence options, which can supply a diagnosis even without IV administration of contrast medium (▶ Fig. 12.3).

Fig. 12.3 Axial MR image of the female pelvis. Unenhanced T2W sequence to display anatomical relationships. 1, femoral vein; 2, symphysis; 3, bladder; 4, femoral artery; 5, round ligament; 6, diverticulum; 7, ilium; 8, sacrum; 9, iliac vessels; 10, sigmoid colon; 11, uterine corpus; 12, proper ovarian ligament; 13, acetabulum; 14, ovary; 15, follicle.

CT is definitely inferior to MRI for imaging the pelvic organs because of its relatively poor soft tissue contrast. Its main role is in planning radiotherapy, the detection of distant metastases, or the acute investigation of unexplained pelvic pain. If abdominal images are available from a CT examination for a nongynecologic indication, venous-phase images of the pelvic organs may provide useful information (▶ Fig. 12.4).

Fig. 12.4 Axial CT scan of the female pelvis. Venous-phase scan to display anatomical relationships. 1, small-bowel loops; 2, bladder; 3, rectus abdominis; 4, uterine cavity; 5 uterine corpus; 6, bowel; 7, sacrum; 8, small bowel; 9, roof of acetabulum; 10, ovary; 11, fallopian tube; 12, femoral vein; 13, femoral artery.

PET is most rewarding in the detection of recurrence or occult metastasis. 6, 7

Note

Image interpretation and reporting should always follow a structured routine to ensure that all questions of gynecologic interest are addressed. Especially in the evaluation of a primary tumor, all criteria that may influence tumor staging should be taken into account and noted in the report.

12.2.1 Transabdominal Ultrasound

Transabdominal ultrasound scanning provides an overview of the internal genitalia using the distended bladder as an acoustic window. Bladder distention also displaces loops of small bowel out of the lesser pelvis, which is essential for evaluating the ovaries.

An abdominal transducer is acceptable in most patients. In girls, young women, or very thin patients, a linear-array transducer with a tissue harmonic imaging option can provide better spatial resolution of the pelvic organs, with some reduction in scanning depth.

12.2.2 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Patients are imaged in the supine position with a high-resolution surface coil. Patient preparations should include the following:

Moderate bladder distention: A moderately distended bladder permits a more accurate evaluation of the bladder wall and posterior fat plane. The distended bladder also moves to a more upright position in the lesser pelvis, which simplifies anatomical orientation for angled sequences.

Administration of butylscopolamine to immobilize the bowel: An antiperistaltic agent is given to minimize motion artifacts. Contraindications are raised intraocular pressure and cardiac arrhythmias, in which case glucagon is an acceptable substitute (contraindicated in patients with diabetes mellitus).

Vaginal distention: When in a physiologically collapsed state, the vagina is distended with 20 to 40 mL of (sterile) ultrasound gel to improve the visualization of vaginal structures and the cervix. Intravaginal gel is also helpful in hysterectomized patients, as it can improve the detection of vaginal stump recurrence.

Unenhanced high-resolution T2W TSE sequences are essential for morphological evaluation of the female pelvic organs. The pelvic protocol should always include a contrast-enhanced fat-saturated T1W sequence, which will add significant information in almost any investigation. 8, 9, 10, 11 Where available, the use of a DWI sequence with b values of 800 to 1000 is also recommended for staging the primary tumor and lymph nodes. 12, 13, 14 A fat-saturated T2W sequence is helpful for evaluating inflammatory changes or fistulas, especially in cases where IV contrast medium cannot be used. An axial unenhanced T1W sequence or proton-density sequence is used for lymph node detection. An unenhanced fat-saturated T1W sequence is recommended for the differentiation of fatty or hemorrhagic components (particularly relevant for an ovarian mass). 15

Note

Evaluation of the female pelvic organs requires organ-specific angulation of the MRI sequences. The image orientation may have to be adjusted during the examination (as bladder distention increases).

Sagittal sequences should be prescribed in axial paramedian slices to obtain longitudinal sections of the uterine corpus and cervix in one plane. The axial oblique slices should always be individually adjusted for organ position and indication and may not correspond to the axial or coronal planes of the body axis. 8

The longitudinal axis through the lumen of interest serves as the reference standard for organ-specific angulation of the MRI sequences. The prescribed images are angled perpendicular to the reference organ (for axial, short-axis views) or parallel to it (for coronal views). In this way the reference organ should present a ring or “doughnut” appearance in the axial sections (▶ Table 12.1, ▶ Fig. 12.5). For anatomical orientation, the angled oblique scans can be preceded by a fast T2W sequence in axial and coronal planes relative to the cardinal body axis.

Organ, indication | Structures that define the longitudinal reference axis for image orientation |

Endometrium, uterine corpus | Corpus lumen |

Cervix | Cervical canal |

Vagina, tumor recurrence after hysterectomy | Vaginal canal, vaginal stump |

Vulva | Distal urethra at the level of the introitus |

Ovary | Parallel to the corpus lumen, especially for localizing masses to the ovary or uterus |

Fig. 12.5 MRI planes angled relative to specific pelvic organs. Thick lines denote the longitudinal axis for prescribing perpendicular axial slices (thin lines) and parallel coronal slices.

12.2.3 Computed Tomography

Multidetector CT can quickly scan the body region of interest in axial sections with submillimeter resolution, and the acquired data can be processed into multiplanar reformatted images with essentially the same resolution. 16 The examination should be performed with IV administration of contrast medium. Nevertheless, even in the recommended venous phase of enhancement, soft-tissue contrast is still inferior to that of unenhanced MRI.

12.2.4 Differential Diagnosis

A knowledge of differential diagnoses is helpful in selecting the proper imaging modality, allowing for protocol modifications and thereby simplifying the diagnostic procedure. Good history taking is essential. In women who present with lower abdominal pain, it is important to describe the pain characteristics, the onset and duration of the pain, its location, and any previous operations or diseases. Some important considerations in the differential diagnosis of acute or chronic lower abdominal pain are listed below:

Acute lower abdominal pain: 17, 18

Ruptured ovarian cyst.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst.

Pelvic inflammatory disease.

Tubo-ovarian abscess.

Adnexal torsion.

Acute necrosis of a pedunculated leiomyoma due to torsion.

Ectopic pregnancy.

Appendicitis.

Diverticulitis.

Urinary tract infection.

Ureteral colic.

Chronic lower abdominal pain: 19

Endometriosis.

Uterine adenomyosis.

Leiomyomas.

Polyps.

Chronic inflammation.

Adhesions.

Pelvic varicosity.

Retroverted uterus.

Anomalies.

Adnexal mass.

Neoplasm.

Ascites due to malignancy.

12.3 Congenital Anomalies

Congenital anomalies of the female genitalia may be caused by genetic defects or exposure to exogenous agents. They result from a failure or deficiency of formation such as deficient growth, failure of canalization, or incomplete fusion of the müllerian ducts. 20 The anomalies are often detected in routine pediatric examinations, whereupon the diagnosis is usually confirmed by transabdominal ultrasound or fluoroscopic examination after retrograde administration of contrast medium. If necessary, MRI may be helpful for the more detailed characterization of complex anomalies.

Note

Given the close proximity of the internal genitalia and urinary tract, genital malformations are commonly associated with urinary tract anomalies, which should also be investigated. 20

12.3.1 Bicornuate Uterus, Uterus Didelphys, and (Sub)Septate Uterus

Brief definition Abnormalities of differentiation that occur between weeks 9 and 12 of gestation lead to various duplication anomalies of the uterus and vagina. The following disorders are distinguished 20:

Anomalies that involve absent or incomplete fusion of the müllerian ducts—especially a bicornuate unicollis or bicollis uterus (uterus bicornis unicollis or bicollis) and uterus didelphys

Anomalies that involve absent or incomplete reabsorption of the septum after normal fusion of the müllerian ducts—especially a (sub)septate uterus and arcuate uterus

Imaging signs (▶ Fig. 12.6)

Failure of fusion:

A bicornuate unicollis uterus has two uterine cavities that open into one cervix. The central myometrium extends to the internal os.

A bicornuate bicollis uterus has two uterine cavities and two cervices (▶ Fig. 12.7). The central myometrium extends to the external os.

Uterus didelphys involves a complete duplication of the uterus with one horn each, two separate cervices, and a possible double vagina (double uterus with a double vagina or vaginal septum).

Absent or incomplete septal reabsorption:

In a septate uterus, the septum extends to the cervix.

In a subseptate uterus, the septum is present only within the uterine cavity.

In an arcuate uterus, the fundus bulges into the uterine cavity.

Fig. 12.6 Uterine anomalies. (a–c) Anomalies due to incomplete fusion of the müllerian ducts. (d–f) Anomalies due to absent or incomplete septal reabsorption.

Fig. 12.7 Bicornuate bicollis uterus. Fat-saturated axial T2W image reveals two uterine horns and two cervices. The central myometrium extends to the external os, creating the characteristic pattern of a bicornuate bicollis uterus. A small corpus cyst and two small cervical cysts (nabothian follicles) are incidental findings without pathologic significance.

Clinical features Most women are asymptomatic, but the anomalies are frequently associated with reproductive failure and pregnancy loss.

12.3.2 Hymenal Atresia

Brief definition If perforation of the hymen—which separates the vagina from the urogenital sinus during development—fails to occur, the hymenal epithelium is transformed into fibrous connective tissue that obstructs outflow from the uterus. Hymenal atresia is the most common congenital anomaly with otherwise normal formation of the internal genitalia. The reported incidence ranges from 1:1,000 to 1:16,000. 5, 21, 22

Imaging signs The vagina is distended by mucus, blood, and blood breakdown products. The diagnosis of hymenal atresia can be confirmed by transabdominal ultrasound (limited penetration depth) or high-resolution MRI without contrast medium (for surveying the whole lesser pelvis).

Clinical features Young girls may complain of monthly colicky pains or may present with an acute abdomen. Complaints first appear after menarche and result from the accumulation of blood first in the vagina (hematocolpos), then in the uterus (hematometra), and finally in the fallopian tube (hematosalpinx) due to the obstructive effect of the imperforate hymen. There may be associated dysuria, urinary retention, and constipation. Girls are asymptomatic as infants, as only mucus is retained in the vagina (mucocolpos). 20

12.3.3 Uterovaginal Agenesis

Brief definition The incidence of this autosomal disorder, also known as Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser syndrome, is approximately 1:5,000 female births. The syndrome is characterized by a rudimentary uterus and fallopian tubes with vaginal aplasia. But because the ovaries develop normally and have normal function, the external genitalia are female. This condition is often associated with renal anomalies, usually in the form of a horseshoe kidney, as well as skeletal malformations (e.g., fused cervical vertebrae or rudimentary vertebral bodies). 20

Clinical features Girls with uterovaginal agenesis become symptomatic at puberty, presenting with primary amenorrhea.

Imaging signs The rudimentary development of the uterus and vagina is detectable with transabdominal ultrasound. If necessary, unenhanced high-resolution MRI of the pelvis is helpful in confirming the diagnosis, as it provides a survey view of the lesser pelvis and demonstrates normal development of both ovaries.

12.4 Diseases

12.4.1 Inflammatory Changes

Brief definition Pelvic inflammatory disease in women may be caused by a primary infection of the uterus, fallopian tube, or ovaries with microorganisms (especially chlamydia, mycobacteria, gram-negative bacteria, or gonococci) leading to salpingitis, endometritis, pyosalpinx, or even a tubo-ovarian abscess. Bacterial colonization during or after menstruation, in the postpartum period, or after gynecologic or other surgical procedures may provoke an acute inflammatory process; or inflammation may spread from an adjacent organ to the internal genitalia, usually secondary to appendicitis or diverticulitis. Infection may spread from the fallopian tubes to the peritoneal cavity or may disseminate by the lymphogenous or hematogenous route, as in ▶ tuberculosis, for example. If an inflammation becomes chronic (due to a silent course or recurrent inflammations), it may lead to tubal or other adhesions with secondary complications such as infertility or ectopic pregnancy. 11

Imaging signs The initial imaging study of choice is ultrasound.

Caution

Imaging signs on CT and MRI:

Endometritis: The endometrium is thickened and the uterine cavity is filled with fluid. Concomitant myometritis is often present and is manifested by edematous thickening of the myometrium.

Hydrosalpinx, hematosalpinx, and pyosalpinx: Hydrosalpinx, caused by tubal obstruction due to postinflammatory adhesions, endometriosis, or even a malignant process, is characterized by fluid retention with dilatation of the tubal lumen, which may be several centimeters in diameter or may assume a C– or S-shaped configuration (▶ Fig. 12.8). With hematosalpinx, the dilated tubal lumen is hyperechoic on ultrasound and shows increased attenuation on CT and increased T1W signal intensity on unenhanced MRI. Superinfection leads to pyosalpinx, appearing as a distended tube with hypervascular wall thickening. The intraluminal fluid may be heterogeneous, depending on its protein content. An air–fluid level is pathognomonic but not always detectable. 23

Fig. 12.8 Hydrosalpinx. Venous CT reveals a C-shaped, fluid-filled structure with prominent walls and contrast enhancement posterior to the homogeneously enhancing uterus, consistent with a distended fallopian tube (hydrosalpinx).

Salpingitis and oophoritis: In salpingitis, the fallopian tube is edematous and the wall shows intense enhancement. Frequently the lumen is not dilated. The surrounding tissue shows inflammatory imbibition. In oophoritis the ovary is enlarged and shows loss of corticomedullary differentiation. There is usually surrounding free fluid. 11, 23

Tubo-ovarian complex (adnexitis) and tubo-ovarian abscess:

Tubo-ovarian complex typically presents as a fluid-filled multicystic mass. The fallopian tube and ovary can still be differentiated.

A tubo-ovarian abscess, on the other hand, appears as a thick-walled mass that is poorly delineated from the uterus and small-bowel loops and may include both cystic and solid components, internal septa, and possible gas collections. It enhances intensely due to the inflammatory component. 24, 25 Imbibition is often seen in the fatty tissue around the primary inflammatory process. Possible associated findings are adhesions, thickening of the uterosacral ligaments, reactive lymphadenopathy, and free fluid in the lesser pelvis. 11, 26, 27

Note

Tubo-ovarian abscess may closely resemble ovarian carcinoma in its imaging appearance. However, primary ovarian carcinoma is not associated with a dilated fallopian tube and usually lacks a perifocal inflammatory reaction. Differentiation is aided by imaging an additional plane that shows continuity of the abscess with a dilated fallopian tube. 25, 28

Clinical features Women with acute pelvic inflammatory disease often present with lower abdominal pain, fever, and positive serum markers for infection. In approximately 20% of cases, however, the patient may be afebrile with a white blood count that is within normal limits. 11 The rupture of a tubo-ovarian abscess may incite a life-threatening peritonitis. 25 The secondary involvement of surrounding structures may cause bowel obstruction or an intraperitoneal abscess. Chronic inflammation often leads to nonspecific lower abdominal complaints and may cause back pain due to adhesions.

Differential diagnosis 29

Appendicitis.

Diverticulitis.

Urinary tract infection.

Ectopic pregnancy.

Endometriosis.

Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst.

Uterine leiomyomas.

Ovarian cancer.

Fallopian tube cancer

Hydrosalpinx in particular requires differentiation from the following:

Cystic ovarian tumor.

Ileus (but ultrasound shows peristalsis).

Pelvic varicosities (ultrasound shows intraluminal echoes and Doppler blood flow; the veins enhance on postcontrast CT and MRI).

Epithelial stromal tumor of the ovary.

Key points The MRI protocol for female pelvic inflammatory disease should include the following sequences:

High-resolution, thin-slice (3–4 mm) T2W TSE sequence in at least two planes.

Unenhanced axial T1W sequence.

Fat-saturated axial T2W sequence.

Contrast-enhanced and fat-saturated T1W sequence in two planes.

Tuberculosis of the Genital Tract

The fallopian tubes are the most common primary site of involvement by tuberculosis in the female pelvis, and the involvement is usually bilateral. Spread to adjacent genital organs may occur by the hematogenous or the lymphogenous route. On the whole, only 1.3% of women with tuberculosis develop genital tract involvement. 23, 27

Imaging signs

Tubercular salpingitis: The fallopian tubes are dilated, with no evidence of obstruction, and their walls are thickened. The tubes may show an S-shaped or string-of-beads configuration and enhance intensely after IV administration of contrast medium.

Tubercular tubo-ovarian abscess: This lesion appears as a solid or mixed cystic–solid ovarian mass, possibly with small nodules and septa within the cystic portion. Calcifications are sometimes seen. Other findings are free fluid, thickening of the peritoneum with peritoneal nodules, and areas of mesenteric and omental soft-tissue infiltration. 27 On MRI the abscess has heterogeneous signal intensity in T2W sequences (hypointense solid component, hyperintense cystic component, hypointense nodules). The abscess is hypointense to moderately hyperintense in T1W sequences, depending on its protein content. The solid components, septa, and peritoneum show intense enhancement. Ascites, which shows very high T2W signal intensity, is permeated by thin septa of low T2W signal intensity. 27

Clinical features Patients complain of acute or chronic lower abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Peritonism is detected in approximately one-half of patients. Infertility or an elevated CA 125 level may also be found. In most cases, however, genital tuberculosis is detected incidentally in curettage material or during laparoscopic biopsy. 30

Differential diagnosis

Ovarian carcinoma.

Peritoneal metastases.

Vaginal Fistulas

Brief definition Vaginal fistulas may occur as a result of surgery (especially hysterectomy), inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or radiotherapy, or in the setting of a congenital anomaly.

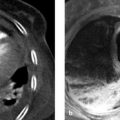

Imaging signs Because fistulas may be quite extensive and may even form a complex, branched network of burrowing tracts, MRI is the modality of choice for obtaining an overall view. The rectal or vaginal introduction of fluid or ultrasound gel facilitates detection, especially of small-caliber tracts. The fistulous tract is very hyperintense in the fat-saturated T2W sequence. The surrounding tissue may show an inflammatory reaction, depending on activity, and will then show increased signal intensity. Fluid collections or abscesses may also be found (▶ Fig. 12.9).

Fig. 12.9 Vaginal fistula. High-resolution coronal T2W image. The fluid-filled bladder is seen cranial to the vaginal stump, which is distended with ultrasound gel. The fluid-filled bean-shaped structure on the right side is a collection resulting from a posthysterectomy vesicovaginal fistula (arrow). The surrounding soft tissue does not show an associated inflammatory reaction.

Clinical features The clinical presentation depends on inflammatory activity, location, and the structures that communicate with the vagina through the fistulous tract. Vesicovaginal, rectovaginal, enterovaginal, and colovaginal fistulas are commonly found.

Key points A thin-slice (fat-saturated) T1W sequence in two planes is recommended for the detection of vaginal fistulas. The axial plane is angled relative to the vagina, and a sagittal or coronal sequence may have to be added for complete visualization. Fistula imaging is also aided by a thin-slice, contrast-enhanced T1W sequence with fat saturation.

12.4.2 Benign Lesions and Pseudotumors

Cysts of the Uterus, Vulva, and Vagina

Brief definition Cysts may arise in the endometrium or cervix (nabothian follicles) and from the Bartholin’s glands (Bartholin’s cysts) or vaginal Gartner’s ducts (Gartner’s duct cysts). They are incidental imaging findings.

Imaging signs When imaged sonographically, simple cysts have smooth margins and are devoid of internal echoes. On MRI they are hypointense in unenhanced T1W sequences and very hyperintense in T2W sequences (see ▶ Fig. 12.7 and ▶ Fig. 12.10c). Proteinaceous contents or intracystic hemorrhage produce high-amplitude internal echoes at ultrasound, increased signal intensity on T1W images, and heterogeneous signal intensity on T2W images. The cysts have smooth margins on CT scans, and attenuation values in the cysts depend on protein content (see ▶ Fig. 12.7, ▶ Fig. 12.10c, ▶ Fig. 12.16, and ▶ Fig. 12.23a).

Fig. 12.10 Benign cystic lesions of the ovary. MRI appearance. (a) High-resolution sagittal T2W image. The thick-walled cystic lesion with a slightly irregular appearance in the lower part of the ovary is a corpus luteum cyst (arrow). Several follicles at various stages of maturity are also visible in the cortex. (b) High-resolution axial T2W image shows multiple simple cysts in the left ovary anterior to the psoas muscle. (c) High-resolution sagittal T2W image. A large, simple ovarian cyst abuts the uterine fundus. Several simple nabothian follicles are visible within the cervix.

Fig. 12.11 Endometriotic cyst and uterine adenomyosis. High-resolution axial T2W image shows a cystic lesion with a fluid level in the right ovary due to varying proportions of blood breakdown products (confirmed as an endometriotic cyst). The uterine corpus shows diffuse wall thickening and small hyperintense spots caused by the implantation of endometrial cells in uterine adenomyosis. Simple cysts are visible in the cervix.

Fig. 12.12 Stage pT1b pN0 endometrial carcinoma. (a) High-resolution sagittal T2W image shows a moderately hyperintense tumor growing from the endometrium into the myometrium of the anterior uterine wall and showing greater than 50% myometrial invasion (arrow). Tumor does not extend to the serosa. (b) Axial fat-saturated T1W image after administration of contrast medium. The hypointense tumor is demarcated relative to the myometrium. The image confirms absence of serosal involvement.

Clinical features Cysts of the uterus, vulva, and vagina usually do not produce clinical symptoms.

Differential diagnosis Bartholin’s cysts may become superinfected (bartholinitis) and may undergo secondary abscess formation or even malignant transformation resulting in ▶ Bartholin’s gland carcinoma.

Brief definition Most simple cystic lesions of the ovary are functional cysts (developing from an unruptured graafian follicle) smaller than 3 cm in diameter. Lesions must measure more than 3 to 4 cm to qualify as “ovarian cysts.” They may have thin internal septa and may show intracystic hemorrhage. Corpus luteum cysts develop from the remnants of a ruptured graafian follicle. They may reach several centimeters in size and often show a thickened, irregular wall. 15, 31, 32 The terms “polycystic ovary syndrome” or “Stein–Leventhal syndrome” refer to a disease in which a hormonal disorder leads to a firm, thickened ovarian capsule on both sides that prevents follicular rupture. A peripheral string-of-beads row of multiple, equal-sized follicles, usually found in an enlarged ovary with a dense central stroma, is pathognomonic for polycystic ovary syndrome. 15

Imaging signs Simple functional and benign ovarian cysts have contents of fluid attenuation, have a smooth and thin cyst wall, and display posterior acoustic enhancement on ultrasound. They do not show wall thickening, internal septa, or solid components. The cyst contents may show higher echogenicity, increased signal intensity, or increased attenuation due to proteinaceous material or intracystic hemorrhage. A corpus luteum cyst usually has a thick, irregular wall, is often hemorrhagic, and shows intense contrast enhancement, which can make it difficult to distinguish from a malignant process 15, 33 (▶ Fig. 12.10).

Caution

If a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst is suspected, a sonographic follow-up should be scheduled 6 weeks after the initial examination (an acyclic schedule, therefore subject to a different hormone status). Alternatively, MRI should be performed for further differentiation. 33

Clinical features Functional and benign ovarian cysts are usually asymptomatic and have a strong tendency to regress over time. On reaching a certain size, however, they may cause dull, diffuse lower abdominal pain by exerting pressure on adjacent organs. They may also cause bladder and bowel dysfunction and back pain. Sudden, excruciating pain with possible nausea and vomiting may signify a ruptured cyst or twisted pedicle. 17

Differential diagnosis 34

Cystadenoma.

Endometrioma (hyperintense in unenhanced T1W sequences, hypointense in T2W sequences).

Cystadenocarcinoma (check for malignancy criteria).

Pitfalls Follicles at different stages of maturity, sometimes coexisting with functional or benign ovarian cysts, are a common finding in women of reproductive age. This normal pattern should not be erroneously described as a “polycystic ovary” (▶ Fig. 12.11).

Fig. 12.13 Multiple follicles. Both ovaries contain multiple follicles of varying size and maturity in a young woman not taking hormonal contraceptives. Physiologic amounts of free fluid are visible in the lesser pelvis.

Ovarian and Tubal Torsion

Brief definition Twisting of the ovary on its vascular pedicle may result from abrupt body movements in a patient with a large ovarian cyst or tumor. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube is extremely rare (1:1.5 million). Risk factors are a long mesosalpinx, hydrosalpinx, acute pelvic inflammatory disease, hypermotility of the fallopian tube, or trauma. The incidence is highest in women of reproductive age, but children may also be affected. Adnexal torsion more commonly occurs on the right side. This could relate to a hypermobile ileocecal pole on the right side, or the fact that the left half of the pelvic cavity is mostly occupied by the sigmoid colon, leaving little room for tubo-ovarian torsion to occur. 23, 28, 35, 36

Imaging signs

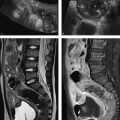

Ovarian torsion: The ovary may show edematous swelling and wall thickening. The fallopian tube may also be thickened, and follicles may be arranged in a ringlike pattern at the periphery of the twisted ovary. Ascites is often detectable. Ovarian torsion is confirmed by an absence of flow signals on Doppler ultrasound (▶ Fig. 12.12) or absence of enhancement on sectional imaging after IV administration of contrast medium. Frequently the uterus is tilted toward the side of the torsion. 15, 18, 37

Fig. 12.14 Ovarian torsion in an 8-year-old girl. Ultrasound scan shows an enlarged ovary ([a], arrow) bordered by free fluid ([a], open arrow). Normal Doppler signals are almost completely absent in the twisted pedicle (b). T2W images show enlargement of the affected right ovary ([c], [d], arrows). The follicles are arranged in a ring pattern at the periphery of the ovary. The left ovary appears normal ([c], [d], open arrows). In the contrast-enhanced T1W GRE images, the affected ovary is markedly enlarged (e) and shows less enhancement than the left ovary (f). (a) Ultrasound. (b) Color Doppler ultrasound. (c) Axial T2W image without fat suppression. (d) Coronal T2W image with fat suppression. (e) Sagittal T1W GRE image after IV administration of contrast medium. Right ovary. (f) Sagittal T1W GRE image after IV administration of contrast medium. Left ovary. B, bladder.

Fig. 12.15

Tubal torsion: The fallopian tube is dilated and its wall may be thickened. The ipsilateral ovary may appear normal. It is common to find ascites and a perifocal inflammatory reaction. 38

Clinical features The classic clinical presentation of acute torsion is severe unilateral pain of sudden onset, muscular guarding, possible nausea and vomiting, and possible laboratory signs of inflammation. Patients with gradual torsion present with lower abdominal pain, possible guarding, fever, nausea, and vomiting. Torsion of the pedicle initially leads to hemorrhagic infarction (due to venous stasis). Additional involvement of the arteries may lead to ovarian necrosis with hemorrhage and shock, sometimes accompanied by paralytic ileus. The pain resulting from tubal torsion may radiate to the groin or thigh. 15, 17, 28, 39

Differential diagnosis 28

Ruptured ovarian cyst.

Tubo-ovarian abscess.

Hydrosalpinx.

Acute abdomen from a different cause.

Polyps

Brief definition Polyps of the uterine corpus or cervix are common incidental findings. They may be sessile or they may protrude into the lumen attached to the mucosa by a pedicle. They may be hypertrophic, atrophic, or functional. The risk of endometrial cancer is increased 9-fold in patients with endometrial or cervical polyps. 31

Imaging signs Polyps appear sonographically as hyperechoic masses. On MRI they are iso- to hypointense to endometrium in unenhanced T2W sequences. After IV administration of contrast medium, small polyps show higher signal intensity (due to greater enhancement) than large polyps. 40

Clinical features Patients may complain of hypermenorrhea (increased bleeding due to decreased uterine contractility), menorrhagia (bleeding for more than 6 days), or metrorrhagia (acyclic bleeding, depending on the size of the endometrial polyp. Polyps may also cause postmenopausal bleeding. The torsion of a pedunculated polyp may cause cramping, laborlike pains. Cervical polyps are usually asymptomatic. 31

Differential diagnosis

Leiomyomas.

Endometrial hyperplasia.

Endometrial carcinoma.

Cervical carcinoma.

Leiomyomas

Brief definition Leiomyomas (fibroids) are benign, estrogen-sensitive neoplasms derived from smooth muscle cells. More than 90% are located in the uterus. Approximately 25 to 35% of women of reproductive age have leiomyomas. New leiomyomas cease to form after menopause, and existing fibroids tend to regress. Leiomyomas have a pseudocapsule and smooth margins, and are classified by their location as submucosal (growth directed toward the lumen), intramural, or subserosal (growth directed outward). Pedunculated leiomyomas also occur. Besides the uterine cavity, fibroids may also occur at cervical, vaginal, and intraligamentous sites. 40

Imaging signs The diagnosis is usually based on pelvic examination and ultrasound, which depicts leiomyomas as rounded, heterogeneous masses with smooth margins. High-resolution pelvic MRI is useful for evaluating leiomyomas that are large or have increased in number, for planning treatment (especially embolization, ultrasound thermoablation, and MRI-guided ablation with focused ultrasound), and for the exclusion of a malignant process (▶ Fig. 12.13, ▶ Fig. 12.14). The MRI signal characteristics of leiomyomas vary with their composition 40:

Leiomyomas without degenerative changes: These are rounded, sharply circumscribed, fibrocyte-rich tumors that are slightly hypointense to myometrium in T1W sequences and very hypointense in T2W sequences. The signal pattern is usually inhomogeneous after IV administration of contrast medium, and a pseudocapsule can often be identified (see ▶ Fig. 12.13). 10

Leiomyomas with degenerative changes: These tumors tend to show heterogeneous signal intensity even in unenhanced sequences due to internal calcifications or the presence of hyaline, fatty, myxomatous, or liquid components (see ▶ Fig. 12.13).

Fig. 12.16 Localization of leiomyomas. (a) Sagittal T2W image displays three small, hypointense intramural leiomyomas and two large subserosal leiomyomas with degenerative changes in the posterior wall of the uterine corpus. The anteflexed uterus abuts the bladder roof. (b) Axial T2W image in a different patient shows a submucosal leiomyoma protruding into the uterine cavity. Both ovaries, which contain follicles and functional cysts, are visible on the pelvic wall.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree