6 Fibrocystic Change Around the age of 35, degenerative structural changes begin to develop in the glandular tissue of the breast. Involution, with replacement of parenchyma by fat, is accompanied variably by fibrous tissue proliferation, micro- and macrocyst formation, and adenosis. Fibrocystic change is so common that, in the absence of troublesome symptoms, it should not be referred to as “fibrocystic disease” as it once was, to the consternation of women who were denied medical insurance coverage because of a “pre-existing condition.” Although not always definitive, imaging plays an important role in helping to distinguish fibrocystic change from atypical or malignant lesions. Mammography and ultrasound are complementary. The heterogeneous conglomeration of conditions known as fibrocystic change has several synonyms: fibrocystic disease, diffuse benign breast disease, mastopathy. It is commonly associated with a cyclic pattern of recurring and remitting pain and with diffuse or circumscribed areas of breast firmness (Table 6.1). Generally there is no need for treatment, and most patients with fibrocystic changes can tolerate the symptoms when given appropriate reassurance. Treatment is occasionally warranted if pain is severe. If so, the specific causes should be ascertained (Tables 6.2, 6.3). Fibrosis may involve the entire breast or may be regional, with anatomic variations affecting, for example, the periductal tissues more than the interlobar tissues. As ducts narrow and become obliterated, an imbalance develops between secretion and reabsorption. Expanded by trapped secretions, some ducts may undergo cystic dilatation attributed to disturbances in menstrual regulation and to individual predisposing factors. Areas of firmness in a dense fibrous breast or palpable circumscribed masses can be difficult to interpret on physical examination. Fibrocystic change is detected histologically in approximately 50% of all women 40–50 years of age and in a smaller percentage of younger women. For biopsy specimens, the pathologist is charged with assigning not only a diagnosis of fibrocystic change but also with indicating the level of increased risk of breast cancer, if any. Frequently the fibrocystic change is a histologic mixture that might contain simple degenerative or fibrotic changes, epithelial proliferations in the ducts or lobules that can be graded as mild, florid, or atypical, the last a high risk marker most often managed with excision. These proliferative processes correspond respectively to benign breast disease grades I–III in the Prechtel classification (Table 6.4). The distinctions are important for the clinician as well, since grade I is not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. In women with grade II change, the relative risk of breast cancer is 2.5 times higher than in women of the same age without this risk factor. Grade III is associated with a 3–5-fold increase in the cancer risk. High relative risk is a significant factor that should be taken into account in managing the patient.

Clinical Significance

Manifestations | Features |

Tension | Unilateral or bilateral |

Feeling of heaviness | Circumscribed or diffuse |

Pain | Cyclic or noncyclic |

Firmness | Usually increases in the premenstrual period |

Nodularity | Cyclic or persistent |

|

– Increase in total levels |

– Increase in free estrogens |

|

– Luteal insufficiency |

– Anovulatory cycles |

|

– Pituitary |

– Pharmacologic |

|

– TSH ↑→ TRH ↑→ prolactin ↑ |

– Secondary luteal insufficiency |

Mild therapies | Hormonal therapies |

|

|

Diagnosis with Ultrasound

The criteria for the ultrasound diagnosis of fibrocystic change are shown in Table 6.5.

Common Findings

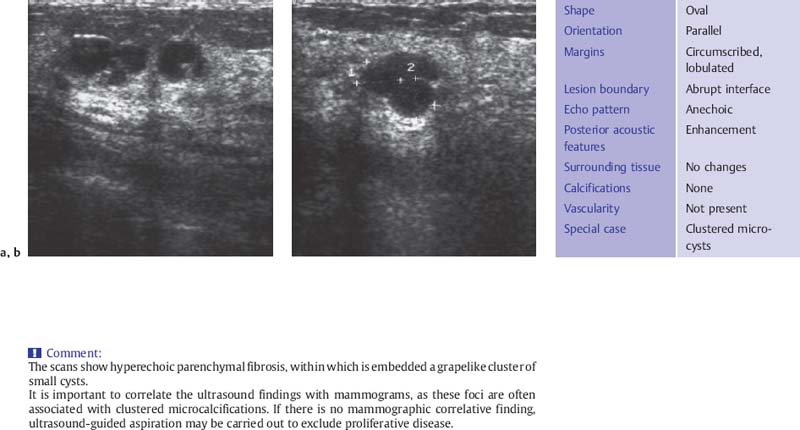

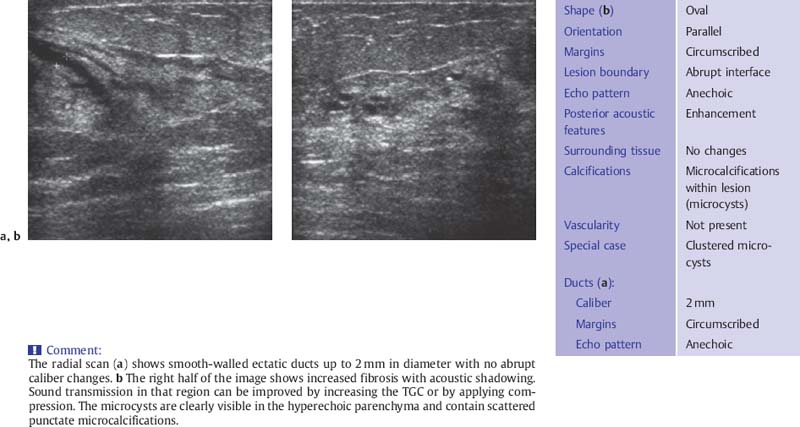

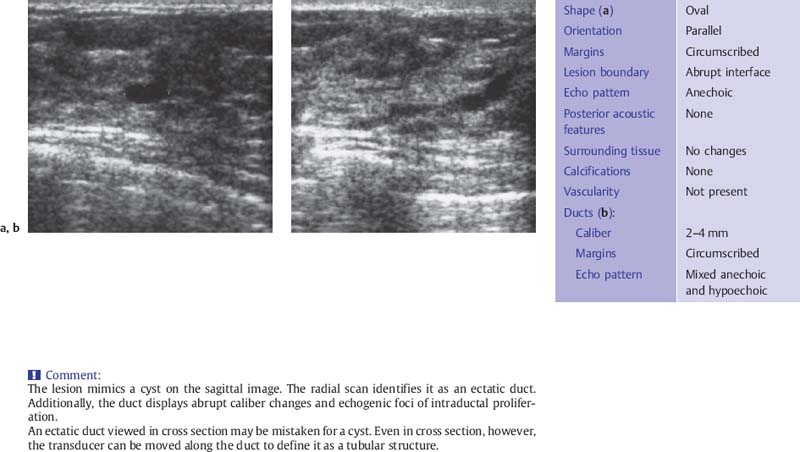

The fibrotic parenchyma appears hyperechoic, and its echotexture is coarser than that of normal glandular tissue (Fig. 6.1 a, b). The fibrosis increases the reflection and refraction of sound, leading to greater sound absorption. This can hamper the evaluation of large breasts because of poor image quality and acoustic shadowing at deeper levels, but compression and change in the patient’s position can be used in these cases to improve sound penetration and for better delineation of deeper structures. Changes such as duct dilatation are often found in the subareolar area, and particular care is required in evaluating this region (Fig. 6.2 a, b). Here, sliding the areolar skin to one side will diminish artifact and allow clear insonation of the area behind the nipple. High-resolution scanning will often reveal microcysts 0.5–2.0 mm in size, many of which cannot be detected with the type of equipment that is no longer recommended for breast scanning (Fig. 6.3 a, b). Aggregations of microcysts or macrocysts can be associated with proliferative forms of fibrocystic changes, often but not always with apocrine metaplasia (Fig. 6.4 a, b). Frequently ductal dilatation is associated (Figs. 6.5 a, b, 6.6 a, b).

A good-quality scanner used with a 10-MHz or higher transducer frequency will often define the lactiferous ducts as tubular structures converging toward the nipple (see Fig. 6.8).

Histologic grade | Proliferation | Relative cancer risk |

I | None | Not increased |

II | Proliferation without atypia | Risk factor of 2–2.5 |

III | Proliferation with atypia | Risk factor of 3–5 |

Shape, extent | Diffuse or oval lesions |

Orientation | Parallel |

Margin | Indistinct or circumscribed |

Lesion boundary | Abrupt interface |

Echo pattern | Hypoechoic or hyperechoic |

Posterior acoustic features | Shadowing |

Surrounding tissue | No changes, but fibrosis may limit readibility |

Calcifications | Microcalcifications may be present in mass |

Vascularity | Diffusely increased vascularity in (surrounding) tissue |

Ducts: Caliber Margins Echogenicity |

1–2mm Circumscribed Anechoic |

Fig. 6.1 a, b Sonographic and mammographic features of fibrotic change.

a Midsagittal ultrasound scan demonstrates the parenchymal cone, flanked by fat, which tapers anteriorly toward the nipple and thickens toward the periphery. A standoff pad was used to improve skin definition. Despite compression, the subareolar region appears hypoechoic and is obscured by acoustic shadows. Fibrous tissue proliferation coarsens the structure of the breast parenchyma and increases its echogenicity.

b The mammogram shows patchy areas of increased breast density (7.5-MHz transducer).

Fig. 6.2 a, b Midsagittal scan of the subareolar region in a breast with fibrotic change, noncompression and compression views.

a Intense shadowing centrally in the noncompression scan prevents evaluation of the parenchymal structure.

b Compression improves sound transmission so that the ducts and deeper glandular tissues can be seen. It is not totally effective, however, in compensating for the increased sound absorption due to fibrosis (10-MHz transducer).

Fig. 6.3 a, b Fibrocystic focus with microcysts 0.5 mm in diameter.

a High-resolution ultrasound scan (10-MHz transducer).

b Scan with a 5-MHz transducer.

Fig. 6.4 a, b Breast cysts aggregated in grape like pattern.

a Sagittal scan.

b Transverse scan (10-MHz transducer).

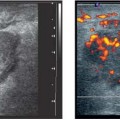

Fig. 6.5 a, b Fibrocystic change with microcysts and duct ectasia.

a Appearance of duct ectasia on a radial scan.

b Peripheral scan in the upper outer quadrant shows fibrotic changes in the parenchyma with an aggregation of several microcysts (10-MHz transducer).

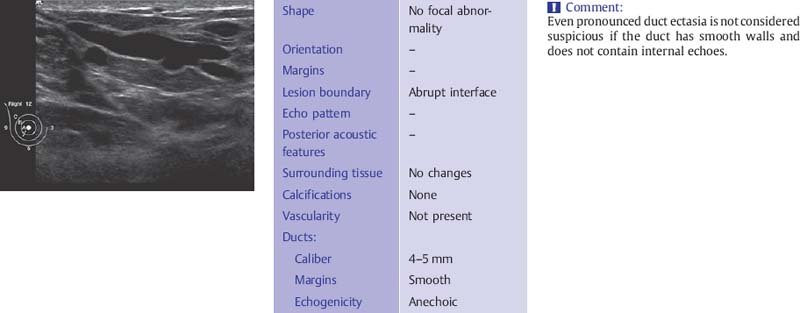

Fig. 6.6 a, b Duct ectasia.

a The ectatic duct resembles a cyst when imaged in cross section.

b A radial scan defines the course of the ectatic duct as it approaches the nipple. Adjoining the expanded, anechoic duct segment are hyperechoic, irregularly dilated segments that suggest intraductal proliferation. Histology: fibrocystic change without atypia (7.5-MHz transducer).

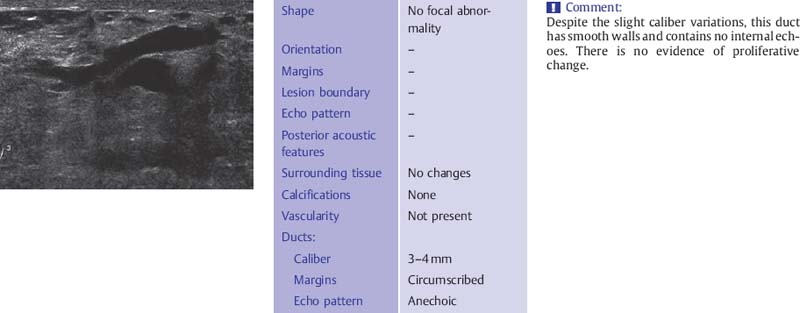

Fig. 6.7 Dilated, secretion-filled duct with smooth walls and slight caliber variations (12-MHz transducer).

The ducts have smooth borders and taper toward the periphery where they may be less than 1 mm in diameter. There is wide variability in what is considered to be normal ductal caliber (Fig. 6.7). In women with ovarian cycles and those receiving hormone replacement therapy the ducts contain anechoic secretions. As the breast involutes at menopause, the ducts collapse and are less conspicuous although ectatic ducts more than 3–4mm in diameter are not uncommon as a degenerative finding and are not suspicious for proliferative change if they have smooth walls and contain anechoic secretions (Fig. 6.8). These ducts may contain within them the thick, linear calcifications, commonly known as “secretory calcifications” and at times referred to as “plasma cell mastitis.” These calcifications have no clinical significance and are to be distinguished from the groups of linear, branching micro-calcifications linearly arrayed that may represent ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and require biopsy.

Fig. 6.8 Subareolar duct ectasia (12-MHz transducer).

Less Common Findings

The diagnostic criteria for less common forms of fibrocystic change are listed in Table 6.6.

Localized areas of fibrocystic change may present as hypoechoic focal lesions with indistinct margins and shadowing (Fig. 6.9 a, b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Estrogen stimulation

Estrogen stimulation Progesterone deficiency

Progesterone deficiency Prolactin stimulation

Prolactin stimulation Thyroid hormone and iodine deficiency

Thyroid hormone and iodine deficiency Withdrawal of methylxanthines (coffee, tea)

Withdrawal of methylxanthines (coffee, tea) Low-fat diet

Low-fat diet Evening primrose oil

Evening primrose oil Phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens Diuretics

Diuretics Cold compresses

Cold compresses Local progesterone gel

Local progesterone gel Acupuncture

Acupuncture Estrogen reduction

Estrogen reduction Progestin (cyclic)

Progestin (cyclic) Danazol

Danazol Dopamine agonists

Dopamine agonists Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen GnRH analogs

GnRH analogs Thyroid hormones

Thyroid hormones