Foreign Body Aspiration

Alexander M. Kowal

Etiology and Epidemiology.

Ingestions occur frequently with children and mentally handicapped adults. Foreign body aspiration represents 7% of lethal accidents in infants between 1 and 3 years. The mean age at presentation is 2 years with 98% of cases younger than 5 years. Boys outnumber girls 2:1. Younger children have smaller caliber airways and immature protective mechanisms, increasing the risk of morbidity and mortality. Careful medical history is the key to early diagnosis, but only 19-33% of events are witnessed and children may not volunteer the correct history. The correct diagnosis is only made within 24 hours of presentation in 59% of cases. Although negative imaging does not exclude foreign body aspiration, imaging is helpful when history is uncertain and the presentation is late. Complication rates greater than 95% have been observed with delays in diagnosis over 30 days, including pneumonia, lung abscess, granuloma, and bronchiectasis. Foreign body aspiration is rare in adults and associated with alcohol intoxication, traumatic intubation, psychosis, neurologic disorders with impaired swallow function, seizures, and dental procedures.

Symptoms and signs depend on the size, location, duration, and composition of the foreign body. The classic triad of cough, wheezing, and unilateral decreased breath sounds is present in 30-60% of cases of lobar bronchial foreign body aspiration. The most common presentation is choking followed by intractable coughing (72%). Other symptoms include prolonged, paroxysmal cough, dyspnea, recurrent pneumonia and fever, cyanosis, and intermittent hemoptysis. Laryngotracheal foreign bodies are more likely to be symptomatic and are commonly associated with apneic episodes, biphasic stridor, and hoarseness/dysphonia/aphonia. Symptoms may often subside spontaneously to a relatively asymptomatic state. Physical examination will be abnormal in 80% of cases. Symptoms include decreased unilateral air entry. Unilateral wheezing (60%) in the absence of prior pulmonary disease is highly suspicious for foreign body.

Differential diagnosis for the symptoms of foreign body aspiration include viral infection such as croup, asthma, cystic fibrosis, gastroesophageal (GE) reflux, mucus plugs, pneumonia, left to right shunt (“cardiac asthma”), hydrocarbon ingestion, allergic reactions, mediastinal tumors/adenopathy, and congenital/developmental anomalies such as tracheoesophageal fistula.

Location of Foreign Bodies.

In general, the younger the age of the child, the higher the involved anatomic site. Approximately 60% lodge in the main stem bronchi and 35% in segmental bronchi. Although most cases are unilateral, there is no statistically significant difference when comparing the left and right main bronchus in children aged 1-3 years due to an equal angle of bifurcation. In adults, foreign bodies occur more often in the right bronchus, especially the bronchus intermedius. Foreign bodies can also lodge in the larynx (6-9%), trachea (5-17%), or esophagus.

Composition of Foreign Bodies.

Most aspirated foreign bodies are foods (70%), especially peanuts (59%), sunflower seeds, popcorn, and hotdog fragments; therefore, most are radiolucent. In addition to causing obstruction, a foreign body will also elicit a local inflammatory response whose severity is dependent on the composition of the object. The most severe inflammation results from the oil content of vegetable substances, such as

peanuts, which increase local swelling further impeding airflow. In adults, the most common foreign bodies include aspirated denture and tooth fragments, animal bones, and tablets.

peanuts, which increase local swelling further impeding airflow. In adults, the most common foreign bodies include aspirated denture and tooth fragments, animal bones, and tablets.

Valve Mechanisms.

The more proximal elastic airway tends to expand and permit air flow past the foreign body during inspiration, but the elasticity impedes air flow during expiration. This results in air trapping distal to the foreign body by a check valve mechanism. Reflex oligemia due to hypoventilation will also occur. If the object migrates more distally, complete obstruction with distal atelectasis occurs by a stop valve mechanism. The latter mechanism is less frequent, occurring in 10-25% of lobar foreign body aspirations.

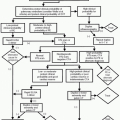

Indications.

Radiographs should be used in the initial evaluation of all patients with suspected foreign body aspiration or chronic pulmonary symptoms. In 10-24% of cases, the foreign material is radiopaque and no further radiologic workup is necessary. Opaque foreign bodies may include metals, glass, and most animal bones. If radiolucent, indirect radiologic signs such as obstructive emphysema (44-64%) must be sought and other imaging modalities considered. Radiolucent foreign bodies can include aluminum, fish bones, plastic, wood, and vegetable products. Chest radiographs have 60-68% sensitivity and 37-71% specificity. A normal chest radiograph is present in 9-35% of cases.

Protocol.

Routine posteroanterior (PA) (inspiratory) and lateral views for cooperative children. Routine anteroposterior (AP) and cross-table lateral views for younger children. Other views: expiratory, lateral decubitus. Soft tissue AP and lateral views of the neck to identify upper airway foreign bodies.

Imaging Tips.

In infants and young children, obtaining an expiratory film may be very difficult. “Assisted expiratory” chest radiograph may be helpful in these instances. At the end of child’s expiration, vigorous pressure is applied to the epigastrium, forcing diaphragm upward.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree