Key Points

- •

Image acquisition of the gallbladder can be challenging due to variability of gallbladder shape, size, and position.

- •

Point-of-care ultrasound can detect gallstones, a thickened gallbladder wall, pericholecystic fluid, and a sonographic Murphy’s sign to assist in diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

- •

A complete biliary ultrasound exam includes measurement of the common bile duct diameter.

Background

Gallbladder disease is a concern for health care providers around the world. Disease severity ranges from asymptomatic cholelithiasis to acute cholecystitis to ascending cholangitis. Point-of-care ultrasonography is a valuable tool for evaluating patients with right upper quadrant abdominal pain suspicious for gallbladder disease. Advantages of point-of-care ultrasound include avoidance of ionizing radiation, rapid performance, availability in many clinical settings, high sensitivity and specificity for gallbladder disease, and potential reduction in length of stay and cost savings.

Several studies have shown that diagnostic accuracy is not compromised when a focused gallbladder ultrasound exam is performed by a nonradiologist compared to a comprehensive gallbladder ultrasound exam performed in a radiology suite. A recent systematic review found that emergency physician (EP)–performed ultrasound for symptomatic cholelithiasis had a sensitivity of 89.8% and a specificity of 88.0%. Furthermore, training of novices to perform limited, point-of-care gallbladder ultrasound exam has been shown to have a steep learning curve with competence attainable without requiring extensive training.

The most important positive findings when performing a point-of-care gallbladder and biliary ultrasound exam are:

- ▪

Cholelithiasis

- ▪

Sonographic Murphy’s sign

- ▪

Gallbladder wall thickening

- ▪

Pericholecystic fluid

- ▪

Common bile duct (CBD) dilation

The presence or absence of gallstones is the first and most important ultrasound finding. Acalculous cholecystitis is uncommon overall but should be considered in hospitalized patients with critical illness. Sonographic Murphy’s sign, gallbladder wall thickening, and pericholecystic fluid are all ultrasound features of acute cholecystitis and are generally easy to evaluate with point-of-care ultrasonography. Common bile duct (CBD) assessment is technically the most difficult and time-consuming part of the exam. The utility of obtaining CBD measurements when performing point-of-care biliary ultrasound has been called into question recently. One retrospective review of 125 pathology-confirmed cases of cholecystitis that had a radiology-performed ultrasound revealed that all instances of CBD dilation were accompanied by one or more additional findings: positive sonographic Murphy’s sign, gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, or laboratory abnormalities. This review would suggest that CBD visualization confers no additional sensitivity to the point-of-care diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

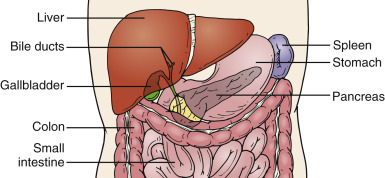

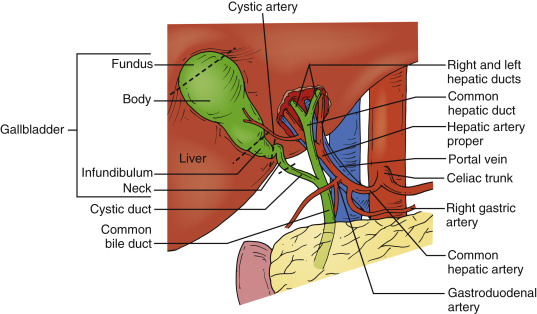

Normal Anatomy

The gallbladder is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen along the posterior, inferior edge of the liver ( Figure 19.1 ). It is pear-shaped and lies along the main lobar fissure between the right and left lobes of the liver. The fundus of the gallbladder is usually the most anterior and inferior structure and is often the first part of the gallbladder visualized with ultrasound. The fundus is continuous with the body and neck that tapers cranially and posteriorly to form the cystic duct ( Figure 19.2 ). The cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct from the liver to form the common bile duct. The cystic duct is frequently not visualized with ultrasound and therefore the extrahepatic ductal system is often referred to as common bile duct. The common bile duct continues to the head of the pancreas, where it enters the duodenum through the sphincter of Oddi.

Image Acquisition

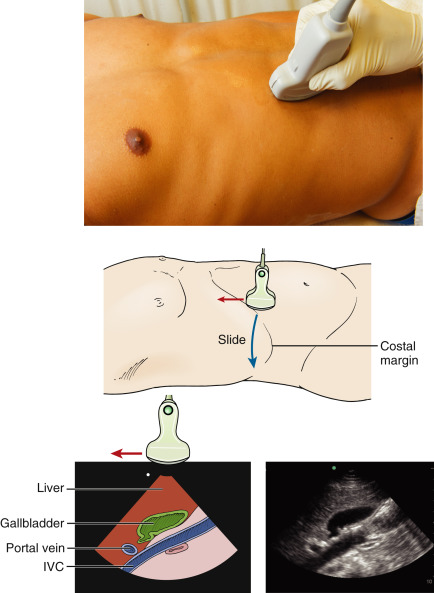

Patients are generally in a supine position for most point-of-care ultrasound scanning, including the gallbladder exam. Certain maneuvers when positioning conscious and cooperative patients can help optimize gallbladder visualization. Instructing the patient to take and hold a deep breath often transiently descends the gallbladder inferiorly into the field of view. Also, turning the patient into a left lateral decubitus position shifts gas-filled loops of small bowel, and may enhance gallbladder visualization.

A curvilinear abdominal transducer (2.5–5 MHz frequency) is typically used to image the gallbladder. A phased-array transducer may be used as well, because its narrower footprint is ideal for imaging through rib spaces. As with all ultrasound scanning, lower frequencies allow deeper penetration into the body, but lower frequencies also have lower resolution. Using the highest possible frequency that provides adequate penetration will maximize resolution when assessing for signs of gallbladder disease.

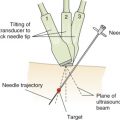

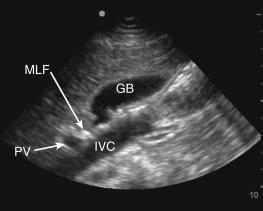

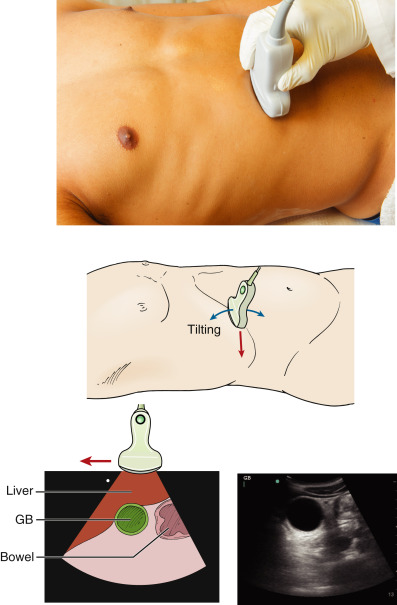

Start by placing the transducer along the inferior border of the costal margin on the patient’s right side with the transducer marker pointing toward the patient’s head. Rock the transducer slightly cephalad ( Figure 19.3 ). Next, slide the transducer laterally and inferiorly along the costal margin until the gallbladder comes into view. The gallbladder will appear as a hypoechoic oblong or circular structure. Rotate and tilt the transducer with fine movements until the gallbladder is seen along its true long axis. In a longitudinal plane (long-axis view), the relationship between the thick-walled portal vein and gallbladder is often viewed as an “exclamation point” with the hyperechoic main lobar fissure connecting the two structures ( Figure 19.4 ).

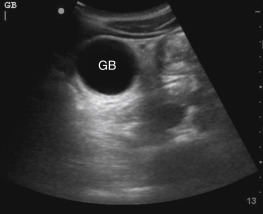

The gallbladder should also be viewed in a transverse orientation (short-axis view) by rotating the transducer 90 degrees counterclockwise from a longitudinal orientation with the transducer marker pointing to the patient’s right ( Figure 19.5 ). Viewed in a transverse orientation, the gallbladder has a circular shape ( Figure 19.6 ). It is important to sweep through the entire gallbladder in both transverse and longitudinal planes to ensure complete visualization.

The gallbladder may also be visualized between the ribs of the right anteroinferior chest wall when it is difficult to visualize the gallbladder as previously described. The narrower footprint of a phased-array transducer may be preferred for intercostal imaging to minimize rib shadows. Further, placing the transducer on the right lateral chest wall, in the mid-axillary line, may be attempted. From the lateral chest wall, move the transducer medially between ribs to visualize the gallbladder in different planes. One limitation of intercostal imaging of the gallbladder is the inability to assess for a sonographic Murphy’s sign.

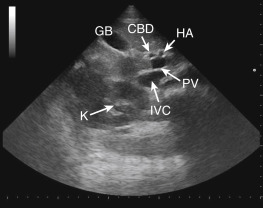

Measuring CBD diameter is the most challenging and time-consuming aspect of a point-of-care biliary ultrasound exam. Additionally, it requires significant training and practice to become proficient. Although its value in diagnosing acute cholecystitis has been challenged, providers usually obtain CBD measurements when performing a biliary ultrasound exam. Viewing the gallbladder in a longitudinal plane is helpful when locating and measuring the CBD because the CBD is located just anterior to the portal vein. The porta hepatis is the area containing the portal vein, CBD, and hepatic artery and is commonly called the “Mickey Mouse” sign ( Figure 19.7 ). The inside diameter of the CBD is measured in either a transverse or longitudinal plane at the point where the hepatic artery courses between the portal vein and CBD ( Figure 19.8 ). Color flow or power Doppler can be used to help distinguish the CBD from the portal vein and hepatic artery ( Figure 19.8 ).